The Notre-Dame fire and digital vigilantism

On April 15, 2019, one of France’s most famous landmarks was the victim of a major fire. The Notre-Dame cathedral's spire and most of its roof were destroyed and its upper walls severely damaged. President Emmanuel Macron described it as a “terrible tragedy”, and hopes that the cathedral would be restored by 2024. The fire was one of the major events of 2019 that shocked people all over the world. Many online live streams kept everyone up-to-date, and #NotreDameFire trended on Twitter. Donations were made and promised to restore the cathedral, but not everyone responded to this with gratitude. How did this global tragedy provoke the callout of billionaires? And what did social media have to do with it? In this essay, I will analyze the response of the audience to the French tragedy, how they interacted, and the role that social media played in this.

How it happened

The Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral was originally built between 1163 and 1345. The cathedral’s spire has been rebuilt multiple times, most recently in the 19th century. At the time of the fire in 2019, the spire was again undergoing renovation. A lot of attention had been given to the risk of a fire at the cathedral. Fire drills were conducted regularly, and fire wardens checked conditions beneath the roof three times a day. But on April 15, a fire broke out in the attic beneath the cathedral’s roof. Before the guards had climbed all three hundred steps to the attic, the fire has already spread.

Most of the wood and metal roof and the spire of the cathedral were destroyed, and only one-third of the roof remained. The cathedral’s artworks, religious relics, and other treasures were mostly saved. Some had been removed in preparation for the renovations, while others were mostly held in the adjoining sacristy, which the fire did not reach.

Through the 24 hours following the fire, people gathered along the Seine to hold vigils, sing, and pray. Notre-Dame is a cherished place in Paris, and the grief was felt throughout the entire country. The cathedral is not just the most popular tourist site in Western Europe - since its completion, it has remained an active place of worship. About 2,000 services are held in the Notre-Dame cathedral every year. Macron, the French president, expressed the shock of the “whole nation” at the fire.

Citizen witnessing and digital vigilantism

The shocking event was followed by the whole world. News broadcasts and social media platforms were all focused on the #NotreDameFire. Many online interactions started through videos and photos that people took of the event. More often than not these days, the first person to be at the scene of a crisis with a camera is an ordinary citizen. With our easy-to-carry digital devices and the ease with which we can upload and share imagery on social networking sites, survivors, bystanders, first-responders and activists feel compelled to bear witness. As an average citizen-photojournalist, you can be on the spot to capture the moment and publish it immediately. This type of first-person documentation gives audiences vivid and personalized insights into what happened.

In recent years, the term ‘media witnessing’ has emerged as a way to describe how digital technologies are transforming our capacity to bear witness. It refers to the witnessing performed in, by, and through media. We are provided with more and more information about events that have no direct influence on our own lives, yet they have an emotional effect upon us because of their representation and our consequent witnessing of them.

Figure 1: Live footage of the #NotreDameFire on Twitter

Modern audiences want to understand what people who witnessed the event experienced; they want to see what breaking news looks like through the eyes of those who saw it. Twitter is full of videos and images like the figure above. Audiences on Twitter are captivated by the live footage from all different angles. By witnessing the live footage captured by others, millions of people can be shaken and disturbed to the point that they are prepared to donate money or to assist someone in danger.

The “French tragedy” at Notre-Dame has definitely led to many donations. Four days after the fire, donors had already pledged €850 million to rebuild the 850-year-old monument. These include two of France’s top culture-minded billionaire families, the Pinaults and the Arnaults. However Apple chief Tim Cook, Walt Disney Company, and video game maker Ubisoft were also among the donors. Indeed, in a country that has had many Saturdays of Yellow Vest protests - protesting, in part, income inequality - the backlash to such spontaneous largesse is logical.

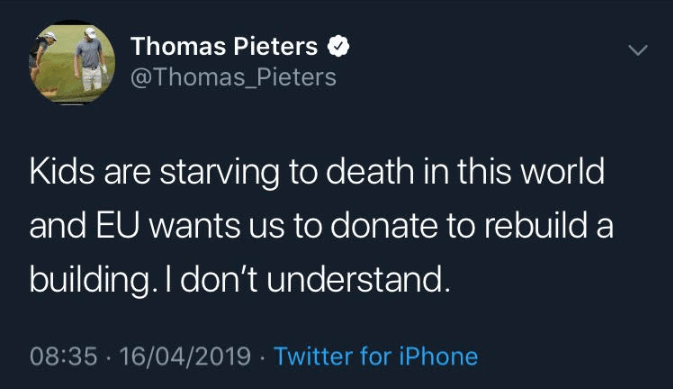

Figure 2: Ryder Cup star Thomas Pieters' now deleted Tweet

Many people commented on the large sum of money that was pledged to rebuild Notre-Dame. American author Kristan Higgins tweeted: “…Donate to help Puerto Rico recover. Donate to get the people of Flint clean water. Donate to get kids out of cages. Jesus didn’t care about stained glass. He cared about humans.” The water crisis in Flint, Michigan has lasted over four years. According to the NRDC, a sum of $97 million is needed to pay for repairs to the water supply. This was proposed in 2017, and yet little had been done to reach that goal. Other criticisms were aimed at donors for not paying their fair share in taxes and thus not giving the French government the opportunity to repair Notre-Dame itself. Witnessing the tragedy of Notre-Dame burning did not bring synergy, rather people formed different views and divergent opinions on how money should be spent. Because the live citizen footage brought so much visibility and emotion to the event, it became a common ground for people to incorporate social discussions of different issues like income equality.

These days, citizens' use of ubiquitous and domesticated technologies enables a parallel form of criminal justice. This is called digital vigilantism. Digital vigilantism is a process in which citizens are collectively offended by other citizen activity and coordinate retaliation on mobile devices and social platforms. There are various practices of digital vigilantism: hacking, calling out, trolling, doxing (publicly sharing personal and private information about an individual), and human flesh search (online participants find demographic and geographic information about individuals deemed deviant). In the case of the Notre-Dame fire, the most visible form of digital vigilantism is the “callout”: identifying and confronting toxic or inappropriate behaviors. It is intended to highlight behaviors without necessarily bringing focus to one individual. With the backlash to the Notre-Dame donations, the donors were called out by celebrities and “ordinary” citizens on multiple social media platforms. According to many people online, the money could have been used for more urgent issues in France and across the globe.

But why do people actually mourn the loss of buildings like Notre-Dame? Parisians have spoken about how the fire has made them think about identity, shared culture, and memory. The flood of personal statements of grief and loss and media coverage was exceptional. Notre-Dame de Paris is one of the top three sites that attract visitors to Paris, so tourists with first-hand experience of the Cathedral might have memories with an emotional value connected to it. But the fire may bring up emotions even for those who do not have a direct personal experience of the place. They might resonate with its symbolism, history, art, architecture, or the role it has had in Christianity.

Therefore, digital vigilantism also has its hazards. Vigilantes may have the same end goal in mind as governments, but private actors may lack the skills and training that government agencies require. Even though some vigilantes are highly skilled, they operate outside of the legal system. There is no “quality control” mechanism to assure a minimum level of preparedness. Another hazard is the true motives of vigilantes. The vigilantes, in this case, might just aim to insult and offend any of the donors or billionaire families of France.

Opinions on the large donations made to repair the Notre-Dame are therefore differ widely from each other. Some see the donations as a sign of hope and healing, while others see it as a sign that we need to change our priorities.

How social media enables vigilante justice

Through networking platforms and social media, the whole world was able to share their thoughts on the Notre-Dame fire. Vigilante justice, where ordinary people decide to take the law into their own hands, has become a larger-scale activity since the founding of social media platforms. The open nature of the World Wide Web has led to the founding of platforms that focus on interactivity and participation. Kaplan & Haenlein (2010) define social media as “a group of internet-based applications enabling to create and share user-generated content.” This user-generated content includes uploading posts, sharing other people’s material, and commenting on others' posts. Social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter, as well as user-generated content sites, including YouTube and Flickr, became “the core of a host of web-based applications that together formed an expansive ecosystem of connective media” (van Dijck & Poell, 2013).

Law enforcement has a public nature and can be an easy topic for discussion. “To the community, law enforcement can be fascinating and contentious. It involves drama, intrigue, and excitement that society finds captivating. The number of crime dramas on television and in theatres validates this. People tend to get involved” (Waters, 2012). Even though the Notre-Dame fire was not a true crime, it was still a drama that a wide audience focused on. The development of social media has made it easier and safer for people to voice their opinion online: they can stay anonymous and safe within their own homes, and it is easy to do. Anyone can post almost anything online, with little to no fear of repercussions.

Social media logics have contributed to the way that news about the Notre-Dame fire was shared. Social media logic refers to the processes, principles, and practices through which these platforms process information, news, and communication. Van Dijck and Poell (2013) described four main elements of this social media logic: programmability, popularity, connectivity, and datafication.

Programmability refers to “the ability of a central agency to manipulate content in order to define the audience’s watching experience as a continuous flow” (van Dijck & Poell, 2013). In social media logics, there is two-way traffic between users and programmers. On sites like Twitter or Reddit, users post content and steer information streams, while the sites’ owners may tweak their platforms’ algorithms and interfaces to influence data traffic. The social media platform can trigger and steer users’ contributions, while users may in turn influence the flow of communication and information activated by such a platform. Due to this two-way nature of online traffic, programmability has serious consequences for both “platformed” society and social activities mitigated by social institutions. It influences the way that news gets shared, and therefore also the way that the news about the Notre-Dame fire gets shared.

The second element of social media logic is popularity. Mass media can shape public opinion by filtering out influential voices and assigning some expressions more weight. In the early days of social media platforms, they held the promise of being more democratic than mass media in the sense that all users could equally participate and contribute content (Van Dijck & Poell, 2013). However, through the years platforms like Facebook and Twitter have developed great techniques for filtering popular items and influential people. Twitter’s Trending Topics feature enables users to boost certain topics or news items, and Retweets are a tool to widely endorse a tweet. But Twitter also actively pushes Promoted Tweets: they are paid for by companies and personalized via algorithms to fit specific timelines. Influential Twitter users are slowly finding their way into the star-system of mass media alongside other celebrities. TV shows increasingly define the “news of the day” through Twitter trends or by looking at Facebook discussions. Tweets are used as quotes, giving Twitter a powerful function as a public relations tool. The Notre-Dame fire was discussed on TV and news sites, but social media platforms also played a big role in sharing information about the event. News spread because #NotreDameFire was trending all over Twitter. This is not only due to what people posted but also Twitter's algorithm.

When social media platforms emerged in the early 2000s, their primary goal seemed to be connectedness. However, this human connectedness can more accurately be described as connectivity, originally a hardware term. As stated by van Dijck and Poell (2013), "connectivity... refers to to the socio-technical affordance of networked platforms to connect content to user activities and advertisers." Unlike mass media, social media platforms seldom deal with geographically or demographically formed audiences. Instead, they mediate connections between individuals. They partly allow the formation of communities through users’ initiative and partly forge target audiences through automated group formation or personalized recommendations (Van Dijck & Poell, 2013). The recommendation culture grounded in automated connectivity is appreciated by some: they enjoy the service offered by platforms to connect them to like-minded people. Others, however, hate networked customization as a symbol of invaded privacy or exploited user information. This element can also influence the way that people receive news. If they create a bubble of connections around one specific interest, they might miss general and global news.

Datafication is the last element of social media logic. All platforms have their own strategies for predicting and repurposing user needs, while also nursing their equivalent of “real-timeness”. Both are grounded in the principle of datafication. What makes datafication crucial is its ability to add a real-time data dimension to mass media’s notion of liveness (Van Dijck & Poell, 2013). Social media data streams are increasingly used as real-time analytics to complement or replace traditional polls issued by news media. Police or law enforcement can also use this real-time data for surveillance purposes. Again, this principle has profound implications for the shaping of social traffic. Predictive analytics and real-time analytics are new tools in the struggle to prioritize certain values over others.

All these elements of social media logic contribute to the way we share news and what news gets shared. As social media users, we do not have complete power over what we see online and the platforms themselves often steer our interactions and with whom we get to interact. Our opinions might be influenced, including about the Notre-Dame fire. Do we feel empathy for the people who feel the loss, and are we grateful for the donations made? Or do we call out the people who prioritize a building over other environmental and societal issues? Social media platforms give us a voice, but they also shape our voice.

Conclusion

The Notre-Dame fire was a shock not only for the French but for people all over the world. Videos, hashtags, and live streams on social media platforms were viewed globally. Not only did the fire make an impact but the donations made for repairs became even more of a discussion point. Donors pledged over €850 million to repair the cathedral, but not everyone was full of gratitude. The great amount of money caused a backlash online, as some people believe that the donations would be better given to other causes. These interactions on social media were essential to the discussion of the Notre-Dame fire. Social media is a space for people to share their opinion, but users are not the only people with power on these platforms. The owners of these platforms have just as much influence on the content that is generated and shown, and therefore they also influence our opinions and views. There is no general answer to what is right and what is wrong in this case. Even though people would like to call out others for their behavior, there is no actual crime committed. But should the priority of donations be on a building instead of other people? It is a discussion that is still far away from reaching an actual answer.

References

Allan, S. (2016). Citizen witnesses. In Witschge, et al. (Eds), The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, SAGE Publications.

Baker, V. (2019, 17 April). The grief that comes from lost buildings. BBC, 2019.

Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53, 59-68.

Kosseff, J. The hazards of cyber-vigilantism. Computer Law & Security Review 32,4 (2016): 642-649.

Van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Media and Communication, 1(1), 2-14.