Multisensory Realities of Authentic Artworks

In September 2021, the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven) opened the first fully multisensory exhibition in the Netherlands, featuring 120 artworks and a range of multisensory tools like touch replicas, scents, musical interpretations of artworks and soundscapes which makes it accessible for visually or audial impaired visitors. To this effect, this paper explores the case of the Delinking and Relinking collection concerning the concept of the authenticity of art described by Walter Benjamin (1969) and the intimacy of the viewers’ interaction with the artworks in the multisensory environment of the exhibition.

Exhibiting Artworks through Mutisensory Realities

At the beginning of the exhibition, the visitors guided by the Smartify app find themselves in a brightly coloured room with the walls fully upholstered with soft carpet (Smartify (official website). Against the contrastive background of the orange wall, one can see a green and blue painting by Picasso - “Buste de Femme” (1943). Next to the original painting, there is another “Buste de Femme” – a white tactile relief of the original artwork, which visitors are free to touch.

A tactile relief of the original artwork by Pablo Picasso

As one proceeds with a multimedia tour, Delinking and Relinking reveal its visual, auditory, olfactory and spatial features providing a multisensory experience to the visitors. This kind of experience is not unusual for visitors to a historical or science museum. Most art museums, however, display visual-only collections, and the spaces where the artworks are exhibited are mostly unembellished and predominantly white.

Most art museums display visual-only collections, and the spaces where the artworks are exhibited are predominantly white

The whiteness of the museum walls was an aesthetic choice of modernity. Throughout the era of modernity, the sense of vision was regarded as primary for architecture, which influenced the design of museum buildings and exhibitions. White, smooth, preferably illuminated museum walls were supposed to create a visually neutral environment for the artworks showing their best features “as individual and independent aesthetic objects with a special "aura" (Pallasmaa, 2014, p. 239). In Delinking and Relinking in the Van Abbemuseum, the artworks are not displayed as autonomous objects suspended in the white ambience of the building. Instead, they become a part of the multicolour, and multisensory contextual narrative of the exhibition.

Authentic Artworks in a Multisensory Exhibition

According to Walter Benjamin, artworks possess something that he called cult value. The cult value can be understood as a set of cultural, social and economic characteristics that make an artwork “an instrument of magic” (Benjamin, 1969, p. 225) to the audience in the same way as a ceremonial object of a cult is seen as an instrument of magic for its followers. Benjamin understood “the formulation of the cult value of the work of art in categories of space and time perception” (1969, p. 243) as the artworks’ aura. The concept of the aura of the artwork is closely connected with the artwork’s authenticity. The authenticity of the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction entails the presence of the original in a particular temporal and spatial context. The main characteristic of the original is that no matter how close it is to the viewer by means of reproduction, it is still unapproachable (Benjamin, 1969, p. 243). The unapproachability of the source also converts into the cult value of an artwork. Therefore, if artworks in art museums gain additional accessibility by multisensory means, they lose a bit of their cult value.

The unapproachability of the original converts into the cult value of an artwork

The role of tactile sensations in the relationships between the art and the viewers is described by Walter Benjamin in terms of architecture. Benjamin brings up an example of a building that is “appropriated” by viewers in a twofold manner – by touch and sight (Benjamin, 1969, p.240). Visual contemplation of a building or an artwork requires concentrated attention. The opposite of attention to Walter Benjamin is a distraction from the habitually done tactile appropriation of architectural forms. It is possible to say that in terms of Benjamin multisensory exhibitions are similar to architecture – the viewers are partially distracted by the tactile “habitual” appropriation of the artworks via their 3D replicas, so their attention to the original paintings is in the less concentrated form than it can be in the visual-only exhibitions.

Benjamin saw the relation of concentration/distraction states of viewers to the absorption of an artwork by a collectivity. “A man who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it. He enters into this work of art...while distracted mass absorbs the work of art" (Benjamin, 1969, p. 239). The notion of absorption here can be interpreted as a kind of “habitual learning” (Strong, 2014, p. 168), the interiorization of the artwork on the whole.

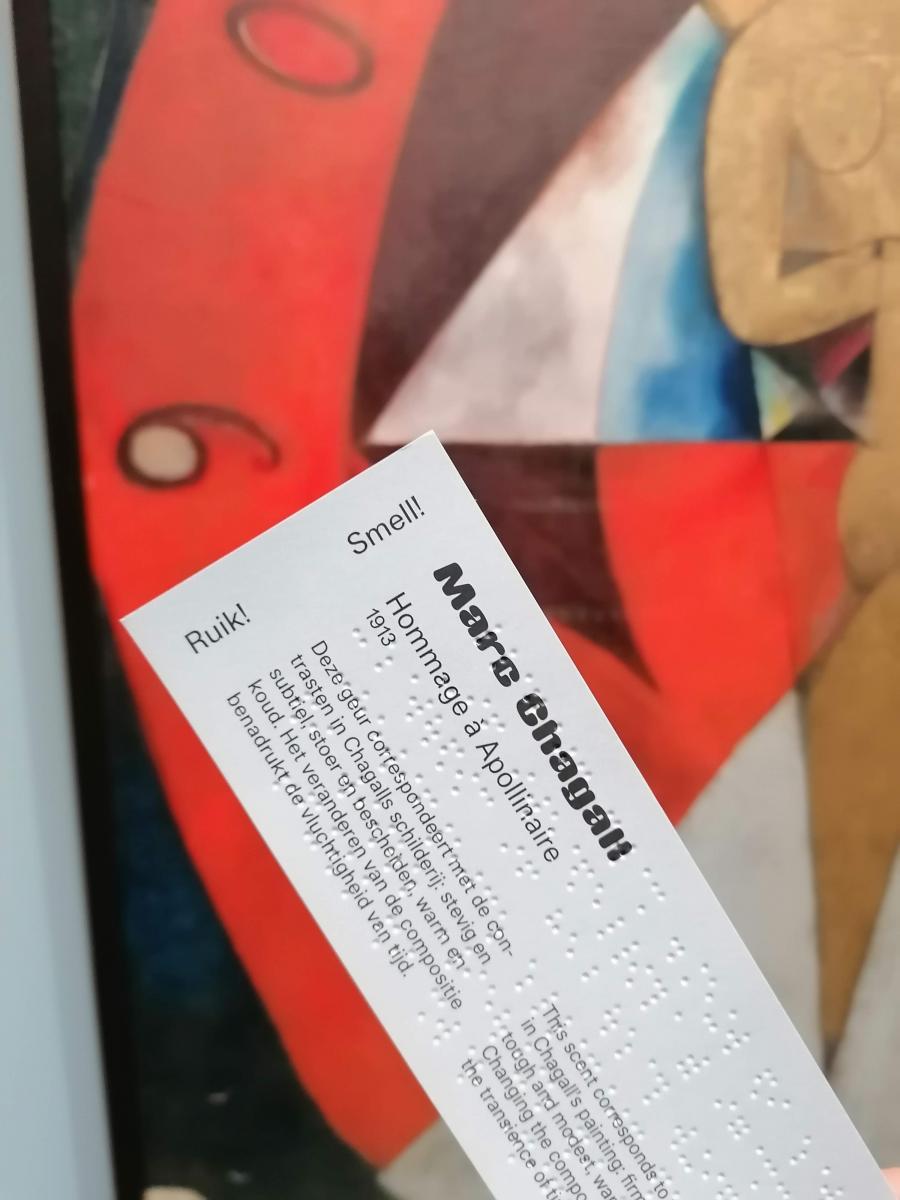

A tactile relief of the original artwork 'Homage to Apollinaire' by Marc Chagall

Intimate Experience

Whereas the possibility to “absorb” a painting in a multisensory exhibition comes with a decrease in its cult value, the interaction with the artwork becomes more intimate. As Axel and Feldman state, “a multisensory experience of artwork allows for visceral intimacy in ways that sometimes seem forgotten in today’s museum" (2014, p. 351). The seventeenth- and the eighteenth-century museum was where visitors could touch the collection and have an “intimate exchange” with the exhibits (Levent & McRainey, 2014, p. 76). Modern museums are experiencing “a sensory turn” (Tzortzi, 2017, p. 491) and are becoming “increasingly engaged with embodied, sensory and emotive forms of knowledge, and personal experience has become paramount” (Tzortzi, 2017, p. 491).

Olfactory art “engages visitors intimately,” unlike visual artwork, which is always separated from the spectators

The intimate atmosphere of the multisensory collection in the Van Abbemuseum is created with sensory tools, one of which is scents that accompany selected artworks. Olfactory art “engages visitors intimately,” unlike visual artwork, which is always separated from the spectators (Drobnik, 2014, p. 189). In the Van Abbemuseum, viewers are free to choose if they want to experience the olfactory features of selected paintings because their accompanying scents are not dispersed into the air. Instead, visitors can use the cards with the fragrance composition on them, which contributes to the individuality and intimacy of the experience.

A scent card for 'Homage to Apollinaire' by Marc Chagall

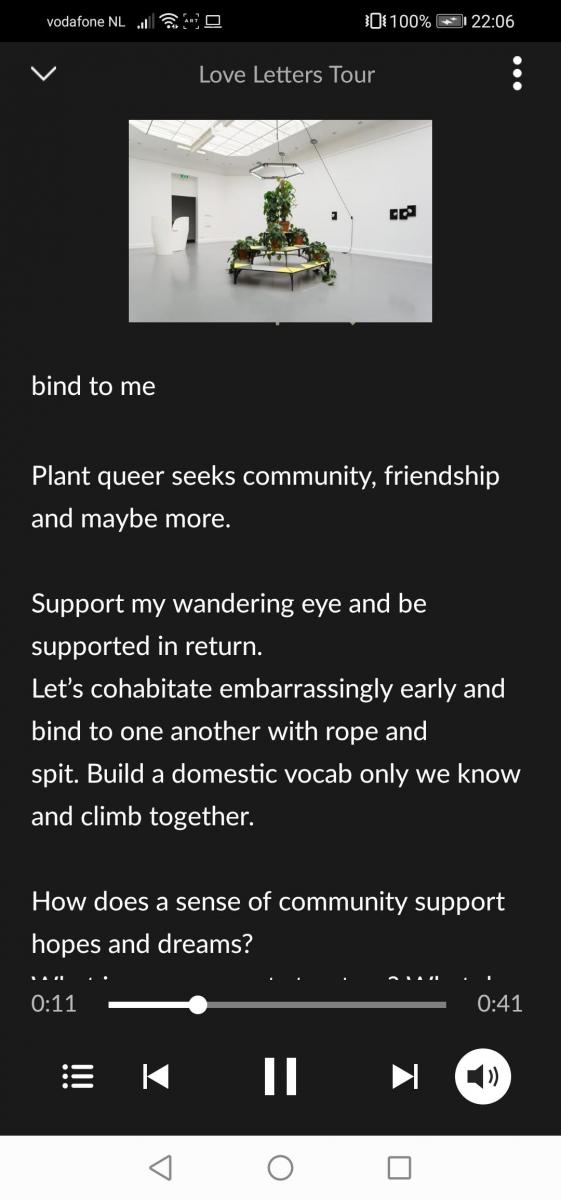

Intimacy is a two-way street, so visitors of the Van Abbemuseum can join the conversations about the featured artworks by responding to the poetic dating ads written on behalf of the artworks and posted in the Smartify app.

A “dating ad” posted by the artwork “À Bras Le Corps - with Philodendron” by Céline Condorelli

One of the dating ads belongs to a sculpture by Céline Condorelli, “À Bras Le Corps - with Philodendron.” This art object looks like a park bench with a plant on the top and symbolizes meaningful conversations that people can start in public spaces like museums. The artwork has an ambient olfactory feature to make the atmosphere around it more intimate and to aid the conversations of the visitors, who are encouraged to sit on the sculpture like on a regular bench.

Conclusion

The case of the collection of Delinking and Relinking in the Van Abbemuseum demonstrates how the multisensory design of an exhibition challenges the concept of the artwork’s aura and allows visitors to connect with the art at a more intimate level. Authentic artworks in the multisensory exhibition are accompanied by touch replicas and musical and olfactory interpretations of the originals, which makes the works of art more accessible to the viewers but at the same time partially stripped of their cult value or “aura.” At the same time, the increased accessibility of artworks changes the way of their viewing them. The combination of visual contemplation and tactile reception of the artworks done via their touch replicas requires a less concentrated form of the (sighted) visitors’ attention, which enables them to “absorb” or internalize the artwork on the whole in an easier way. However, enabling the visitors to “absorb” artworks is not the only function of sensory tools. They also help to establish an intimate connection between the visitors and the artworks, providing the viewers with a more personal or embodied experience.

At present, embodied experience is receding as multiple spheres of our lives are becoming increasingly mediated through digital networking technologies. The coronavirus pandemic forced art museums whose work had not been customarily done online to convert the entire exhibitions into virtual tours (for example, Face to face with Gustav Klimt” in the Van Abbemuseum). A multisensory collection in an art museum in 2021 looks like a response to the anti-coronavirus measures that had been applied during the pandemic period and as an attempt to address the deficiency of embodied sensory experience existing in our society.

References

Axel E., & Feldman, K. (2014). “Conclusion: Multisensory Art Museums and the Experience of Interconnection. Elisabeth Axel and Kaywin Feldman in conversation with artists and curators.” In The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space, edited by N. Levent, and A. Pascual-Leone, 351–360. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Benjamin, W. (1969). "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." In Hannah Arendt (ed.) Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, pp. 217-252. New York: Schocken Books.

Drobnik, J. (2014). “The Museum as Smellscape.” In The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space, edited by N. Levent, and A. Pascual-Leone, 177–196. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Levent, N., & McRainey, D. L. (2014). “Touch and Narrative in Art and History Museums.” In The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space, edited by N. Levent, and A. Pascual-Leone, 61–84. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Pallasmaa, J. (2014). “Museum as an Embodied Experience.” In The Multisensory Museum: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space, edited by N. Levent, and A. Pascual-Leone, 239–250. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Strong, R. C. (2014). “Habit, Distraction, Absorption: Reconsidering Walter Benjamin and the Relation of Architecture to Film.” in The Missed Encounter of Radical Philosophy with Architecture, edited by Nadir Lahiji, Bloomsbery Academic., pp. 163-181.

Tzortzi, K. (2017). “Museum architectures for embodied experience.” Museum Management and Curatorship, 32:5, 491-508.