Deconstructing the 'Kapsalon'

In this article, I will deconstruct the 'kapsalon shoarma'. I will argue that the kapsalon can be read as an index of superdiversity.

The shoarma kapsalon as a byproduct of superdiversity

On top of providing the necessary nutrients that our bodies need to survive, food carries with it imperative associations as it is molded by divergent geographical, social, psychological, religious, economic and political dynamics (Demetriou, 2012). As such, when I walk into Didim Doner Pizza, a snack bar run by Turkish immigrants located at Besterdring 41, to purchase a kapsalon shoarma, I am, in fact, consuming a byproduct of superdiversity (Didim, n.d).

Created in Rotterdam, the kapsalon shaorma consists of crispy French fries and generous doses of fried lamb meat, sambal, garlic mayonnaise, melted cheese and bits of lettuce

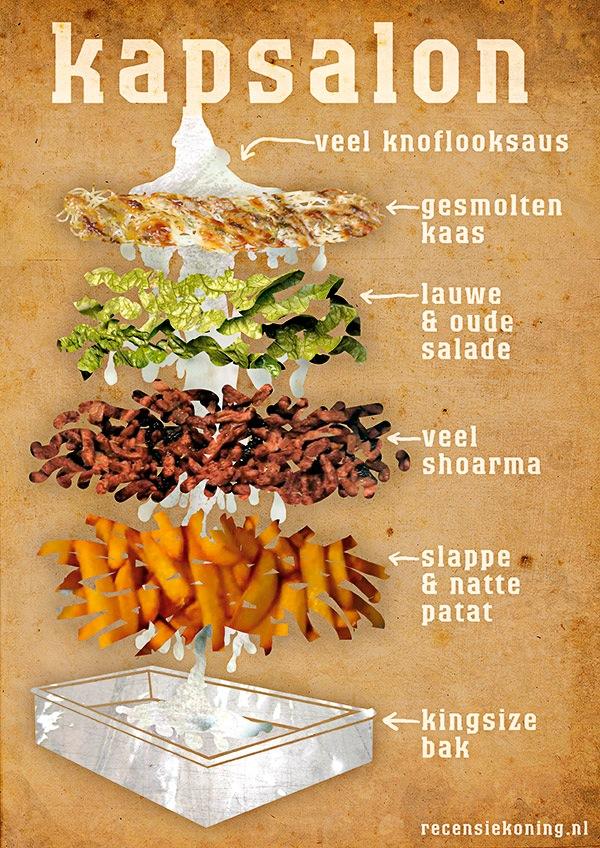

According to Vertovec (2006), super-diversity, is “the diversification of diversity” and it comprises of “an increased number of new, small and scattered, multiple-origin, transnationally, connected, socio-economically differentiated and legally stratified immigrants” and the features that come alongside with it. In deconstructing the dish, I contend that this definition by Vertovec places the kapsalon in category of superdiversity. Created in Rotterdam, the kapsalon shaorma consists of “crispy French fries and generous doses of fried lamb meat, [...] sambal (thick spicy sauce), garlic mayonnaise, melted cheese and bits of lettuce” (Goemans, 2008) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Kapsalon shaorma.

How to make a kapsalon shaorma?

In order to make a kapsalon shaorma, one needs to build several layers, starting with:

- slappe en natte patat [soggy french fries]: The origins of french fries can be traced back to late1600s, Belgium (National Center for Families Learning, 2015). During World War I, American soldiers stationed in Belgium gave these fried potato slices a sobriquet, french fries, due to the fact that the official language of the Belgian Army was French (ibid).

- salade [salad]: Invented during the days of the Roman Empire and introduced to its territories during its worldwide reign (Allan Doherty, 2009).

- knoflooksaus [garlic sauce]: It can be traced back to Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D), the Roman procurator in Tarragona (a city located in the south Catalonia, on the north-east of Spain) who wrote of garlic in his first century book Naturalis Historia (Stradley, 2004).

- sambal, which usually contains over 75% [of] chillies and has its origins in Indonesia, which was once a colony of the Netherlands (Meijer, 2012).

- melted Gouda cheese: Named after its place of origin, Gouda, and dating [back] to the 12th century, this semisoft cow’ milk cheese is described to be a great melting cheese which is perhaps why it is used as the cheese for this dish (Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 2015; Samuelson, 2012).

- شاورما or shoarma [as written on the menu of Didim Tilburg] can also be found.

شاورما, shoarma, shawarma, shwurma or döner?

Shaorma has its origins in Anatolia, Turkey, from the 18th century (The Kebab Shop, 2015). It comes from the Turkish term ‘cevirme’, meaning ‘turning something’ to describe a chef turning the rotisserie by hand (The Kebab Shop, 2015). With the rise of technology, the rotisserie now rotates on its own, and as such, Turks [call] it ‘döner’ whereas Arabs [continue to refer to it as] ‘shawarma’ (The Kebab Shop, 2015). Apparently, other than the name, there are no real differences between [the] shawarma and döner (ibid). It is also called gyros in the Greek cuisine, tarna in Armenian and guss in Iraqi cuisine (Everything.Explained.Today, 2015). Although the store, Didim Doner Pizza, is run by Turkish immigrants, it is named in this Arabic form, shaorma, on the menu.

The very existence of the kapsalon is a clear explication of layered and fractured diversity, defying conventional images of languages, groups, and competence.

There are a variety of ways in which one can spell the word شاورما including, shawarma, shoarma, shwurma, among others. This is indicative of the repositioning of minority languages and in this sense, strictly local as a social tool. If the word was written in Arabic, most people in the Netherlands, for instance, would probably not be able to read or understand it. The very spelling of shoarma, as observed in the menu of Didim Doner Pizza, is a means of de-globalization and makes sense within local conditions, in terms of the Dutch pronunciation of the word. It could be dramatically wrong, but one is still able to communicate effectively what it is. The small features have become globalized and no matter the spelling of the word, people all over the world have an idea of what shawarma or shoarma is. As such, with this principle, the very spelling of the word shoarma in Didim Doner Pizza’s is a clear explication of a word that could be linguistically wrong but pragmatically right. It showcases the perpetual mobility of sociolinguistics (Blommaert, 2013).

Institutional scenarios constantly hammer on the terms ius soli and ius sanguinis to describe nation states’ view on the issue of integration (Blommaert, 2013). If this definition were overarching and true, considering the international features of this dish, then how can Rotterdam consider the kapsalon to be one of her defining features of her identity?

With globalization came the mobility of goods, value, power and people. The flow of knowledge, ideas, culture, methods(that are considered to be the defining characteristics of a certain country or culture or city would have never been available without globalization. The kapsalon shaorma is an exampleof the aforementioned.

Super-diversity and fusion

With superdiversity comes a new field of language variation (ibid). One has to debunk and challenge standard assumptions, notions and models of how language and culture are static and realize that they are unstable, flexible, mobile and are dependent on factors of scale (Blommaert, 2013). As communities are transitory and ever-changing, so are languages. By looking at the kapsalon shoarma, it is indicative of how every synchrony is a nexus of varying histories and the meaningful science that incorporates all kinds of conditions.

The very existence of the kapsalon is a clear explication of layered and fractured diversity, defying conventional images of languages, groups, competence, to name a few, as it is a complex synchronization of cultures coming together as well as the layering complexity of meaning effects.

Ultimately, this dish, and many others like Hawaiian snack spam musubi, Canadian butter chicken wrap and the Dutch shoarma pizza are products of a mishmash of cultures that can be made possible only through the diversity of diversity.

References

Allan Doherty. (2009). “The Romans, Europeans and USA”. Retrieved from Gardemager.

Blommaert, J. (2013). "Language and the study of diversity". Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, Paper 74. Retrieved from Tilburg University.

Demetriou, C. (2012). “‘May this thesis be the stepping stone for accepting dissimilarities and creating healthy and productive intercultural relationships”, 36-42

Didim. (n.d). “Kapsalon”. Retrieved from Didim: Pizza & Shoarma- Doner Kebab & Turkse Pizza’s.

Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. (2015). "Cheese". Retrieved from Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Everything.Explained.Today. (2015). “Doner kebab explained”. Retrieved from Everything.Explained.Today.

Goemans, A. K. (2008). “Kapsalon: A Rotterdam Speciality”. Retrieved from Venere Travel Blog.

Meijer, B. J. (2012). “Sambal- A chilli condiment, the purest use of chillies!”. Retrieved from growing, tasting and using chillies.

National Center for Families Learning. (2015). “Wonder of the Day #24: Do French Fries Really Come From France?”. Retrieved from Wonderopolis.

Samuelson, E. (2012). “What is Gouda Cheese?- How It is Made Used”. Retrieved from Ea Like No One Else: Your Guide to Making Good Choices at the Store for Better Food at Home!.

Stradley, L. (2004). “Sauces- History of sauces”. Retrieved from What’s Cooking America.

The Kebab Shop. (2015). “Story”. Retrieved from The Kebab Shop.

Vertovec, S. (2006). "The emergence of super-diversity in Britain". (Working Paper No. 25). Retrieved from COMPAS: Centre on Migration, Policy & Society.