Digital vigilantism during COVID-19 : The Chengdu patient

In 2020, a sudden pandemic affected people's lives worldwide. As of now, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide has exceeded 84 million. COVID-19 has forced us to form many new social norms, such as wearing masks and maintaining social distancing. As one of the first countries to fight against the coronavirus, China has implemented strict prevention and control measures.

From contact tracing to digital vigilantism

From the beginning of the pandemic, the Chinese Health and Safety Administration has conducted epidemiological investigations into confirmed patients and publicly released information about their movements so that people can determine whether they need testing or home isolation. This ensures that close contacts hidden in the population can be tracked as soon as possible, reducing the risk of virus transmission.

However, while this transparency effectively controls infected patients' contact population, it has alaso incited anger towards infected patients that may have spread the virus by visiting public places. Online many people have condemned infected patients and even conducted human flesh searches for patients' true identities. These actions consitute digital vigilantism, which is “a form of mediated and coordinated action. Its point of departure is moral outrage or a general sense of offense taking, typically towards an act offenses been captured and transmitted via mobile devices and through social platforms" (Trottier, 2017).

Through a particular case of digital vigilantism towards a confirmed patient in China, I will analyze how digital vigilantes name and shame diagnosed patients through social media affordances and the impact of digital vigilantism on this case.

The Chengdu patient

On December 8, 2020, after the epidemic in China had been stabilized, the city of Chengdu suddenly reported four new cases. One of these cases was a twenty-year-old woman infected by her grandmother. The patient's activity trajectory was subsequently released by the news. She visited four bars and many other entertainment venues without a mask in the two days before her diagnosis.

In just those two days, she had close contact with 4,725 people according to the epidemiological investigation. Those people needed to be quarantined in hotels according to China's coronavirus policy. As soon as the news came out, many netizens felt panicked and angry, believing that the patient’s actions showed a complete lack of social responsibility and a failure to comply with public order during COVID-19.

The patient's private information was quickly uncovered and a variety of unrelated people became involved. It became a hot topic in just a few days. On Weibo, a Chinese social media platform, there were ten trending topics related to this patient with a total of more than 4 billion views.

In this article, I will focus my analysis on Weibo as most of the digital vigilantism process and vigilantes’ comments are concentrated on this platform, and there are both individual user comments and mass media reports about this case.

Human flesh searches and social media affordances

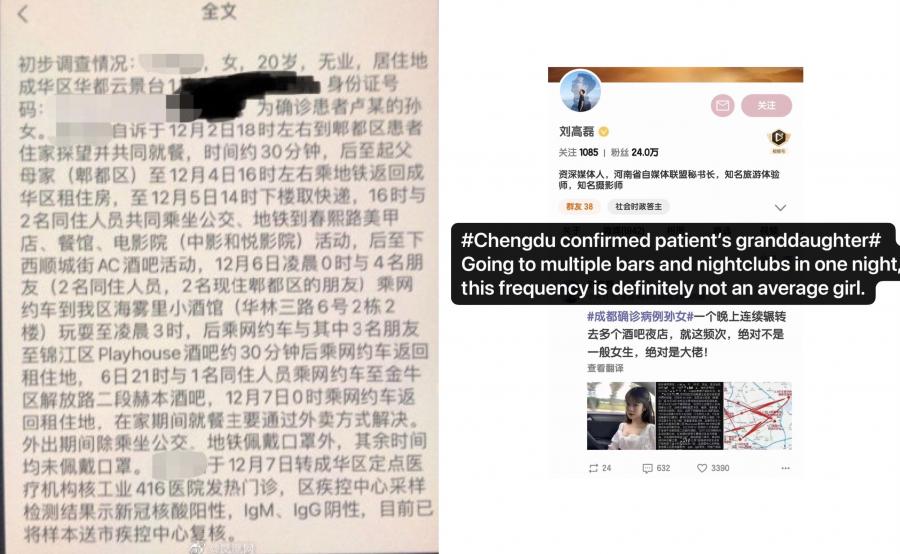

On the day the patient’s trajectory was announced, a senior media worker with 240,000 followers on Weibo posted a photo claiming that the girl in the photo was the 20-year-old patient diagnosed in Chengdu. This photo then went viral on the platform. Netizens spontaneously began looking for patient's identity through human flesh searches. Her private information, including her ID number, home address, and mobile phone number, were soon made public on Weibo.

figure 1. Patient's information was leaked

The human flesh search is one category of digital vigilantism, which has “the shared intention to expose shame and punish the deviant individual to reinstate legal justice of public morality” (Cheong and Gong, 2010). In this case, netizens searched for the patient because she entered multiple entertainment venues without wearing a mask during the epidemic and exposed thousands of people to the virus. This behavior occurred during COVID-19, when everyone anxious about the risk of infection; the patient's behavior made netizens angry and offended.

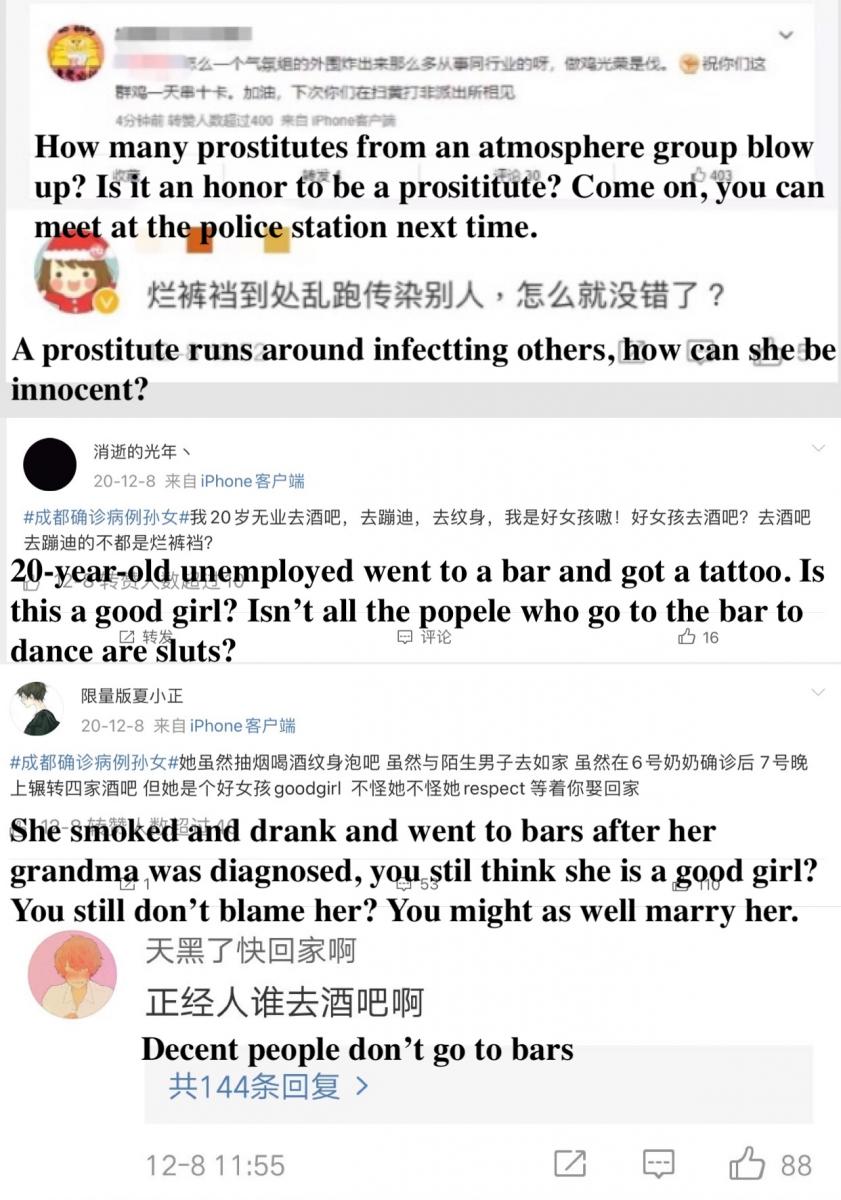

figure 2. comments under the topic

In the above example from Weibo, we can see that many netizens criticized the patient's lack of social responsibility. This criticism was quickly contextualized and transferred: “Online justice seeking involving shaming ‘is a social emotion in the sense that other people and institutions leverage it to control others.” Based on gender stereotypes prevalent in Chinese society, many digital vigilantes used the fact that the confirmed patient was female to apply extremely conservative moral standards to her behavior.

Many comments state that going to multiple bars at night is inappropriate behavior for a young woman, and some netizens even insulted and vilified the patient with vulgar language. Because the unequal treatment of gender in Chinese society, the condemnation of the lack of social responsibility for confirmed cases was easily contextualized into specific abuse towards women.

Weibo, as a social media platform, has significantly aided the progress of digital vigilantism. Weibo users can freely edit their profiles on the platform, meaning they can comment anonymously. They are able to express any opinion without restrictions and without worrying about their offline life being affected.

At the same time, social media also provides the conditions necessary for human flesh searches. Social media users may post daily pictures to their accounts and mark the location in the photos. This inadvertently released information can be turned into a weapon when the public criticizes them: “This vigilantism includes, but is not limited to, a ‘naming and shaming’ type of visibility. This typically involves sharing the targeted individual’s personal details by publishing them on a public site, including sensitive details such as the target’s home address, work details as well as financial and medical information. The nature and source of this information may vary greatly and may also implicate family members and associates” (Trottier, 2017).

Digital vigilantes can rely on these clues to determine their targets' demographic and geographic information and then use this information to abuse and harass them. In this example, the young woman whose photos were exposed often shared daily photos on Weibo and had more than 140,000 followers. This visibility makes it easier for digital vigilantes to dig up more private photos and information before circulating this information widely on the platform, ultimately hurting this young woman’s reputation.

Furthermore, social media provides connectivity: “In a connective ecosystem of social media, the "platform apparatus" always mediates users' activities and defines how connections are taking shape...” (van Dijck & Poell, 2013). As a social media platform with high user vitality, Weibo can provide users with customized content, grasp the user’s social network relationships, and create groups and communities on the social platform by providing connections that associate users with specific content. All this helped bring attention to the Chengdu case.

Weibo uses a popularity ranking algorithm that allows influential users more visibility with content that conforms to popular trends. Generally speaking, breaking news or news with strong emotions will gain higher popularity. However in order to provide a better reading experience and ensure a complete content consumption ecology, Weibo also gives weight to other specific types of content, such as posts with multiple images, hashtags, or narratives with long text. The topics with the highest algorithmic popularity are displayed on Weibo's trending topic list.

As mentioned above, topics related to the 20-year-old Chengdu patient frequently appeared on the Weibo hot topic list, and the total number of views exceeded 4 billion. When news of the case was released, many citizens panicked, and the number of searches for related topics soared. As Weibo users learned about the patient's trajectory, panic turned into anger. Digital vigilantism helped keep the case on the hot search list. With this increased visibility, moral condemnation of the patient also accumulated and strengthened.

Marketing accounts on Weibo also significantly contributed to the case's notariety. Marketing accounts are accounts that attract user traffic through news and other information and then make deals with advertisers to obtain revenue. Marketing accounts are not professional news media accounts, so the content they publish does not have exact sources. They usually post information widely circulated on the internet based on hearsay evidence. However, because successful marketing accounts have a large number of followers, the content they publish will also generate a large amount of traffic, so it often appears in the hot content of the topic and plays a role in framing.

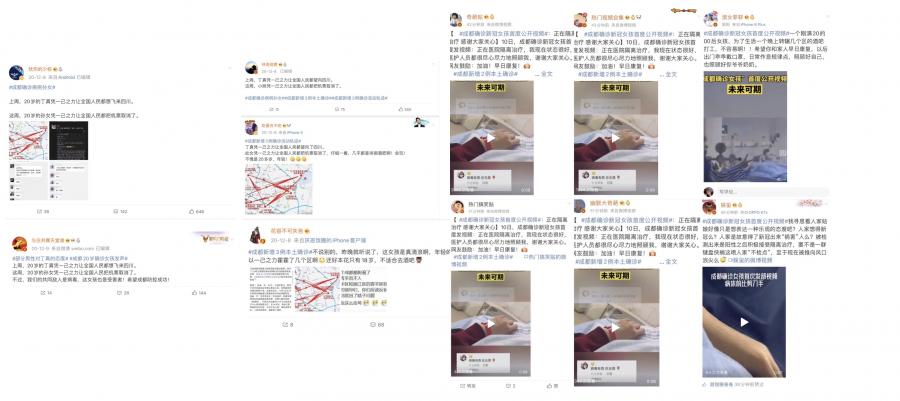

figure 3. Marketing accounts on Weibo

From the above example we can see that many marketing accounts post the same or similar content, videos, and pictures. However, these marketing accounts conveyed various meanings over time. Marketing accounts posted the pictures on the left when information about the Chengdu case were first released. The marketing accounts used a unified copywriting with attached patient trajectory maps. The text jokes that many people who planned to travel to Chengdu canceled their trips because of the reported cases.

On the right are the marketing accounts' posts following a public apology from the patient stating that her life and reputation were affected. The marketing accounts' attitude changes significantly between posts: instead of a joking tone, the second is a cheer for the confirmed patient and wishes her a speedy recovery. Marketing accounts' power on Weibo drove the framing of public discourse online and ultimately contributed significantly to digital vigilantism.

Effects of digital vigilantism

However, the great amount of attention paid to this topic does not mean the information reported was accurate. Soon after the photo of the alleged 20-year-old Chengdu patient went viral, the person in the photo refuted the rumors, stating that she was not from Chengdu and was not diagnosed with coronavirus. The photos were misappropriated, and her life was greatly affected by the rumors and negative comments online. By the time she was able to refute the rumors, the damage was already done.

figure 4. Fake news on mass media's Weibo account

Emotion is a critical piece of social media's infrastructure, and content rich with emotion can attract clicks and user participation to a certain topic. Importantly, for digital media, users’ clicks can be converted into profit. In today's high-speed online information flow, it is very challenging to provide users with attractive and profitable content that is also timely. Therefore many news accounts on Weibo did not have enough time for fact-checking, resulting in false news reports.

In this case digital vigilantism had a negative impact. The average internet user is not a professional journalist, and Weibo users often do not have the time or ability to verify news sources before sharing them. The social media logic allows misinformation to spread on a large scale. This misinformation was eventually adopted by mass media, leading to the wrong target citizen and affecting unrelated people’s lives and reputations.

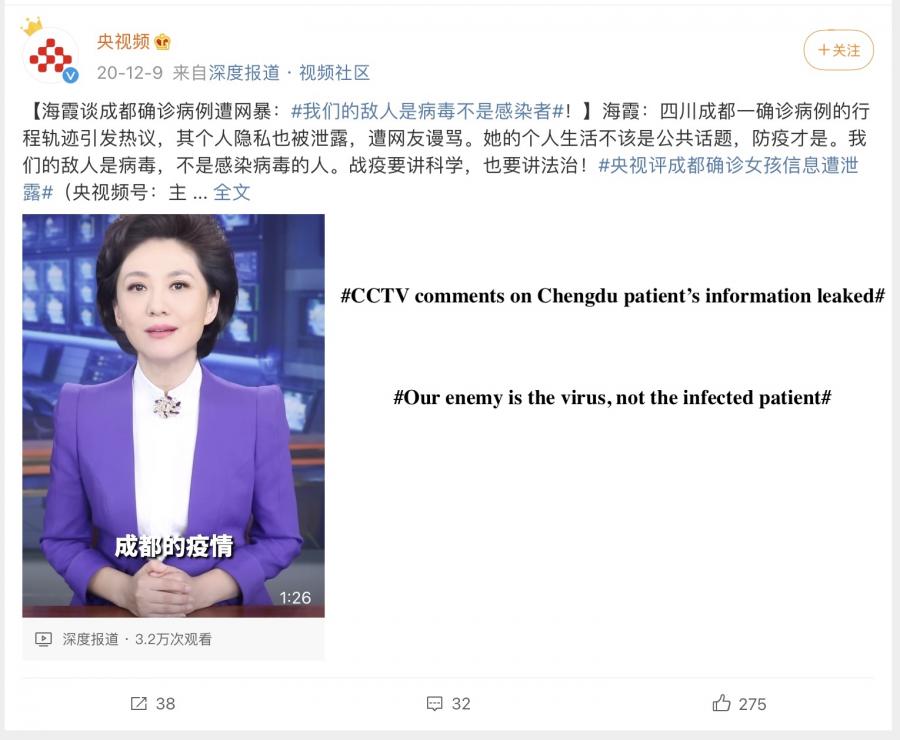

As the alleged Chengdu patient's personal information spread online, more and more Weibo users publicly abused the patient’s private life. The number of fake news reports also increased. The topic then attracted the attention of the Chinese official media and police. One of the hosts of China Central Television expressed that the exposure of personal information by human flesh search is illegal, and that the personal lives of patients should not be a topic of public discussion. The Chengdu police shortly issued a notice that the man who leaked the alledged patient's personal information had been held criminally responsible and given administrative punishment.

figure 5. Official mass media criticized digital vigilantes

Internet users' moral criticism of alleged patients was transformed into harassment about their personal lives. Such abuse gradually goes from justice-seeking to violent cyber bullying. The situation in Chengdu quickly spun out of control. Vigilantes leaked the patient’s private information through human flesh searches, greatly damaging the patient’s life and reputation. “Digital platforms have the potential to amplify that shame with very little opportunity to revoke it” (Allen & Zyl, 2020) All of these factors led this attempt at digital vigilantism to fail.

Through this case, it is not difficult to see that digital vigilantism has had many negative consequences: it spread false information, damaged the lives and reputations of unrelated persons, and leaked private information that led to the patient being abused and harassed. Because of the emotional infrastructure of social media, digital vigilantism often brings extreme anger and prejudiced accusations from netizens that can quickly spin out of control.

References

Allan, K., & van Zyl, I. (2020). Digital vigilantism, social media and cyber criminality. ENACT Africa.

Cheong, P. H., & Gong, J. (2010). Cyber vigilantism, transmedia collective intelligence, and civic participation. Chinese Journal of Communication, 3(4), 471-487.

Trottier, D. (2017). Digital vigilantism as weaponisation of visibility. Philosophy & Technology, 30(1), 55-72.

Van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Media and Communication, 1(1), 2-14.