Calling out the homofobus

The anti-abortion van, depicting photos of aborted foetuses, has been present on streets of Polish cities for a long time: it can be spotted on squares or driving through city centres. It is hard to say exactly when it started, but the pro-life organisation behind this social action, “Fundacja Pro-Prawo do Życia” (“Pro-Right-to-Live Organisation") published a statement on their website in 2017: “We will not stop the action as long as unborn children are murdered in Polish hospitals.” Recently, however, they've unveiled a new protest: the homofobus.

The situation became more complicated when the Pro-life organisation decided to focus not only on abortion but also extend their action to an anti-paedophilia van. The idea itself is understandable, since paedophilia is illegal and remains a problem in modern society. The problem is that the Pro-life organisation blames paedophilia solely on the LGBT+ community. This time they put homophobic slogans on their van, which has been met with some disapproval.

In this article I will analyse the role of social media in this ongoing action, as well as the response of people on social media.

homofobus: the homophobic truck

The van owned by the Pro-life organisation has some controversial slogans put on it.

"The LGBT lobby wants to teach children: Four-year-olds: masturbation; Six-year-olds: consenting to sex; Nine-Year-Olds: The first sexual experiences and orgasms; *based on The Standards of Sex Education in Europe"

On the left side of this banner there is also a crossed-out LGBT flag, together with words "stop paedophilia", which is supposed to suggest a connection between this illegal act and homosexual people.

"Pederasts live an average of 20 years shorter; Paedophilic acts are 20 times more common among homosexuals"

On the right side there is a picture of two naked men, holding the LGBT+ flag and the text: "People like these want to educate your children. Stop them."

The law

People who believe the Homofobus to be harmful are trying to stop the organisation behind it. In fact, it has been sued many times by institutions such as the Association for LGBT People Tolerado, the Polish Ombudsman, and bodies of the Council of Europe. However, Polish law does not recognise its presence on the streets as an act of intolerance. The provisions for the prosecution of hate speech apply only to people who are discriminated against on the basis of their faith, sex and nationality, but not sexual orientation. Discrimination against LGBT+ people is a big problem in Poland: Andrzej Duda, the re-elected president recently stated that the LGBT movement is more destructive than communism.

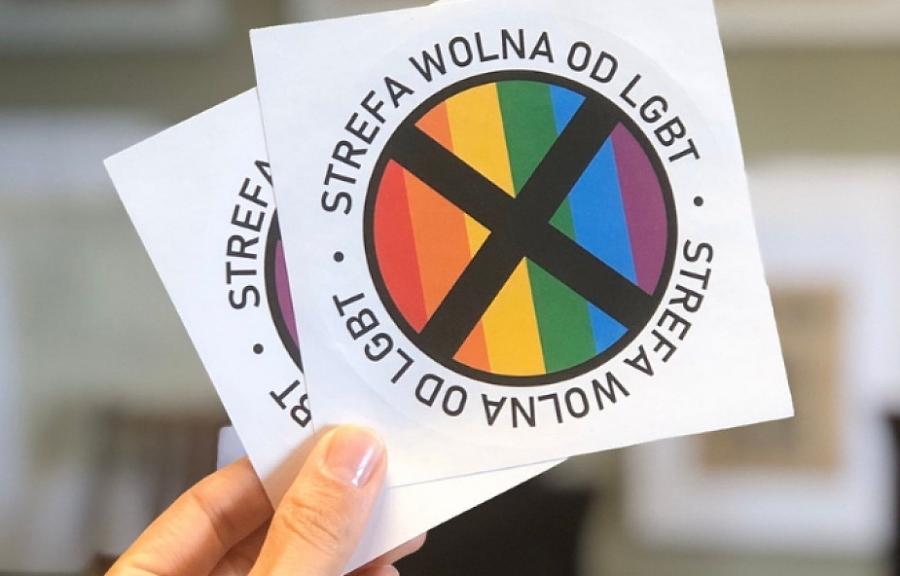

In February 2019, the Mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, signed a declaration supporting LGBT+ rights and announced that he intends to follow World Health Organization guidelines in including LGBT+ topics in school sex education programs in Warsaw. The declaration was met with disapproval from the ruling party, who retaliated by creating so-called "LGBT-free zones": areas where local government resolutions have declared them free of "LGBT ideology". These resolutions have no legal effects and are considered primarily symbolic, but they gave homophobia an official status and local councilors interpret it as a legal basis for homophobic discrimination.

"LGBT-free zone" sticker, distributed by the newspaper "Gazeta Polska", promoting the idea of "LGBT-free" zones in Poland.

Reactions online: citizen witnessing and digital vigilantism

Even though the Polish law allows the Homofobus on the streets, people are still trying to stop it, or at least express their disapproval. Easy access to the internet enables everyone to not only to share their opinion but also document events and post them online immediately. Nowadays most of us have a smartphone, so we are able to record and immediately share events we witness. "Social media platforms and mobile devices in particular amount to a mutual augmentation of formerly distinct surveillance and information sharing practices" (Trottier, 2012).

People who find the Homofobus inapproproate have started calling it out on Twitter:

Translation: "not gonna lie - I would happily destroy the homofobus right now"

Translation: "I must admit, I'd like to destroy the homofobus."

By sharing statements like this, people are trying to articulate their values and disapproval for actions like the Homofobus. Twitter is full of statements similar to the one above, since as a social media app it allows everyone to express their opinions and thoughts. By doing so, they can also encourage others to agree with them.

Showing off how one has taken the law into their own hands and tried to stop the van is also popular.

Translation: "Today at the crossing, the Homofobus was shown some "fuck you" by me and dozens of other pedestrians. What is more, I was standing at the traffic lights to go to Defilady Square and some genius driver decided to drown out anti-human slogans by honking the horn, for which he received a thunderous applause. Thanks man!!!"

By posting this tweet, the author is not only letting others know that he condemns the Homofobus, but also encouraging others to do the same.

Being a witness allows one to not only share information about the event, but also express an opinion about it online, especially when legal authorities are involved.

"The dudes from @Policja_KSP (Warsaw Police Headquarters) have almost shit their pants, from the exhaustion caused by executing instructions from the head-office."

The author of this tweet has called out the behaviour of the police officer. In the video attatched to the tweet the cycler is blocking the Homofobus by stopping his bike in front of it. The police officer pushes the cycler to help the van move forward. Other people might see this as the officer simply performing his duties, but the author of the tweet has framed it as wrong-doing.

The police are not the only object of callouts connected to the Homofobus case:

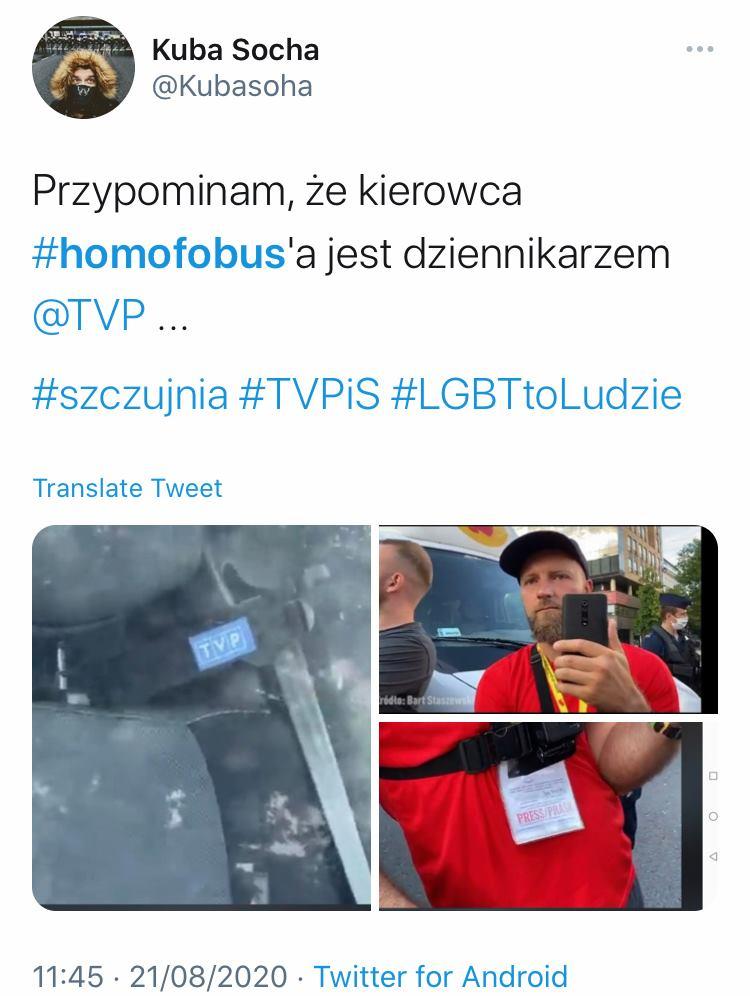

"Let me remind you that the homofobus' driver is a TVP journalist"

Twitter users have exposed the Homofobus' driver as a journalist for TVP, the Polish public television station. TVP itself has never admitted to its connection with the “Fundacja Pro-Prawo do Życia” organisation, however their extreme-right and homophobic beliefs are broadly known in Poland. TVP is supported by the far-right-wing ruling party PiS. On March 6th, 2020, President Andrzej Duda signed an act awarding PLN 2 billion to the state media, with 87,7% going to TVP.

This tweet was supposed to reveal the connection between the Homofobus and the national televsion station. The author did not censor the driver's face, making it easier to identify him.

Under the hashtag #homofobus, people have also started sharing up-to-the-minute information about the van's location. Posting the location may seem quite innocent, since the target is a vehicle and can easily drive away. Some Twitter users find this kind of information useful: they can avoid the Homofobus or, on the other hand, try to confront it.

On June 27th, 2020, a transgender activist known as Margot attacked a pro-life driver and tried to destroy the truck. She was arrested and sentenced to two months detention. Many who had earlier expressed indignation at the actions of the police also criticized Margot, denouncing the use of force and vulgarity.

Other people expressed that it is better to avoid breaking the law and try to perform a civil action instead.

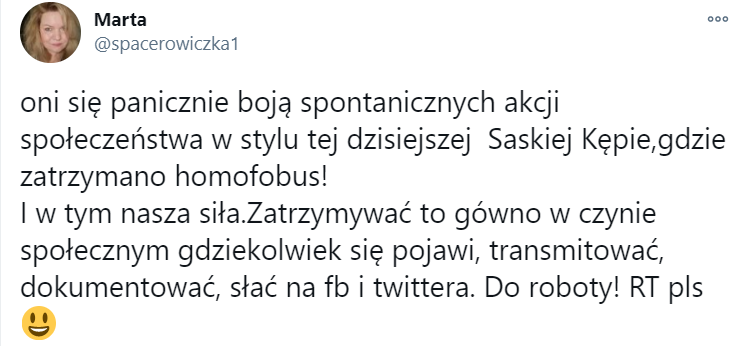

"They are terrified of social actions like today's one at Saska Kępa, where the homophobus was stopped! This is our strength. Let's stop that shit by citizen's arrest wherever it goes, broadcast it, document it, post it on FB and Twitter. Let's go!"

Even though people are well aware that the Homofobus is able to avoid legal prosecution, they still promote citizen's arrest as an opportunity to stop it, at least temporarily. This way they can also make it difficult for the Pro-life organisation behind the van to continue their actions.

The call to "(...) broadcast it, document it, post it on FB and Twitter." also shows that citizens know digital media affordances enable them to promote this kind of behaviour. The case of the Homofobus went viral and got even more publicity thanks to YouTube and Instagram.

An influencer's response: #stopthetrucks

Polish vlogger Krzysztof Gonciarz, who has over 1 million subscribers on YouTube, decided to take matters into his own hands. Together with the Noizz portal they organised "Stop Ciężarówkom" or "Stop the Trucks." They created their own truck and drove it around the streets of Warsaw. The main goal of this campaign was to belittle the Homofobus and show how ridiculous it is for the law to allows it spread propaganda.

"Anyone can put a banner to a truck and talk rubbish; I can't believe that's legal". Krzysztof Gonciarz with his truck.

Gonciarz decided to peacefully bring attention to the Homofobus problem. He stated: "We wanted to do something that would amuse people and highlight the problem of anti-LGBT vans. But also something that won't add fuel to the fire. Our action is a comedy performance."

"What do trucks want to teach children? Four-year-olds: spitting lunch; Six-year-olds: swearing; Nine-Year-Olds: rolling around on the store floor"

The influencer's truck is a parody of the Homofobus. The slogans on it are very similar, but instead of attacking "the LGBT lobby", they attack "the truck lobby." Instead of a crossed-out rainbow flag, there is a picture of a crossed-out van with the text "Stop ciężarówkom" - "Stop the trucks."

In Warsaw Gonciarz and journalists from the Noizz portal drove through the city, preaching their "anti-truck" slogans through a megaphone. The video from this event is available on Gonciarz's Youtube channel, and the live story is saved on the Noizz Instagram profile.

Gonciarz says that he noticed a growing tension between the two sides, so he decided to "do something that would pop the balloon of fear." The whole event was broadcast live on Instagram not only by the creators, but also by random pedestrians who spotted the influencer's truck. People helped Gonciarz finding the Homofobus' location by tagging him on social media whenever they spotted the anti-LGBT van. This crowdsourcing practice is possible thanks to geolocation functions of social media: people can easily send their GPS location to others. This illustrates the online-offline nexus feature of digital vigilantism: being in a physical location and then posting it online helped the case.

It worked: the two trucks met. As the influencer stated, they did not escalate the conflict but instead drove right behind the Homofobus, trying to drown out their anti-LGBT slogans with anti-truck slogans, until the Pro-life organisation's van hid in a parking lot.

The role of social media

Kaplan and Haenlein (2011) have referred to social media as a "group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of the Web 2.0 and that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content." Easy access to Twitter, Instagram and YouTube enables us to read other people's opinions and share our own. We can also support each other simply by reacting to posts, sharing them, or leaving a comment. A few touches on a smartphone screen can help someone's post go viral.

"Digital vigilantism is a process where citizens are collectively offended by other citizen activity, and coordinate retaliation on mobile devices and social platforms" (Trottier, 2017). In case of the Homofobus, the law was unhelpful, which made people want to post their opinions online even more. Constantly sharing the van's location is a good example of how everyone can contribute to a case. All you have to do is be in the right place and time, spot the van and share its location on your social media profile. If you do not want to physically stop the truck yourself, there is a possibility that others will do it after seeing your message.

All of this is possible due to the affordances of social media. The more people mention, like, comment and share, the more attention a case gets and the greater likelihood that others will get involved. It is even better if you decide to make your opinion more salient and frame the case by defining the problem or stating your moral judgement.

Conclusion

Feeling helpless in the face of the law has led many people to feel obligated to post about the Homofobus online. Some just want the matter to be publicized, discussed, and shamed. If a bigger part of society recognises the Homofobus as a problem, maybe the authorities will consider it an act of intolerance and adjust the law. But some people share information about the van's location to provoke a physical response in the offline world. When the information is on the Internet, everyone can see it: the person who wants to protest online, the person who wants to express their dissatisfaction by showing the middle finger to the driver, or the person who is so outraged that they will physically hurt the driver, becoming a vigilante.

Violent reactions and reveal the identities of people involved with the Homofobus are some of the negative aspects of the digital vigilantism. On the other hand, many people feel that online reactions and sharing information is the only way they can bring justice, since the police and law are not going to help.

The peaceful and satiric performance from Krzysztof Gonciarz and the Noizz portal is also an interesting outcome. While the event itself happened in the offline world, it was also fully reported on online. Thanks to their counter-protest, many more people found out about the Homofobus problem, and those who had known about it before felt encouraged to share their thoughts and the Homofbus' location online, making them digital vigilantes themselves. It shows how powerful social media actually are - by creating a space for people to share their voice, they also gave them a "weapon" to fight injustice.

Despite the vigilantes' best efforts - both digital and traditional - the Homofobus continues its journey through Poland. Does it mean that the civilians' efforts were pointless? Or is it just the beginning of a bigger conflict? Whatever happens, those who despise the Homofobus can at least get some emotional support on Twitter.

References

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2011). Two hearts in three-quarter time: How to waltz the social media/viral marketing dance. Business horizons, 54(3), 253-263.

Trottier, D. (2017). Digital vigilantism as weaponisation of visibility. Philosophy & Technology, 30(1), 55-72.

Trottier, D. (2016). Social media as surveillance: Rethinking visibility in a converging world. Routledge.