“Netflix finally gets me”: algorithmic imaginary of Netflix users

Netflix algorithms have been creating a personalized feed for each user of the platform since 2015 (Brincker, 2021). According to Netflix Personalization & Search page, the platform currently personalizes users’ experiences in three ways: (1) the suggested videos and their ranking, (2) the way videos are organized into rows and pages, and (3) the artwork displayed. Netflix claims that its personified content “can fit the member’s current mood and context, and surfaces some surprises that bring unexpected joy.” However, sometimes personalized content makes users of the platform experience emotions other than joy. Maria Brinker (2021) describes an incident with a misleading personalized artwork that happened in 2018. The personalized cover art of the film “Like Father” came in two versions: featuring only white cast members and only black cast members. The cover image with black actors was intended for the users interested in stories with Black protagonists but the targeted audience found the film disappointing. According to social media pushback following the release of “Like Father”, the black actors there "had may be a 10 cumulative minutes of screen time" (Brinker, 2021, p. 88), which posed a question of “false advertising or of being duped into watching” (Brinker, 2021, pp. 93).

Experience machine

Netflix is not just a conduit of digital media (Gillespie, 2018, p. 7) but a platform. Netflix connects the users with the digital content but at the same time moderates it (Gillespie, 2018, pp. 5-9). However, Netflix does not have affordances to connect users to each other, upload user-generated content, or post reviews, so in its case moderation takes the form of filtering or algorithmic personalization of the videos. Highlighting certain content algorithmically, Netflix serves as the “arbiter of taste” for the platform members.

Brinker describes the algorithmic content personalization on Netflix as a “filter bubble” (Pariser, 2011) – a “bubble” of past preferences where users are trapped in an “experience machine” (Nozik, 1974) – an imagined machine that could provide whatever pleasurable experiences we wanted. Brinker argues that the current forms of algorithmic personalization on Netflix "(1) create deceptive shared world illusions (2) remove or further retract what was previously shared world aspects (3) make it harder to tell if what we are seeing is personalized or not.” (Brinker, 2021, p. 94)

Another concern in terms of Netflix algorithmic personalization might be the low priority of the user’s agency to make their own cultural choices. According to Ted Striphas (2015), “human beings have been delegating the work of culture – the sorting, classifying and hierarchizing of people, places, objects and ideas – increasingly to computational processes”. Striphas argues that such a shift “significantly alters how the category culture has long been practiced, experienced and understood, giving rise to ‘algorithmic culture’” (p. 395). However, Striphas emphasizes that algorithmic culture is “not strictly computational” because algorithms join together the human and the nonhuman, the cultural and the computational (p. 408).

Highlighting certain content algorithmically, Netflix serves as the “arbiter of taste” for the platform members.

The aim of my essay is to investigate the human side of the algorithmic culture based on the case of Netflix. What do Netflix viewers feel towards personalization algorithms? Do Netflix users feel in control of their film choices? How do Netflix algorithms help to generate “the moods, affects and sensations” (Bucher, 2017, p. 32) of its viewers? In order to address these questions, I am going to use the concept of algorithmic imaginary, under which Taina Bucher understands “ways of thinking about what algorithms are, what they should be and how they function” (Bucher, 2017, p. 30).

Bucher explains that algorithms are not purely technical. Algorithms are designed by humans, and ordinary users interact with them on daily basis thus modifying the algorithms of the platforms (“machine learning”). According to Bucher, “algorithms are not just abstract computational processes; they also have the power to enact material realities by shaping social life to various degrees” (Bucher, 2017, p. 40) – that means that algorithms shape our cultural reality as well, for example, when Netflix personalizes our “Top picks” or cover art of the films. That is why Bucher argues that studying how algorithms make people feel is crucial if we want to understand “their social power” (Bucher, 2017, p. 30).

Twitter impressions

In order to gain an insight into the human side of the algorithms, I have gone to Twitter. The social media platform has millions of public profiles; its textual messages are not longer than 140 characters and it is possible to search for tweets using a platform-specific search engine. Bucher considers Twitter to be “a great tool for accessing ideas, sentiments and statements about almost anything, including algorithms” (Bucher, 2017, p. 32) Following Bucher’s methodology, I have collected tweets using a search “Netflix + algorithm” which people posted in December 2021 and January 2022. This is the period of winter holidays – the time when people locate most of their activities indoors and are quite likely to use streaming services for entertainment.

I found 71 tweets on the topic of Netflix algorithms and divided them into five categories: (1) tweets that express anxiety about “ruining” one’s algorithm, (2) tweets that express surprise at the sight of strange recommendations, (3) tweets of gratitude to the algorithm after a particularly good recommendation, (4) tweets of dissatisfaction - usually a complaint about bad recommendations and suggestions on how Netflix should “fix” the algorithm, and (5) tweets -reflection on the work of algorithms. Unfortunately, my attempts to reach out to users who wrote the tweets in order to ask them interview questions (like it was done in Bucher’s research) kept failing, so eventually I took a decision to continue my study focusing on the analysis of the tweets.

“Don’t mess with my algorithm”

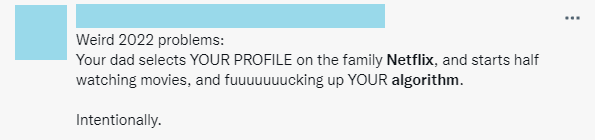

In this category of tweets (n=12) people refer to Netflix algorithmic personalization as an object of value. The authors of the tweets mentioned deliberately “training” their Netflix algorithm to teach it how to recommend content that leaves up to their expectations. Purposeful training of algorithm involves self-discipline as well: sometimes users half-jokingly confess that they are refraining from watching a holiday comedy because it might be bad for their Netflix algorithm. Most of the tweets in the category, however, express anxiety about something or someone “messing with the algorithm” and a desire to protect their personalized environment from intruders. Those tweets are addressed to family members, exes and even to complete strangers who have supposedly hacked into the author’s Netflix account and are using it for free.

Figure 1: Example tweet of the category “Don’t mess with my algorithm”

Netflix personalization is not only valuable to individuals as a form of immaterial possession but it is also perceived as an extension of users’ identities and an indication of their taste. Despite the fact that Netflix does not make information about members’ film taste socially sharable, some users still find it important to keep their personally “trained” Netflix algorithm in order as if their profile might suddenly be seen publicly.

“Netflix algorithm just trolling now”

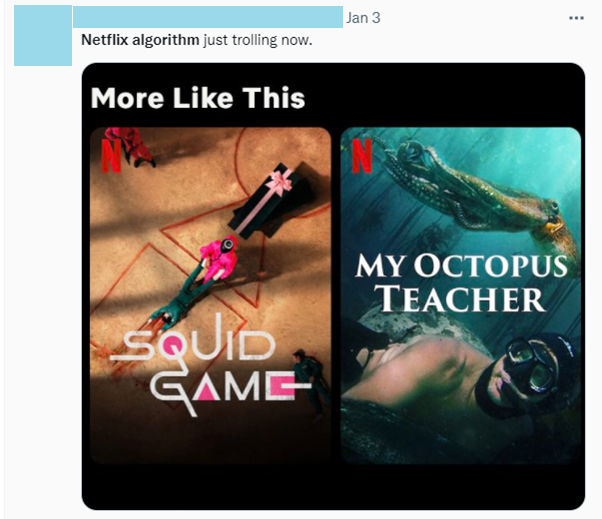

The second group of tweets (n=7) in our study are the posts about odd or funny Netflix recommendations. Such tweets usually consist of a screenshot of the recommendation and an ironic textual commentary. Users express surprise bordering on indignation when they find a totally out-of-place recommendation in their “More Like This” section. Tweets of this kind often personify the Netflix algorithm representing it as some kind of a mischievous being.

Figure 2: Example tweet of the category “Netflix algorithm just trolling now”

“The Netflix algorithm finally gets me”

This category of tweets (n=17) is dedicated to the positive experience with Netflix personalization. Users express satisfaction with the recommended content and gratitude to the algorithm that brought these recommendations to them. Some users are happy with the entire type of content that they have discovered thanks to Netflix (e.g. K-dramas), some others appreciate that the algorithm has “finally” suggested at least one title that lives up to their standards. In any case, users post their tweets of gratitude when Netflix manages to connect with them emotionally on a very personal level. For example, one user found it very touching when in her recommendations she saw a film, which was “formative” for her. Tweets of gratitude indicate that their authors tend to personify the algorithm attributing it human traits. Users assume that the algorithm “knows” them like an old friend and deserves to receive a thank you for a good recommendation.

“Fix your algorithm!”

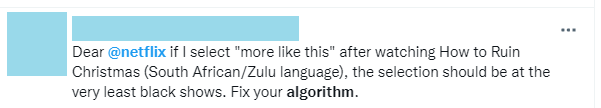

This group of tweets (n=16) is almost the same size as the one about positive experiences with Netflix personalization (n=17). However, tweets of gratitude to the algorithm are homogeneous in structure and have the same reason behind them – a particularly good personalized recommendation of content. Tweets of dissatisfaction, on the other hand, are very diverse: some users complain about poor recommendations, some others say that algorithm spoils the series they are watching by showing cover art from new seasons, someone else is annoyed because algorithms do not give priority to the shows they are watching these days.

Figure 3: Example of tweet of the category “Fix your algorithm!”

In addition to a complaint, some of the tweets contain a suggestion on how to “fix” the algorithm: for example, apply better genre classification to avoid mismatches, let the “Currently watching” shows pop up on the homepage, normalize “returning “0” search results” when the content is not available instead of a list of unrelated titles. Quite often tweets of dissatisfaction with algorithms are addressed to @netflix account on Twitter.

“What does the algorithm think about you?”

The last category of tweets (n=19) consists of the posts of reflection about the work of Netflix algorithms. In these tweets, people are either asking questions on how Netflix algorithms provide them with recommendations or post their own thoughts about algorithmic personalization (e.g. “Netflix algorithm is about frequency and rating, not about quality of content”). Some users (probably, more tech-savvy ones) analyse elements of personalization, such as cover art, and assess the work of the algorithm (“The Netflix thumbnail algorithm knows how to get me watch something. It’s not going to work in this case but A+ for efforts.”). Most of the reflection tweets, however, criticize the personalization technology and provide tips on how to cheat Netflix algorithms, which include “search manually”, “add weird ass sh*t to watchlists”, “watch as great a variety as you can” and, finally, pay attention to “the world outside of Netflix”.

Algorithms do things to people, people do things to algorithms

The analysis of 71 tweets on the topic of Netflix algorithms has shown that their authors express a whole range of different emotions, feelings, and sensations associated with Netflix algorithms. The study has demonstrated that members of the Netflix platform are emotionally attached to their accounts’ personalization. Users, who purposefully “train” their Netflix algorithms, are aware of their role as co-creator of the algorithm and their agency to tailor their Netflix experience. A “trained” algorithm is perceived as a valuable possession – something that should be cherished and protected from intrusion.

Many users also view their Netflix personalization as an indicator of their cultural taste and an extension of their identity– in this way algorithms influence people’s sense of self. Poor recommendations, odd suggestions, and wrong content genre attribution surprise the users, entertain them, or arouse their indignation. The tweets about Netflix algorithmic oddities with a screenshot of a recommendation are usually accompanied by an ironic remarque.

Users assume that the algorithm “knows” them like an old friend and deserves to receive a thank you for a good recommendation

Many tweets that took part in this study are an expression of joy that a good algorithmic recommendation provided to the users. However, within our selection the number of tweets expressing disappointment with algorithmic personalization is almost equal to the number of satisfaction tweets. Users vent their anger and frustrations with Netflix algorithms and express their opinions on how the platform should fix its algorithms.

Lastly, there is a relatively big number of tweets by tech-savvy authors who are trying to make sense of the algorithms: they inquire how Netflix algorithms work, assess how successful their algorithmic personalization is, and speculate about future changes in the algorithm.

Netflix personalization algorithms evoke a wide range of feelings in the platform's users. These feelings make people adjust their practices of using the platform, hence changing the algorithms, and algorithms, in their turn, make an impact on users’ behaviour. It is a recursive loop, in which “algorithms certainly do things to people, people also do things to algorithms” (Bucher, 2017, p. 42), and that is why it is important to study not only the technical side of this force-relation, but the human side as well.

References

Brincker, M. (2021). Disoriented and Alone in the “Experience Machine” – On Netflix, Shared World Deceptions and the Consequences of Deepening Algorithmic Personalization. SATS, 22(1), 75-96.

Bucher, T. (2017) The algorithmic imaginary: exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms, Information, Communication & Society, 20:1, 30-44

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, state, and utopia. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web is Changing What We Read and How We Think. New York: Penguin.

Striphas, T. (2015). Algorithmic culture. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4–5), 395–412.

Netflix. Personalization & Search. Helping members discover content they'll love