Being transracial: how fluid is the cultural category of race?

On June 26th, 2021, Oli London, a British internet personality and singer, posted their YouTube video titled ‘Being KOREAN…’. In this video, the infamous influencer shares their new – and obviously progressive – identity with the world. Not only did London come out as non-binary, but also as a 'transracial' Korean person, with pronouns that fit this identity: they/them/Korean/Jimin. Since 2013, London has undergone plastic surgery 18 times to look like South-Korean singer-songwriter Park Jimin, who is part of the immensely popular Korean pop group BTS. London themselves describes this process as ‘racial transitional surgery’ and deemed it crucial, as they had been ‘’very unhappy with who I am deep down for the last eight years.’’ And even though we live in a time where acceptance of minority groups is on the rise, London has gotten major backlash. Critics have accused them of cultural appropriation and others have told them to ‘’go seek help.’’

However, their loyal followers are supportive of them and their decision to come out as a non-binary Korean person. London’s YouTube video has even helped some fans with their own ‘coming out’, as people with a transracial identity did not have anyone to look up to before London took that first, brave step.

The video, where London authentically opens up about their identity and the feeling of ‘’being trapped in the wrong body for your whole life,’’ received some positive, but mostly negative reactions. This begs the question: How fluid is the cultural category of race? In this article, the discourse surrounding transracial identities will be analyzed by taking a closer look at London’s video and its uptake, both on YouTube and Instagram. The aim is to discover what the social meaning is of Oli London’s YouTube video ‘Being KOREAN…’ and what the video and its uptake indicate about our acceptance of transracial identities?

Analysing discourse on transracial identities

To explore the discourse surrounding transracial identities, two social media posts – including London’s ‘coming out’ video – and two comments were analyzed qualitatively by looking at their multimodal and indexical qualities. Moreover, the concepts intertextuality and entextualization were used to ground the discourse into ‘histories of use’ – histories that are social, cultural, and political all at the same time (Blommaert, 2005). Lastly, a language-in-action perspective to discourse was employed to examine identity and meaning effects of communication.

A multimodal approach, as put forward by Kress and van Leeuwen (1996), takes into account the various and different modes of representation or communication. These modes, such as text, speech, color, or image, are central to meaning-making processes and identity performances. Different modes allow us to make meaning in different ways, as they all have certain affordances. An image, for example, is capable of making meaning but does so in a different way than sound does. Put together, modes create a richer and fuller meaning than a single mode would be able to do. To explore the discourse surrounding transracial identities, multimodal discourse analysis was conducted on London’s six-minute YouTube video and a fan’s supportive Instagram post – along with two comments.

Moreover, the concepts intertextuality and entextualization deserve a more detailed explanation. Intertextuality, which is often ascribed to Bakhtin, refers to an interdependence of texts in relation to one another, as they can influence, reference, build on, or even inspire each other. In the words of Blommaert (2005), intertextuality refers to the fact that ‘’whenever we speak, we produce the words of others. We constantly cite and re-cite expressions, and recycle meanings that are already available.’’ Words are never neutral, and the expressions used by London (and their supportive fan) – ‘I’m coming out’, for example – can be traced back to LGBTQIA+ linguistics and thus have a history of use. By entextualizing – successively or simultaneously decontextualizing and recontextualizing certain discourses (Blommaert, 2005) – typical queer lingo, London might receive validation from the outside world for their transracial identity.

Lastly, it should be noted that, apart from referential meaning, acts of communication produce social or indexical meaning (Blommaert, 2005). An utterance or sign may thus index or point to certain social norms, roles, or identities. The affordances of indexicality were used to find the social meaning behind London’s video and the audience’s uptake.

London's 'Being KOREAN' video

Oli London’s YouTube video ‘Being KOREAN…’ is distinctly multimodal. By identifying the various modes of interaction present in the video, which together convey one message, the meaning of London’s video can be found.

Figure 1: Screenshot of Oli London’s YouTube video on coming out as non-binary and Korean.

London’s six-minute video was posted on the 26th of June, 2021, and is, at the time of writing, watched approximately 865.000 times. The video has received 4,1 thousand likes and 71 thousand dislikes (see Figure 1). London’s spoken words, posture, appearance, gestures, and the hotel room-like background of the video – including the recorded sounds – simultaneously interact to convey a certain message.

London’s appearance indexes their identity, namely that they are (and look and feel) Korean

Firstly, London’s spoken words are a huge part of the video’s message. London starts off by saying that they have ‘’taken courage from other incredibly brave people that have come out already,’’ and that it is ‘’pride month at the moment,’’ which is the ‘’best time to come out and add a voice of strength to the LGBTQIA+ community.’’ They are ‘’coming out as non-binary,’’ and their pronouns are ‘’they/them/Korean/Jimin.’’ They ‘’identify as Korean,’’ as they ‘’do look completely Korean and feel Korean,’’ after having undergone their ‘’racial transitional surgery’’ consisting of ‘’18 plastic surgeries.’’ They ‘’want to take the brave step’’ to come out because they are sure ‘’there are many other young people out there that do identify as Korean, and don’t have the strength to come out or don’t have the words to express it.’’ With their words, London wants to make clear that transracial identities exist and should be seen as normal. They express the difficulty of being ‘’trapped in the wrong body for so long,’’ and hope to encourage others to come out after they bravely took that first step and paved the way for others to explore and express their (transracial) identity.

London’s appearance indexes their identity, namely that they are (and look and feel) Korean. They have undergone 18 surgeries so far, and in the video, they zoom in on their eyes to show the latest surgery they have undergone. Their eyes now resemble, according to them, the shape of typical Korean eyes, which makes London ‘’finally’’ look ‘’completely Korean’’ and is ‘’part of the transition.’’ Additionally, London’s relaxed posture, their hotel room-like background, and the sounds of a busy street all add to the message of the video. The use of these modes attaches a certain degree of authenticity to London’s message. They apparently did not care about their environment or loud noises interrupting them and just wanted to share their new identity with the world, even though they found it difficult. The fact that this video has been recorded in one single go – and thus resembles the popular YouTube vlogging format – also adds to the authenticity of the video, as adding edits or manipulations would mean the video was more of a 'construction' rather than a genuine talk on identity expression. Put together, these modes index or point to a sincere and authentic identity performance. With their video, they want others to know that this is really how they feel and that transracial identities really do exist.

What is also important to note, is that London entextualizes typical queer lingo

Moreover, the use of spoken words makes London’s appearance (their ‘’Korean look’’), the simple background, their laidback posture, and the sounds understandable. These modalities, in this case, do not speak for themselves and need to be made clear by spoken language. London’s repetition of certain words and phrases shows how much they would value both being accepted by society as a Korean person and being seen as a role model (or ‘’champion’’) for other (non-binary) transracial people. The emphasis on words like ‘can’ – ‘’in 2021, we CAN have all these different identities’’ – highlight how London is of the opinion that a transracial identity is just one of the many identities one can identify with nowadays.

What is also important to note, is that London entextualizes typical queer lingo. The decontextualization of phrases like ‘I’m coming out’, ‘feeling trapped in the wrong body’, or ‘transitioning’ means that London has pulled these phrases out of their original context; a context in which LGBTQIA+ people use these words to come to terms with and express their identity. London recontextualizes these phrases into a new context, namely that of transracial identities. With this, London claims transracial identities are part of the LGBTQIA+ community and should be looked at and treated the same as lesbian, gay, transgender, or other non-cis or non-straight identities. Words are intertextual, never neutral, and certainly have a history of use – as do LGBTQIA+ phrases and expressions. The hard work of LGBTQIA+ people and activists has ensured that LGBTQIA+ identities are now more accepted than ever, which also gives these phrases a more positive or familiar connotation. London cleverly (but maybe unintentionally) makes use of this, and thus of intertextuality, to receive validation from the outside world for their transracial identity.

The audience reacts

London’s message is clear: transracial identities exist, are real, sincere, valid, and are part of the LGBTQIA+ community. They identify as Korean and are sure there are others who also feel trapped in their body and need words of encouragement to ‘come out’ as transracial or express or explore their identity. However, not everyone agrees with London’s view on transracial identities. Some accuse them of cultural appropriation and others of ‘’hiding behind the LGBTQIA+ community as a cover-up.’’ This group of people, which, judging from the number of dislikes on London’s video, are in the majority, are of the opinion transracial identities cannot exist.

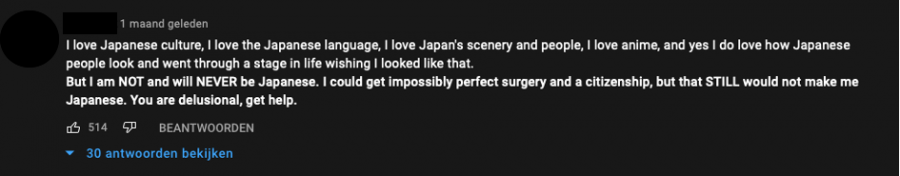

Figure 2: Popular comment on London’s YouTube video, claiming that transracial identities do not and cannot exist.

Figure 2 shows a popular comment that is posted in reaction to London’s video. The commenter clearly thinks transracial identities cannot exist and even calls London delusional for believing so. The user makes use of the modality text, both lowercase and bold uppercase. By capitalizing the words ‘not’ and ‘never’, the user highlights the impossibility of London (or others) being able to identify as Korean (or other races). Additionally, by capitalizing the word ‘still’, the commenter highlights that they could do everything to try to be Japanese – ''get impossibly perfect surgery and a citizenship,'' – but that absolutely nothing would make them so (as they are, according to their own interpretation of what being a certain race means, not Japanese). This indexes that this user believes there are other requirements that should be met for a person to be of a certain race. However, by saying that they (also) went through a stage in life wishing they looked like that, the user, in a way, sympathizes with London as well. Part of the comment thus indexes a certain feeling of relatability within this user. This relatability, however, completely disappears further on. The phrase ‘’you are delusional, get help’’ indexes that, for this user, London went too far in their appreciation of Korea, its culture, and its people. The user thus essentially classifies London’s transracial identity as abnormal.

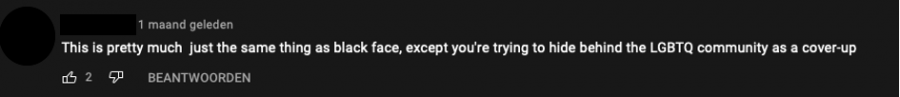

Figure 3: Comment on London’s YouTube video, criticizing London for their transracial identity and its similarity to blackface.

The disapproving discourse surrounding transracial identities does not stop there. Figure 3 shows another comment posted on London’s video. This commenter compares London’s transracial identity with ‘blackface’, which is a word that certainly has a history of use. According to Oxford University Press (n.d.), the word blackface is used ''to refer to the practice of wearing make-up to imitate the appearance of a black person.’’ Nowadays, the practice is regarded as highly offensive. The commenter makes use of intertextuality and recycles meanings that are already available, namely that of blackface, to describe the practice of identifying as transracial. Essentially, the user entextualizes the word blackface by decontextualizing it out of its original context and recontextualizing it into a new context; that of transracial identities. By saying that London is doing the ‘’same thing as blackface,’’ the commenter implies that London is imitating the appearance of a Korean person, which is, just like blackface, highly offensive. This indexes that the user does not believe in London’s transracial identity and even finds it insulting. Additionally, by saying that London is ‘’trying to hide behind the LGBTQ community as a cover-up,’’ the user implies that London’s categorization of transracial identities as belonging to the LGBTQIA+ community is just to conceal how offensive and abnormal these identities are.

Figure 4: Instagram post of an Oli London fan, coming out as ‘’Philippines,’’ and explaining transracial identities.

However, not everyone finds transracial identities abnormal or offensive. As illustrated in Figure 4, London’s ‘coming out’ has helped others understand and come to terms with their own transracial identity. This Instagram user has come out ''as Philippines'' and is ''proud'' of this. Additionally, they explicitly state that transracial identities are part of the LGBTQIA+ community and that they are similar to transgender identities. By saying that it is about ‘’people being born in the wrong country, with the wrong race and nationality,’’ (just like being born in the wrong body, with the wrong sex) typical queer – or transgender – lingo is, once again, being entextualized. Even though the user seems genuine in expressing their new transracial identity, it is worth noting that maybe the user’s claim cannot be taken at face value given the culture of trolling and irony online.

The modalities visible in the post are text, color, image, emojis, hashtags, fonts, comments, and the number of likes – of which the text is the most important. The picture used by the user is a picture of Oli London, which shows the user is a fan of them. The hashtags also show the user’s fondness for London (#olilondonfan, #olilondonfanpage). The caption is ‘’Do you support us?’’, together with the pleading face emoji, which represents the typical face one makes when pleading or trying to win someone’s sympathy or compassion. This indexes that the user hopes to receive support from people seeing the post, and even wants people to sympathize with them for their transracial identity. This, however, did not happen, as most of the comments are negative. ‘’No, we call that racism:)’’ and ‘’TRANSRACIAL PEOPLE DONT EVEN EXIST’’ are two examples of those non-supportive comments. Moreover, by entextualizing queer lingo, the user can – just like London with their video – (maybe unintentionally) take advantage of the more positive reputation of the LGBTQIA+ community, to normalize transracial identities.

Entextualizing transracial identities

By making use of various interacting modalities, such as speech, appearance, gestures, posture, sound, and background, London was able to convey a certain message with their YouTube video. The emphasis was put on the realness and validity of transracial identities, as London had felt ‘’trapped in the wrong body for so long,’’ and is now finally happy after having undergone ‘racial transitional surgery’. With their video, London hopes to encourage others to ‘come out’ after they bravely took that first step and paved the way for others to explore and express their transracial identity. Additionally, London’s authentic and sincere identity performance indexes that they really do feel and identify as Korean and that transracial identities really do exist. By entextualizing typical queer expressions, London can make use of the LGBTQIA+ community’s familiarity with normalizing transracial identities.

Moreover, London’s coming out helped a fan come to terms with their own transracial identity. This user, too, hopes to receive validation from the outside world for their identity and ties transracial identities to the more accepted and familiar LGBTQIA+ community by describing their similarity to transgender identities. However, it is worth noting that maybe the user’s claim cannot be taken at face value given the culture of trolling and irony online.

Even though London and their fan were hoping for validation, the comments on either of their posts show the general hostility and antipathy that is felt towards transracial identities. By entextualizing the word ‘blackface’, one commenter expresses the offensiveness of transracial identities. Another commenter claims transracial identities cannot exist and that people identifying as transracial should ‘’go get help'’. Judging from these comments – and from the number of dislikes on London's video, it can be concluded that racial identities are mostly seen as permanent and fixed, rather than fluid and impermanent.

References

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A Critical Introduction (Illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Kress, G., & Leeuwen, T. V. (1996). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. Routledge.

London, O. (2021, June 26). Being KOREAN. . .. YouTube. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

Oxford University Press (OUP). (n.d.). Blackface. Lexico.Com. Retrieved December 10, 2021.