How did fake news run voters' opinions in the Brazilian elections

In the second half of 2018, Brazil faced one of its most polarized presidential elections and fake news played a huge role. The confrontation got international attention even before the first round of voting, not only because of the huge dispute between left- and right-wing politicians and supporters, but also by the rising tide of fake news about both presidential candidates, Jair Bolsonaro and Fernando Haddad, all over the country. At the same time that social media increases the potential reach and speed with which fake news spreads, it is possible to notice a movement of traditional and international media to join forces and to use their own digital social media platforms to counteract the spread of false information.

Foto 1

Figure 1: Supreme Electoral Tribunal, the highest authority on election laws and regulations, tries to fight Fake News during the Presidential Elections, but without regulation by law.

Fake news

Understanding the idea of how fake news spreads so fast in contemporary society is a simple task. Studies show that people are much more likely to believe stories that favor their preferred candidate, especially if they have ideologically segregated social media networks (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017), which makes the perfect environment for the political circulation of fake news. However, this is not something entirely new: Brazil already faced a similar situation. For example, in the week that the opening of the impeachment of former President Dilma Roussef was authorized by law (in April 2016), three of five most shared news items on Facebook in Brazil were false, according to a survey by the Public Policy Research Group on Access to Information of the University of São Paulo (USP).

First, it is important to understand what fake news is. According to the TrendLabs Research (2017), fake news is the promotion and propagation of news articles via social media, designed to influence or manipulate users' opinion. Even though the term itself is not something new, due to globalization and the advent of social media, so-called “fake news” became increasingly common all over the world. In addition, the targeting and crowd dynamics created by social media allow ideas to spread faster and longer than ever before.

Famous political events like Brexit, the USA Presidential Elections in 2016, and the Brazilian Presidential Elections in 2018 are often related to fake news and manipulation of public opinion by academics. The concept of globalization that leads to the connectivity of digital platforms makes it possible to share and spread information in a way that was never seen before. It is possible to find information everywhere: social media, websites, and even in WhatsApp groups. Although its diffusion as a political tool is an old phenomenon, "fake news" differentiates by the scale, speed and reach of the information, fed by the advance of new technologies (Lobato & Marie Hurel, 2018).

In such a globalized and interconnected world, fake news gains even more strength because of its speed, spread, and power of circulation. The result is clear: immediate responses with global consequences. The challenge, therefore, is even bigger: how to control the veracity of information with this dynamic? Moreover, the current phase of globalization justifies this question, because besides acceleration, intensification, deepening, and broadening, it was the concept of information-driven content that brought online platforms and the Internet to be the main infrastructures of globalization.

How Brazilians interact with social media

Even before the first round of the presidential elections in October 2018, 44% of Brazilian voters affirmed to use WhatsApp to read political and electoral information. However, investigations have proved that the app was used to spread alarming amounts of misinformation, rumors and fake news.

A BBC World Service poll (BBC, 2017) found that internet usage has widened and since the popularization and spread of fake news in social media, 92% of Brazilians reported a concern about not being able to discern between fact and falsehood online. Even being the highest percentage of respondents in the countries surveyed, Brazil is in the list of nations with the highest proportions opposed to any kind of government regulation about the topic.

In 2018, a research published by MindMiners showed that 83% of the people confirmed using social media as a main source of information. During the presidential elections of 2018, more than 55% of the respondents answered that they were going to use social networks as a source of information, helping them with making voting decisions (Nexo, 2018).

False political information, when made public, can damage reputations and cause real-world consequences.

During the presidential elections it wasn’t different. Journalists and social scientists realized that the false information used in the politicians' campaigns were misleading voters to get more votes based on false information. According to an XP Ipespe survey conducted in October 2018, 33% of the respondents stated that Jair Bolsonaro from the Social Liberal Party (PSL) was the biggest beneficiary of fake news, while 31% believed that his opponent Fernando Haddad from the Workers' Party (PT) benefited. The other 36% did not know how to respond or said they did not believe fake news benefited any of the candidates (Mortari, 2018).

Fake News influence by voters

Figure 2: A Brazilian survey showing that Jair Bolsonaro was the most beneficiated candidate by fake news

How fake news built each candidate

It is difficult to establish to what extent these misinformation campaigns are affiliated with political parties or candidates, but their tactics are clear: they rely on a combined pyramid and network strategy in which producers create malicious content and broadcast it to regional and local activists, who then spread the messages widely to public and private groups. From there, the messages travel even further as they are forwarded to their own contacts by trusting individuals (Tardáguila, Benevenuto & Ortellado, 2018).

The total of 123 false news checks is equivalent to almost two rumors denied per day, from August 16th until October 26th 2018.

In the first 70 days of the election campaign, around the 16th of August 2018, fact-checking initiatives debunked more than 123 news items directly linked to both candidates. The data were published by the Congressional Focus Survey and show that from these 123 publications, at least 104 were used against Fernando Haddad and his political party and 19 would be harmful to Jair Bolsonaro and his allies. The total of 123 false news checks is equivalent to almost two rumors debunked per day, from August, 16th until October 26th, when the data was published (Macedo, 2018).

Reserve military officer Jair Messias Bolsonaro was elected to be president of Brazil in 2018. Affiliated to the Partido Social Liberal [Social Liberal Party] (PSL), he was a federal deputy for seven terms between 1991 and 2018, being elected through different parties throughout his career. The PSL is known for being currently liberal only in the economic sphere, while being conservative in when it comes to customs and traditions.

Fernando Haddad is a Brazilian academic, lawyer and politician, affiliated to the Partido dos Trabalhadores [Workers' Party] (PT). He was Minister of Education and mayor of the city of São Paulo. He is a professor of political science at the University of São Paulo, from which he graduated as a bachelor in law, a master in economics and a doctor in philosophy. The Workers' Party (PT) is one of the largest social-democratic movements in Latin America.

Inside Brazilian social media during elections

The most common types of fake news distributed on social media networks and chat applications, such as WhatsApp, reveal images, videos, and texts of both politicians (and frequently their parties) with subtitles and information totally out of context. Frequently these are edited and forged.

Fake news against Fernando Haddad is usually based on the idea the he is member of a Communist party and that his project is to transform the country into a communist regime. With this idea, it is possible to find an extensive number of images describing politicians as “communists” and associating them with the governments of Cuba and Venezuela, for instance. One of the most shared images was a black-and-white photo of Fidel Castro stating that he is Fernando Haddad’s idol.

Figure 3: Fernando Haddad

On the other hand, the false news spread against Jair Bolsonaro tends to distort his position on taxes and the minimum wage, often using exaggerated data. After Bolsonaro was stabbed during a campaign event in September 2018, pictures of the candidate entering a hospital smiling, suggested that he had staged the attack. A considerable number of theories were created about this. For example, it was said that he had doctored the entire situation and that members of his party itself would have helped in the staging.

bolsonaro.jpg

Figure 4: Jair Bolsonaro

Against Fernando Haddad

A tremendous amount of fake news was shared about Fernando Haddad, presidential candidate from the left wing. The news ranged from the distortion of his government program, to rumors about his character and personal life, theories that link him to communist and extremist parties, and even more gruesome news such as the “Gay Kit” or the erotic baby bottles.

Figure 5: An image in internet says that Fernando Haddad distributed penis-shaped bottles in schools

One of these messages reports that the former mayor distributed erotic baby bottles with penis-shaped nipples to children in public schools (Figure 5). According to people sharing this kind of image, Haddad's aim would be to combat homophobia and to teach kids how to be gay. The subtitle with the bottle's image says: “Look what PT [Haddad’s party] is putting in the child day care. Oh my God”. It was proved that the erotic bottles story was fake.

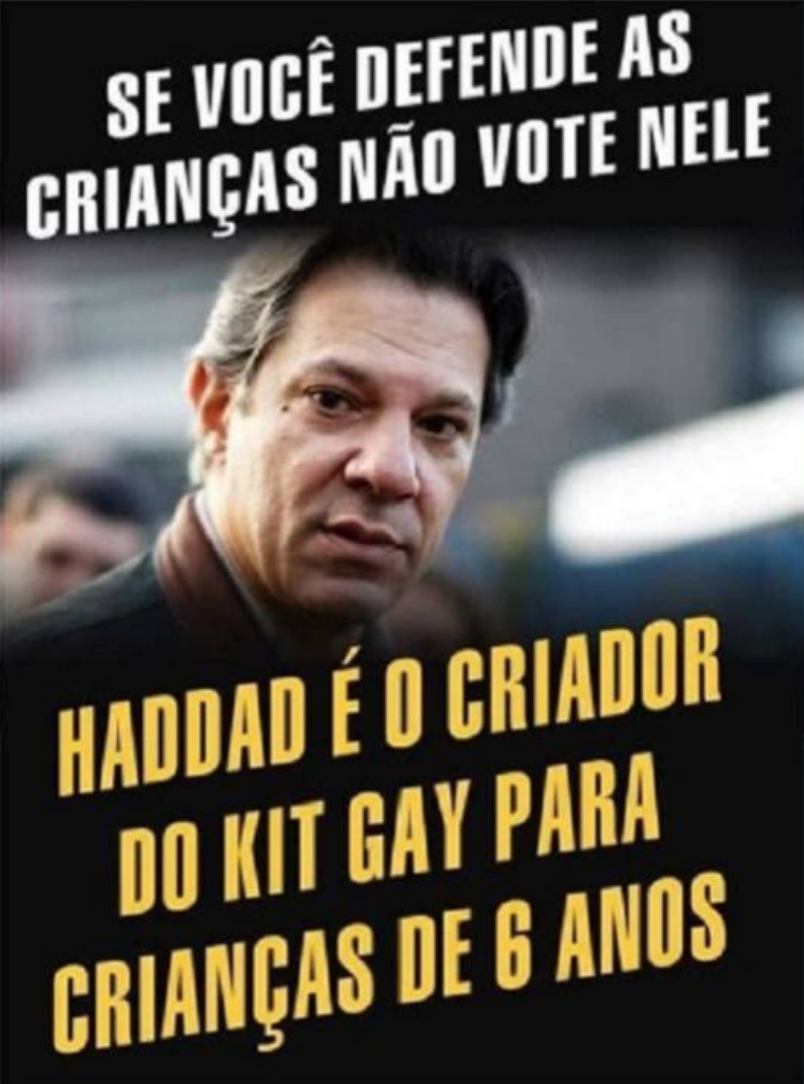

Figure 6: "If you protect children, don't vote for him".

In fact, the “Gay Kit”, as it was dubbed by Haddad’s opponents, is a project called School Without Homophobia, which the Ministry of Education, then under the management of Fernando Haddad, presented in 2011 with the support of several organizations. The goal of the project would be to provide training to teachers to deal with LGBT rights, fight against violence and prejudice, and create respect for diversity among young people and adolescents. However, the project was never implemented in schools. “If you protect children, don’t vote for him. Haddad is the creator of the Gay Kit for children of six years old”, says the text in Figure 6.

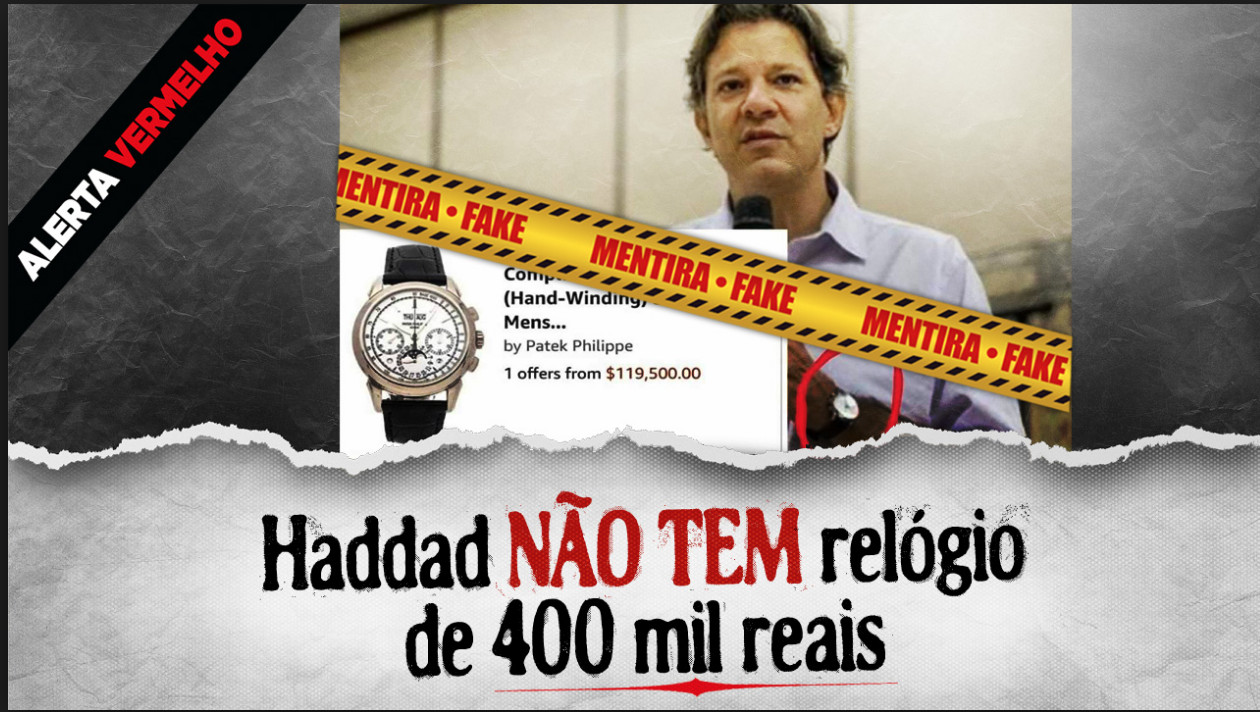

Figure 7: Haddad's party tries to deny fake news in social media

Other fake news targeted his lifestyle, such as the fake image that shows the candidate wearing a $119,500.00 wristwatch. Image 7 was made by his own party to tell people that this is a fake news and that Haddad doesn’t even have this wristwatch.

Figure 8: Image is edited in photoshop to link the government of Haddad with communist Cuba

Many more political fake images can be found. Figure 8, for example, shows men wearing olive green T-shirts and caps with Cuban soldier’s flags, indicating that the communist help from Cuba had arrived to Brazil to help with the security of Fernando Haddad. This kind of association, with the communist party, was famous during the whole electoral process, and one of the most common reasons why people said they wouldn’t vote for a communist. About the same idea, the text in figure 9 says: “Haddad plans to make a new constitution to meet communist party request”.

Figure 9: “Haddad plans to make a new constitution to meet communist party request”

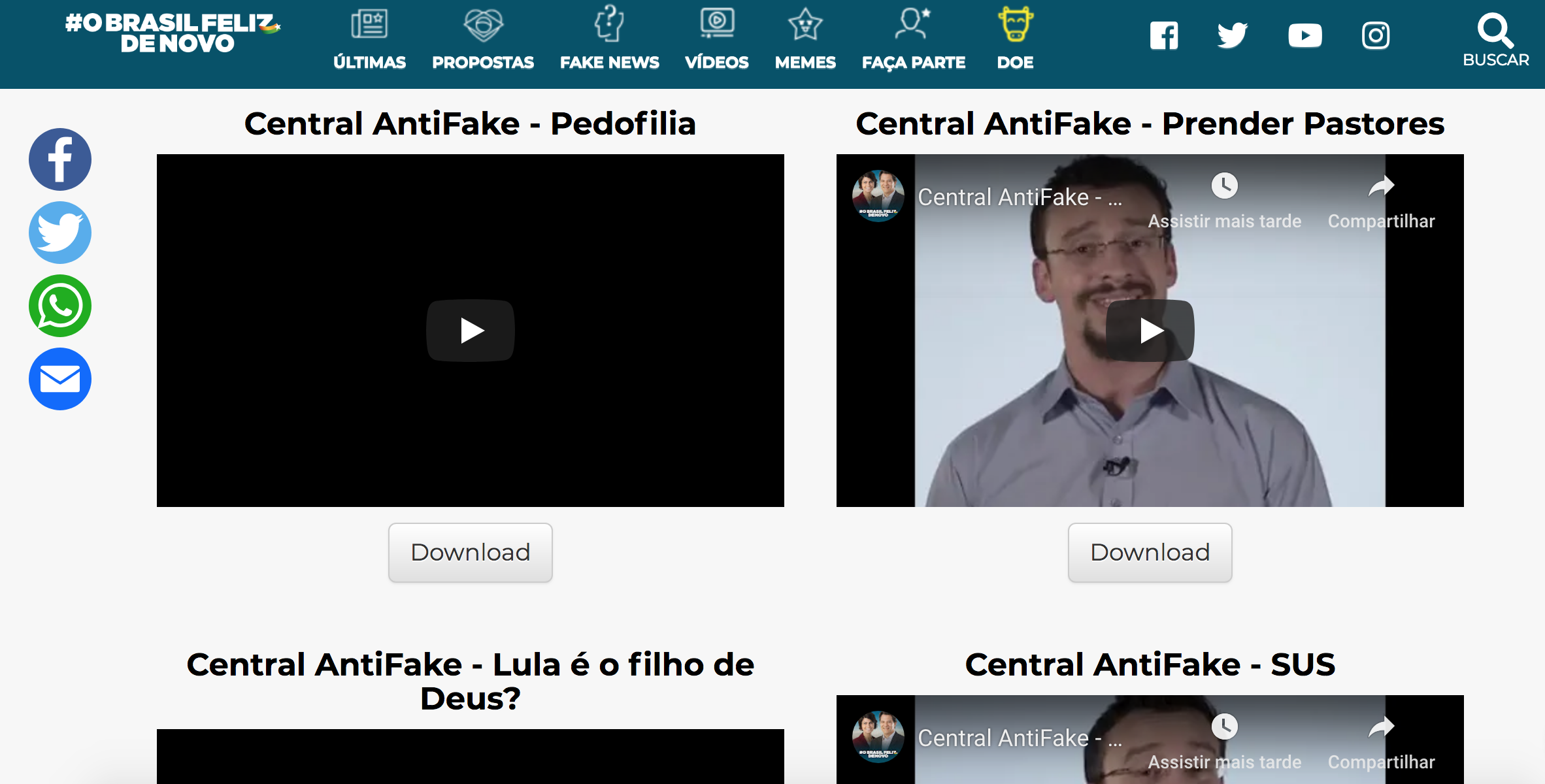

The amount of fake news distributed daily made Fernando Haddad's party create an online page (Figure 10) compiling explanatory videos about the most recurring fake news.

Figure 10: PT's website with video denying most famous fake news against the party

Against Jair Bolsonaro

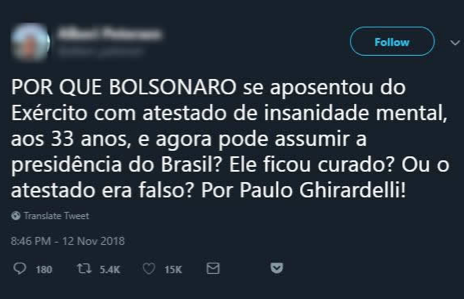

The main fake news story about Jair Bolsonaro was that he pretended being stabbed at a campaign event. However, many other false stories were scattered, trying to question his character. One example of that was the famous tweet (Figure 11) saying that he retired from the army due to mental health conditions. The text in the image says “Why Bolsonaro, retired from the army with a certificate saying that he had a mental health condition when he was 33 years old and now he can be president of Brazil? Is he healed? Was the document false? Why Paulo Ghirardelli!”. The theory was proved to be a lie. In fact, Bolsonaro was automatically transferred to the reserve in 1988 when he was elected councilman, as determined by the Military Statute.

Figure 11: Tweet about Bolsonaro tries to question his mental condition

The image in Figure 12 shows another false accusation about the candidate. The image is from a video in which Bolsonaro says that he would have liked to join Hitler in his army if he had had the chance. This video caused a huge uproar, saying that the candidate was trying to establish a Nazi party in Brazil, in the same mold of Adolf Hitler. It has been proved that the video was edited with other video cuts and distorted phrases.

Figure 12: Video posted on social media was edited to distort Bolsonaro's ideas

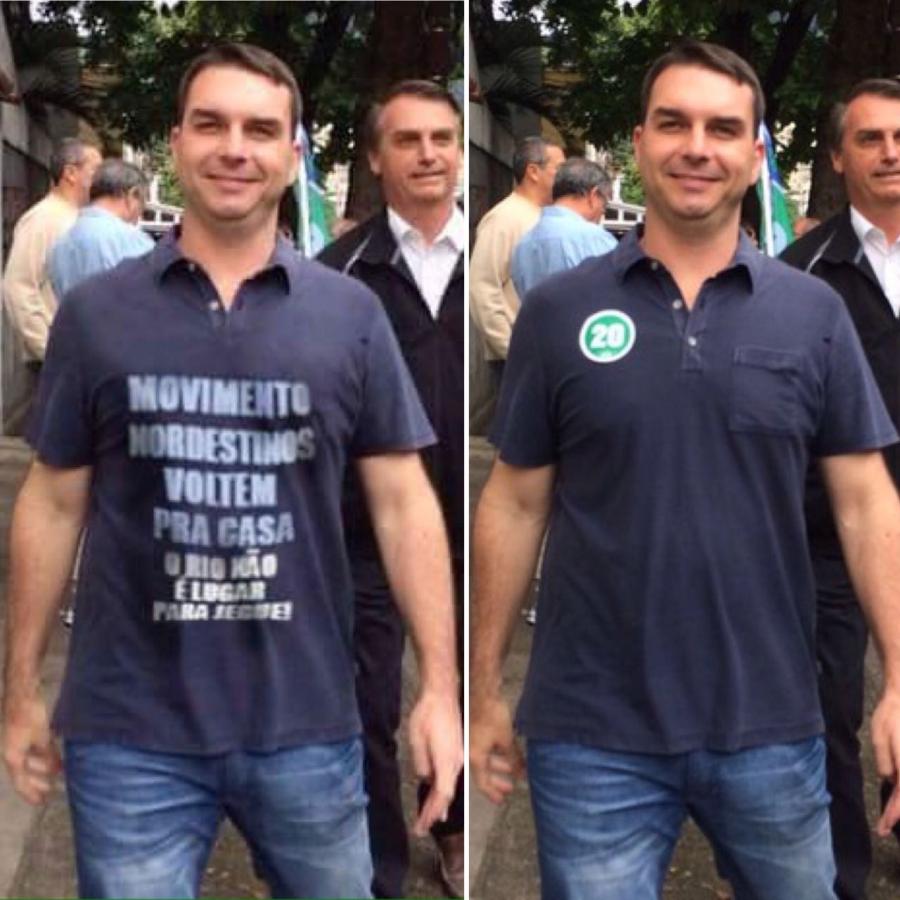

The fake news stories also involved Bolsonaro's family. Image 13 shows his son, Flávio Bolsonaro, wearing a T-shirt saying “Moviment nordestinos [people from the northeast part of Brazil] go back to your home. Rio [de Janeiro] is not the place for donkeys”. The image was widely shared on social media, even after it was proved that it was made in Photoshop. The situation opened a huge discussion in social media and even fights between people from different regions of the country.

Figure 13: On the right, the original picture, and on the left, the fake one

Fake covers of famous printed newspapers and magazines were also used to spread fake news in social media. The right cover of Figure 14 shows a fake magazine cover in which the content was modified. The original cover (on the left side of Figure 14) of Veja Magazine has the subtitle “With Bolsonaro's possible election, institutions - which have resisted the authoritarian temptations of the left party, PT - will now have to overcome the authoritarian temptations of the radical right”. In the fake cover the text says “As soon as I get to power, I'm going to do away with everything that PT did. Poor people in Brazil only serve to vote with voter's title in hand and donkey's diploma in the pocket”.

Figure 14: On the left, the fake cover, and on the right, the original one

Back to old and traditional media?

There was a significant positive development in the fight against false news in Brazil, even without any specific regulations by law against it. Many checking initiatives were started and these contributed daily to ensure safer access to news circulated on the internet. Facebook and Google have also collaborated on an initiative called Comprova, gathering 24 Brazilian newsrooms to debunk misleading links, videos, and images. However, to many academics and journalists, these efforts seem to have only a small effect when compared to the importance of the situation. The predominant means of internet access also play an important role in the type of information that reaches users and social platforms play a central role as "spaces" for debate.

Influencing public opinion and citizens during election periods is not a new practice. Before digital media and the spread of fake news on these platforms, many experts saw old media, such as newspapers, radio, magazines and television, as the villain. The process of globalization, the shortening of distances, and a highly advanced technology is also important in this context. It is also common to see old media present themselves as the alternative to the chaos of fake news. However, it is almost impossible to think, in the present day, of a world that runs away from the digital and social scene.

The alliance between business models that have advertisements as their main source of profit and aggressive practices of political propaganda, based on the demoralization of the adversary, can contribute to the propagation of the misinformation in the region (Lobato & Marie Hurel, 2018).

Fighting fake news is an important media role.

According to the paper The Fake News Machine (2017), the modern internet user is overloaded with information and it is also known that users generally have a very short attention span. In this idea, fake news is capable of grabbing people's attention and use published “facts” to conform the mindsets of their reader, making them feel like they’re part of a community and confirming their ideas. Moreover, in a political environment, this tends to be in the form of highly partisan content, turning what goes on inside Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms responsible for changing the course of whole nations.

In conclusion, exterminating fake news in today's media world is a terribly complicated and possibly utopian task. Since the rise of the network society, according to Manuel Castells (2010), globalization has been shaping new social structures. It is not a totally current phenomenon, but still, it has direct consequences in the current situation and, of course, in how a networked society deals with offline but also online flows of information.

When the facts and the backgrounds are on your side, fact checking is a devastating weapon in social media discussions.

There are no ready-made formulas or practical guides on how to solve the problem, and most likely they will never exist. However, fighting fake news is an important media role. Traditional media, coupled with fact-checking systems and new digital media tools, align and thus overcome the weakening of old traditional media gatekeepers, which has led to the disappearance of filtering barriers.

The contemporary cycle of fake news, according Blommaert (2018), is the three wheels at work between tabloids, social media, and mass media. While tabloids and social media hold the hot and hectic debates, the mass media present itself as a more passive character. This way, social media got more importance than just "echo chambers" of traditional media, becoming also responsible as critical producers of news and critical producers of the criteria for "real" and "fake" news.

Traditional media must then exploit the digital niches opened by Web 2.0 and the globalization process, and use their own tools to counter it. And to do this, there is no other way than traditional and international media to join forces and even count on the help of the people through the digital media themselves, to combat this phenomenon. In this scenario, international media publications can help readers understand a more rational point of view when placed in a national perspective.

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 31, N2.

Almeida, R., Maia, G., & Zanlorenssi, G.(2018) Como informações políticas circulam no WhatsApp. [How political informations circulates in WhatsApp]. Nexo.

Barragán, A. (2018) Cinco fake news que beneficiaram a candidatura de Bolsonaro. [Five fake news that benefited Bolsonaro’s candidature]. El País.

BBC (2017, September, 22). Fake internet content a high concern, but appetite for regulation weakens: BBC World Service Poll.

Blommaert, J. (2018). The Corbyn spy hoax and the cycle of fake news.

Benevenuto, F., Ortellado, P., & Tardáguila, C. (2018), Fake news is poisoning Brazilian politics. WhatsApp Can Stop It. The New York Times.

Cabette Fábio, A. (2017) Como notícias falsas e curtidas artificiais se tornaram um mercado mundial. [How fake news and artificial likes became a world market]. Nexo.

Castells, Manual (2010), The Rise of the Network Society. London: Blackwell.

Catraca Livre (2018). As dez piores Fake News contra Bolsonaro, Haddad, Ciro e Lula. [The ten worst fake news against Bolsonaro, Haddad, Ciro and Lula].

Gu, L., Kropotov, V., & Yarochkin, F. (2017). The fake new machine: How propagandists abuse the Internet and manipulate the public. TrendLabs.

Lobato, L., & Marie Hurel, L. (2018), Os desafios das fake news na América Latina [The challenges of fake news in Latin America].

Macedo, I. (2018), Das 123 fake news encontradas por agências de checagem, 104 beneficiaram Bolsonaro. [Of the 123 fake news found by checking agencies, 104 have benefited Bolsonaro]. Congresso em Foco UOL.

Mortari, M. (2018), Como as fake news impactaram na disputa entre Bolsonaro e Haddad, segundo eleitores. [How did the fake news hit the dispute between Bolsonaro and Haddad, according to voters]. InfoMoney.