Techno-horror and Hauntology: Pulse’s cry for help in a technologically dependent world

The Internet, in all its glittering glory, was first supposed to bring all sorts of people together, with social media connecting everybody to their friends and families and discussion websites such as Reddit, connecting people with similar interests. Yet the polarising properties of these supposedly connecting features manage to “[split] people apart and [make] people feel lonelier than they already are” (Zayd, 2020).

The Internet is a “[t]echnological enigma that feeds off our wants, needs, desires, [and] our pure unrelenting curiosity” (Hollinger, 2020), which is somehow a lot scarier than the techno-horror films about it.

Director Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 2001 techno-horror flick, Pulse, explores these themes of the unknown and the sorrow and loneliness that comes with it on the Internet with its “endlessly cold and desolate atmosphere” (Hollinger, 2020) and its computer ghosts that bemoan the endless melancholy of the black void they call the afterlife: a chilling metaphor for the screens we look at every day of our lives. This article will explore how this film uses techno-horror and its ghosts as a metaphor for our perception of and attitude towards technology, the Internet, and the unknown.

Hauntology

Hauntology finds its beginnings in Algerian-French philosopher, Jacques Derrida’s 1993 work Specters of Marx. In this, he attempts to “rekindle the spirit of the Marxist international” (Riley, 2017) after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Derrida wrote this to show that as much as we can try to bury and hide ideas, such as Marxism, they would always come back, albeit in a spectral manner (Riley, 2017).

Specters of Marx, in a time where “simulacra” and “techno-tele-discursivity” were popular, also appropriately speculated about “the media (or post-media) technologies that capital had installed on its now global territory” (Fisher, 2012). It is acknowledged that Specters of Marx can be interpreted as Derrida suggesting that “tele-technologies” collapse space and time in that “[e]vents that are spatially distant become available to audience instantaneously” (Fisher, 2012). As such, it makes sense that the discourse of Hauntology is connected to a culture where cyber-space had control over the distribution and consumption of everything (Fisher, 2012).

In 2012, cultural theorist and philosopher, Mark Fisher took Derrida’s idea of being haunted by the past and applied it to music and pop culture in his work "What Is Hauntology?".

As much as we can try to bury and hide ideas, such as Marxism, may be tried to be buried and hidden, but they would always come back, albeit in a spectral manner

Fisher uses the term Hauntology to describe a phenomenon in which we, as a contemporary culture, are “haunted” by lost or aborted futures that we were promised because of postmodernity. He applied this concept to music, suggesting that electronic music used to be the music of the future, but that it had “succumbed to its own inertia and retrospection” (Fisher, 2012). The world was not innovative anymore. He suggests that “we were living, in Franco Berardi’s suggestive phrase, after the future” (Fisher, 2012) in music and in other cultures.

Moreover, Fisher (2012) suggests that we always experience the future as haunting because the future is always impinging on the present. Not only does it condition our expectations but it also motivates cultural production.

And what better way to explore and represent Hauntology than films? Derrida, himself, has said that “cinema is the science of ghosts,” making cinema an appropriate medium to portray the uncanny ghosts and the disillusionment for the future of Hauntology (Riley, 2017) because, in a way, cinema is filled with ghosts: ideas once thought gone returned.

Pulse, much like Tarkovsky's Stalker, uses ghosts as metaphors for “traces of a repressed past and of a promised but aborted future” (Riley, 2017).

Fisher (2012) proposes two types of Hauntology; the first refers to something that is no longer there but is still in effect as a virtuality, of which he uses “the traumatic “compulsion to repeat”, a structure that repeats, [and] a fatal pattern” (Fisher, 2012) as examples. The second refers to something that hasn't happened just yet, but is already taking effect in the virtual, which can be “an attractor” or “an anticipation shaping current behavior” (Fisher, 2012). This article will use the first type as a conceptual idea to show how Pulse, a film which may have already faded into obscurity outside of techno-horror fans, informs us of our contemporary attitudes towards technology, our “compulsion to repeat” a “fatal pattern”.

Pulse’s techno-horror today: Haunted machines

Movies have always offered a critical reflection on life and as such, the horror genre, Hollinger (2020) suggests, has always taken inspiration from the trends of their era. Where the post-war period embraced the horrors of nuclear experiments gone wrong (Godzilla) and where the 70s embraced the horrors of serial killers (Texas Chainsaw Massacre), the turn of the millennium finds its horror in the existential terror of the unknown that is the Internet.

As aforementioned, Pulse explores themes of sorrow that come with being surrounded and consumed by technology; it is a film about loneliness and the fear of impending mortality (Hollinger, 2020). Released in 2001, it captures people’s uncertainty as the turn of the millennium introduces the rise of the Internet, the unknown. This new accessibility was overwhelming as people were still trying to understand the Internet and how it’s supposed to bring people together. The timelessness of this film comes from the fact that we’re still trying to figure this out. And not only that, we are still trying to figure ourselves out much like the young protagonists of the film as they try to navigate the strange world of technology where people are reduced to a digital footprint, a stain in this vast world.

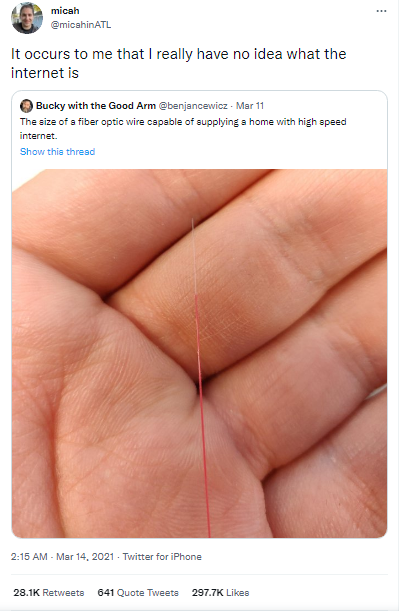

Figure 1: People are still trying to figure out how the Internet works

Pulse portrays this existential horror “by making the absurd seem so believable” (Hollinger, 2020). The arguable absurd ghost epidemic in Pulse happens supposedly because we take our world for granted. Despite the loneliness we feel and the distance we have from reality due to our new machines, who is to say that our attitudes will change to make things better? In the age of technological dependence, we have become unconscious of our existence, zombies that roam this earth unawake. With the main character’s greenhouse being the only source of nature in the film, it presents us a warning that we should connect with the world and our present instead of being lost in the dark abyss of the technological unknown.

Moreover, the ghosts lingering in the characters’ desktop monitors provide a 2001 representation of the ghosts we have in our gadgets in contemporary times: Siri and Alexa. Technology was supposed to make living seamless and convenient, yet as soon as something unexpected happens, “[we] assume that the thing is somehow responsible for the misfortune you are now experiencing” (Krotoski, 2016) due to the fact that we assign so much responsibility and agency to our gadgets. In short, we assume that our gadgets know what they’re doing and when they do something outside of our expectations of what it should be doing, it’s haunted.

Pulse presents us a warning that we should connect with the world and our present instead of being lost in the dark abyss of the technological unknown

Beyond our misunderstanding of how technology works, contributing to our perception of haunted technology, hacking is also something that contributes to this image. Kane from Haunted Machines recalls a friend trolling his wife by changing the settings to their Internet-connected gas heating (Turk, 2015), leading her to believe that their house is haunted.

In line with the slightly horrifying prank, Krotoski wrote a 2016 article detailing her experience with her smart home where her lights started flickering ominously when no one but her and her pets were home. It turns out that her husband, who works as a tester for smart-home products, had been trying out and messing with their house’s lights while he was 35,000 feet up in the air. The mysterious veil of the haunting was lifted and, much like the Wizard of Oz, it was but a man behind the curtain.

Krotoski’s experience perfectly encompasses our behavioural setback of letting unknown and incomprehensible technology in without truly understanding how it works and how its systems could possibly fail their purpose. It is true that these types of technology are so popular because of their ease of access, which users don’t need to think long and hard about. However, it is important to stay vigilant about the things we let in our homes. Revell from "Haunted Machines" warns that “[a]ny sufficiently advanced hacking is indistinguishable from haunting,” and that “[i]f a smart home starts to go wrong, that becomes very sinister and dangerous” due to the fact that people have started to rely on this technology to survive (Krotoski, 2016).

Pulse reflects this ignorance and naivety by using the incomprehensible aspects of this age of technological dependency (Hollinger, 2020). Through this, it explores our somewhat unconscious existence, assisted by our digital caretakers; we have all these things doing chores for us now that we have become detached from daily existence and detached from our understanding of how technology should be assisting us, not living for us.

Part of this ignorance, Revell suggests, is that “it's become acceptable to make things illegible to users” and “to obscure the technical and often financial and legal reality of the system by covering it up with those terms” (Turk, 2015) in regards to companies like Apple leaving their customers in the dark about their software and such by simply saying “It just works”.

Ignorance may be bliss, but is this bliss worth it when your laptop stops working the way you want it to?

The End…?

Perhaps technology isn’t haunted after all. But our present is surely haunted by ideas of the past and society’s compulsion to repeat those ideas. In this case, we find traces of the perception of and attitudes toward technology and the Internet at the turn of the millennium in our contemporary lives: our fear of the technological unknown and our loneliness in front of our screens in a post-pandemic world.

And perhaps we really are living “after the future” as Franco Berardi and Mark Fisher suggest: a world where we are promised Mars colonies and given a technological standstill in mobile phone software development.

Within the dark and desolate world of Pulse, we see reflections of our contemporary life lingering in the corner of the screen, our fear of the unknown, the creepy, and the uncanny. This techno-horror film about loneliness and sorrow in our technologically thriving world perfectly encapsulates the anxiety and uncertainty of our contemporary perception and attitudes towards the Internet, the deep, dark, ever-evolving abyss that we are still trying to understand.

References

Fisher, M. (2012). What Is Hauntology? Film Quarterly, 66(1), 16–24.

Hollinger, R. [Ryan Hollinger]. (2020, November 22). PULSE & FEARDOTCOM: The Rise of ‘Internet Horror’ [Video]. YouTube.

Krotoski, A. (2016, October 27). How smart homes have become the haunted houses of today. BBC Future. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

Kurosawa, K. (Director). (2001). Pulse [Film]. Imagica, Columbia & Daiei Film.

@micahinATL. (2021, March 14). It occurs to me that I really have no idea what the internet is. Twitter. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

Riley, J. A. (2017). Hauntology, Ruins, and the Failure of the Future in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Journal of Film and Video, 69(1), 18–26.

Turk, V. (2015, February 18). Technology Isn’t Magic—It’s Haunted. Vice. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

Zayd, Y. [Yhara zayd]. (2020, October 9). Kairo, Pulse & Fear Lost in Translation [Video]. YouTube.