'Boerenprotest': How Dutch Farmers situate themselves in the Hybrid Media System

'Boerenprotest' is a response of Dutch farmers to the Dutch government. The Dutch government leads the way when it comes to environmental measures to combat climate change. However, Dutch farmers feel like they are paying disproportionately compared to other sectors in the country, like airline companies.

Digital media and technologies have enabled these farmers to disseminate their Message on this political issue into the Dutch public sphere, while also enabling them to contradict the negatively charged Messages of involved politicians which are visible in traditional media. Message is what activists and politicans try to convey to audiences through words, actions, personality characteristics, and so on. It could, then, be asked in what way exactly these Dutch farmers use the affordances of the hybrid media system to make their Message heard.

The Boerenprotest

The Farmers Protest (‘Boerenprotest’) is a series of protests by Dutch farmers taking place since October 1, 2019. Farmers are calling attention to their position in society, the continuously changing regulations, and the general lack of understanding and respect for the daily work of farmers.

The initial protest in October 2019 was organized by two organizations Agractie and Farmers Defence Force (FDF), that have grown considerably in the recent past. Both of these organizations started out as Facebook groups and were established in response to the negative image Dutch citizens have of Dutch farmers. They claim their mission is to make the general publicaware of the fair and safe processes employed by Dutch farmers to produce food, while at the same time having the lowest environmental impact in the world when it comes to agriculture (Agractie, n.d.; Farmers Defence Force, n.d.).

Figure 1 Farmers Defence Force at a 'Boerenprotest'

Arjen Schuiling, spokesperson of Farmers Defence Force, argues that since Dutch farmers are blamed for various environmental issues, they are the first ones to be adversely affected by measures taken at governmental level, such as the decision to halve live stocks of cattle farmers as part of the nitrogen policy and that of buying out farms in the vicinity of nature reserves (Dagblad van het Noorden, 2019).

Dutch farmers argue that they are especially irritated by such measures because not only they are frontrunners when it comes to the production of high quality food – while also having a high emphasis on animal welfare and the environment –, but also because they feel they are more affected by the environmental measures than other sectors in society. Airline companies, for example, also have a huge impact on the nitrogen problem in The Netherlands, but are not as much targeted by governmental measures (R. Debets, personal communication, November 24, 2020).

The Message of Carola Schouten

Before the debate between farmers and the Dutch government emerged in the fall of 2019, one person already stood central regarding the nitrogen problem, namely Carola Schouten. Schouten has been Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality in the Netherlands since October 2017. From the official introduction on the site of the Dutch government it seems like Schouten is committed to helping farmers, horticulturists and fishermen in The Netherlands. Her vision is to create a future for farmers and to improve their economic position (Rijksoverheid, 2018):

“As Minister of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, I want to offer farmers, horticulturists and fishermen a future. I am proud of these hardworking men and women (…). Dutch farmers and fishermen are known for good, affordable and safe food. I want to strengthen the international leading position of the agricultural sector (…) and at the same time improve the economic position of our farmers. They must be given the space to earn a fair living, of course within the applicable nature and environmental standards”.

In this manner, she depicts agriculture – and with that the position of farmers – within The Netherlands as an important aspect of Dutch society. This is her Message. Lempert and Silverstein (2012) argue that the Message that politicians try to convey to the public can be seen as a ‘brand’. Branding is not so much about advertising a tangible product or service, as it is about building a trustable and reliable reputation. When we apply this concept of branding to politics, it becomes clear that the Message of politicians is not so much about the content and position they take on certain issues, but more about the relatable and trustworthy image of the politician (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012).

The Message of Schouten – supporting Dutch farmers – is reinforced by the story of her life . Having been raised on a dairy farm, Schouten and her siblings helped their parents wherever they could. But especially after her father died young, she really got engaged with the farm life (Koolen, 2019). This personal background helps Schouten to make her Message believable and therefore most of her communication acts are on message: they have a sense of realness that appeals to the targeted audience (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012). In this way, Schouten wants to be recognized by farmers as a politican that supports farmers. Indeed, because this will shape her Message further.

“They must be given the space to earn a fair living, of course within the applicable nature and environmental standards”

- Carola Schouten

Nevertheless, some of the measures taken by Carola Schouten are off message, at least seen from the perspective of the Farmer's defence force. One such example is the introduction by Schouten of the so-called silage measure (‘veevoermaatregel’). The intention was that farmers would give their cattle less protein-rich food because this would lead to less nitrogen emissions. It was later recognized that this measure is not only bad for the health of the animals and the production of milk, but also that it was one of the ways to create nitrogen space for the construction of 75,000 homes (NOS, 2020). This measure that Schouten tried to implement is thus against her Message: farmers would be disadvantaged in order to benefit from it elsewhere.

Figure 2 Post of FDF on Instagram

Such actions – and many more alike – are used by supporters of the ‘Boerenprotest’ to counter the Message of Schouten. Lempert and Silverstein (2012) indeed argue that Message is dialogical: politicians produce their Message by giving all sorts of input, but that Message is also co-constructed by other actors in the field. Figure 2 above shows that one of the leading organizations of the ‘Boerenprotest’, Farmers Defence Force, produces images showing how Schouten is not actually helping farmers gain a better future, but is instead ignoring the ideas of Dutch farmers in favor of other initiatives and other sectors (e.g. the plane and the plans for building new offices in the background of the cartoon).

Nevertheless, it is important to note that this cartoon is established by Dutch farmers and therefore merely shows one side of the story. The farmers are portrayed here as nice and friendly, but Dutch citizens may remember the Boerenprotesten as having a militant and aggressive character. Even though spokespersons of Agractie and FDF have stated multiple times that this violent behavior is not representative of the Dutch farmer and their ideals, it cannot be considered as having zero influence on their Message. But this is material for another article.

Choreographing Offline Farmers Protests

Dutch farmers claim that Schouten is reproducing the negative image of farmers by putting forward such ideas as the ‘veevoermaatregel’: it is from these kind of measures that the idea of farmers asthe ones to blame for the environmental problems within The Netherlands comes into being.

This counter messaging of Dutch farmers aimed at the ideas of Carola Schouten is multimodal: they use images, memes, and of course linguistic discourse. Just like there are multiple channels via which Schouten’s Message is communicated, the counter Message of Dutch farmers is also disseminated via various channels. Figure 2 is an example of how (representatives of) farmers are calling attention to continuously changing regulations and the lack of understanding of the farm life via the online channel Instagram. But the construction of Message can also be taken offline, such as when the first ‘Boerenprotest’ took place in the fall of 2019 or when the since then numerous protests by independent parties were organized (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Counter Message of farmers during a 'Boerenprotest'

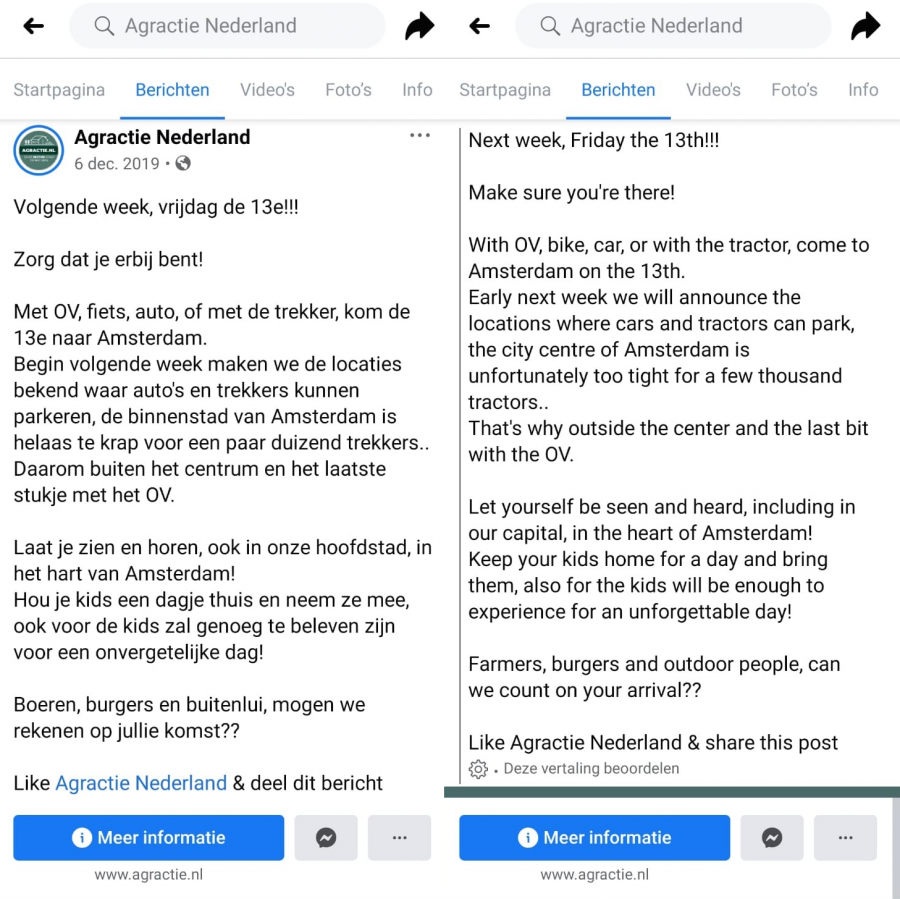

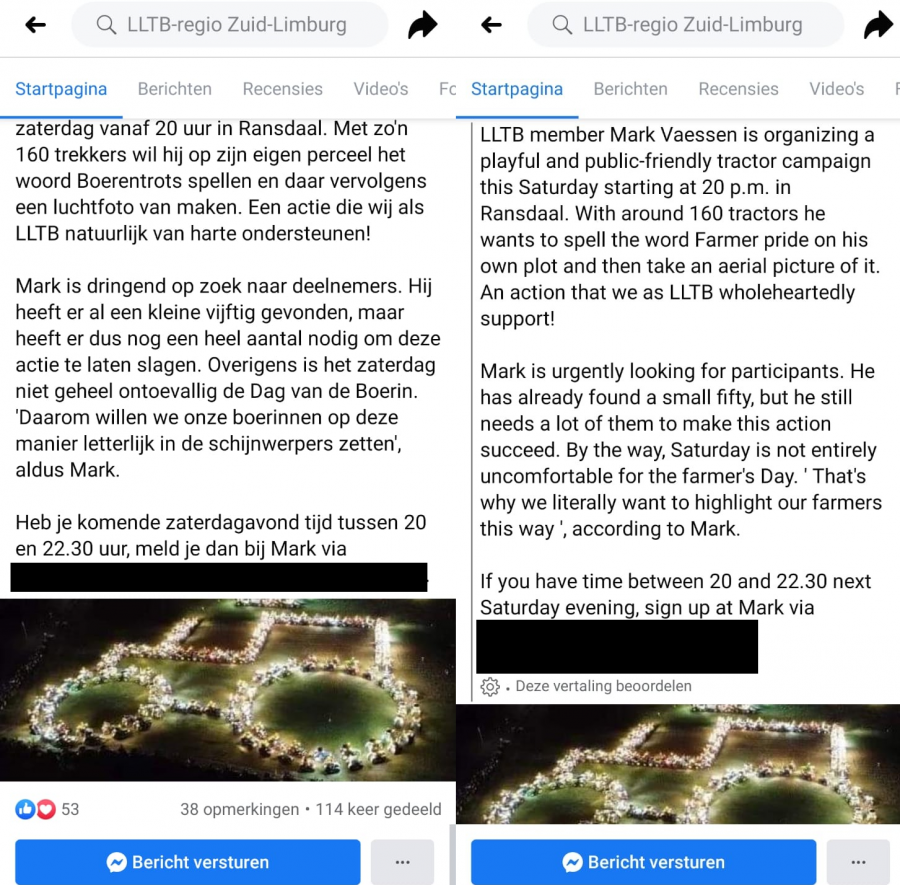

It is oftentimes the case with movements such as the 'Boerenprotest' that the offline protests or assemblies are organized through online channels. Organizations such as Agractie and FDF (see Figure 4), but also individuals (see Figure 5) place a call-to-action on an online platform to gather people who identify with the movement and its Message in reality.

The ‘Boerenprotest’ movement is then the result of what Gerbaudo (2012) calls choreography of assembly. In essence, the choreography of assembly theory explains how activists use digital media to organize offline presence.

The Facebook page of Agractie, for example, is characterized by posts that inform farmers and other people on national and international news regarding the agricultural sector. Examples are news on imported products which are claimed to be local Dutch products by supermarkets or on how Schouten has made it official that she wants to halve the livestock of Dutch farmers. When people are then targeted by call-to-action posts such as the ones in Figure 4 and Figure 5, they may be tempted to engage more in offline actions as they are more familiar with the existing issues.

Figure 4 Choreography of Assembly

Gerbaudo (2012) explains choreography of assembly as “a process of symbolic construction of public space which facilitates and guides the physical assembling of a highly dispersed and individualized constituency”. The Dutch farmers are indeed scattered throughout The Netherlands, but online messages of Agractie, FDF, and independent individuals have brought them together over and over again in offline assemblies. Choreography of assembly, then, is about creating a shared identity online by creating posts like Agractie, in order to organize and mobilize people to pushthem out in the streets and take action.

The Algorithmic Activism of Boerenprotest

The concept of algorithmic activism is also important to consider when talking about Message, because of the attention economy, that isthe fact that human attention is becoming more scarce because of online information and entertainment abundance – . According to Maly (2020) audience labor is a crucial element when it comes to spreading your ideas and your (counter-) Message online. Posting, liking, commenting, and sharing are all important for ranking higher on the popularity principle: the more popular your post, the more visible it will become, and the more people who may take action will engage with your Message .

Figure 5 Algorithmic Activism

Algorithmic activism is then about spreading and interacting with the messages of the politicians or movements you identify with in order to make them more visible. Dutch farmers are indeed performing audience labor by liking and sharing the messages and posts of, for example, Agractie and Farmers Defence Force.

An example of this is the number of people who have liked the Facebook page of Agractie, namely 28.528 people. Maly (2019) argues that algorithmic activism is not only about the fact that the people who perform audience labor agree with the message they interact with, but also that they understand the digital affordances of the online platform on which they are interacting. From Figure 5 above, for example, it becomes clear that people adhering to the ideas of the ‘Boerenprotest’ know that sharing the Facebook post will eventually engage more people to take offline action than liking or commenting on it will: the number of shares is much higher than the amount of likes and comments.

From this it becomes clear that algorithmic activism is a very important concept for movements such as the ‘Boerenprotest’ in order to perform choreography of assembly. When Dutch farmers comment more on posts like the one shown in Figure 2 or when they share posts such as the ones shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, more people, who were not aware until then about the Message of Dutch farmers or the counter Message they produce against Schouten, will become familiar with the problems farmers are facing. When these people in turn start to identify with the Message of Dutch farmers, they may be encouraged to take offline action as well.

Boerenprotest in the Hybrid Media System

Through counter messaging and the organization of offline events through digital media, Dutch farmers may situate themselves in what Chadwick, Dennis and Smith (2016) call the ‘hybrid media system’. Since the rise of digital technologies, we have seen a chaotic transition period from traditional media to digital media. This transition is chaotic because digital media is facilitating all kinds of actors besides journalists to contribute to the news, while old media is still there and keeps having a great influence on the production and distribution of news.

“Dutch farmers are creating their own Message that suits their own goals (…), while at the same time modifying the agency of Schouten”

In the traditional news system, politicians like Carola Schouten had the power to distribute their Message without interference from other actors; journalists were the gatekeepers between politicians and the public. Now in the hybrid media system, other actors like the followers of the ‘Boerenprotest’ movement, citizens, and social media users have access to technologies that enable them to spread their Message or counter Message. Chadwick, Dennis and Smith (2016) indeed argue that within the hybrid media system, “different actors create, tap, or steer information flows in ways that suit their goals and in ways that modify, enable, or disable the agency of others, across and between a range of older and newer media settings.”

Dutch farmers are situating themselves within this hybrid media system and steering information flows in ways that suit their goals by using of counter messaging and choreography of assembly. Schouten depicts herself as fighting for the future and better economic circumstances for farmers, while she is introducing ideas and initiatives that go against the interests of farmers (e.g. the silage measure or the livestock halving).

Message in a Hybrid Media System

Schouten is thus trying to keep up her Message of working in the best interest of farmers, but farmers are countering this Message by producing negative messages about Schouten on social media or by going out on the streets and calling attention to their perspective on these matters (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012). In order to engage as many people as possible with these offline protests, Agractie, Farmers Defence Force, and multiple independent actors make use of choreography of assembly. They are creating a shared identity online through creating posts. By creating this shared identity, Dutch farmers from all over The Netherlands are organized and mobilized to come together in offline assemblies (Gerbaudo, 2012). These protests again reinforce the counter Message of the Dutch farmers targeted at the Message of Carola Schouten.

In short, it is by using counter messaging and choreography of assembly that Dutch farmers are creating their own Message – their own information flow – that suits their own goal of calling attention to changing regulations and the position of farmers in Dutch society, while at the same time modifying the agency and consequently the Message of Schouten. Counter messaging and choreography of assembly, thus, enable the Dutch farmers to situate themselves in the hybrid media system and cause a fracture in the Message of Schouten and reconstruct her Message in such a way that it suits their interests (Chadwick, Dennis & Smith, 2016).

References

Agractie. (n.d.). Missie & Visie. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://agractie.nl/

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., & Smith, A.P. (2016). Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems, and Media Logics. In Bruns, A., Enli, G., Skogerbø, E., Larsson, A.O., & Christensen, C. (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Introduction. In Gerbaudo, P. (Ed.), Tweets and the Streets. Social Media and Contemporary Activism (pp. 1-17). London, United Kingdom: Pluto Press.

Koolen, K. (2019, October 31). ‘Ik word een harde zakenvrouw, dacht ik’. In ea.

Lempert, M., & Silverstein, M. (2012). Introduction “Message” Is the Medium. In Lempert, M., & Silverstein, M (Eds.), Creatures of Politics (pp. 1-57). Bloomington, United States: Indiana University Press.

Maly, I. (2019, November 26). Algorithmic populism and algorithmic activism. In DiggitMagazine.

NOS. (2020, August 19). Veevoermaatregel gaat van tafel, levert te weinig stikstofreductie op.