Dots, diamonds, and death - how Damien Hirst improves democracy

When someone talks about art, you might not immediately connect it with the functioning of a democracy. However, these two are more than connected. This dependency can be more comprehensible when seen in a photography series (Messinis, 2019) or carried out as an artistic statement on the current migration issue in the EU (Tondo & Stierl, 2020). But it can also be more subtle, inviting the public to start thinking about or discussing issues, values, or norms. I am curious how an art object can do that. A conceptual artist who is often criticized for his art, his way of creating, and his wealth is Damien Hirst. Hirst is known as one of the most influential artists of the contemporary art scene and his ability to shock the public with age-old thematics like mortality and death (Art Salon Holland, n.d.). So I wondered, “how does a conceptual artist like Damien Hirst contribute to democracy?”.

Damien Hirst who?

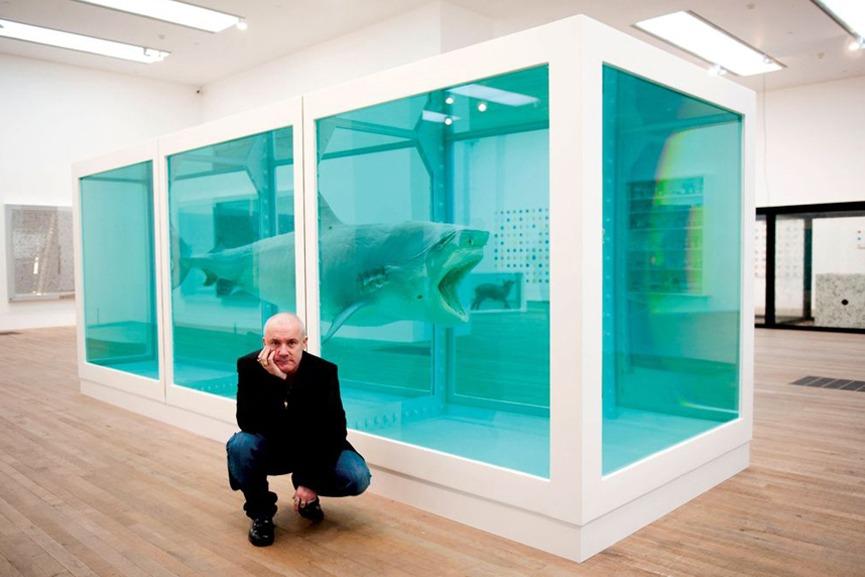

As YBA (Young British Artist) with a conceptual background (Vogel, 2006), Damien Hirst became well known with his piece The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living, which is an installation holding a four-meter long tiger shark. Throughout his career, he receives a provocative, unworthy and greedy image (Mount, 2012; Russeth, 2012; Vogel, 2006; Willett-Wei, 2013) after ‘stunts’ like A Hundred Years, For the love of God, and Beautiful Inside My 12 Head Forever. On top of that, from 1999 up to 2007, the artist has been accused six times of 3 committing plagiarism. Nowadays, according to the Sunday Times (2020) Rich List, Damien Hirst is the British wealthiest artist with a network of €363 million. As you can imagine, this number does no good for anyone already thinking negatively of Hirst.

The big discourse surrounding Damien Hirst is whether he can be considered an artist. Many accuse him of being a fraud for the fact that he is not producing his art himself (Russeth, 2012; Willett-Wei, 2013). What is so interesting about this is, that this is not something new. However, we seem to fall over this again in the current generation. Earlier, famous and praised artists like Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol had the help of assistants or factories too (Willett-Wei, 2013). Hirst explained, it is the intention that weights heavier, rather than the art piece itself or its execution (Vogel, 2006). For him “conceptual art is the art [that] does not exist in the object itself. It exists in the mind of the viewer. The art becomes just a trigger to set something off, which is the art, the conceptual art” (Hirst as cited by The Guardian, 2012a).

The big discourse surrounding Damien Hirst is whether he can be considered an artist

His work is all about investigating and challenging the contemporary belief system, and breaking up tensions and uncertainties at the heart of human experience (Hirst, n.d.a), and with that the definition of an artist and the demand of creation.

Agonism, a new perspective on democracy

To answer the question above — “how does Damien Hirst contribute to democracy with his art?” —, we need to create a general understanding of how our democracy works and how art can intervene in such. First, we will take a look at the theory that focuses on the different possible functions of a healthy public sphere, written by Chantal Mouffe (2013). The public sphere is a vital element of a strong and healthy democracy, as it ensures that its citizens are free and treated equally via opinions and ideas that contribute to forming a general agreement (Mckee, 2004, p. 8). The commonly accepted view of our public sphere is one “where one aims at creating consensus” (Mouffe, 2013, p. 107). Consensus is a concept often used by modernists and means “an exchange of arguments constrained by logical rules” (Mouffe, 2013, p. 25) or, in other words, a mutual agreement on something. Mouffe explained, however, that unlike the hegemonic aim for consensus, politics can only ensure equality via an agonistic approach (Mouffe, 2004, p. 21).

Whereas consensus is eliminating or relegating perspectives to establish a rational consensus, agonism is embracing all perspectives by mobilizing them and therefore “creating collective forms of identification around democratic objectives” (Mouffe, 2013, p. 23). The actual confrontation between competitors, exactly what consensus avoids, “is what constitutes the ‘agonistic struggle’ [and] that is the very condition of a vibrant democracy” (Mouffe, 2004, p. 21). Therefore, we could say that we should not aim for a modernist perspective, but for equality, and thus agonism, in the public sphere to contribute to a strong democracy.

Secondly, we will have to look at how art precisely can intervene some- or anything. According to Tate (n.d.), “the term art intervention applies to art designed specifically to interact with an existing structure or situation, be it another artwork, the audience, an institution or in the public domain”.

Since the 1960s, some art attempts to radically transform society in some way (Tate, n.d.). When we look at the concept we introduced above, the agonistic approach in politics, we have now defined how to connect and in what way art (intervention) is improving democracy. As art intervention introduces new confrontations or perspectives, it can add to the redefinition of a given hegemony and common sense of a society (Mouffe, 2013, p. 105).

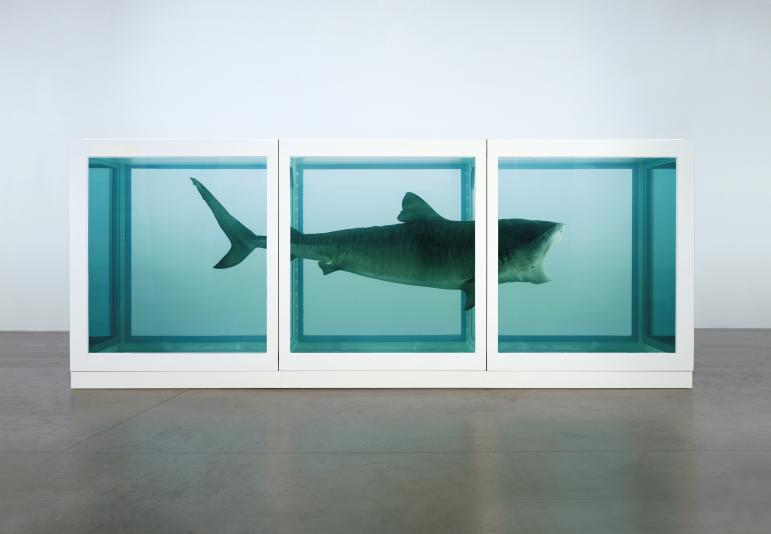

Figure 1 : The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living by Damien Hirst (1991)

Catching big fish

To see whether Mouffe’s theory applies to conceptual art, I would like to look at Damien Hirst’s piece The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living (see Figure 1) and analyze if and in what way this adds to democracy via intervention.

As explained before, The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living is one of Damien Hirst’s first successful art pieces, created in 1991, and became an iconic symbol to represent Britart worldwide (Davies, 2005). The installation consists of “a thirteen-foot tiger shark preserved in a tank of formaldehyde, weighing a total of 23 tons” (Hirst, n.d.b). As the title suggests, the piece is about how we, living subjects, have trouble imagining, expressing, and comprehending death (Hirst, n.d.b), even when confronted face-to-face with it. Introduced in a gallery setting, the (dead) shark is able to frighten us and therefore it lends Hirst the opportunity through which he can make viewers explore their greatest fears through artistic artwork or even commodity (Hirst, n.d.b).

In need of attention or creating intervention?

To find out if The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living is able to intervene in the democratic consensus, we have to look at the intention of the artist. According to the given definition of ‘art intervention’ earlier and Hirst himself, the intention of the artist to intervene counts as decisive to being an art intervention. To find out what Hirst’s intention is and determine whether this specific artwork can be considered an intervention, we will be analyzing and referring to earlier statements Damien made on this piece. According to Delikat (2017, p. 19), “Hirst’s intent [for all his art] is both to evoke and to provoke the viewer to think actively and engage with the works”. For the selected artwork in specific, “the imperative was to bring this moment of realization that death is inevitable” (Delikat, 2017, p. 3). According to The Guardian (2012b), Hirst made people look, “at objects in new ways, an important aim for any artist” and the goal of any intervention. Given the above quotations, we can conclude Damien intends to intervene, but then, how and in what ways is it able to?

First, it makes us think about what art is and when something is considered art. Damien is not the first, nor the last to create discourse around this definition. Before him, well-known artists like Duchamp, Warhol, and Koons did so in a similar manner (Delikat, 2017, p. 24). Nowadays, Hirst is being accused of creating not art but an exhibit for a natural history museum or “the desire for [making] it pathological” and therefore “a tragic depreciation” (Robert Hughes cited by Kennedy, 2004). Others claimed a lack of creativity or skill since ‘anyone could do this’ (Barber, 2003). His answer: “but you didn’t, did you?” (Barber, 2003) is emphasizing the necessary criteria of intention for something to be art. In a Tate Interview with curator Ann Gallagher, Damien explained how he loves that art can confuse or make someone doubt something (Tate, 2012, 05:56). His broadening of the concept of art comes from his desire to create art that could be understood by and communicated to the masses (Delikat, 2017, p. 25). How he does that is by creating an art object that stimulates interpretation. We are allowed or even encouraged, to complete the art piece by formulating our understandings and interpretations.

Secondly, it questions our understanding of how we receive art. Hirst explained in an interview (Hirst & Obrist, 2008), that art is often received as immortal. However, the artist shows us how this is and isn’t applicable to all art. By encasing a shark, he showed us the possible mortality of art. He chooses a shark because “he wanted something 'big enough to eat you' - something that, alive, would have been terrifying and, even in death, is not a comfortable company” (Barber, 2003). Since the original shark started decaying, it lost this power to scare (Hirst & Obrist, 2008) and therefore its conceptual meaning (Vogel, 2006). However, for Hirst, replacing the shark was no problem. He believes anything is replaceable (Hirst & Obrist, 2008) and for conceptual art, the intention is all that counts (Vogel, 2006): “We’re dealing with a conceptual idea,’’ he said, “the whole point is the boldness of the shark” (Damien Hirst as cited by Vogel, 2006). Another aspect emphasizing its immortality is the choice to preserve the animal in formaldehyde, meant to keep the impact and viciousness of the shark intact.

But most importantly, the artwork intervenes in our common perception of mortality and death. In our current western society, death is something often considered morbid or taboo (Lounsbury, 2014; Hannig, 2017; Li, 2018). It is associated negatively and only talked about in the past tense. For example, all the soldiers we lost in a World War and how a plague epidemic caused many weaklings to die. We are actively avoiding the topics of dying or grieving at all times (Hannig, 2017; Li, 2018). However, this has not always been like this and some people are striving to open up the conversation again nowadays (Hannig, 2017). In order to let loose the idea that death is a failure, societies need to break the silence and allow exploring someone's relationship with it. For example, start giving lessons in schools about the topic. When we start talking about death, it could lift possible anxiety, make us acknowledge and accept the inevitable (Hannig, 2017) and give us an “imperative for action” (Lounsbury, 2014). The latter, emphasizes the goal of life: enjoying it while we can and stopping wasting time.

This unjust idea of death and illness formed the current landscape in which Hirst created his art. With the “spectacular progress of medical science and pharmaceutical research” (Delikat, 2017, p. 16), our society is obsessed with “staying healthy and not dying” (Delikat, 2017, p. 16). Because he was fascinated by death and his earlier close work with corpses, Hirst discovered his talents as an artist. As result, Damien is trying to communicate life experiences, including his childhood experience of realizing his mortality as a child (Delikat, 2017, p. 17) via his art. He acknowledged having formed an obsession with death, but instead of morbidity, the artist sees it as a celebration (Delikat, 2017, p. 19). Just like Lounsbury (2014) explained before, Damien is hoping to communicate our mortality as something positive in his art. He explained: “Hopefully, thinking about it [death] makes you live your life more fully” (Delikat, 2017, p. 19).

The topicality of Hirst in times of crisis

When we take into account the current image of death in our western society, we clearly see how Hirst is contributing by, instead of hiding, confronting, and enlightening us with a new perspective towards death. Just like the example Mouffe (2013) uses in her theory, Hirst is “using resources which induce emotional responses, they are able to reach human beings at the affective level” (Mouffe, 2013, p. 111). By creating a simulation of a frightening situation, Hirst is able to speak to our emotions and influence our thoughts. To the extent of reaching a sense of sublimity, as it is “both putting death at a distance and bringing it closer with an appreciation of life” (Delikat, 2017, p. 20).

This case study proves intervention to be important. By promoting a devious perspective, in this case, the beauty of mortality and the inevitability of death, the artist aims to lift this taboo from our current public sphere (Li, 2018). By intervening, Hirst is promoting agonism instead of consensus and therefore aiming for equality (of ideas and perspectives) which, according to Mouffe, contributes to the strength of a democracy (Mouffe, 2004, p. 21).

In addition, this specific intervention can also help us in our current time of crisis. Now COVID-19 is taking over our thoughts in everyday life, we are confronted with our mortality more than ever (Jones, 2020). As “Hirst’s classic art keeps screaming the fragility of all organic matter” (Jones, 2020), it can help us redefine our negative perception of death into something more comprehensive and light (Hannig, 2017). As studies showed that COVID-19 had a global impact on mental health, due to increased feelings of anxiety, depression, and self-reported stress (Delmastro & Zamariola, 2020), I think that would benefit those to take a moment to consider a (re)definition of death. Only interventions like these can help with that. If we are never to stumble upon perspectives that differ from the norm and aim for the modernist's consensus, we can not develop onward and stay stuck and languish in a time where death is undeniable.

All in all, we can say that art — and especially conceptualism — has the power to shift perspectives, “perceive new possibilities” (Mouffe, 2013, p. 111), and improve the agonism, confrontation, and debate in our public sphere. Which is ensuring more plurality and equality in our public sphere and therefore directly linked with a strong and healthy democracy. Whether The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living makes you think negatively of Hirst or not, it made you question and discuss something — “is this even art? Why does it frighten me when it is fake? Why do we consider mortality as something negative?" — and that is exactly the point.

References

Art Salon Holland. (n.d.). Damien Hirst (1965).

Barber. L. (2003). Bleeding art.

Davies, S. (2005). Why painting is back in the frame.

Delikat, D.M. (2017). Facing mortality: Death in the life and work of Damien Hirst.

Delmastro, M., & Zamariola, G. (2020). The Psychological Effect of COVID-19 and Lockdown on the Population: Evidence from Italy.

Hannig, A. (2017). Talking about death in America. An anthropologist's view.

Hirst, D. (n.d.a). Biography.

Hirst, D. (n.d.b). The Physical Impossibility Of Death In The Mind Of Someone Living.

Jones, J. (2020). Damien Hirst review – just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water.

Lounsbury, L. (2014). Young people are dying to talk about death.

McKee, A. (2004). The public sphere: an introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Messinis, A. (2019). Life in a Greek makeshift migrant camp - in pictures.

Mouffe, C., Wagner, E., & Mouffe, C. (2013). Agonistics: thinking the world politically. Verso.

Mount, H. (2012). The man who dared to tell the truth about the charlatans of modern art.

Russeth, A. (2012). 11 opinions about Damien Hirst.

Tate. (n.d.). Art intervention.

Tate. (2012). Artist Damien Hirst at Tate Modern | Tate [YouTube video].

The Guardian. (2012a). 'I totally did away with the past': Damien Hirst looks back on his life in art - video.

The Guardian. (2012b). Damien Hirst: the artist we deserve.

The Sunday Times. (2020). Damien Hirst net worth - Sunday times rich list 2020.

Tondo, L. & Stierl, M. (2020). Banksy funds refugee rescue boat operating in Mediterranean.

Vogel, C. (2006). Swimming with famous dead sharks.

Willett-Wei, M. (2013). People are furious with Damien Hirst for not making his own art.