Framing of Pride 2020 in mainstream media and on social media

The sixth month of the year is not just known as June, but also as pride month. However, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Pride 2020 was canceled worldwide. Pride month (and more generally LGBTQ+ pride) contains events related to the acceptance and visibility of LGBTQ+ people in our society. It contains celebratory elements such as pride parades but is also about a larger historical and societal context of acceptance. The month of June is specifically marked as Pride Month in the United States to commemorate the historical event of the Stonewall riots, which were demonstrations by members of the LGBTQ+ community that started at the end of June in 1969.

Pride month does not take place in the same month for each country: while many celebrations all over the world usually take place in June, other countries celebrate pride in other months or on specific days. Normally, these pride holidays contain big events such as pride parades. Due to the coronavirus, Pride in 2020 was shaped differently because these big events could not occur. These big events are often mediated, therefore the occurrence of these events is a major factor in how Pride causes draw mainstream media attention.

Because of the lack of big events to draw attention to Pride in mainstream media, coverage on Pride in 2020 is different compared to other years where events were prominent. Therefore, in this paper, I will be analyzing how big mainstream media from the Netherlands and the United States reported on pride holidays in 2020, and how they framed this coverage. This decision for countries was made on the practical reasoning of being able to understand the language, as well as to show the contrast between The Netherlands where pride events are more spread throughout multiple days and weeks in the year, and the United States where June is officially Pride Month and Pride events are concentrated in this month. From this coverage, I will analyze how this mainstream media coverage and its framing differs from a new form of journalism, namely citizen journalism. For this, I will be focussing on social media posts where users take reporting on pride themes into their own hands. Summarised, this paper will answer the question 'how is Pride 2020 framed by online news platforms from the Netherlands and the United States, and how does social media coverage differ from this?'

The aspects of this coverage and how these aspects differ between mainstream media and citizen journalism on social media will be analyzed using various concepts related to digital media and journalism. As a first, the concept of codes newsworthiness by Allan (2010) will be used. Allan (2010) also touches upon the concept of news frames, which is described in a more elaborate way by Entman (1993). When moving on to the coverage by users on social media, the features of news consumption by social media users as posed by Boczkowski, Mitchelstein & Matassi (2018) and Carlson (2016) will be used to describe how this new coverage fits into these practices.

Pride 2020 in Dutch news media

Since coverage on pride varies a lot depending on the country, both varying in quantity and framing, different countries will be analyzed separately before comparing them. The first country we will take a closer look at is the Netherlands. The Netherlands does not have June officially registered as pride month, but it does have other specific pride-related days and weeks throughout the year. One of the biggest ones in the Netherlands is Amsterdam Pride, taking place in the first week of August, with the Canal Parade as a kick-off, followed by days of pride-related activities and celebrations. Next to the parade, there are specific days such as Roze Zaterdag (Pink Saturday), which is an organized day usually at the end of June, and Paarse Vrijdag (Purple Friday) in December, on which schools show their acceptance and support by wearing purple. All these pride-related holidays have multiple dimensions to them: they are not only celebratory but also often intertwined with historical, ideological, and political meanings and values, and they focus on acceptance and safety of lgbtq+ people

Since pride is not necessarily linked to the month of June, media coverage is also more spread throughout the year, but searching for a few keywords (such as Pride, Canal Parade, Parade, etc) quickly collects coverage on these various pride days. Most of the coverage on pride seems to be at the end of July and the beginning of August, in the time period that Amsterdam Pride was supposed to take place.

Figure 1: News reports on Pride by NOS.nl: "No Canal Parade this year: 'that hurts, because that is where we show who we are'" and "[...]start alternative pride"

Since pride is a broad topic with various dimensions, the journalists have to make certain decisions on what to include or emphasize when reporting. This is what Entman (1993) defines as framing: "to select some aspects of perceived reality". This is also what happens in the Dutch media. It is immediately noticeable that there is a specific way of framing present in a lot of these articles, namely that one particular aspect of Pride is highlighted: the celebratory element. This is also an aspect of framing: frames define problems. This is exactly what happens on major Dutch media platforms such as AD.nl, NOS.nl, and Nu.nl: the cancellation of big Pride events is defined as a problem mainly because of the fact that many will be missing out on the celebratory element. Other dimensions of pride, such as the ideological goal of more acceptance, and the historical dimension of pride history are not included in this frame. Sometimes these elements are mentioned briefly within articles, but the main focus is on the cancellation of Pride events. This is episodic reporting, where the focus is on specific events, instead of thematic reporting, where the acceptance and celebration of the lgbtq+ in a larger societal and historical context would be reported.

Other dimensions of pride, such as the ideological goal of more acceptance, and the historical dimension of pride history are not included in this frame

The way in which Pride gets organized for the consumer in this specific frame ties together with what Allan (2010) describes as news values. These values help the reporter to organize and justify their selection, in which they deem certain events 'newsworthy', and deem other events not worth reporting on. Several of these news values play a role in determining whether various elements of Pride are worthy enough to be reported on. One news value that is prominent in Dutch reporting is the one of unusualness: things that happen regularly do not make it to the news, things that are out of the ordinary do. In this case, Amsterdam Pride as a big event that reoccurs every year getting canceled is unusual and therefore is newsworthy. This also ties together with other news values like timeliness, where a recent cancellation has priority over historical Pride events, and proximity, because a parade in the country is closer to the reader's world than a global context.

Pride 2020 in American news media

In contrast to the Netherlands where Pride events as well as reporting on these are more scattered throughout the year, in the United States June is established as LGBTQ Pride Month. Another difference between these countries is the fact that in the Netherlands, the biggest news platforms frame Pride 2020 in a similar way. Across online news media in the United States, this is not the case. There is for example a big contrast between the framing as done by the New York Times opposing to reporting by FOX news.

Figure 2: A few articles in the New York Times' Pride 2020 collection.

The New York times has a dedicated page where articles relating to Pride Month 2020 are collected. It is immediately visible that the framing is very different compared to the Dutch media: many of the New York times articles are thematic rather than episodic: they relate to the event of Pride Month but show a bigger context than just the events. Here, it is not just framed as celebratory, but also as historical and societal. It is framed in a way that not the cancellation of events, but rather the long history and still ongoing processes of discrimination are defined as problems. Next to this, many articles seem to have more of an educational purpose: not just to keep up with current events, but also to take into account the history that precedes these current events. By connecting this history to current events, the journalists try to increase the newsworthiness factor of relevance, because connections to present life increase the proximity to the reader's life.

Another factor of newsworthiness that is very apparent in reporting by the New York Times is the one of conflict: the reporting is not just about Pride being celebratory and happy for everyone, through many articles multiple sides of each story are reported. Through personal experiences as well as historical backgrounds, the reporting touches upon internal and external conflicts of acceptance, labeling, education, and intersectionality.

Just like the New York Times, conflict is also a prevalent visible theme within coverage surrounding Pride by FOX news, yet done in a very different way. Compared to the collection of articles on the New York Times platform, FOX news only has a few articles in 2020 that mention Pride Month or Pride 2020.

Figure 3: Headlines of two Fox News articles mentioning Pride Month in 2020.

In these articles that do mention Pride Month, it is framed not as celebratory like the Dutch reporting, not as more ideological and historical like the New York Times reporting, but rather it is framed as political. The one article describes how the Trump administration is working towards is working to decriminalize homosexuality in other countries, the other article is describing occasions on which Joe Biden spoke out against gay marriage rights. In both articles, it is visible how Pride is framed as an issue that can be weaponized to support or not support certain politicians.

Pride 2020 on social media

So far, the focus has been placed on online news in the form of articles on the publisher's website. However, this is far from the only way in which news is produced, circulated, and consumed online. Due to the rise in social media usage, the news is also increasingly consumed on these platforms, whether incidental or sought out on purpose (Boczkowski, Mitchelstien & Matassi, 2018). Not only does this mean that news publishers have to adjust to these new ways of news consumption, but it also means that mainstream media and its journalists are no longer the only gatekeepers of news, instead, the news is scattered across a multitude of platforms. This also means that sources are not fully dependent on journalists anymore, they have ways of shaping their own coverage (Carlson, 2016).

This also happened in the case of Pride 2020. Following a larger trend of online activism that sprung in 2020, social media users also shaped coverage on Pride in their own way, differing from the mainstream media coverage in framing and form. Many of these posts on Instagram utilize a specific format, namely the one of a slide show with information displayed on each of the pictures in the slide show. An example is this post by Instagram page @soyouwanttotalkabout, a page with the self-proclaimed goal of "dissecting progressive politics and social issues in graphic slideshow form". This form is also used for various posts in Pride Month, touching upon related topics such as LGBTQ+ pioneers and what it means to be an ally to the community.

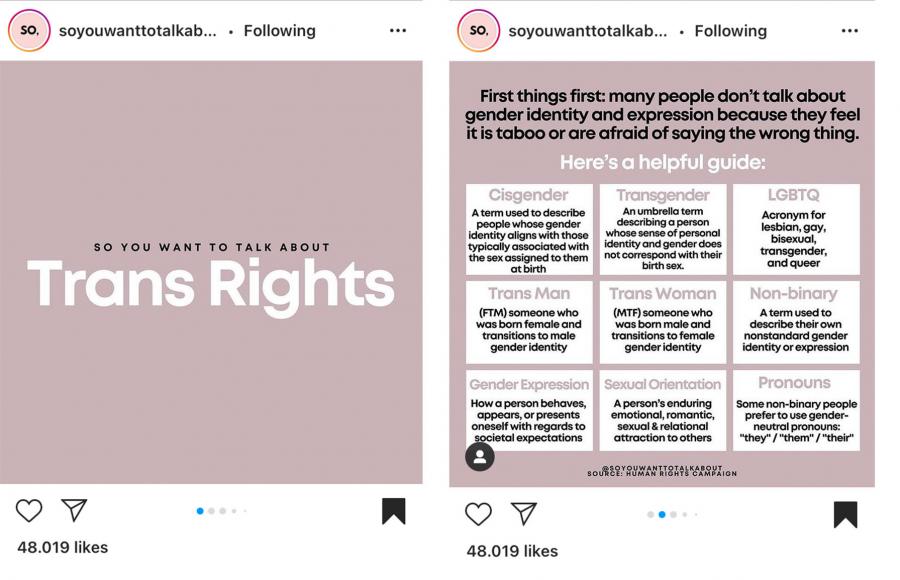

Figure 4: First two slides of a post about trans rights by @soyouwanttotalkabout.

In these posts, framing that differs from various mainstream media frames becomes visible. These posts about Pride, as well as posts about many other social issues that pages like this one discuss, are made into educational posts. In this frame, becoming more educated on various issues, their present manifestations, as well as their historical context, is suggested as (part of) a remedy. Elements like historical parts and ideological struggles are made more salient in these stories than for example the celebratory element. Pages like this show that social media users are increasingly shaping information distribution in their own way, in forms that are made to fit the platform as well as get shared around this platform easily.

Reporting on Pride 2020, a variety of frames

From the examples that were discussed in this article, it becomes apparent how the same theme of Pride in 2020 is reported on in many different ways, making use of varying frames. On some big online news platforms in the Netherlands, coverage on Pride is scattered around the year, where during Pride 2020 the main focus was on canceled events such as the canal parade in Amsterdam. Because of this focus, Pride is framed as mainly a celebratory event. In the United States, where June is officially Pride Month, the New York Times reported on pride-related themes from not just the celebratory angle but also showing the historical background as well as ideological values of acceptance and safety of lgbtq+ individuals. This is not the same for all American news media: another example of FOX news demonstrated that these journalists often frame Pride as a political issue, where it can be weaponized in political conflicts.

In a year where there were barely any offline Pride celebrations to draw attention to, there was more dependency on media to still share the goals and values of Pride. Instead of being completely dependent on mainstream media, social media users such as popular informational pages also took coverage into their own hands. These slide shows on for example Instagram focus more on the educational aspect, both about present society and historical context. All these different reports on Pride Month 2020 show that the same reality is made into different realities through framing.

References

Allan, S. (2010). News culture. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Boczkowski, P. J., Mitchelstein, E., & Matassi, M. (2018). “News comes across when I’m in a moment of leisure”: Understanding the practices of incidental news consumption on social media. New media & society, 20 (10), 3523-3539.

Carlson, M. (2016). Sources as news producers. The SAGE handbook of digital journalism, 236-249.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of communication, 43 (4), 51-58.