Globalization and the emergence of Chinglish and Greeklish

Globalization has profound cultural effectsWe are living in a world of movement. People, goods, and information move with unprecedented volume and speed. And of course, languages do not remain unchanged. To be fair, they have never been the static, isolated entities that many expect them to be. As soon as a language comes in contact with other languages, their values and meaning get to be redefined almost immediately.

In the context of globalization, this process is happening with greater speed. English, despite being the world’s lingua franca, is no exception from this phenomenon.

No one can deny the remarkable spread of the English language in the latter half of the 20th century.

Today, English is everywhere. On the Internet, all over social media, in that funny Hollywood movie we watch with our friends, from the endless stream of tourists pouring into our countries every year. Do you realize how many times you absentmindedly insert an English word in the middle of a casual conversation? Or how many times English appears on your social media feeds, sandwiched between words from your mother tongue? It feels like English is invading our lives in every possible way.

However, it turns out that not only English affects us; we, as users of English, affect it as well. We learn the language, add its words to our linguistic repertoire, and then use them in our daily lives. Some people even localize English by combining the elements of English and their native language to create new words. Sometimes because we want to have a bit more fun with language.

At other times, it is simply more convenient and less time-consuming, especially when you are on the Internet, where language norms are not strict and communication is expected to be quick. And so, new varieties of English are born, not by its native speaker but by the people who learn English merely as a foreign language. In this article, we will present two new English varieties that are the result of localization: Chinglish and Greeklish.

Case in China: from English to Chinglish

In the context of World Englishes (Kachru, 1992), Chinglish (or China English)– namely the English variation used by Chinese speakers worldwide – can be considered of fundamental importance either in the sphere of world migration, or in linguistic terms, since it may be classified as a viable English variety thanks to the huge demographic potential of its speakers.

This new form of English with distinctive Chinese characteristics not only serves a variety of communicative and social purposes but also helps to reflect the Chinese social upsurge, or societal problems.

The most influential internet Chinglish word in 2010 was gelivable, which derived from Chinese ‘给力’ meaning "brilliant" and "excellent". The morpheme Ge(the Chinese word of gei 给)means “give”, and li (力)is equivalent with English of “strength” or “power”. The two morphemes combined together literally mean “give strength”. It was coined by Chinese netizens to describe the emotion that the reality meets their expectations, conveying the comment “YES! THIS IS IT!” (Jing, 2017) .

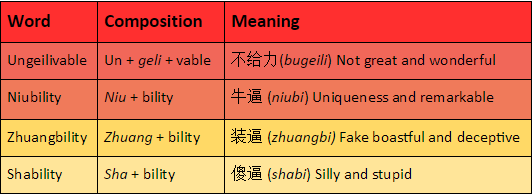

The word is clearly a lexical innovation based on a derivation method in which a new word is composed of roots and affixes. In "ungelivable" the prefix -un and the suffix -able are attached to a Chinese verb phrase geli to form an adjective-like English word. It is used to express the feeling of being unsatisfied, lousy and unpleasant. Although this coinage is somewhat strange, it makes sense not only to native Chinese speakers who are able to master English, but to native English speakers who may have limited familiarity with the Chinese language.

With the word geilivable emerging in the online world, a large number of Chinese netizens have started the trend of creating new words of Chinglish to comment, chat, tweet and post. Owing to the high-speed transmission of the Internet, this emerging online feature of Chinglish spread worldwide within a few hours. Moreover, this playful and informal way of using foreign language also enables Chinese people to increasingly chase this trend as fashion, and use English in a pragmatically interesting way.

Similar word structures can be seen below:

Case in Greek: Emergence of Greeklish in globalization

Greece is a country greatly involved in tourism and trade, so the use of Roman Alphabet to write Greek is not a new concept. Someone might think the use of Greeklish is a consequence of the emerging technology and the easiness caused by a non-switching keyboard. However, the truth is that early CMC posed a technical limitation in non-Roman Alphabet languages, such as Greek.

Moreover, the common code in early computer systems, ASCII, supported only basic Roman characters, with few digits and symbols. It was in 2005 when Unicode Standard included more than 50 languages, including Greek. The technological and linguistic limitations of the early days were the primary reason for the spread of the English language and characters, not only in Greece but also in the global context.

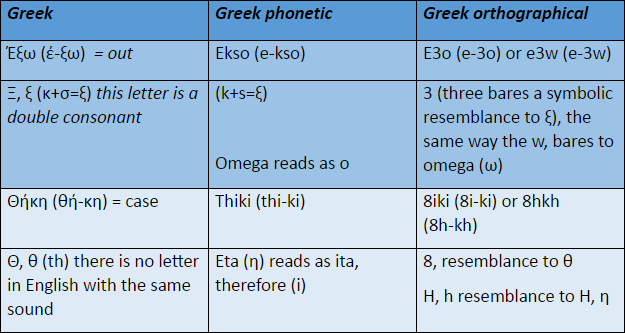

What do we really mean, when we say Greeklish?

The Greeklish “language” if we may call it that, can be either phonetic or visual/orthographical.

Greeklish has surpassed the primitive use for lack of a better option and has extended its use in punctuation symbols such as the question mark (?) [English version] disregarding the (;) [Greek version]. Several words have been borrowed from English, even though there’s a Greek translation: “video”, “pc” (computer), “e-mail”, “humor”, “group”, “internet”, words like “sorry”, “please”, “yes”, “no”, “hi” and “hello” (Tseliga, 2007). They are used mainly as a form of linguistic abbreviation.

A study conducted by the Department of Early Childhood Education of the University of Western Macedonia shows that the use of Greeklish by schoolchildren is affecting not only their spelling skills but also the correct insertion of accent and punctuation marks. This ultimately might pose a threat to the Greek language.

A lot of criticism has come along with concerns for the status of Greek language in a globalized world. The social attitudes towards Greeklish can be divided into three categories. The retrospective trend sees Greeklish as a threat to the Greek language.

The prospective trend argues that Greeklish is merely an adaptation for communicative media from a technophobic point of view.

The resistive trend interprets Greeklish as a sociocultural exchange that takes place due to globalization and its negative effects of it. A “smaller language” like Greek isn’t only a means of communication within the country but also plays a strong role in national identity and history. The resistive position calls for equality of languages in a rapidly globalized environment.

Is Blended English a good thing or bad thing?

Again, language is essentially dynamic. Recently, the birth of new English varieties both online and offline as a result of globalization has become a contested topic. Some think that globalization will result in “the hegemony of English”, which ultimately leads to the disappearance of other “weak” or “inferior” languages. Tsui (2017) also mentions similar and resurging debates over English’s being an official language in China since it is believed to threaten the national identity and linguistic heritage among Chinese people, particularly the young generations.

This concern is also often observed in developing countries where people have to depend on English to have access to the outside world and get involved in the globalization process (Dahlman, 2007). Therefore, the youth community as a typically globalized and diversified group is more likely to use English rather than their native language to meet the demand for cross-cultural communications.

The Internet-based globalization process “gives a new and virtual planetary presence to hundreds of languages and cultures through millions of Websites, mixing text, and videos”.

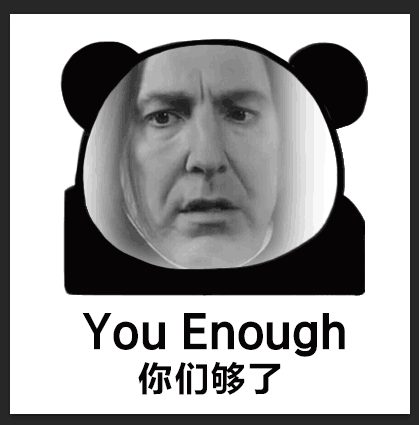

The highly diverse, accessible, and complex online media culture is thriving, often by sacrificing the traditionally fixed and prescribed linguistic rules such as grammar, because they are seemingly overshadowed by new forms of expression like “memes” – grammatically incorrect but sociolinguistically meaningful. It is through such a globalized platform that new varieties of English come into being and become functional. Yet they also bring the risk of non-standard or irregular language use among youth community.

*Translation: I have had enough of you

*Translation: A: Do you know how we say air condition in English? B: Air Condition. A: They took it from us again! Seriously! Mercy Somewhere!

On the positive side, the penetration of English into other languages also contributes to the spread of some marginal or non-mainstream cultures such as hip-hop (Varis & Wang, 2011). Particularly with the help of Internet and information technology, marginal culture is also involved in the globalization process, which creates “a vast and layered market” for a larger diversity of cultural expressions.

In order to better spread both traditional cultures and current youth identities, new vocabularies and phrases also emerge in order to help “linguistic and cultural others” to familiarize some local or regional concepts. Furthermore, there is evidence for positive effects of Chinglish on English education in colleges (Jing, 2010). Therefore, blended English also has bright sides, on both cultural and linguistic levels.

However, some people hold a rather tolerant and open attitude towards blended languages and see them as a normal by-product of globalization especially on the social media. “Language is unique to cultural and historical context, and preserving world’s linguistic heritage and witnessing the emergence of new ones are both important in expanding the linguistic melting pot”.

In this sense, language is also adapting to the new globalized world, along with the young generations that speak it, and this evolving process deserves attention and respect at all times. Rather than remaining static, language keeps changing in the process of being used for different purposes, and becomes localized into various communities and cultures.

References

Dahlman, C. (2007). Technology, globalization, and international competitiveness: Challenges for developing countries. In Industrial Development for the 21st Century: Sustainable Development Perspectives (pp. 29-84), United Nations.

Jing, X. (2010). Chinglish or English: Reflections on cultural aspect of foreign language teaching in China. Journal of Zhongzhou University, 2, 38-50.

Jing, C. (2017). Internet Chinglish as a Manifestation of FL/SL Learners’ Language and Conceptual Socialization. DEStech Transactions on Social Science, Education and Human Science, (icesd).

Kachru B. (1992), World Englishes: approaches, issues and resources. Language Teaching, 25, 1-14.

Koutsogiannis, D. & Mitsikopoulou, B. (2007). Greeklish and Greekness: Trends and Discourses on “Glocalness”. In B. Danet & S. C. Herring (eds.), The Multilingual Internet: Language, Culture and Communication Online (pp. 142-162). Oxford: University Press.

Tseliga, T. (2007). “It’s All Greeklish to Me!” Linguistic and Sociocultural Perspectives on Roman-Alphabet Greek in Asynchronous Computer Mediated Communication. In B. Danet & S. C. Herring (eds.), The Multilingual Internet: Language, Culture and Communication Online (pp. 116-141). Oxford: University Press.

Tsui, A. B. M. (2017). Language policy and the construction of identity: The case of Hong Kong. In A. B. M. Tsui & J. W. Tollefson (eds.). Language Policy, Culture, and Identity in Asian Contexts (pp. 11-32). Routledge.

Wang, X., Spotti, M., Juffermans, K., Cornips, L., Kroon, S., & Blommaert, J. (2014). Globalization in the margins: Toward a re-evaluation of language and mobility. Applied Linguistics Review, 5(1), 23-44.