The Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong

Social movements in the digital age

This paper shows how a networked social movement led to effective communication, mobilization, identity awareness and gaining publicity during Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. It does so from a personal perspective.

As a Hongkonger, I personally experienced the Umbrella Movement which started in 2014, the historically largest social movement in Hong Kong in terms of duration, location and reach and also very much empowered by digital media.

Introduction

In the last few years, your Facebook news feed must have been clogged with videos about the Ice Bucket Challenge, news about the Arab Spring, rainbow icons for supporting the legalization of homosexual marriage in the US and, recently, French flag icons for supporting Paris and against terrorist attacks. Regardless of whether you are a digital migrant or a digital native in either the Western or Eastern Hemisphere, you have probably engaged in at least one social movement through the digital world. In the digital age, these social movements have certainly aroused and sparked political and social debates and further actions locally and internationally through the digital power of the Internet, social media and mobile media.

As a Hongkonger, I personally experienced the Umbrella Movement which started in 2014, the historically largest social movement in Hong Kong in terms of duration, location and reach and also very much empowered by digital media. In this paper, I will use the Umbrella Movement as a case study to illustrate how the digital world can empower people in social movements. I will also draw on my own experiences and observations during my engagement in the Umbrella Movement as a supporter, local and international communicator both offline and online, street occupier, observer and resource supplier to strengthen and widen the discussion.

The Umbrella Movement

The Umbrella Movement started as a spontaneous social movement for democratic development in Hong Kong in September 2014. In what follows, to introduce the Umbrella Movement, I will discuss the political and social background of Hong Kong, the background of the movement and how it evolved.

To begin with, the Umbrella Movement is related to the political and social history and context of Hong Kong. Hong Kong used to be a British colony, but since the handover of 1997 it is a city of China. According to the constitutional principle One Country, Two Systems, the Chinese Communist Government ensured Hong Kong will retain its own currency, legal and parliamentary systems (democratic institutions which have been developed since the British colonial period) and people's existing rights and freedoms for fifty years (Holliday, & Wong, 2003). However, critical voices have emerged in Hong Kong to protest against actions by the government which have been seen as prioritizing the interests of the Chinese Communist Government for instance through the spending of public funds for pro-China white elephant projects. At the same time, many citizens have expressed dissatisfaction and anger over the neo-liberal economic policies of the Hong Kong government which have been seen as producing new social inequalities in the society. Thus, already before the Umbrella Movement came into being, protests and social movements against the government policies already existed, and the unsolved political and social problems can be seen as the long-term causes for the appearance of the Umbrella Movement.

Moreover, there are some important short-term causes behind the development of the Umbrella Movement. In 2007, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of China (NPCSC) empowered Hong Kong to implement, through reforms, universal suffrage in view of the 2017 Hong Kong Chief Executive election and 2016 Legislative Council election (The Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, n.d.). Thus, since 2007 proposals regarding voting rights have been discussed in the Legislative Council. On June 22, 2014, an electronic Civil Referendum was conducted organized by the Secretariat of the ‘Occupy Central with Love and Peace’ (an organization active in the discussion regarding the electoral system in Hong Kong) As a result of the referendum, the organization launched a campaign demanding that the electoral reform should fulfill the international standards of universal suffrage, the rights to vote, to be elected and to nominate, and about 700,000 voters agreed that the Legislative Council should veto the government proposal if it would not satisfy international standards of universal suffrage allowing genuine choices by electors (Public Opinion Program, 2014). However, on August 31, 2014, the NPCSC decided to set a framework for the election reforms which limited the rights to vote, to be elected and to nominate (HKPOLITICS101, 2015). Considered a violation of the One Country, Two Systems, the decision caused reactions and disagreements in Hong Kong, also online. Several groups and organisations demanding a withdrawal of the decision by NPCSC and a universal suffrage also came into being.

Suppression in Hong Kong

On September 22 to 26, 2014, a university student strike was jointly organized by the Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS) and Scholarism, the pro-democracy student activist association in Hong Kong, to protest against NPCSC’s decision. They organized a series of open lectures in the Tamar Park, Tim Mei Avenue and the square outside the Legislative Council Complex in Admiralty, the commercial business district and the location of the Central Government Offices of Hong Kong (Yao, 2014). On the night of the 26th of September, led by Joshua Wong, the convener and founder of Scholarism, and the members of HKFS, hundreds of protesters gathered to reclaim the Civic Square which, originally a public space, had had fences built around it two months earlier (Bai, 2014). The Umbrella Movement thereby started with large-scale street occupations.

There are some other prominent aspects to the development of the Umbrella Movement. Firstly, conflicts between the protesters and police can be seen as a prelude to the Umbrella Movement. On September 28-29, the clearing and dispersing operation by the police caused more than a hundred thousand people to engage in the movement, as the violence by police officers towards civilians (e.g. tear gas, pepper spray and truncheons) was the most aggressive in the last 25 years in Hong Kong while the protesters did not have any weapons, and were mainly students who raised a lot of support and empathy for their cause as a consequence (South China Morning Post, 2014a). In the meanwhile, occupations were not only taking place in Admiralty anymore, but started to spread to two more districts, Causeway Bay and Mongkok, the famous busy areas of Hong Kong (South China Morning Post, 2014b). Other regions such as Yuen Long and Tsim Sha Tsui were also occupied, but the protesters were rapidly removed by the police after a few days. Thus, during the first week of the movement, it recorded over a hundred thousand people participating every night (Yao, 2014).

Secondly, the long-term occupations helped create a shared culture and symbols for the Umbrella Movement. For instance different organizations, installation artists, and musicians took part in different ways to support the movement. One significant example is the huge pro-democracy banner that was hung from the Lion Rock, a famous hill in Hong Kong which has been a symbol of the Hongkonger since the 1970s (Lo, So, & Tsang, 2014). At the same time, the aims of the Umbrella Movement became more diverse, from merely political ones demanding for the rescission of the NPCSC decision and achieving a real universal suffrage to advocating the improvement of social inequality in terms of housing, urban-rural development and different rights such as human rights, ethnic minority rights, gender equality and labor rights. Tensions between the parts of the population for and against the occupations thus emerged widely in the society, and the Hong Kong–Mainland conflict also appeared on different levels. The Umbrella Movement was ended on the 15th December, 2014, after 79 days of occupations. 955 people were arrested during the movement (Tam, 2014). Unfortunately for the movement, by mid-December it had failed to achieve its aims.

The unique attributes of networked and digital social movements

We can distinguish two types of social movement, the ‘traditional’ social movements and networked social movements. The term ‘networked social movement’ was suggested by Manuel Castells, a sociologist in the field of digital society and communication, and refers to social movements influenced by the digital world, the net and mobile communication (Castells, 2013). The attributes of a networked social movement are certainly different from the ones of social movements in the past, and the Umbrella Movement can be seen as a type of networked social movement. Sociologically, in the past social movements consisted of a collective of individuals who aimed at achieving some kinds of political and social change (Touraine, 1985). Although the traditional social movements and networked social movements both aim at achieving some kinds of political and social change, they are quite different in terms of their structure and forms of practice, or in other words, the Digital Age has transformed the social movement .

No digital force could create a social movement alone without an aim by, for and from people.

On the one hand, the structure of traditional social movements is hierarchical while the networked social movement has a matrix structure. Traditionally, a social movement is a leader-based movement that is led by political parties or politicians in a top-down approach (Howard, & Hussain, 2011). They usually already have a blueprint for an organized and systematic strategy before the social movement itself emerges, so the objectives of the traditional social movement would be relatively unitary and direct (Howard, & Hussain, 2011). Also in the case of earlier social movements in Hong Kong, the demonstrations were usually led by a political association that would organize to build a stage in a specific place as a starting point for gathering a mass of people. The participants would then follow the route of demonstration and leaders of the association systematically. The structures were thus certainly hierarchical.

However, in the digital age, the structure of networked social movement has transformed into a matrix structure. Specific political or social issues can be widely discussed and scale up quickly relying on digital infrastructures which empower basically everyone to engage with the topic easily. This more equal and liberal digital environment embraces a leaderless format, transforming the social movement from a leader-based structure into an issue-based structure with a bottom-up approach (Tufekci, 2014). The matrix structure could also be described as a network of networks. This refers to a core network of the social movement which is connected to lots of different internal and external networks in various associated fields existing both offline and online (Castells, 2013). Therefore, the matrix structure of the networked social movement is more decentralized which is quite different from the structure of traditional movements. Because of these two attributes, the goals of a networked social movement are more diverse. In the Umbrella Movement, the structure had involved some student leaders in the beginning, but the overall movement was still issue-based instead of a leader-based one and consisted of a network of networks.

On the other hand, the forms of practice of traditional social movements are relatively more limited while the networked social movement is relatively more autonomous. In the traditional social movement, although consisting of individuals, the direction of the practices of social movements were already restricted by the political party or politician initiating the movement. In the past, the initiator possessed more resources, experiences and information and, at the same time, treated the social movement as one of the stages for their long-term political struggles (Wu, 2014). In the digital age, the forms of practice in social movement has become more autonomous. Because of the decentralized structure of the networked social movement, the movement can develop largely in the digital world, while simultaneously the meaning of urban space is constructed by the empowered individuals participating. The space of practice for networked social movements is a hybrid of online and urban space, that is, the space of autonomy can be extensively explored and expanded (Castells, 2013). The occupations on Causeway Bay and Mongkok in Hong Kong are good examples of this. The Umbrella Movement was not only taking place in Admiralty, but the movement was rapidly inhabiting both online and urban spaces that created the space of autonomy.

Furthermore, the form of practice of networked social movements embraces an element of high reflexivity among the individuals. The advanced communication in the networked social movement empowers the individuals to share their inspirations and receive different new insights that simultaneously and consequently sustain the space of autonomy. The participants would thus autonomously reflect on their actions during the movement. In different stages of the Umbrella Movement, the participants also were highly reflexive regarding their theoretical and practical efforts that inspired various potential developing trends for the middle and late stages of the movement.

Symbol of Umbrella Movement

How did the digital world influence the Umbrella Movement?

When assessing the influence of the digital world on the Umbrella Movement, we have to understand that the digital world is a two-way interactive and contradictive force which can be used both for and against the protesters and can be both a positive and negative influence, rather than only exclusively a pro-protester and positive force. Thus, in the following parts I will try to discuss this from a dialectic perspective. This can also help explain how the digital world empowered the participants to operate the movement in four key areas: effective communication, organizing, identity construction and gaining public attention.

Digital media have empowered the participants in the Umbrella Movement to effectively communicate, organize, construct identity and gain public attention to their social movement

Effective Communication

Firstly, the digital world empowered the participants to communicate effectively in the Umbrella Movement. Information and communication technologies empower people to take actions in different fields at the same time and rapidly (Tufekci, 2014). This helped establish and sustain a mass and horizontal information delivery because of the created telepresence. In the Umbrella Movement, there were several YouTube live channels by different non-mainstream digital media like the PassionTimes, Hong Kong In-media and Social Record Channel, broadcasting live from the different occupied streets. For me personally, this also became one of the reasons for engaging in the movement. Around midnight on September 26th, 2014, I was watching the YouTube live broadcasting by the Social Record Channel in my dormitory. Once I had seen the students retake the Civic Square, I immediately shared the information with my dorm mates and afterwards went to the Square.

Apart from the organizational media contributing to the creation of telepresence, some participants taking the role of citizen journalists also contributes to it. This means that citizens can play an active role in the process of collecting, reporting and disseminating alternative, activist news and information outside mainstream media institutions which creates alternative sources of legitimacy apart from traditional or mainstream journalism (Radsch, 2013). In the Umbrella Movement, thousands of people would use their smartphones as their cameras to converge and report different real-time situations on different streets immediately on the Internet. One of the significant uses of digital media was to report different cases of the violent abuse by the police towards the activists. This alternative media contributed a lot by making visible otherwise marginalized events in the Umbrella Movement. Information and communication technologies thus worked exactly in breaking through the barriers to access visibility, as mentioned by Miller (2011:140). Moreover, digital media helped to gain publicity for and sustain communications within the movement. Due to their contributions to the movement, the number of followers on the Facebook Pages of PassionTimes, Hong Kong In-media and Social Record Channel also significantly increased (Wong, 2014). While mainstream media was more inclined to take a pro-government position, digital media remained a space for people to communicate and gain public attention for the movement. This role of digital media in gaining publicity will be discussed further below.

However, these empowering forms of communication also caused concerns regarding the reliability of sources. For example, Facebook’s ‘news feed’ feature rather algorithmically prioritizes ‘popular’ news instead of for instance the time of publication of a post. Thus, some users were trapped in believing old rumors, which had already been proven false. There were thousands of rumors circulating regarding the Umbrella Movement. An interesting example was that my friends and I had received a message spread on WhatsApp that the Chinese Communist Government would send the People's Liberation Army to suppress the movement with photos of tanks on the streets of Hong Kong given as evidence. This rumor was fortunately proven false by the Facebook groups specialised in checking the veracity of rumors. However, as Miller (2011:138) points out, ICT-enabled communication is instantaneous and largely uncontrollable. Hence, the rumor might have already had an influence on some people (considering) participating in the movement. But, on the other hand, it also led to the creation of ironic jokes. For instance, Andrew Fung, a top media official in Hong Kong, shared a fake photo spread on Facebook of a beaten police officer during the Umbrella Movement (Barber, 2014). This irony was also a reminder of the dual nature of digital tools.

Organizing

Secondly, in terms of organizing, digital media empowered the participants to mobilize, collaborate and cooperate in the Umbrella Movement. As mentioned above, the participants in the Umbrella movement used communication technology to help them come together in an ad-hoc manner to take an action and to achieve a specific aim. The ad-hoc method was used in quite diverse ways in different contexts, ranging from the use of mobile communication apps like WhatsApp and Firechat, to the use of Facebook (personal Facebook accounts, Facebook Pages, Events and Groups) and online forums, especially the Hong Kong Golden Forum, the most popular online forum for youth in Hong Kong.

Also in terms of mobilization, collective supportive actions and tactical actions were to a great extent empowered by communication technologies such as Facebook Groups or WhatsApp groups created for mobilizing regional supportive actions in different districts of Hong Kong. For example, I followed a campaign organized on the Hong Kong Golden Forum which suggested people to hang a yellow ribbon on street railings in their communities, and created a WhatsApp group for mobilizing my classmates to post banners encouraging the student protesters and supporting the occupations on the walls of the academic buildings of my home university. Apart from mobilizing for supportive actions, tactical actions were also similarly mobilized. Miller (2011:143) pointed out that ‘smart mobs’ behave intelligently through network links, mobile communication devices and pervasive computing, to perform a task in a form of collective intelligence. Communication technology enables smart mobs to be more practical. In the beginning of the occupation, several groups of smart mobs gathered to build roadblocks mainly out of rubbish bins, bricks and bamboo scaffoldings which all were easy to find in the streets in Hong Kong (Mingpao, 2014). With the help of mobile communication devices, they could immediately mobilize ‘helpers’ to set the roadblocks before the arrival of the police and they could also disperse rapidly. Their contribution helped successfully defend the occupied spaces by tactically outmaneuvering the clearing and dispersing operation of the police and attempting to expand the occupied areas.

Digital media was thus tactically important in the Umbrella Movement in terms of collective collaboration and cooperation However, inspiration drawn from digital gaming was also essential in empowering the participants in this respect. As mentioned above, people were mobilized for tactical actions like building roadblocks with the help of communication technologies. Similarly, the medium of computer game also empowered the participants to collaborate and cooperate smartly and smoothly. For example, the occupation in Admiralty was a good example of the cooperative and collaborative tactics of the students. They do not have any experience of military training but they used military type of tactics to cooperate (e.g. anti-sieging, temporary retreat and calling backup). Their history of playing multiplayer and real-time strategy games online and their sophisticated experiences of ‘death’ and ‘practice’ in the games inspired them to apply the tactical concepts in the offline world (Wong, 2014). They were already used to this form of cooperation and collaboration from their experience of playing multiplayer and real-time strategy games like League of Legends, the most popular online game among youth in Hong Kong. Now, inspired by their digital experiences, they were collaborating in the offline world with other smart mobs in allocating rubbish bins, bricks and bamboo scaffoldings and suggesting retreat routes as well as cooperating with other networks like the volunteers from emergency services and some student leaders.

There has also been skepticism regarding mobilizing and organizing relying on digital media. In the Umbrella Movement, to a great extent, digital media were instrumental in the mobilization of participants and organizing. However, according to Evgeny Morozov (2011), a writer focusing on the political and social implications of technology, talks about the ‘net delusion’ in relation to mobilizing through digital media. He discusses what he calls slacktivism, a pejorative term from the words ‘slacker’ and ‘activism’ (Morozov 2011), where participants feel good about themselves or satisfied by their online activities for a cause while in fact they have made a very small or nonexistent practical effect to support and contribute to a political or social issue. Here, the young generation, or, in other words, the digital natives, are especially targeted because they are said to sometimes underestimate the responsibility and accountability involved in engaging in a social movement. For instance, in the Umbrella Movement there was a petition against police violence organized by Evelyn Cheng, an ordinary Hongkonger. The Facebook Event created in relation to this petition showed that over 23000 people were engaging in it and about a thousand people were interested in this event. However, the actual number of participants is unknown and unclear. To a certain extent, the attitudes and forms of participating of the digital natives in social movements such as the Umbrella Movement can be characterized as slacktivism. There was also an unbalance between the mobilization in the digital and offline spheres. Therefore, the digital world was not always empowering Hongkongers to organize the Umbrella Movement effectively.

Identity Construction

Thirdly, the digital world empowered the participants to further construct a Hong Kong identity in the Umbrella Movement. The idea of ‘Hongkonger’ has been quite vague and fragmented. According to Ackbar Abbas (1997), a famous scholar in Hong Kong cultural studies, the narrative of Hong Kong identity was certainly limited before pre-colonial history and the idea was floating and loose. Before the colonization by the British, Hong Kong just had been either a kind of fishing village along the coast or a traditional Chinese wall village in the inland which were both formed by several separate indigenous communities (Abbas, 1997). During the colonial period, the British imperial culture strongly influenced Hong Kong and the main population consisted of refugees from China who were suffering from the political instability in the 1950s to 1970s and treated Hong Kong as a temporary stop only (Abbas, 1997). Therefore, Hong Kong was a hybrid of western and eastern migratory cultures and there was an absence of definite Hong Kong identity before the handover. The term Hongkonger, or Hong Kongese, was only added to the Oxford English Dictionary in March 2014 which proves that the conception of Hong Kong identity had been limited and vague in previous times (Lam, 2014).

After the handover, narratives have emerged about Hong Kong identity like the one by Ackbar Abbas. However, the discussion still mainly revolved around the political ideological dichotomy between Chinese or post-colonial British citizens, and the identity construction process was certainly dominated by the authorized narrative in a top-down approach. However, also due to the emergence of digital media, the rapid process of individualization has strengthened the discourse of Hong Kong identity. New media functionally allow people to interact with multiple persons simultaneously with the ability to individualize messages in the process of interaction (Chen, 2012). That is, all messages can be diversified, including those dealing with the discourse of Hong Kong identity. As Miller (2011:138) mentioned, the notion of identity politics has taken the place of traditional class-based politics in present-day social movements because information and communication technologies have highly increased individualistic interactions. For instance in the Umbrella Movement, everyone could contribute to its identity construction.

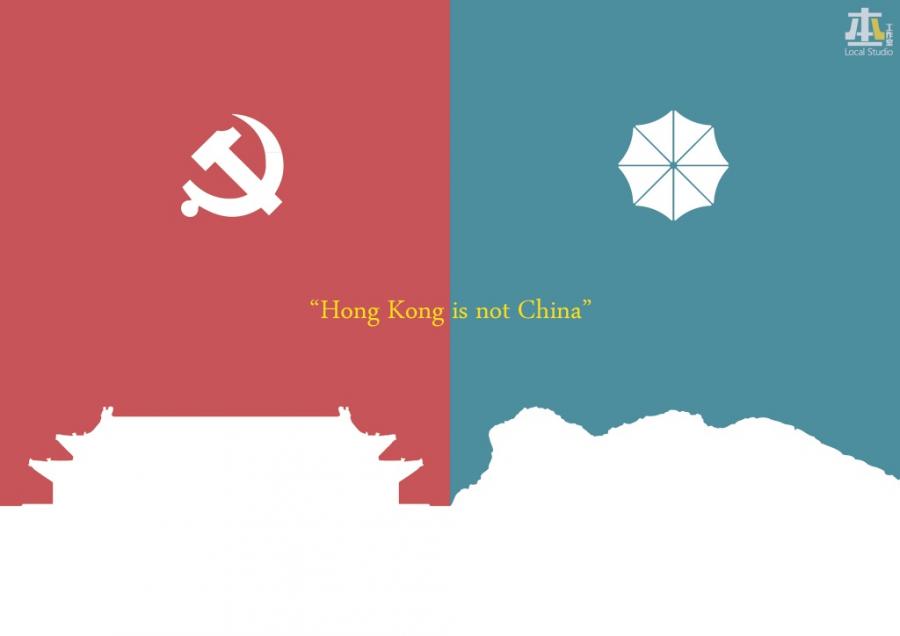

A Hong Kong identity has therefore been gradually created collectively. The narrative construction process has transformed from a political dichotomy with a top-down authorized approach into the plural and expanded cultural discourses of Hong Kong identity through a bottom-up approach in the digital world. The diversified narratives of Hong Kong identity has started to feature for instance Chineseness, Hong Kongness, pro-moderate democratic or pro-radical democratic positions, and ideas of both Asian and global citizenship. For example, the Hong Kong design studio Local Studio has created a collection of illustrations to sum up some of the differences between Mainland China and Hong Kong through their Facebook Page (Merelli, 2015). One of the illustrations was using the umbrella as a symbol to represent Hong Kong and to distinguish it from China. This kind of bottom-up contribution is part of the construction of a Hong Kong collective identity through digital means.

Hong Kong as different from China

However, the narratives of identity construction still often fall into a dichotomous subtyping. As mentioned above, apart from the political identity construction, Hong Kong identity is also culturally and socially constructed. At the beginning of the Umbrella Movement, students were using the yellow ribbon as the symbol of this movement and the practice further developed into a supportive campaign and taking of a political stance with people changing their Facebook profile pictures to feature a yellow ribbon. However, the pro-government, against-occupation side and those supporting the actions of the police also accordingly created the blue ribbon to be used as their symbol, also in Facebook profile pictures. The society was therefore divided as either yellow or blue dichotomously. This conflict has not been taking place only in the digital world, but also spread into offline life because the profile in a social network is no longer anonymous but reflective of one’s offline identity (Miller, 2011). There are, for instance, some cases featuring tensions between blue-ribbon employers and yellow-ribbon employees. This corresponds precisely with Miller’s (2011:168-172) suggestion that the profile in social networks is re-centering the offline identity rather than isolating online and offline identities from one another. Thus, this kind of dichotomous subtyping between blue and yellow ribbons creating divisions could be considered as a counter-productive aspect in the use of digital tools in the social movement.

Gaining Publicity

Lastly, digital media enabled the participants in the Umbrella Movement to gain local and international publicity. Social media in particular empowered the participants to establish and stimulate digital relationships and community to gain publicity. The correlation between social media use, especially Facebook, and political participation among Hong Kong tertiary-level students was certainly positive. According to professor Francis Lee (2015), a member of the Centre for Chinese Media and Comparative Communication Research, a forthcoming study,Comparative Research on Social Media and Civic Engagement among University Students in Greater China, highlighted that Facebook is the main social media among Hong Kong tertiary-level students. Moreover, the research found that having Facebook friends who were active in political and social movements, or commentators or journalists, highly correlated with their own participation in social movements because it influenced their information exposure and willingness to share social and political news on Facebook (Lee, 2015). As Miller (2011:190) pointed out regarding different types of virtual communities, a community of transaction facilitates the exchange of information, and a community of interest brings together participants who wish to interact about specific topics of interest to them. The Umbrella Movement was similarly empowered by digital communities such as these.

In addition, digital media helped the Umbrella Movement to gain international publicity. Information about the movement spread around the world with the help of the Internet, and the movement received a lot of international support. For example,the collective art project Stand by You: 'Add Oil' Machine (‘add oil’ 加油 is a term of encouragement in Chinese) aimed to display supportive messages to the protesters. Supporters from other countries or regions could send messages through the project website which in turn were projected onto the wall of the Central Government Complex in Hong Kong. They received altogether over 30,000 messages from about 70 countries (Keeps, 2014). "Anonymous", the famous hacktivist collective, also organized a cyber warfare operation, Operation HongKong, to contribute to the protesting by the Umbrella Movement. They hijacked governmental websites and unleashed distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks (Blum, 2014). The participation of Anonymous also contributed to gaining international exposure for publicity.

However, the international publicity gained was also demonized as the intervention of western powers by some pro-Chinese government media that consequently lost support. Privacy violations and cyber bullying also appeared in connection to the Umbrella Movement. For instance, there were some violent cases of abuse involving the police and opposite-side participants which caused a lot of people to express their anger online. Doxing, an Internet-based practice of researching and publishing personally identifiable information about an individual that aims to threaten, embarrass, harass, and humiliate the individual (Norris, 2012), was taking place. There was, for instance, an ironic case where a pro-movement participant was doxed by others who misunderstood him as an ‘enemy’ and published private details about him, including his name, school and details regarding his Facebook account (Yu, & Cheung, 2014). This created a small wave of cyber bullying against him. This intentionally (from the pro-movement point of view) ‘virtuous’ privacy violation can be considered as the flipside of being able to achieve publicity through digital media.

Future projection

Future social movements both in Hong Kong and elsewhere will probably in one way or another experience specific issues related to the use of digital media. On the one hand, governments will pay more attention to the digital world in order to maintain surveillance. New forms of censorship may be established in order to control the free flow of information but it seems hard to effectively censor the digital world. Social movements will also be reproduced as popular culture. Social movements have transformed, and new cultures would correspondingly be created to help sustain the struggle for the aims of the social movement. Different artistic and cultural forms have also been created within the Umbrella Movement.

Conclusion

In short, this paper did not engage with the pointless question of 'did the digital world create the revolution?’ because no digital force could create a social movement alone without an aim by, for and from people. Instead, the argument of this paper is simple: digital media have empowered the participants in the Umbrella Movement to effectively communicate, organize, construct identity and gain public attention to their social movement. The digital world is both interactive and contradictory, comprising both positive and negative aspects and enabling both positive and negative uses. However, the Umbrella Movement was empowered by the decentralized digital world that provides space of autonomy to engage in and contribute to the struggle both offline and online, interactively and interrelatedly. It seems that in our current digital age, the dividing lines in struggles regarding social movements between for and against sides are no longer created by age and generational differences only, but also by differences in digital skills and abilities.

References

Abbas, A. (1997) Hong Kong Culture and the Politics of Disappearance. Hong Kong: HKU Press, Excerpts.

Bai, L. (2014, September 27). Students regained the Citizens' Square, police forced to disperse and Joshua Wong was arrested. Apple Daily.

Barber, E. (2014, October 16). Hong Kong’s top media official shared a fake photo of a beaten cop. Time.

Blum, J. (2014, October 2). 'Anonymous' hacker group declares cyber war on Hong Kong government, police. South China Morning Post.

Castells, M. (2013). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. John Wiley & Sons.

Chen, G. M. (2012). The impact of new media on intercultural communication in global context. China Media Research, 8(2) 1-10.

HKPOLITICS101. (2015, March 01). Hong Kong political reform (4) - National People's Congress 831 decision. Inmediahk.

Holliday, I., & Wong, L. (2003). Social policy under one country, two systems: institutional dynamics in China and Hong Kong since 1997. Public Administration Review, 63(3), 269-282.

Howard, P. N., & Hussain, M. M. (2011). The role of digital media. Journal of democracy, 22(3), 35-48.

Keeps, D. (2014, November 29). Peter Gabriel, Pussy Riot Show Support for Hong Kong Protestors. Rollingstone.

Lam, J. (2014, March 19). 'Hongkonger' makes it to world stage with place in the Oxford English Dictionary. South China Morning Post.

Lee, F. (2015, January 23). The foundation of social network Social media and networked social movement. Pentoy.

Lo, C., So, S., & Tsang, E. (2014, October 23). Pro-democracy banner hung from Lion Rock has officials scrambling. South China Morning Post.

Merelli, A. (2015, July 1). These illustrations show how different Hong Kong thinks it is from mainland China. Quartz.

Miller, V. (2011). Understanding digital culture. Sage Publications.

Mingpao. (2014, October 14). Making roadblocks by bamboo scaffolding on the roads, construction workers help to build defenses by the building materials waste. Mingpao.

Morozov, E. (2012). The net delusion: The dark side of Internet freedom. Public affairs.

Norris, I. N. (2012). Mitigating the effects of doxing (Doctoral dissertation, Utica College).

Public Opinion Program. (2014). Results of “6.22 Civil Referendum”. The University of Hong Kong.

Radsch, C. C. (2013). The Revolutions will be Blogged: Cyberactivism and the 4th Estate in Egypt. Unpublished doctoral disseration). American University, Washington, DC.

South China Morning Post. (2014a, September 28). Police fired tear gas and baton charge thousands of Occupy Central protesters. South China Morning Post.

South China Morning Post. (2014b, September 28). Occupy Central - The first night: Full report as events unfolded. South China Morning Post.

Tam, C. M. (2014, Demember 21). Apple Daily Reference Room. Apple Daily.

The Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau. (n.d.). Constitutional Development. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Touraine, A. (1985). An introduction to the study of social movements.Social research, 749-787.

Tufekci, Z. (2014). Social movements and governments in the digital age: Evaluating a complex landscape. Journal of International Affairs, 68(1), 1-18.

Wong, J. Z. (2014, October 21). Leaderless, the principle of nine: the organizational characteristics of the Umbrella Movement. Pfirereview.

Wu, J. M. (2014). Taiwan and Hong Kong civil disobedience under the factor of China. Cooperation and peace in East Asia.130-144.

Yao, K. H. (2014, September 22). About ten thousands university student engaging in the strike for universal suffrage, a Hong Kong historical day. Apple Daily.

Yu, W. & Cheung, W. M. (2014, October 5). Student was recognized as an auxiliary: for Hong Kong. Mingpao.