Neutrality in the public education system: does it exist?

Politicians are trying to pass a bill to avoid what they call ideological indoctrination in Brazilian public schools. Such discourse hides a strong religious orientation and threatens the development of the critical thinking necessary for democracy.

The comparison between Che Guevara, a Cuban revolutionary leader, and Francis of Assisi, one of the most popular Catholic saints, made by his daughter’s teacher during class was the final straw for the Catholic Brazilian lawyer Miguel Nagib. He started a mobilisation that became known as “Escola Sem Partido”, which means “schools without political parties” or “without political positioning”. According to Nagib, students of public schools have been victims of political and ideological indoctrination by teachers, who “take advantage of the students’ captive audience to promote their own interests”.

Nagib defends that the compulsory exposure to content that may be in conflict with the moral beliefs of students or their parents violates the American Convention on Human Rights, according to which “parents or guardians, as the case may be, have the right to provide for the religious and moral education of their children or wards that is in accord with their own convictions”.

One of the arguments listed on the official website to justify the movement states that “under the pretext of ‘building a fairer society’ or ‘fighting against prejudice’, teachers at all levels have been using the precious time of their classes to convince students on issues of a political, partisan, ideological and moral nature”.

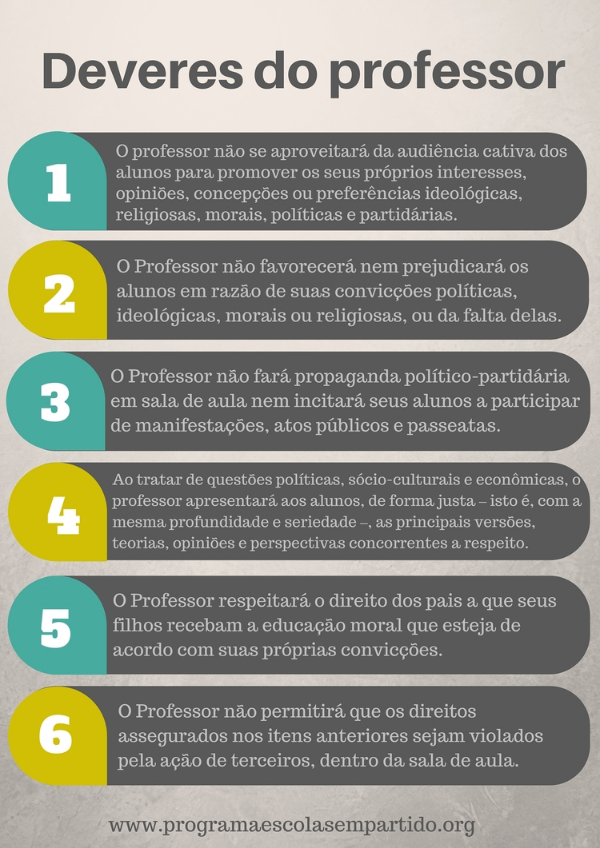

Poster created by the movement "Escola Sem Partido" with the obligations of the teachers, which must be exposed in the schools of the cities where the law were approved.

The lawyer explains by using two examples: “a Marxist and therefore atheist teacher who can expose his worldview (…) to students whose families practice a religion and believe in God; and (…) teachers who during sex education classes tell students that ‘there is no problem with sex, with pornography and that masturbation is part of sexuality’, which can cause the young person to have ‘an active sex life (…) and girls to get pregnant, making parents to ‘carry the can’” (El País, 2016).

Movement gained popularity with the bill in Rio de Janeiro

The episode mentioned above took place in 2003, but the movement “Escola Sem Partido” became popular and more widely discussed in 2014, when it turned into the bill 2974, authored by state congressman Flavio Bolsonaro, to be studied and voted for or against by the Legislative Assembly of the State of Rio de Janeiro. Since then, the movement has provided bill models to be adopted by both state and municipal spheres. At the national level, similar projects are being carried out both in the Chamber of Deputies, authored by the federal congressman Erivelton Santana in 2014, and in the Senate, authored by senator Magno Malta in 2016 (Agência Brasil, 2017).

The politicians behind the bills

Flavio Bolsonaro was elected in 2014 for his fourth mandate as congressman at the Legislative Assembly of the State of Rio de Janeiro. Bolsonaro, whose father and brothers are also known as evangelical and right-wing politicians, was candidate for mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro in 2016.

Erivelton Santana was councilman of Salvador, the capital of the State of Bahia, in northeastern Brazil, and currently is federal congressman in the Chamber of Deputies, a position he has held since 2011. In his biography, published on his official blog, the politician assumes he has been elected to represent the evangelical segment of the population.

Magno Malta was a federal congressman in 1999 and is senator since 2003. In his biography, published on the Senate’s official website, his profession is listed as evangelical reverend.

Santana and Malta are members of the Evangelical Parliamentary Front, composed of senators and federal congressmen. The bill 6583, also known as the Family Statute, is among the policies supported by the group.

The Family Statute defines “a familial entity as the social nucleus formed from the union between a man and a woman”, excluding other types of family structure. Diego Garcia, rapporteur of the Chamber of Deputies’ Special Committee created to analyse bill 6583, affirms in his report (published in September 2015) that its article 9 intends to guarantee religious and moral education according to students' and their parents' convictions. “The right assured by article 12 of American Convention on Human Rights is exclusive: it cannot be exercised by third parties without express delegation of the holder (of the custody of the student)”.

During the meeting in which the rapporteur's assessment on the Family Statute was voted, a militant holds a sign with the words: "the bill 6583 wants to justify hatred and legitimate prejudice".

Counterarguments

The attempt of politicians to officialise the movement “Escola Sem Partido” generated strong reactions, mainly among educators, labour unions, student entities, social movements, and left-wing parties and politicians. They launched a manifest in July 2016, in which they declared: “Defending school without political parties is to defend school with only one political party; the political party of those against secular education, and against the debate on gender, strengthening rape culture and LGBT-phobia in our country. We defend a critical school, liberating education, plurality of ideas and freedom of expression and thought”.

During a public hearing in March 2017 at the Chamber of Deputies, critics argued that the bill will produce “an insecurity scenario for teachers, who do not know clearly what is considered indoctrination and, thus, becoming subject to persecution” (Agência Brasil, 2017). The reverend Romi Benke, secretary general of the National Council of Christian Churches of Brazil, who was present at the public hearing, claimed that the bill can intensify social inequality by censoring issues such as agrarian concentration and violence against women, causing them not to be debated in classrooms. These topics can be interpreted by students and their parents as political positions (Agência Brasil, 2017).

Even the founder of the movement, Miguel Nagib, agreed that there is a loophole in this bill that allows religious beliefs to be imposed upon science: “The way the article is written, any content in conflict with parents’ religious or moral convictions could be forbidden, including scientific content, which is unacceptable”. He predicts, for instance, teachers being penalised for teaching the theory of evolution, because it diverges from creationism (Agência Brasil, 2017).

“The school does not exist if separated from society”

Renata Aquino, member of the movement “Professores Contra o Escola Sem Partido”, which means “teachers against schools without political parties”, explained to El País (2016) that representatives of “Escola Sem Partido” think that “the school is trying to impose a worldview and violate what students learn in private space (…). They do not want homosexual family or transsexuals to appear in school. (For them) [t]he school has to find a way to have education without mentioning all this diversity that exists in our society. But the school does not exist if separated from society”.

Is the idea of school without political positioning a fallacy?

It is evident that the “Escola Sem Partido” movement has a strong religious ideology supporting it and, instead of generating neutrality, it will provoke just the opposite. However, the belief that school is a naturally neutral environment, and that the teacher is responsible for unbalancing it, is dishonest, or at least naive.

The educational system in practice in Brazil and in many other Western industrialised countries is saturated with neo-liberal ideology, reinforced after the economic crisis in the nineteen-seventies and early eighties. In their book “Neo-liberalism, globalization and human capital learning: reclaiming education for democratic citizenship”, Hyslop-Margison and Sears (2006, p.5) explain that “[t]he welfare state policies of the 1960s and 70s were counterproductive to corporate interests because they interfered with the raw supply and demand labour market principles that form the foundation of unregulated capitalism.”

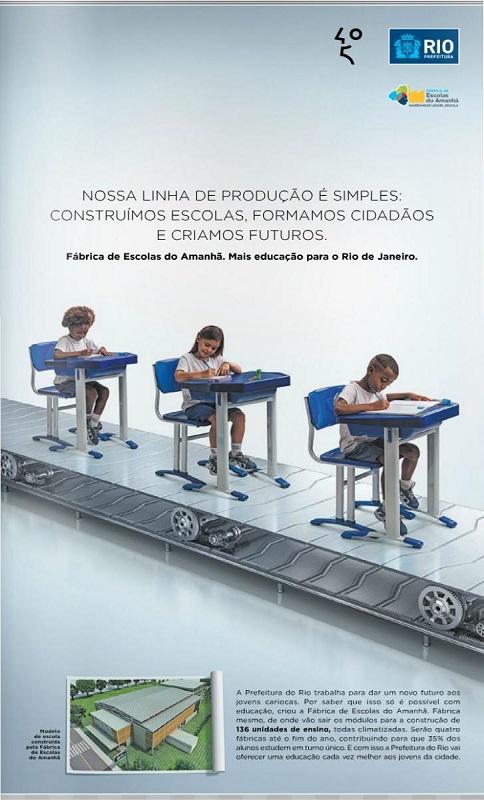

Advertisement of Rio de Janeiro City Hall published in newspaper of great circulation in 2014 with the sentence "our production line is simple". It was compared to the education system portrayed in Pink Floyd's Another Brick in the Wall music video.

In response to this situation, corporations invested in electing politicians with market-oriented proposals. Thus, the role of governments changed to fit in this new political and economic context. “The role (…) became that of creating optimum conditions for the practice of global economics in a social order totally committed to the logic of the marketplace. This (…) influenced environmental spending, social programs and the focus of public education.” (Hyslop-Margison & Sears, 2006, p.8-9)

This ideology, based on a discourse of naturalness that does not exist, is reflected in the school’s goals and curricula, which started focusing exclusively on preparing students to occupy a position in the competitive labour market, their “unquestionable, inevitable fate”. “Students are increasingly portrayed as submissive, or at least passive, objects being prepared simply to play out their role in the burgeoning global economy.” (Hyslop-Margison & Sears, 2006, p.14)

“Students are increasingly portrayed as submissive, or at least passive, objects being prepared simply to play out their role in the burgeoning global economy”

This concept of the students’ role expected by society was defined as an “insult” by the 16-year-old student Ana Julia Ribeiro in the speech she adressed to legislators, during a session at the Commission for Human Rights in the Brazilian Senate in November 2016. She was one of many students who occupied their public schools last year, in protest against the government’s plans to freeze education funding for 20 years. “Popularly known as “Gag Law”, the “Escola Sem Partido” (…) is [the same as] telling us, young people, the society, that they want to form an army of non-thinkers (…). The “Escola Sem Partido” insults and humiliates us. It tells us that we are not able to think for ourselves. But we are and we will not keep our heads down for this”, she said.

Education for critical thinking

The Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire introduced the pedagogy for freedom in his work with illiterate adults in the 1960s Brazil. After the coup d’etat in 1964, Freire was imprisoned and exiled by the military regime, which accused his teachings of containing “subversive elements”. What was considered subversive was, in fact, a method of educating that stimulated people to question things more, a real risk for any ideology in power.

According to Freire, in his book “Education: The practice of freedom” (2011, 14th edition), the current education system intends to keep the population in passive and naïve positions when they need to reflect on, and make decisions on, issues regarding their lives.

“Little, or almost nothing, (…) leads us to more searching, more restless, more creative positions. Everything, or almost everything, leads us (…) to passivity, to memorised knowledge only, which, not requiring us to elaborate or re-elaborate, leaves us in a position of inauthentic wisdom.” (Freire, 2011, p.126). The education system based on imposition instead of dialogue forms a barrier for criticality, which is “fundamental for democratic mentality” (Freire, 2011, p.126).

According to Paulo Freire, the current education system leads people to passivity.

The idea of neutrality in the public education system hides an ideology that wishes to perpetuate itself in power and that is “bought” by the population, increasingly naive and passive as a result of this uncritical education. This discourse ends up serving to promote pseudo-democratic projects such as the “Escola Sem Partido”, which, under the argument of religious freedom of expression, tries to stifle necessary debates for social inclusion and the exercise of true democracy.