Digital Superhero Comics vs. Coronavirus: the comic book industry in times of COVID-19

The long quarantine period owed to the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 has made the world a testbed for remote work and education, virtual socialization, and online entertainment. Several companies and individuals in the cultural sector have allowed free online access to their creations. Paywalls were temporarily lifted on online books, news, concerts, lessons, films, music, TV shows, and other mass cultural products as disruption in commerce was felt in all industries, markets, and areas. The so-called "comic book industry" was one of those that were hit hard.

Having emerged in the late 1930s, the Superhero genre is of great relevance to this industry, being not only the first comic genre to be conceived directly in other media instead of newspaper strips, but also the consistently dominant genre in American comic books since the 1960s. The continuous transmediatic adaptation of its characters and plots - from 1940s radio shows to live action streaming series, and everything in between - places it in a unique strategic position for providing diverse content to the multi-billion-dollar entertainment industry.

A boost to digital superhero comics

The digital superhero comics market received a relevance boost during the last week of March 2020. The main Superhero comic book distributor in North America, Diamond Comic Distributors – the sole distributor of comic books for Marvel Comics, DC Comics, Image Comics, Dark Horse Comics, and other major and minor publishers in the US since the mid-1990s – was forced to suspend its shipments to comic shops due to economic, regulatory, and public health reasons. This meant that approximately 2,000 comic book speciality stores in the country, which were already working in reduced capacity, dealing with the absence of customers on the streets and government shutdown orders, as well as another 500 outlets in Canada and the United Kingdom, would not have new products in the foreseeable future.

Comic shops not only remain the largest outlet channel for comics, but have also been the most lucrative for Superhero publishers since the 1980s.

Most comic book publishers worked out ways to reduce the financial damage retailers would undoubtedly suffer. Initially, the two largest companies in the industry, Marvel and DC, reacted by, respectively, establishing big discounts for retailers and making recently acquired products returnable. Publishers Image, Dark Horse, Dynamite Entertainment, IDW Entertainment, BOOM! Studios and Oni Press also applied return policies and reduced their output of publications as well. But on that last week of March, most comic book companies released their digital editions as scheduled, with a few notable exceptions: publishers Dark Horse, Valiant Entertainment, BOOM! Studios, AfterShock Comics and creator Erik Larsen, of The Savage Dragon (published by Image), refrained from releasing digital issues of publications that were not available in print editions. Although a statement from DC stated that their data showed that “the digital consumer and the physical consumer are two different audiences”, industry analysts and comic shop owners believed this turn to the digital format might stir a section of print comics readers towards digital issues, maybe even permanently. This is a concern that has been shared amongst the entire publishing industry to varying degrees.

Becoming a sizeable market

Despite being relatively new - the first webcomics came out in the mid-1990s - digital comics have rapidly developed into a huge business. In the last few years, the digital comic book industry has been responsible for an average 10% of annual comic book and graphic novel sales in the US and Canada. In 2018, this meant 100 million dollars, out of a total of US$1.095 billion. The primary company of cloud-based digital distribution of comics, comiXology, currently offers 75,000 titles from more than 120 publishers, in a hybrid of the film and music business model formats. Acquired by Amazon in 2014, it reports over 200 million comic downloads in the last decade, and these numbers do not even include Chinese comics nor the great majority of Japanese digital Manga. Two years later, the company launched comiXology Unlimited, an online subscription service that gives access to over four thousand issues of comics for a monthly fee of less than the price of two print comic books.

Still, comic shops not only remain the largest outlet channel for comics, but have also been the most lucrative for Superhero publishers since the 1980s. Until the mid-1970s, comic books were mostly sold on consignment through newsstands and shops that would feature magazine racks, such as drugstores and supermarkets. It was a distribution system that made publishers overprint over two times what was sold. Reed Tucker (2017, pp. 133-138) reports that the late 1960s advent of comic book speciality stores enabled the development of a more cost-effective channel for publishers in the mid-1970s, since the discount sales to these establishments have always been non-returnable. This would become known as the Direct Market. [1]

Saving print comics

It is understandable that in the present circumstances the industry would reach out to help its money-making backbone. After being frowned upon for maintaining the schedule of its digital editions, Marvel soon joined the other publishers who had ceased the release of any new comic books digitally or in print, and paused 15% to 20% of the work on its ongoing titles, delaying their schedules. DC Comics, the second largest Superhero publisher - with 33% of the market, against Marvel’s 37% - donated US$250,000 to the non-profit organization Book Industry Charitable Foundation (BINC) "to provide support for comic book retailers and their employees during this time of hardship and beyond".

The concern the Direct Market felt that print comics buyers could be permanently driven towards digital editions even prevented a hybrid solution from being adopted.

Generous financial support also happened at personal levels: comic book writers Donny Cates and Kevin Smith, for instance, paid for entire batches of pre-ordered comics that local stores in their hometowns had reserved for customers, so that the retailers could get cashflow they were counting on. Financial relief for comic shops also made its way through the online engagement of comic book creators.

In early April, DC's Chief Creative Officer and renowned artist Jim Lee started daily auctions on eBay of more than 60 original sketches of DC characters, also joined by other authors, such as Superman’s current artist Ivan Reis and Marvel’s veteran Arthur Adams. A few days later, comic book writers Sam Humphries and Brian Michael Bendis, currently at DC’s imprint Wonder Comics, initiated the hashtag #Creators4Comics on Twitter, getting over 250 creators to individually auction original artwork, commissioned stories, signed books and toys, rare editions, and several kinds of services (from podcast interviews and online classes to portfolio reviews and script critiques) to benefit BINC.

In early April, the implementation of a temporary distribution method was announced involving ComicHub, a point-of-sale system, already in use, that enable readers to purchase publications from physical comic book shops online. The plan was to allow publishers to upload full digital copies of comic books - instead of only a few preview pages, as is currently done - to give readers immediate access to these titles, paying directly to the retailer.

Once distribution was restored to normality, the digital copies could be exchanged for printed ones in the local stores they were bought from. This meet-me-halfway solution would attend to the needs of publishers, comic shops and readers, by respectively allowing them to release, sell and read new comic books, without causing major financial losses to the stores nor hurting collectors’ needs. But the initiative was quickly dismissed a few days later, under the view that it would encourage “cross channel migration (even passively)”, as one San Francisco store owner put it.

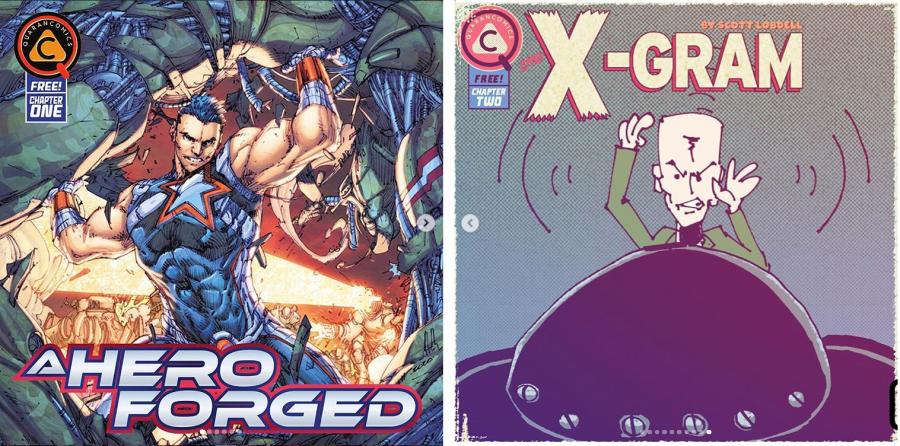

A Hero Forged by Scott Lobdell and Brett Booth & X-gram by Scott Lobdell on Instagram

New users, new formats

Jan Blommaert (2020) recently wrote that, due to the pandemic, “millions of people who had never come near online communication tools have become users almost overnight, out of sheer necessity”. Maybe reading Superhero comics does not exactly qualify as a "necessity", but the lockdown measures have definitely created opportunities and motivation for reticent non-users to at least experiment with digital publications. From independent creators to established publishers, all types of stakeholders in the comics industry have offered thousands of digital issues of their comics to be freely downloaded as PDFs or read online. ComiXology, for example, doubled their regular free trial period for comiXology Unlimited, from 30 to 60 days. Comic book talent agency Chiaroscuro Studios allowed free download of an original Superhero graphic novel produced by fifty of its represented artists in 2017 as the agency’s annual portfolio. Even comic-related publications - like the digital edition of Josh Blaylock’s book How to Self-Publish Comics and Thales Martins’ e-books on Superhero comic book characters Jessica Jones (from Marvel) and Preacher (from DC Comics imprint Vertigo) - were offered as free downloads. Not ignoring the altruistic aspects of giving out free goods in the middle of a complex and stressful time, there are also many different factors at play in this at the moment, from gaining peer recognition and social media visibility to unequivocal business opportunities.

Free digital issues have always existed, mostly as samples, following the same logic used in the marketing of print comic books: as first issues or origin stories to captivate readers’ interest, or old issues as part of a discount or promotional bundles. This recycling aspect of the comics industry plays a strategic role during the current crisis. In 2018, DC launched a 100-page print anthology comic book line called DC Giants, compiled of both new stories and reprints of various classics from the publisher’s archives. As the comic books were exclusively sold at Walmart chain stores, its new stories were not digitally available. A few weeks into the pandemic distribution halt, DC repackaged them for free daily releases within their Digital First line. The production of digital-first comics may also see a temporary increase during the pandemic due to reassignments of creative teams previously working on print titles that were temporarily paused.

Transmedia connections

The term "digital-first" refers to comics released in digital format before eventually reaching print. Since 2011, DC has been the major publisher to pioneer this distribution method, developing direct-to-digital comic series as tie-ins to TV shows (such as Smallville, Batman ‘66, Arrow, Flash), cartoons (Teen Titans Go!, DC Super Hero Girls, Batman Beyond, Scooby-Doo Team-Up), feature films (the Dark Knight trilogy, Justice League) and videogames (Batman: Arkham City, Injustice: Gods Among Us), all media formats that often present plots and characters slightly different from those seen in regular comic book continuity. Digital-first issues also tend to be shorter and cheaper than a print comic book, selling for US$0.99 each. Once successful, these mini chapters can be repackaged into print comic books or collected hardcover editions. In that sense, Superhero digital comics are considered something of a complementary strategy to print comics, either serving to test ideas, products or untapped audiences that could get proper attention if it pays off, or as cost-free promotional tools.

The crisis has also inspired Superhero comics to explore formats and platforms where the genre is not regularly seen. For instance: independent comic book author Daniel Arcos started producing podcast adventures of his superhero creation Rboy, tied to the character’s comic books, in the manner of a 1930-1940s radio series. Superhero comic book writers Scott Lobdell and Frank Hannah, currently working on DC Comics titles, started producing and publishing independent comics on Instagram “to offer free content to fans and readers stuck at home during the quarantine at a time where new comic books are scarce”. Lobdell, who had written some of the most popular and best-selling X-Men comics in the 1990s, is writing and drawing X-gram, an original and unofficial X-Men comic strip, published on Quarancomics twice a week. Quarancomics also feature superheroes in short animations and pin-up illustrations by several artists, as well as on another comic strip by Lodbell, A Hero Forged, drawn by Teen Titans comic artist Brett Booth.

Accessibility to a lot of content formerly available only to those that could afford attending comic industry gatherings has also been expanded, even democratically leveled.

It is also worth mentioning that accessibility to a lot of content formerly available only to those that could afford attending comic industry gatherings has also been expanded, even democratically leveled. As the great majority of comic conventions have been cancelled, a number of live virtual events have been taking place on YouTube, Instagram and other social media platforms, launched by event producers, publishers and other organizations or groups of individuals. A good example of the latter is the At Home Comic Con that was live streamed on April 16th, offering ten one-hour panels of everything Superhero - comics, film, video games, academic papers - raising US$7,500 in donations to help organizations fight the effects of COVID-19.

Comics go mobile

Perhaps the most relevant incursion the Superhero comics industry has experienced during this period, though, was becoming actively aware of the Mobile Comics format. Also known as “webtoons” - after South Korean pioneer platform Naver Webtoon, globally named as LINE Webtoon - this type of digital comics employs the Infinite Canvas approach first established by Scott McCloud in 1995, in which the comic is read by scrolling the screen, disregarding the concept of multiple pages, its layout structures or even individual panels. Today’s webtoons are published on one long vertical strip and read by scrolling down the smartphone screen, in short, weekly, episodes targeted to 15-to-25-year-olds. The average webtoon platform business model is to give free access to the first three episodes of each series and offer subscriptions that cost less than one print comic book per month. Although the Asian webtoon market is expected to be valued around US$894 million by the end of 2020, webtoons have only recently been introduced in Europe and the Americas, and they were virtually devoid of the Superhero genre until The Resistance.

The Resistance is the first title launched by AWA Studios, a new publisher founded in late 2018 by two professionals who have made a career at Marvel, Axel Alonso as editor-in-chief and Bill Jemas as vice president. The title was scheduled to hit the comic shops on the very week Diamond suspended shipments of new products. Ironically, the title introduces a new universe of superheroes that emerge all over the world after a global pandemic kills four hundred million people in two months. With the print edition failing to reach the Direct Market, AWA pulled out the digital edition from comiXology and made the debut number available on its website and mobile comics platforms WEBTOONS and Tapas.

Since then, each print issue of The Resistance and AWA’s subsequent titles has been divided into three or four episodes and released in that manner, with the publisher announcing its intention to expand the mobile comics line even after comic shop distribution is regularized.

The grammar and the business of comics evolved as it departed from the visual and thematic restraints of newspaper strips to occupy the comic book, over eight decades ago, and the birth of the Superhero genre embodies that change. Before learning how to fully embrace the possibilities of the new medium that was being developed as a consequence of powerful social changes and technological progress, the first comic books were produced by assembling unused newspaper strips - which makes a compelling analogy to how digital comics were simply digitized versions of print comics, until very recently. Now, the complex repercussions the COVID-19 pandemic presents seem to be establishing a massive stepping stone in an evolution that has been in motion for the last three decades.

References

Barnett, D. (2015, July 3). Comics capture digital readers – and grab more print fans. The Guardian.

Gustines, G. (2020 April 14). Comic creators unite to benefit stores. The New York Times.

Johnston, R. (2020 March 29). DC Comics on Digital Disruption of Distribution in Coronavirus Shutdown. Bleeding Cool.

Karlin, S. (2017 August 15). How Digital Comics pioneer comiXology keeps its identity within Amazon. Fast Company.

McCloud, S. (2000). Reinventing Comics. Paradox Press.

Miller. J. (2019 May 2). Comics and graphic novel sales hit new high in 2018. Comichron.

Park, J. (2019 September 20). Webtoons: The next frontier in global mobile content. Mirae Asset Daewoo Media.

Salkowitz, R. (2020 March 24). Final Crisis? Diamond Comic Distributors halts shipments of new comics in response to COVID-19 shutdowns. Forbes.

Tucker, R. (2017). Slugfest: Inside the epic 50-year battle between Marvel and DC. Da Capo Press.

White, M. (2012 August 12). A look around the Digital-First Comics landscape. Publishers Weekly.

Wilson, J. (2019 March 11). Comixology.com. PC Mag UK.

Notes

[1] Reed Tucker’s account of the creation and development of the Direct Market: “Marvel rang up US$300,000 in direct market sales in 1974, the initial year. That money would continue to grow, and by 1979 that US$3000,000 had ballooned to US$6 million. (...) Sales to comic speciality outlets accounted for 20 percent of the publisher’s sales in 1980. (...) In 1982, the direct market accounted for 50 percent of Marvel’s sales but 70 percent of the company’s profits, due to the higher prices on titles sold in comic shops and the nonreturnable nature.” (Tucker, 2017, pp. 136-138).