How propaganda works in the hybrid media system

They catch our attention, waste time, and bombard us with clickbaity titles whenever we scroll social media: junk news and fake news are significant problems of today's internet. Not only do they annoy us, but they also convey a foreign agenda.

In this article, I will show how fake and junk news can be utilized as a tool for spreading disinformation and propaganda in the hybrid media system.

"Independent Political Journal"

Niezależny Dziennik Polityczny (NDP) - "Independent Political Journal" is a news website, providing its readers with political articles written in Polish since 2014. At first glance, the website looks like many other news portals: at the top of the page, there is a logo, hyperlinks that take you to categories such as "society", "Poland" or "world", and links to several social media pages. Most of the home page is devoted to thumbnails and titles of the articles featured there. The only thing that may seem surprising at first is a lack of advertisements, which normally are very visible on news portals since news portals put ads up for monetary purposes.

Even more alarming is the fact, that all of the articles' subject matter seems to revolve around slander of the Polish government and army. They also have clickbait titles, for example, "HORRIBLE news for Kaczyński (Polish deputy prime minister). It came to light on Monday morning", "The Northern Gas Pipeline, i.e. a monument to Polish stupidity", or "Military equipment instead of medicines - Poles will pay for it with their lives". By using such highly emotionally charged titles, the authors try to attract the attention of the reader who, intrigued, clicks on the link and reads the article. Since there are no advertisments placed on the portal, the authors may be getting paid by a sponsor or doing it voluntarily. The question is - what is their goal?

By using such highly emotionally charged titles, the authors try to attract the attention of the reader who, intrigued, clicks on the link and reads the article

Reading the "about us" page provides the reader with the information that NDP is a private portal "independent of offices, State, and government organizations". The entire message, however, is written clumsily and has several grammatical mistakes in the Polish language, which suggests that it has probably not been written by a native speaker.

In fact, NDP has been exposed by the OKO.press portal as a website linked with the Russian services that spread disinformation consistent with Russian narratives.

Fake news and junk news

The idea of “fake news” is not a new one – misinformation has been spread long before the times of Web 2.0. This term has gained even more publicity when during a press conference in 2017, Donald Trump refused to take questions from CNN reporters, calling them “fake news” (Higdon, 2020). In fact, during the first year of his presidency, Trump has used this phrase over 400 times. However, many pieces of information that were claimed by him to be "fake news", were in fact only items disagreeing with his views. As Ethan Zuckerman stated in his article, for Trump "fake news" are "real issues that don't deserve as much attention as they're receiving."

Venturini (2019) noticed, that "the term 'fake news' has become a weapon to discredit opposing sources of information". He elaborated that using this phrase is misleading since it suggests that "malicious pieces of news are manufactured, while reliable ones correspond directly to reality". Moreover, whether the information is true or not is not as relevant as how spreadable it is. This is of particular importance in the economy of virality, in which rapid circulation of content from one user to another is crucial since it enables the commercialization of information and goods. The more people "react" to the content - by commenting it, sharing it, or leaving a "like" - the more money the author can get from advertisements posted on the website. Apart from that, the information about the users visiting the website can be collected, compared, and sold as well. It means that what actually matters is not the content itself, but the attention of the audience.

To gain more crowd and "clicks", the news authors are likely to use clickbait titles, eye-catching phrases, and other methods designed to catch the attention of people scrolling through news or their social media pages. Since people are consuming this kind of content addictively, as they consume junk food, Venturini proposed the term "junk news". This term defines information that is designed to be viral, but at the same time is irrelevant (Venturini, 2019). It is still dangerous because it redirects the attention of the community and "saturates public debate, leaving little space to other discussions, reducing the richness of public debate and preventing more important stories from being heard" (Venturini, 2019).

Construction of news is affected by the hybrid media system, which was defined by Chadwick as a "system (...) built upon interactions among older and newer media logics—where logics are defined as bundles of technologies, genres, norms, behaviors, and organizational forms—in the reflexively connected social fields of media and politics." (Chadwick, 2017). He elaborated that the line between the roles and norms of news production known from old and newer media is blurred: now news can be produced by both a professional news company, as well as by an amateur blogger.

Thanks to the Internet society has gained a new public space for political discourse. People can look for information, discuss and share their opinions on various social media pages, news portals, blogs, and other pages. However, "cheap, fast, and convenient access to more information does not necessarily render all citizens more informed, or more willing to participate in political discussion" (Papacharissi, 2002). The presence of junk news and fake news that supports misinformation and propaganda has a significant influence on the information that the audience receives.

The editor-in-chef

The person behind NDP is Adam Kamiński - a Warsaw University graduate in his forties.

Adam Kamiński's Facebook profile with Polish flag and a statue of an eagle in the background picture

The background picture with a Polish flag on his Facebook profile suggests that he is a patriot. On his social media, apart from memes, he mainly publishes articles from the NDP. Apart from a few laconic messages and a series of posts shared by him, there is no information on the Internet about Adam Kamiński, a law graduate of the University of Warsaw and an editor. Asked by the OKO.press reporters for an interview on his news portal, he claimed to be busy and abroad. On the proposal to conduct an interview via the Internet, he replied: "I am sorry. I haven't used Skype recently, because I have received threats from the Ministry of National Defense several times."

His profile picture has been stolen and the persona of the Polish editor-in-chief is completely made up

People from his Facebook friends list, asked about him by reporters, unanimously say that they have never seen him in person and do not remember how they became "friends" on the platform. This would be surprising if not for the fact that Adam Kamiński does not exist. His profile picture has been stolen from a Lithuanian orthopaedist – Andrius Žukauskas - and the persona of the Polish editor-in-chief is completely made up.

Andrius Žukauskas - a Lithuanian orthopaedist from whom the Kamiński's profile picture was stolen

In this case: who is really behind the portal and what is their goal? As reported by The Baltic Center for Investigative Journalism Re:Baltica: "Polish national security institutions off record claim that Dziennik is led by Russia’s secret services, but publicly have not offered proof of the accusation."

Russian disinformation in Poland

As stated by Robert Gorwa in his research, "Russia is rumoured to be actively funding nationalist groups, spreading propaganda online, and using other indirect means to destabilize the Polish state" (Gorwa, 2017). Even though it is not always easy to confirm unequivocally "Russian troll" comments, there are a few hints leading to this conclusion. For example, mistakes in Polish grammar, a lack of characters such as "ó", "ł", "ż", which are typical for the Polish alphabet, as well as using argumentation known from Russian pro-Kremlin articles (Wierzejski, 2016).

Polish analytics state that the first wave of disinformation has started after the Maidan protests in Kiyv in 2013. It began flooding the Polish internet with anti-Ukrainian statements, using the complex history of the two nations as a tool to instigate quarrels with each other. The influence of Russian misinformation continues, extending the subject matter to Polish politics and the army. Paradoxically, they also try promoting extreme Polish nationalism and anti-Russian views in order to make Poland seem unreliable and "hysterical" in the eyes of Western Europe (Lucas, Pomeranzev, 2016).

Using social media affordances makes it easier than ever for state actors to spread propaganda on a massive scale (Prier, 2017). No great skills are needed to set up a website that will look like a legitimate news portal, and getting fake social media profiles is even easier. Those who wish to spread disinformation can do so at a relatively low cost on a large scale. "The combination of fake accounts, fake news sources, and targeted narratives propagated via social media is increasingly becoming portrayed as a new form of digital propaganda" (Gorwa, 2017).

It is particularly visible in the hybrid media system, where participants can affect "information flows in ways that suit their goals and in ways that modify, enable, or disable others’ agency, across and between a range of older and newer media settings" (Chadwick, 2015). A powerful person with resources, or representatives of governments who have means can easily hire professionals who will spread the preferred narrative on the Internet. After all - "those who have the resources and expertise to intervene in the hybrid flows of political information are more able to be powerful" (Chadwick, 2015).

Fake news: letter from the generals

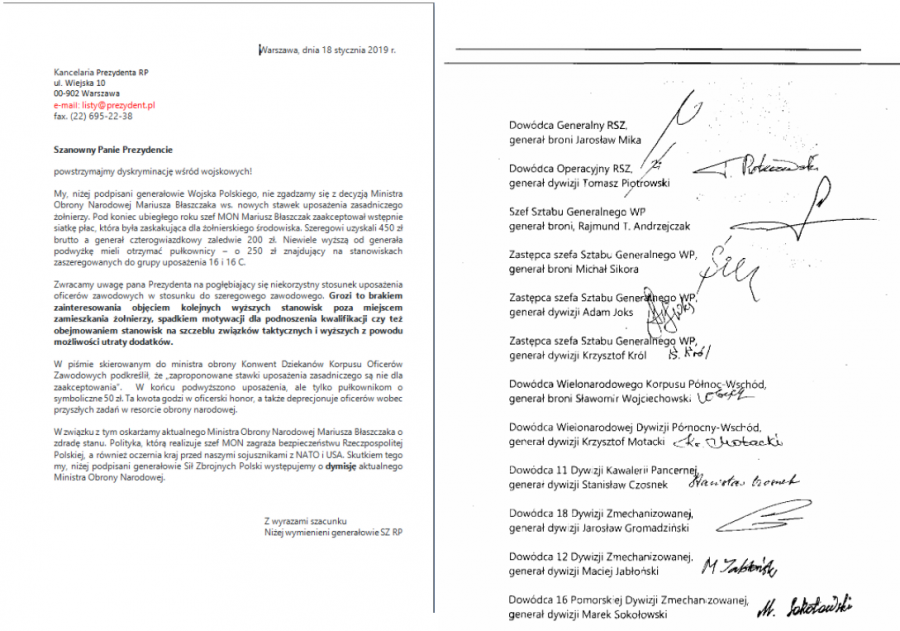

The title of the article: "Scandal! The generals demand the resignation of Błaszczak! An open letter to the President". The picture depicts Polish minister being targetted.

On January 18th 2019, NDP published an article with the title written in a sensational tone: "Scandal! The generals demand the resignation of Błaszczak! An open letter to the President". The said letter has false signatures of Polish generals, in which they allegedly demand the resignation of the minister of defense and accuse him of high treason.

The article starts with the following statement: "An open letter to the President of the Republic of Poland has been sent to our editorial office as well as to the editorial offices of many Polish press portals. The editorial staff of the "Independent Political Journal" website made an attempt to contact the Ministry of National Defense for a comment on the issue of the "open letter", but received no reply."

However, The Ministry of National Defense claimed in a comment provided for the Demagog portal that the article is based on fabricated information. The ministry quickly issued a disclaimer to the media in this regard, stating also that they have not received any message from the NDP about the issue, as well as that this portal is known to distribute fake news.

A letter allegedly sent to the president with fake signatures of the generals on a separate screenshot

The fake nature of the letter allegedly sent to the NDP is indicated primarily by the fact that it was presented on two separate graphics: one with the content of the letter itself - as a screenshot from a text editor, and the other - a separate page with forged signatures of Polish generals.

Demagog portal, which debunks fake news and misinformation, commented that the article posted by NDP is another example of disinformation against the Polish Armed Forces: "in the light of numerous other false information on the sphere of national security of Poland appearing on this portal, it makes it necessary to assume that its authors are fully aware of the disinformation nature of their activities."

The aim of the article published by NDP was to spread misinformation among people and make them believe that there is a disagreement between the people in charge of the Polish army and the authorities of the country. It was supposed to convey to the people that the army and government are incompetent and at odds. In order to do so, the authors not only posted the fake news on their website but also used the possibilities of the hybrid media system and they secretly promoted their propaganda on Facebook.

The audience's response

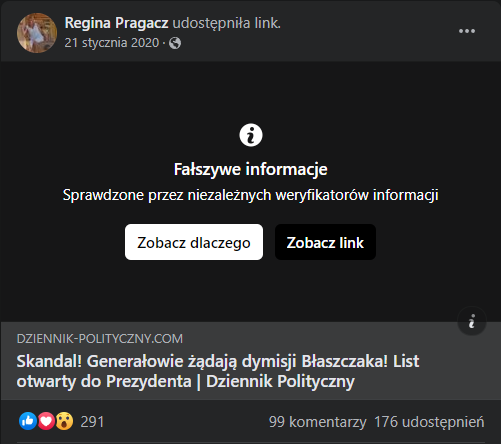

A few people have shared NDP's abovementioned article on many different anti-government Facebook groups. However, after a closer examination of their profiles, they seem to be fake: the people behind them only share various political news on their walls and do not provide any other content or information.

NDP's article shared by a fake account on one of political Facebook groups

It is important to highlight the fact that Facebook flagged the shared article as "Fake news checked by independent information verifiers." Although the moderation on social media may seem controversial, it is a necessary process: "Platforms must, in some form or another, moderate: both to protect one user from another, or one group from its antagonists, and to remove the offensive, vile, or illegal—as well as to present their best face to new users, to their advertisers and partners, and to the public at large" (Gillespie, 2018).

The reader can also click the "see why" hyperlink to read who confirmed the article as fake, and open the article with the other hyperlink. It shows that Facebook is trying to fight against the misinformation being spread online. Audience labour has a significant value in the hybrid media system, because it lets the content gain more visibility and therefore enables it to reach more audiences. The article got re-shared 176 times and received almost 300 reactions and 100 comments.

It shows that people behind the article are aware that for their content to really be seen they need to share it on political groups on Facebook, where it can resonate among legitimate articles shared by others. Through such a procedure, the casual user will read the article - that may even fit their views - and believe the content without verifying the information provided to them. Even if the authorities, independent verifiers, or the platform debunks the information later, it may not reach the audience already convinced that the fake news was telling the truth.

The more engagement a piece of content gets, the more likely it is to be rewarded by the algorithm

The engagement of the audience - likes, comments, and shares - contributes to the spread of information on the Internet: "the more engagement a piece of content gets, the more likely it is to be rewarded by the algorithm". The content shared, or reacted to by many users will likely go viral. In the case of an innocent meme, or a picture of a funny cat, the outcome is harmless. However, the situation is different when it comes to sharing news: "By re-posting contents that they hope will interest their followers, users (...) contribute to the maintenance of interpersonal communication networks propitious for junk information" (Venturini, 2019).

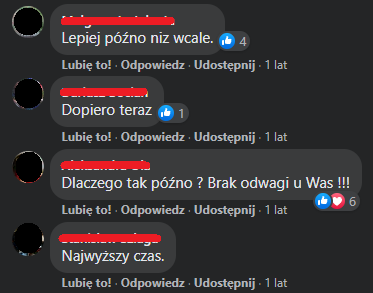

Comments under the NDP's article shared on one of the political groups: "Better late than never"; "Only now"; "Why so late? Your lack of bravery!!!"; "It's about time"

The comments under the article on NDP's website as well as those on Facebook groups indicate that the goal of the people spreading misinformation has been achieved: many people not only believed the fake article they had read, but also engaged with it and expressed their support towards generals allegedly demanding the resignation of the minister.

Junk news: NDP's main content

Although the news about the fabricated letter was an original article of the NDP, a closer look into their website suggests that most of the content shared here is in fact junk news stolen from other news portals.

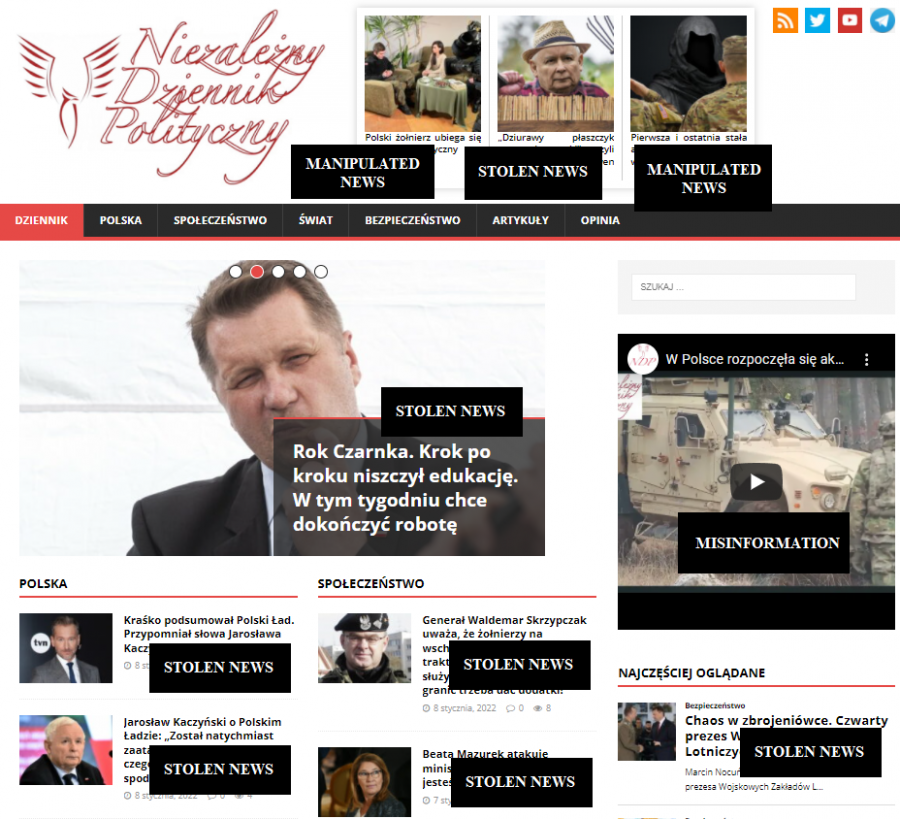

Screenshot od NDP's main page with stolen, manipulated news and misinformation marked

In order to make their website seem more legitimate, people operating it adopted the following strategy: they are copying news from other portals and sharing them as their own, sometimes adding an additional sentence or two to change the narrative.

For example, this article about the immigrant crisis on the border with Belarus was stolen from portal salon24.

NDP's article's (on the left) content stolen from salon24's article (on the right).

The article about the critique of one of the Polish euro-deputies on the minister of education was stolen from Onet.

NPD's article's (on the left) content stolen from Onet's article (on the right)/

In fact, most of the content shared on NDP is stolen news, put there as decoy to make the website look professional. It is especially visible in their statistics: the junk news posted every day gets a low number of views, from zero up to a hundred, and the fake news they create themselves and then promote on Facebook gets tens of thousands of views.

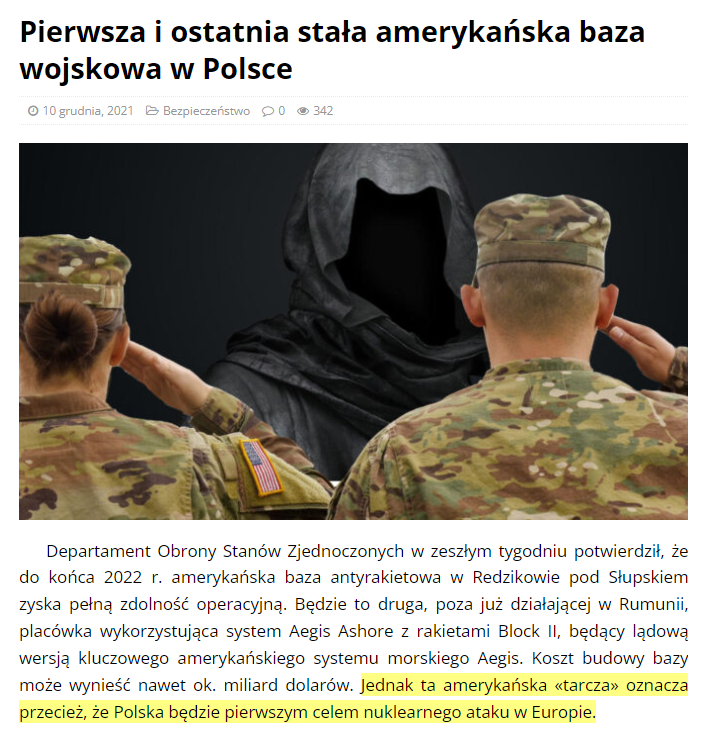

However, people behind NDP also seem to realize that users accessing their site through the links shared on Facebook may read other articles - junk news - on their site. Therefore, they not only steal material criticizing the Polish government and military from other portals but also add a few extra sentences to make sure that the meaning of the message matches the narrative they are trying to convey. The article about the American anti-missile base that is being built in Poland was stolen from portal WNP, however, people from NDP decided to add one more sentence at the end of the first paragraph.

The highlighted sentence, that was added to the stolen article by NDP: "However, this American "shield" means that Poland will be the first target of a nuclear attack in Europe."

The extra sentence is supposed to make the reader feel anxious about the American anti-missile base. It does not have to make people scared of the cooperation between USA and Poland, but it will sow the seeds of uncertainty among people, who will remember about it next time they come across other news about this matter.

It is also worth noting, that NDP uses media frames in order to make their audience think exactly how they intend them to think by posting the article. The original news about the American anti-missile base came with a photo of the base, but the stolen version shared on NDP has a different picture of two soldiers saluting the Grim Reaper in the back. The juxtaposition of such an emotionally loaded photo with the article suggests that the presence of an American base in Poland is something ominous.

Everyone can produce information in the hybrid media system

The actions of the Independent Political Journal are based on spreading false information and harmful fake news on social media. The fake news and junk news they are publishing are meant to evoke fear fueling the internal conflicts of Poland. Incitement of the public debate, the radicalization of Polish citizens, and ridiculing the country's government are weapons of Russian propaganda.

Thanks to the affordances of social media platforms, as well as the hybrid media system, any kind of information can be spread among large audiences. We need to remember that these resources are available not only for people with good intentions but also for those with their own agendas. They use half-truths, fake news, junk news, disinformation, and conspiracy theories not with the goal of making someone believe them, but to make everything else less credible.

References

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., Smith, A. (2016). Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems, and Media Logics. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A.O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Routledge, pp. 7-22.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. Yale University Press.

Gorwa, R. (2017). Computational Propaganda in Poland: False Amplifiers and the Digital Public Sphere. In S. Woolley, N. Howard (Eds.), Working Paper 2017.2. Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda.

Higdon, N. (2020). The Anatomy of Fake News: A Critical News Literacy Education (First ed.). University of California Press.

Lucas E., Pomeranzev P. (2016). Winning the Information War Techniques and Counter-strategies to Russian Propaganda in Central and Eastern Europe: A Report by CEPA’s Information Warfare Project in Partnership with the Legatum Institute; Center for European Policy Analysis, pp. 1-71.

Papacharissi, Z. (2002). The virtual sphere: The internet as a public sphere. New Media & Society, 4(1), pp. 9-27.

Prier, J. (2017). Commanding the Trend: Social Media as Information Warfare. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 11(4), pp. 50-85.

Wierzejski, A. (2016). Information Warfare In The Internet: Exposing and Countering Pro-Kremlin Disinformation in the CEEC. Centre For International Relations, pp. 1-34.

Venturini, T. (2019). From Fake to Junk News, the Data Politics of Online Virality. In D. Bigo, E. Isin, & E. Ruppert (Eds.), Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. Routledge, pp. 123-44.