APESHIT: The Carters versus Globalization and Art

With the APESHIT music video, The Carters took control of a high-cultural, worldwide-known art institution and turned it into a black excellence celebratory. But what are the specific claims the music video of APESHIT makes about globalization and art? And how do these claims disrupt the Western narrative of art?

APESHIT: The Music Video

APESHIT is a trap song composed by the musical duo The Carters. The Carters is a collaboration between American artists Beyoncé and Jay Z. The music video of APESHIT is the first visual from The Carters' album Everything Is Love. The song as well as the music video released in 2018.

The music video received eight nominations at the MTV Video Music Awards in 2019 and a nomination for Best Music Video at the 61st Grammy Awards. Rolling Stone named the music video the 29th greatest music video of all time (Brownie, et al., 2021).

For those who would like to watch one of the most iconic pop cultural music videos, you can do so here.

The APESHIT music video is directed by Ricky Saiz and produced by Iconoclast. It lasts six minutes and five seconds. The video opens with a man who has wings, crouching in front of a building. There can be sirens heard in the background. The camera then shows ceiling details of the Apollo Gallery at the Louvre museum. This is one of the most grandeur galleries of the museum. Eventually, the camera moves to The Carters posing in front of the ‘Mona Lisa’ by Leonardo Da Vinci. One of the most famous artworks in the entire world. But it is not just the 'Mona Lisa' which gets highly criticized. Famous artworks like ‘The Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon and the Coronation of Empress Joséphine’ and ‘The Intervention of the Sabine Women’ by Jacques-Louis David are shown in the music video.

APESHIT: The Embodied Meaning

In the music video of APESHIT The Carters take over the Louvre. The world’s most-visited art museum with a wide range collection from ancient civilizations to the 19th century. The expressed critique of APESHIT is on the collection of the Louvre, which predominantly features the work of white artists. Little of the exhibited artworks include people of colour in positions of power, as they were deemed not worthy subjects of cultural works (Grady, 2018). This is not uncommon for most Western Art museums. But, the criticism is not just about the Louvre as an institution. Nor about the representation of the Louvre regarding the monopolization of art by the Western narrative. It is also about the individual artworks, which are highlighted in the music video. These artworks are as well being criticized by the Carters and play a major role in APESHIT.

The selected artworks that are shown are criticized in various ways. Most importantly by minimizing the importance of the artworks. In one of the first shots of the music video, The Carters are positioned before the 'Mona Lisa', commanding attention and using the painting as a mere accessory. The Carters demand the attention of the viewer on several occasions in the music video. All artworks shown in the music video are reinterpreted by The Carters or the dancers. There is a distinct contrast visualized between the artwork and the women of colour positioned in front of it. APESHIT displays how a few synchronized dance moves can upstage the selected artworks. Again, these artworks are some of Western art’s most famous artworks.

Additionally APESHIT strategically highlights non-white artworks in the Louvre as well. Throughout the music video, there are brief glimpses of people of colour in famous paintings like ‘The Wedding at Cana’ by Paola Veronese. The camera singles out faces of colour.

The APESHIT music video is an embodied criticism of the Western domination of Art and disrupts the associated Western narrative.

The Carters in front of 'The Venus de Milo'.

APESHIT: Globalization and Art

As stated before the music video of APESHIT criticizes the domination of art by the West and disrupts the Western narrative of art. To understand the criticism behind the music video, the video is analysed through the lens of globalization.

According to Jan Nederveen Pieterse (2020), there are three paradigms that can be used when discussing globalization. These paradigms reflect different perspectives of cultural differences. One of these perspectives is the thesis of cultural convergence and worldwide standardization: the perspective of McDonaldization. It is the concept of homogenization of societies worldwide (Nederveen Pieterse, 2020). Specific to the APESHIT music video, the monopolization of art and the narrative of art by the West.

APESHIT emphasizes the dominance of the West and the master narrative it has in the history of art. It highlights the exclusion of non-Western countries in this master narrative. The artworks displayed in the APESHIT music video show how the most beloved artworks in the Louvre are artworks by white artists with white subjects.

The exclusion of art in the art industry is not an archaic concept. According to Belting (2009), world art is an old concept based on modernism’s universalism. Belting (2009) states that the modernist form of art had two thresholds to keep the concept of modernism clear. The first threshold constituted the synonymity between the making of art and the making of modern art. Artists who didn’t follow this principle were excluded from the art category. The second threshold constituted that only Western artists were accepted. This meant that those who did make modern art but lived outside the West were not included in the catalogue of art history (Belting, 2009). These two thresholds of modernist art imply that art is mainly Western and the narrative doesn’t represent the majority of countries.

It is safe to say that APESHIT agrees with Belting’s statements about the global cultural standardization by the Western World.

APESHIT: Globalization and Colonialism

Furthermore, the music video doesn’t just focus on the perspective of McDonaldization. It also displays the interconnectedness between globalization and colonialism. The music video uses the concept of travelling concept, meaning there is an intersubjectivity between globalization and colonialism. One cannot look at one concept without regard for another concept (Bal, 2009). In the case of the music video, one of the last shots of APESHIT ends with the ‘Portrait D’Une Négresse’ by Marie-Guillemine Benoist. This is the only artwork that is not upstaged or reinterpreted by The Carters or the dancers. The artwork is displayed as the only artwork in the music video that doesn’t need to be remade or re-examined. ‘Portrait D’Une Négresse’ is the sole artwork that is shown in the video in which a person of colour is the aesthetic object as well as the subject of an artwork (Grady, 2018).

APESHIT highlights the cruelty towards Black people during colonialism. The music video emphasises the traces of colonialism and slavery in these famous artworks. Throughout APESHIT the Carters or the dancers or both are placed in direct alignment with the artworks. Stating that they are just as worthy of being there as the artworks which are already exhibited at the Louvre. This statement is aimed at the gatekeepers of the narrative of art and the history of art (Gemmill, 2018).

Even though the artworks are of essence for the context of the music video, there is almost a feeling of disregard or even boredom for these artworks. These artworks are some of the most famous, worldwide known artworks, yet the display of mimicking and upstaging command the attention of the viewers. A treatment the artworks usually get. A treatment of importance and value. A treatment which is historically not given to black culture.

‘Portrait D’Une Négresse’ by Marie-Guillemine Benoist.

APESHIT: The Louvre

Using the Louvre as their location adds another dimension to APESHIT since The Carters not just claim centrepieces of Western culture, but they do this in one of Western art’s most sacred spaces (Leight, 2018).

Art used to be what was seen in art museums. This means two things; art was almost exclusively displayed in museums in order to shape a proper art audience and these museums shaped the narrative of art history (Belting, 2009). During the music video of APESHIT the art galleries in the Louvre are criticized for being filled mostly with neo-classical French paintings. These are paintings by white artists with white subjects. The glimpses the viewer gets from these art galleries are followed by faces of people of colour. These people are most often displayed as slaves or subjugated figures in artworks.

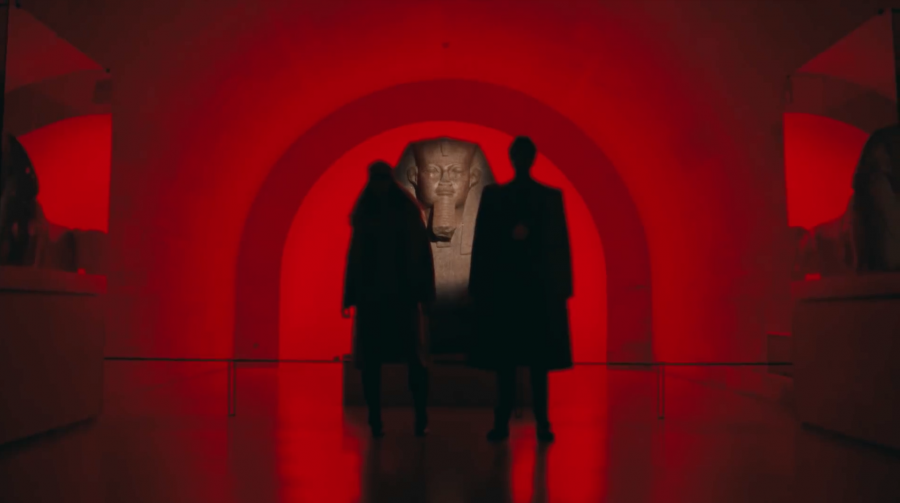

Additionally, the music video of APESHIT criticizes the deliberate disregard of museums regarding the connection between the history of African and Black art, and Ancient Egypt. The master narrative of Western museums often put Ancient Egypt with Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Neglecting the geographical fact that Egypt is part of Africa (Lang, 2018).

The Carters in front of 'The Great Sphinx of Tanis'.

A New Phase in Art

However, the globalization of art could also symbolize a new phase in art. One of art’s exodus from the patronage of art history (Belting, 2009). According to Tomlinson, globalization doesn’t destroy identity by standardization of cultures but rather it proliferates cultural identities. The process of McDonaldization is and will always be opposed by various practices of identification. With the forthcoming globalization, a strong counter-movement of local identity has risen. This means that cultural identity is not likely to become easy prey to globalization. Alternatively, globalization brings cultural, geographically distant experiences to the intimate spaces of people’s local lifeworld (Tomlinson, 2011). Culture used to be bounded to a specific geographical space. As a result of globalization, culture is everywhere and can be practised everywhere. Before, people had to travel between places over significant distances in order to come across different cultures. Nowadays, one can find a more variety of cultures and identities without travelling far (Nederveen Pieterse, 2020). Without globalization, there would still be only internally homogenous localities. No one would be aware of the world outside their own world.

For example, a relatively new form of art is global art. Global art challenges the perpetuity of the Eurocentric view of art. In contrast to the Western art narrative, global art is always created as art whatever the definitions of art may be. And while Western art claims competence is the only suitable method for discussing art, global art rejects the ideals of modernism and does not imply a global concept of what has to be art. It insists on its own traditions and narratives when defining cultural artworks (Belting, 2009). Moreover, Museums of Modern Art are getting replaced more often by museums of Contemporary Art. The latter celebrates contemporary art productions without geographical borders and without the narrative of Western modern art (Belting, 2009).

This means that even when there is an increase in the standardization of art by the Western world, this doesn’t mean the demolishment of non-western identities in art.

Taking Back the Narrative

The APESHIT music video has not only become an iconic pop-cultural moment by one of the most beloved couples in the music industry; but also an embodied disruption that critiques systematic power structures in the art industry. It is because of statements like APESHIT that the Western monopolization of art is globally made aware of and encourages artists from neglected cultures by the West to enter the world stage. Demanding inclusion and visibility of one’s culture in the narrative of art.

APESHIT scrutinizes the monopolization of art by the West and the exclusion of the display of non-Western artworks and art subjects in the Western art narrative. The Carters do this by taking over the Louvre and diverting the attention the valuable artworks usually get to the people of colour shown in the music video. This act alone exhibits power. Power that is needed in order to take back the narrative.

The Carters in front of the ‘Mona Lisa’ by Leonardo Da Vinci. This time with their faces towards the camera.

References

Bal, M. (2009). Working with Concepts. European Journal of English Studies, 13-23.

Belting, H. (2009). Contemporary Art as Global Art: A Critical Estimate.

Gemmill, A. (2018). A guide to the artwork featured in The Carters’ ‘APESHIT’. Retrieved from Dazed.

Nederveen Pieterse, J. (2020). Globalization & Culture: Global Mélange (Vol. Fourth Edition). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Tomlinson, J. (2011). Globalization and cultural identity. In L. A. Jensen, Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 285-301). New York: Springer.