MeWe: Mark Weinstein’s technological utopia

For most social media platforms, your data is worth money. The time when we only came across posts from our friends is over. Advertisements are almost impossible to avoid - and we are only getting more. Meta, the owner of Facebook and Instagram, announced in October 2022 that it would show advertisements in (even) more places on Instagram (Meta, 2022). Furthermore, since we are dealing with the interconnectedness of social and technical elements in social media, and more specifically the socio-technical assemblages named algorithms, it is just partly us who decide what we see on our feed. Does this mean the end of privacy and self-control? Not when it comes to Mark Weinstein, founder of the social media platform MeWe. Nowadays, people are more than ever aware of (their lack of) privacy. With their focus on data privacy, MeWe has responded to that fact. This article unravels how Mark Weinstein questions the surveillance capitalist hegemony of Silicon Valley and discursively constructs a technological utopia by translating his beliefs into the social media platform MeWe.

The distorted purpose of the social media industry

In 1989, the internet was developing quickly. Millions of computers were already connected. With the realization that computers could share information in a more effective way when using ‘hypertext’, Berners-Lee developed the World Wide Web. Since university scientists Berners-Lee and his team agreed that the Web had far greater potential, the Web soon became freely available for everyone (History of the Web, n.d.).

Less than a decade after the invention of the World Wide Web, Weinstein and his team followed Berners-Lee's vision and developed the platforms SuperFamily and SuperFriends. Weinstein's intentions with those platforms were clear, namely "to use the free and open communication capabilities of the Web to help bring friends, family, and like-minded people together through the magic of technology" (Weinstein, 2019a). As his platforms were one of the first, Weinstein calls his creations "pioneering" and argues that his platforms paved the way for "the social media world of today" (Weinstein, 2019a).

Other platforms followed and in 2004, Mark Zuckerberg developed Facebook. Facebook quickly became very popular and was presented as an "altruistic platform that would connect the whole world". However, as Facebook gained popularity and rapidly spread at a remarkable pace, Weinstein noticed that "their true objective was to spy on their users, aggregating and exploiting their users’ personal data through targeting and manipulation in a new business model now known as surveillance capitalism" (Weinstein, 2019a). At that time, Weinstein had already sold SuperFamily and SuperFriends, but as he felt that Facebook distorted the purpose of the social media industry that he helped create, he was compelled to speak out.

"I think it is weird and creepy if I am doing anything online and I do not know who is going to see it."

In an interview with Fox News in 2012 regarding to Facebook, Weinstein said: "I think it is weird and creepy if I am doing anything online and I do not know who is going to see it". He argued that "privacy would become the next big wave’ and advocated for ‘privacy-by-design within social networks whereby tech companies would build privacy into their DNA". It was this notion that led him to found MeWe: The first social media platform engineered with privacy-by-design (Weinstein, 2019a).

Silicon Valley as ideological state apparatus

Ideologies present ideas, behavior, relations, and thinking within a specific setting. This makes them of interest to analyze. However, the term ideology is served in a bad way by scholarship. There are many definitions of the term, which often contradict each other or the approach diverges (Blommaert, 2005, p.158). It often occurs that, when studying ideologies, they are considered to be something negative. It is often argued that ideologies are a set of inauthentic ideas and beliefs that have been spread through propaganda. This keeps people from 'thinking for themselves' and therefore ideologies are labeled as wrong. Putting these prejudices aside, the definition of ideology used when studying culture and society is used in this article, namely any collection of socially constructed concepts that shape both behavior and cognition within any sphere of life.

Blommaert argues that ideologies within discourse analysis are a fruitful topic of investigation. This has a clear reason: almost every major scholar has identified discourse as a site of ideology (Blommaert, 2005). There is a two-fold distinction: on the one hand, ideology can be described as "a specific set of symbolic representations serving a specific purpose, and operated by specific groups or actors" (Blommaert, 2005, p.158). On the other hand, ideology can be defined as "a general phenomenon characterizing the totality of a particular or political system, and operated by every member or actor in that system" (Blommaert, 2005, p.158). However, Blommaert, who follows Barthes in this matter, rather sees the concept of ideology as layered.

Digital media are math-powered applications of data economy that are built by fallible human beings. These applications are not neutral but can be seen as reflecting the norms, values, and goals of their makers and having algorithmic agency. Algorithms involve the interplay between technical components and social factors. The built-in algorithms thus can be understood as socio-technical assemblage: The expression and influence of social media users is not completely 'free', but rather a result of the socio-technical interplay among the user, the platform(s), their followers, and the wider community in which the user participates (Maly, 2020).

Digital media are ideologically constructed through discourse and therefore can be analyzed as ideological apparatus. Since this ideological apparatus influences how one communicates, how news is consumed, how the media field is organized, and how the economy is structured, it is argued that it consists of dominant social structures. These social structures are described by Althusser (1971). He argues that despite that media are formally outside state control, they serve to transmit the values of the state, to interpellate the individuals affected by them, and to maintain order in a society, especially to reproduce capitalist relations of production. When we label digital media - in particular Silicon Valley - as ideological state apparatus, we thus understand them as a huge force, economic as well as ideological. As this article shows, MeWe sets out a different ideology and provides an alternative to this hegemony by opposing the surveillance capitalist culture that prevails in Silicon Valley.

Methodology

Weinstein labels himself as an advocate for privacy, especially in the digital world, and speaks out regularly regarding this topic. With his social media platform MeWe which is engineered with privacy-by-design, Weinstein provides an alternative for the social media platforms in Silicon Valley, thus questioning its surveillance capitalist hegemony. This analysis explores how Weinstein uses his beliefs to discursively construct a technological utopia through his platform MeWe. To do so, a qualitative research method was used.

The analyzed data was open access and twofold. The blogs that Weinstein himself wrote and published on the website Medium.com served as the basis of the data. These blogs were chosen because on the one hand, the content comes directly from Weinstein himself, and on the other hand the blogs were written on Weinstein's own initiative. Therefore, they provide a solid insight into Weinstein's discourse. To answer the question of how Weinstein uses his beliefs to discursively construct a technological utopia through MeWe, the FAQ page of the social media platform was analyzed as well. The FAQ page was chosen since its discourse explains and amplifies the norms, values, and beliefs the platform propagates.

To examine the ideological beliefs on the organization of society and the restructuring of power that are shown in the discourse of Weinstein as well as MeWe’s, a critical perspective on discourse analysis was adopted as the main research approach (Blommaert, 2005; Verschueren, 2013). Since the study of discourse must be interpreted in light of the social and political context it is used (Cameron et al., 2020; Blommaert, 2005), contextual data was taken into account as well. In this way, "the relations between language usage and the particular purpose for which and conditions under which it operates" were established (Blommaert, 2005, p.14), leading to the uncovering of implicit meanings.

Neither Weinstein nor MeWe have complete freedom in the ideas and messages they propagate and communicate. In order to gain greater acceptance, both as individuals and as platforms, the discourse must originate from the language users who possess diverse linguistic repertoires that shape the possibilities of language use. These repertoires are constructed and structured in unequal ways within every society, limiting the potential for some individuals to express themselves fully (Blommaert, 2005, p. 15). This emphasizes the importance of analyzing the discourse of both Weinstein and MeWe in order to uncover more widely accepted beliefs.

Mark Weinstein and his purpose for the social media industry

As stated in the introduction, Weinstein is not new to the world of tech and social media. In his blog Remarkable MeWe Realizing Web Inventor’s Extraordinary Privacy Vision, which is partly summarized above, Weinstein sets out the background on his current view. His discourse shows that he has trouble accepting that the dominance of platforms like Facebook has disrupted the purpose of the social media industry he helped create. With the unethical way in which platforms like Facebook act, "free expression, privacy, and democracy are at stake" (Weinstein, 2020). Weinstein identifies himself as the advocator for privacy-by-design, which translates into how the platform MeWe was created. He advocates for a Web in which users are not censored based on their political or ideological viewpoints. Furthermore, users should have full control of their data.

"You see, Berners-Lee didn't invent the Web for companies or governments to spy, target, manipulate, and collect or sell users' data."

When delving deeper into Weinstein’s discourse, it is striking that he regularly emphasizes the start of the World Wide Web. For example, Weinstein emphasizes in his blog that the inventor of the Web, Berners-Lee, also speaks out against the negative consequences of the Web and social media. Furthermore, he presents his position in such a way that if one does not follow it, one abuses Berner's-Lee invention. Weinstein does this, for example, by saying: "You see, Berners-Lee didn't invent the Web for companies or governments to spy, target, manipulate, and collect or sell users' data" (Weinstein, 2019a). This shows that Weinstein’s discourse aligns with the discourse of Berners-Lee. He frames himself as a true advocate of Lee's vision and presents MeWe as working in that tradition. By recycling the meaning of Berners-Lee, Weinstein explicitly shows that his conception of the internet is in line with the founders – and that major tech companies are distorting that legacy. Weinstein uses this intertextuality to claim authority (Blommaert, 2005, p.46).

Even though Weinstein’s blogs on Medium.com are mostly about privacy or privacy issues within other social media platforms, he mostly manages to point himself or his platform out. For example, he writes in his blog on the Yahoo! hack in 2016: "I know this practice. As founder of MeWe, the next-gen social network, we protected users with an industry-exclusive Privacy Bill of Rights" (Weinstein, 2016). In his blog Facebook Profits by Disrupting Our Democracy he writes: "MeWe has no political bias — left and right all enjoy the platform, and MeWe’s TOS restricts bad elements while allowing free speech" (Weinstein, 2020). From this perspective, his discourse not only describes how Weinstein wants the Web to become the free and accessible place it was once intended to be and which he helped build. By emphasizing that MeWe does things differently than the platforms mentioned in its blogs, sells his platform. Weinstein's discourse is therefore at least in part a marketing discourse in which MeWe is plugged as the alternative driving the change.

Additionally, Weinstein often involves important people in his discourse. He for example writes in his blog: "On the 25th anniversary of the Web, back in 2014, when MeWe was known by its original name, Sgrouples, Berners-Lee did an interview with CNET and stated: “There is a social network, Sgrouples, that specifically is privacy-aware. You can share stuff there that they won’t share with anybody else."" (Weinstein, 2019a). In another blog, Weinstein writes: "I was honored to meet Dr. Cavoukian in 2012 when she named me Privacy by Design Ambassador" (Weinstein, 2019b). This shows that Weinstein not only uses intertextuality by aligning his discourse with the inventor of the Web, but he also positions himself in a long tradition of internet pioneers and people who think privacy is important. He does so to make a distinction between himself and the current social media giants in Silicon Valley who practice surveillance capitalism, such as Facebook and Google.

MeWe: From Weinstein's beliefs to a technological utopia

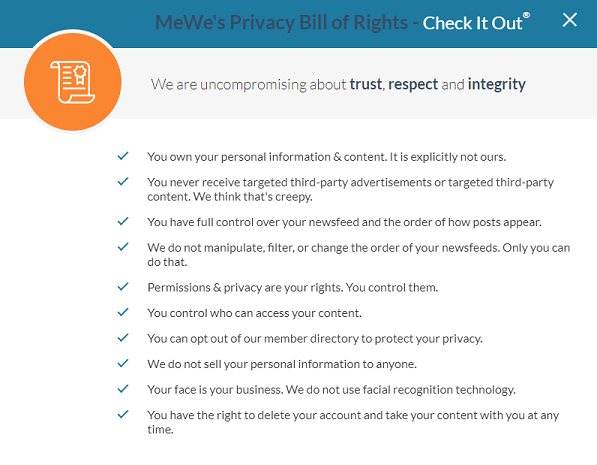

When taking Weinstein’s privacy discourse into account, it can be argued that MeWe is created to bring the right to privacy back. MeWe is set in the market as the first social media platform engineered with privacy-by-design. Privacy-by-design is a concept established by Dr. Cavoukian in 1995 and can be seen as a framework in which "privacy is proactively embedded into the creation and operation of IT systems, networked infrastructure, and business practices" (Weinstein, 2019b). MeWe additionally distinguishes itself by not showing any advertisements on the platform, no targeting, and no newsfeed manipulation. MeWe states that the users' data is owned by the users themselves and therefore will not be sold (MeWe, 2022). They endorse this by referring to "the protection of MeWe's Privacy Bill of Rights" (figure 1).

Figure 1: Privacy Bill of Rights

It is MeWe’s privacy-by-design in particular that makes the platform a break away from surveillance capitalism. Surveillance capitalism is a phenomenon that "claims human experience as raw material for translation into behavioral data" (Zuboff, 2019, p.8). Zuboff argues that "surveillance capitalists are on an endless quest to acquire ever-more predictive sources of behavioral surplus", with an aim to maximize their profit. The motivation for this so-called ‘extraction imperative’ is in the desire for huge profits. When behavioral surpluses are extracted the more and the better, companies can make more profit. By embedding privacy in every layer of MeWe’s design, the platform qualifies as an alternative platform that deviates itself from surveillance capitalism as performed by big tech companies in Silicon Valley, thus questioning its hegemony.

"Bottom Line: It is a false myth that our data is what we have to give up to have a great social media experience"

That MeWe explicitly questions the hegemony of surveillance capitalism also becomes clear when a closer look is taken at the business model of the platform. Whereas big tech platforms such as Facebook, Google, or Instagram are gaining income through the sale of data and advertisements, MeWe takes a different approach. In their FAQ they state: "MeWe is “free forever” because privacy is not something anyone should ever pay for". All the basic features the platform offers can be used for free. There are, however, optional enhancements that users can pay for. In this way, the platform is not financed by advertising revenues or the sale of data, but by the users themselves. Again, MeWe's discourse makes clear the importance of privacy and questions hegemony by underpinning their view of the unethical behavior of other platforms: "Bottom Line: It is a false myth that our data is what we have to give up to have a great social media experience. At MeWe our members are customers to serve, not data or products to sell or target".

As Weinstein fears having no freedom of expression, privacy, and democracy, the discourse of MeWe shows to offer just that. MeWe for example states: "Unlike other social networks, at MeWe we have absolutely no political agenda and no one can pay us to target you with theirs. MeWe is for law-abiding and TOS-abiding people everywhere in the world, regardless of political, ethnic, religious, sexual, and other preferences" (MeWe, 2022). This reinforces the claim that Weinstein's beliefs are directly translated into the platform he has created. MeWe's discourse additionally gives insight into the platform's ideology, which can be labeled as democratic in the libertarian sense. Furthermore, the set of beliefs and values provided by MeWe reveal the ideological infrastructure of the platform.

MeWe implies that when using their platform, users have a choice again. The platform shows that due to their technological changes, people no longer have to be captured in a Web that leads to a de-democratized, no-privacy, and censored society. The discourse of MeWe shows distrust regarding other social media platforms. It is clear that they are aware that many take the giving up of privacy, the ads, and the algorithms for granted. MeWe treats this phenomenon as a "technology-induced transformation of society" (Dickel & Schrape, 2017 p.48). Expressing this in their discourse reinforces the technological-determinism assumption, which, in short, means that the basis of society is formed by technology. As a result of this technological formation, social and cultural phenomena are shaped (Chandler, 1995).

MeWe opposes the phenomenon that is seen as ‘normal’ in nowadays society and shows how things can be done differently with a few adjustments. They explicitly question hegemony by de-normalizing the current state of affairs within Silicon Valley’s surveillance capitalist social media platforms. Rather, MeWe tries to normalize that the Web is a place where the user has complete control over his or her own data and is unaffected by algorithms and advertisements. In this way, MeWe discursively constructs a utopian vision of the Web in which this free, uninfluenced, ad-free view is seen as the ideal.

By allowing their privacy-focused business model to deviate from that of other platforms, MeWe meets one of the key tenets of technological utopianism. Namely the ideology that argues that technological developments are seen as the ultimate solution for structural issues of access and inequality (Levina & Hasinoff, 2017). Furthermore, by emphasizing that MeWe is for everyone, regardless of where they come from, what political preference they have, what their sexual orientation is, or any other preferences, the sense of universalism is created. This, according to Dickel & Schrape (2017), is dominant in utopian discourse as well.

MeWe against the world

This article unravels how Mark Weinstein questions the surveillance capitalist hegemony of Silicon Valley by translating his beliefs into the social media platform MeWe. Weinstein values the original beliefs that formed the basis of the World Wide Web in 1989 (Weinstein, 2019a). Weinstein uses intertextuality to claim authority by recycling the meaning of Berners-Lee, the inventor of the Web (Blommaert, 2005, p.46). In this way, Weinstein shows that his conception of the internet is in line with the founders – and that major tech companies are distorting that legacy. Weinstein’s discourse furthermore shows that he sees himself and MeWe as the ones driving the change in restructuring the Web to become the free and accessible place it once was. To clarify the distinction between him and the current social media giants at Silicon Valley, Weinstein positions himself in a long tradition of internet pioneers and people who believe privacy is important.

MeWe, when taking Weinstein’s discourse into account, is created to bring the right to privacy back. Whereas other platforms perform ‘extraction imperatives’ to gain huge profits (Zuboff, 2019), MeWe does not. By embedding privacy-by-design in the platform, MeWe is the real break away from surveillance capitalism. This claim is reinforced when looking at the business model, which shows that the platform is financed by the members themselves.

MeWe sees the adoption of surveillance capitalism as a "technology-induced transformation of society" (Dickel & Schrape, 2017), which reinforces the technological determinism assumption (Chandler, 1995). It was shown that MeWe opposes surveillance capitalism as ‘normal’ by de-normalizing the current state of affairs within Silicon Valley’s social media platforms. MeWe discursively constructs a utopian vision of the Web in which a privacy-based, free, uninfluenced, and ad-free view is seen as the ideal. They accomplish this view by making technological adjustments to their platform, which causes them to meet the tenet of technological utopianism arguing that technological developments are seen as the ultimate solution for structural issues of access and inequality (Levina & Hasinoff, 2017). MeWe emphasizing universalism contributes to utopian discourse as well (Dickel & Schrape, 2017).

This article not only shows that Weinstein's discourse is directly translated into the platform he has created, but also gives insight into MeWe’s ideology, which can be labeled as democratic in the libertarian sense. The set of beliefs provided by MeWe reveals the ideological infrastructure of the platform. With his MeWe, Weinstein attempts to redefine the ‘new normal’ when it comes to social media usage. Through this restructuring, Weinstein was able to create a technological utopia. 30 years ago Weinstein was one of the pioneers in the field of social media platforms. With his attempt to restructure the Web, nowadays he might be seen as one of them as well.

References

Althusser, L. (1971). Ideology and ideological state apparatuses. In L. Althusser (Ed.), Lenin and philosophy and other essays. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse – key topics in sociolinguistics. Cambridge

Cameron, D., Frazer, E., Harvey, P., Rampton, M. B. H., & Richardson, K. (2020). Researching Language: Issues of Power and Method (Routledge Library Editions: Sociolinguistics) (1st ed.). Routledge.

Chandler, D. (1995). Technological or media determinism.

Dickel, S., & Schrape, J.F. (2017). The logic of digital utopianism. NanoEthics, 11(1), 47-58.

History of the Web. (n.d.). World Wide Web Foundation.

Levina, M., & Hasinoff, A. A. (2017). The Silicon Valley ethos: Tech industry products, discourses, and practices. Television & New Media, 18(6), 489-495.

Maly, I. (2020). Metapolitical New Right Influencers: The Case of Brittany Pettibone. Social Sciences, 9(7), 113.

Meta. (2022, October 4). Helping businesses grow with AI, messaging and video. Meta.

MeWe. (2022). Frequently Asked Questions. Mewe.

Verschueren, J. (2013). Ideology in Language Use: Pragmatic Guidelines for Empirical Research (Reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Weinstein, M. (2016, November 15). Who is spying on you? What the Yahoo! hack taught us about Facebook, Google and WhatsApp. Medium.

Weinstein, M. (2019a, March 29). Remarkable MeWe Realizing Web Inventor’s Extraordinary Privacy Vision. Medium.

Weinstein, M. (2019b, June 23). MeWe – The First Social Network with Privacy by Design. Medium.

Weinstein, M. (2020a, November 7). Government Regulation Won’t Solve “The Social Dilemma”; The Free Market Can. Medium.

Weinstein, M. (2020b, January 21). Facebook Profits by Disrupting Our Democracy. Medium.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism. The fight for the future at the new frontier of power. London: Profile Books.