Instagram slideshows: making the political 'aesthetic'

With Instagram reaching its 10th year in 2020, the way we utilise and communicate on the platform is bound to evolve. The early days of white borders and not-so-subtle filters are long gone - instead we now have pastel-toned, ‘aesthetic’ graphic slideshows. Although Instagram remains a visual content sharing platform for selfies, sunsets, and video content, the murder of George Floyd in 2020 brought about changes on the platform.

The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in 2020 resulted in an abundance of black squares, BLM-related influencer content, and, most prominently, a surge in 'aesthetic' Instagram slideshows. In this article, we will explore some of the many dimensions of these slideshows and how the hybrid media system allowed these slideshows to influence the BLM movement.

The rise of the aesthetic slideshow

In the weeks following George Floyd’s murder, aesthetic Instagram slideshows took over Instagram as quickly as people took to the streets in protest. These slideshows are graphic sets of PowerPoint-like presentations posted on Instagram, with mostly pastel colours and educational content about world events. With their minimal text and carefully chosen designs, these slideshows serve as ‘guides’ for people who want to get the gist of a particular topic, and their layout enables easy sharing on social media.

These slideshows serve as ‘guides’ for people who want to get the gist of a particular topic

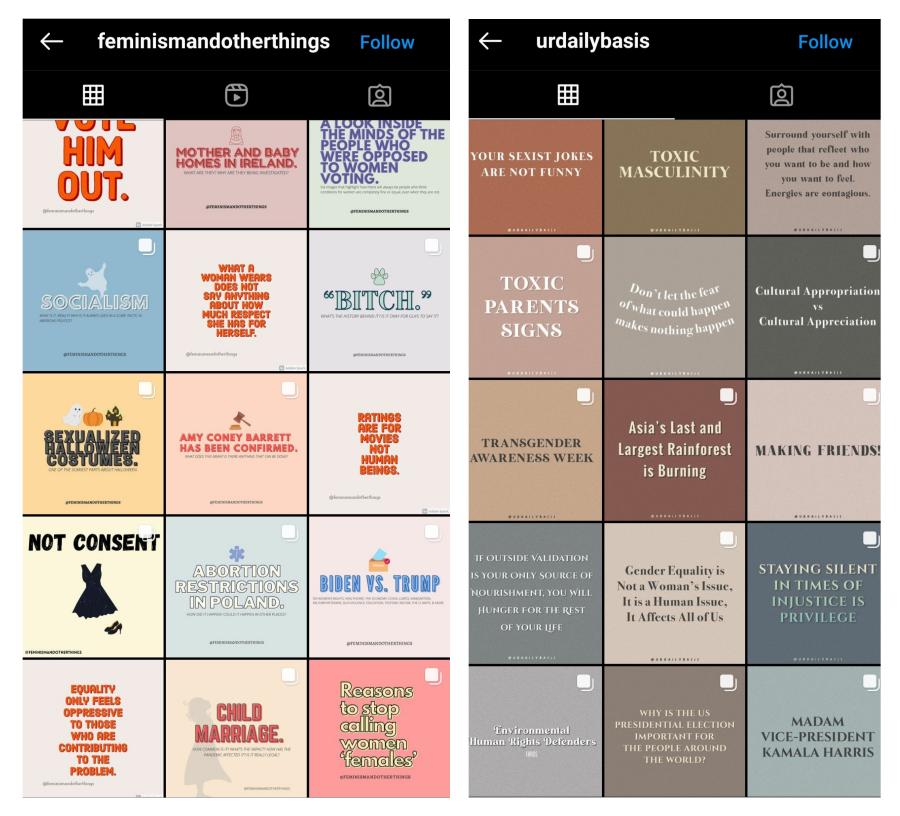

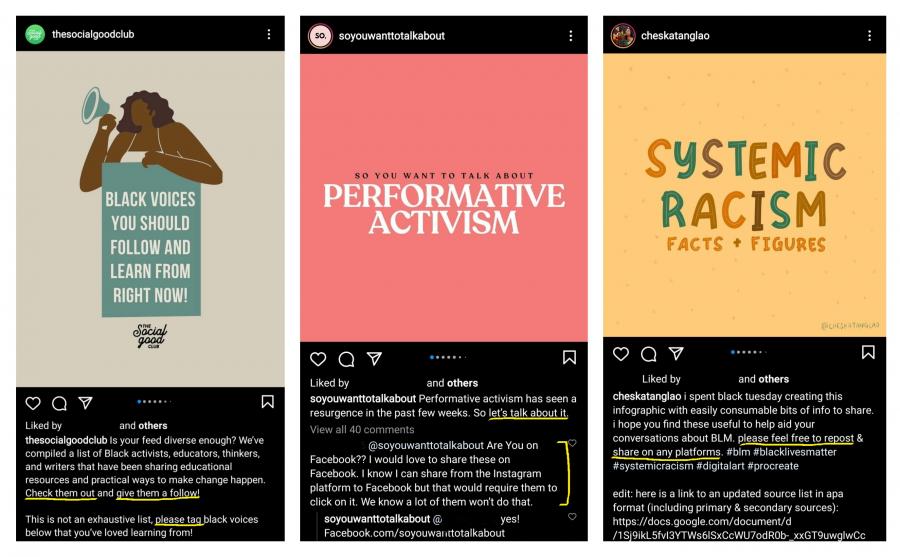

Slideshow topics typically center on general current events- not just the BLM movement (Figure 1). Various Instagram pages focus on different topics, such as feminism, news stories in a specific country, or environmental issues. Although these ‘guides’ discuss serious and complex topics, they are unable to explain every detail of the issues due to the limited space; they can only provide basic and general knowledge.

Figure 1: Different types of aesthetic Instagram slideshows

People still turn to these guides as a way to quickly educate themselves on a certain topic rather than reading books, watching documentaries, or listening to lectures. As people get busier and multitask more, the nature of news uptake has changed: people prefer easily accessible information that only requires a few miutes to digest and share. In other words, Instagram slideshows are perfect bite-sized pieces of news.

The hybrid media system

The media landscape has changed over the years: digital media now interacts with traditional media to form the hybrid media system. The hybrid media system is a concept formulated by Andrew Chadwick in which the distinction between old and new media has dissolved to form an interconnected media system that allows new actors to come into play (Chadwick et al., 2016).

News on the BLM movement is shared on traditional news media, but online media platforms also play a significant role in the attention it receives. Large quantities of information are constantly circulated in the media system, and news is readily available on many different platforms. This motivates dual screening or “the complex bundle of practices that involve integrating, and switching across and between, live broadcast media and social media” (Vaccari et al., 2015).

Dual screening in relation to the BLM movement mostly occurs when significant events, such as protests, occur, and people feel obligated to voice their opinions. People usually turn to their social media accounts to show what they are doing, ask questions, and engage in interactions with their acquaintances (Morris & Panovich, 2010).

Instagram slideshows are perfect bite-sized pieces of news.

Engaging in dual screening provides a way for people to stay informed and more importantly, have a voice. Passive dual screening can take the form of searching for topics, reading posts, or following a hashtag. Active dual screening emphasises the role of civilians in influencing others: posting or Tweeting, tagging people, using hashtags and private messaging are just some of the many ways people can influence not only other civilians but also the media and politicians.

A study done by Wohn and Na (2011) found that when people want to be acknowledged as part of a group, they engage in dual screening and utilise modes such as hashtags as a sign of cohesivity. People express “attention, emotion, information and opinion” (Wohn & Na, 2011) in their tweets and hope to feel solidarity with others doing the same.

In part because of online organizing, including dual screening, BLM has become a political issue. It was an influential factor in the 2020 U.S. elections, has pushed for police defunding policies, and has provoked politicians to take a clear stance on police brutality. Through hashtag virality and social media circulation, BLM grew from localized protests to an international movement.

What you do online matters

In an age where online content creation is made easy for users, we can do just about anything online. We can even participate in events despite being far away from the event's location. A large portion of Internet users are aware of the BLM protests, but many are also not from the United States. Although the BLM movement is focused on the United States, many activists from different parts of the world joined in to create informative content. People with the skills to do so edited videos, wrote messages, and created aesthetic Instagram slideshows.

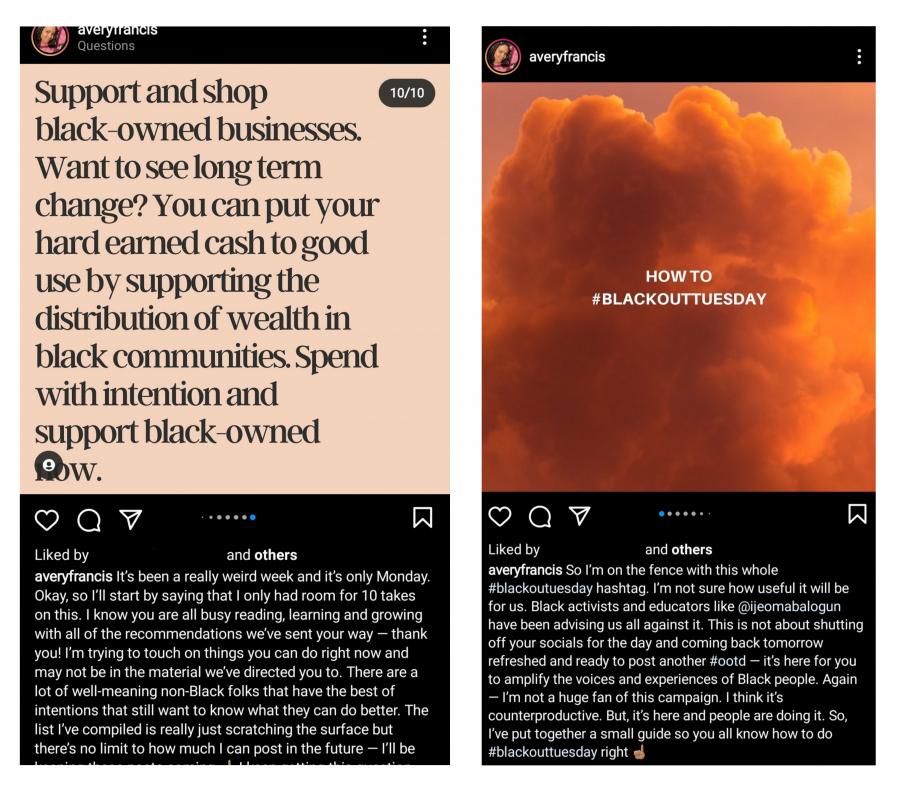

Slideshows about the BLM movement did not stop at informing people about George Floyd: they showcased everything from small Black-owned businesses to educational resources and different organisations to support.

Figure 2: Slideshows on @averyfrancis’ account related to the BLM movement about Black-owned shops (left) and how to participate in #blackouttuesday properly

According to Chadwick et al. (2016), “digital media are both forms of communication and organization” and creating and reacting to a specific issue in a timely manner is the “key to exercising power.” Many Instagram accounts, although once personal accounts, quickly gained thousands of followers through these slideshows. Whether becoming an influencer was intentional or not, one thing is for sure: these accounts started to gain followers as the BLM movement gained ground in public discourse.

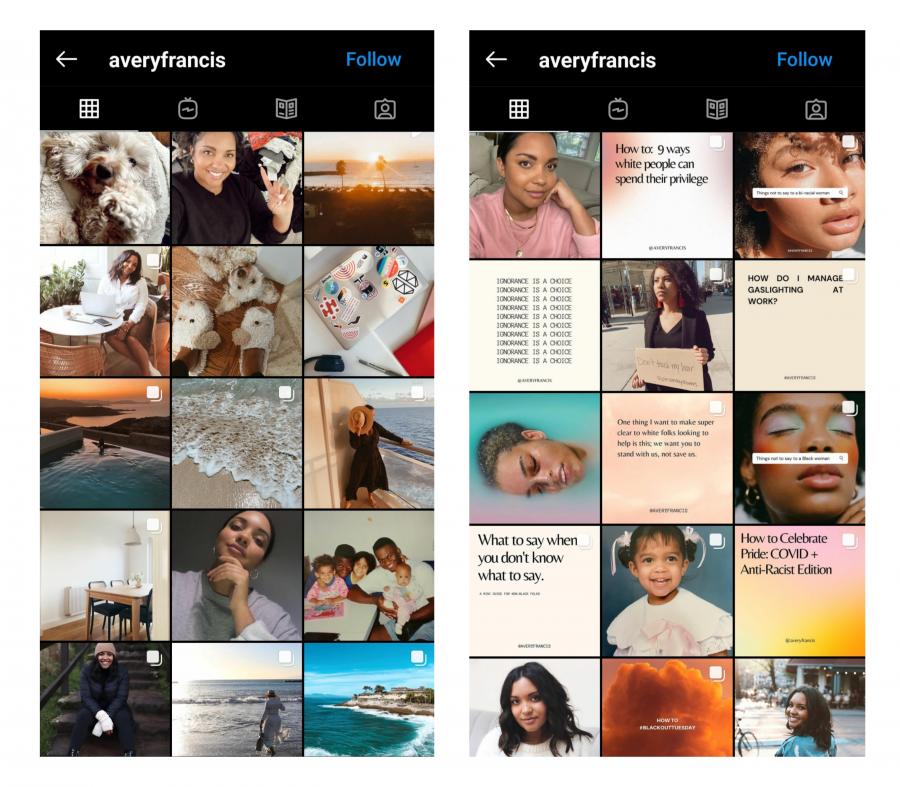

Figure 3: Avery Francis' Instagram feed before (left) and during (right) the height of the BLM movement

Avery Francis runs one of the accounts that generated a following during the height of the 2020 BLM protests, and we can distinguish a difference in the type of content she posts before and after gaining followers. Figure 3 (above) shows that Francis previously posted photos relating to her personal life (family, pets, holidays) but recently has changed to a mixture of personal photos and activist content.

Because she is aware of her increased following, Francis has utilised this attention to share informative slideshows about racism. Attention stemming from the BLM movement made way for Francis to become a new actor in online activism circles. By creating content in a timely manner she was able to communicate information to her followers about an issue she finds important.

Moreover, gaining an audience allowed Francis to combine activism and commercial purposes, acquiring paid promotions to spread awareness on topics like body positivity. Francis is one example of the hybrid media system providing opportunities for non-elites to gain influence.

Algorithmic activism

In addition to people protesting on the streets, Internet users can play the role of activist online. Online activism can also be called hybrid activism, referring to the mixture of social media and offline activism and the use of platforms' algorithms to increase visibility both online and offline.

Hybrid activism utilises social media to amplify movements' and activists' voices. There are many ways in which people can contribute to movements online and having collective knowledge about current events can lead to the formation of group identity. By mixing online media and traditional media, social issues are amplified and movements can have a bigger impact.

Hybrid media logics emphasize how norms “that determine the character of mediation evolve across and between different media” (Chadwick et al., 2016). Actors in the hybrid media system can decide what combination of media platforms is most appropriate for the creation of political awareness. Digital media provides an 'aura of authenticity' and a sense of familiarity to audiences, as many social media users not only consume but also produce content.

Online petitions, crowdfunding, and mainstream media advertisements allow people from all over the world to learn and work together to create change. Activists, citizens, algorithms, and even bots interact with each other through social media affordances to form new discourses. In this sense, digital media plays a role bigger than just being an intermediary: “it shapes the performance of social acts instead of merely facilitating them” (van Dijck, 2013). When activists produce content such as aesthetic slideshows, it is not just about content. Visible metrics in the form of likes, shares, and comments demonstrate the significance of a movement.

In the digital age, people measure a content’s credibility with visible metrics, where a popular post is relevant because of its high visibility, not because of its content or creator. This form of activism is recognised as ‘algorithmic activism’, and it “contributes to spreading the message of a politician or movement, by interacting with the post in order to trigger the algorithms of the medium, so that it boosts the popularity rankings of this message and its messenger."

Algorithmic activism requires activists to not only have a steady and firm stand for their supported cause or movement but to also have comprehensive knowledge of how a platform’s algorithm operates. Influencers like Avery Francis partake in digital media’s "economy of virality" (Venturini, 2019) and attempt to capture users' attention by using different features of social media platforms. This way “audience labour” (Fisher, 2015) in the form of interaction with posts can be performed. By algorithmically garnering attention to her posts, Francis' role as an influencer (both paid and unpaid) contributes to the BLM movement.

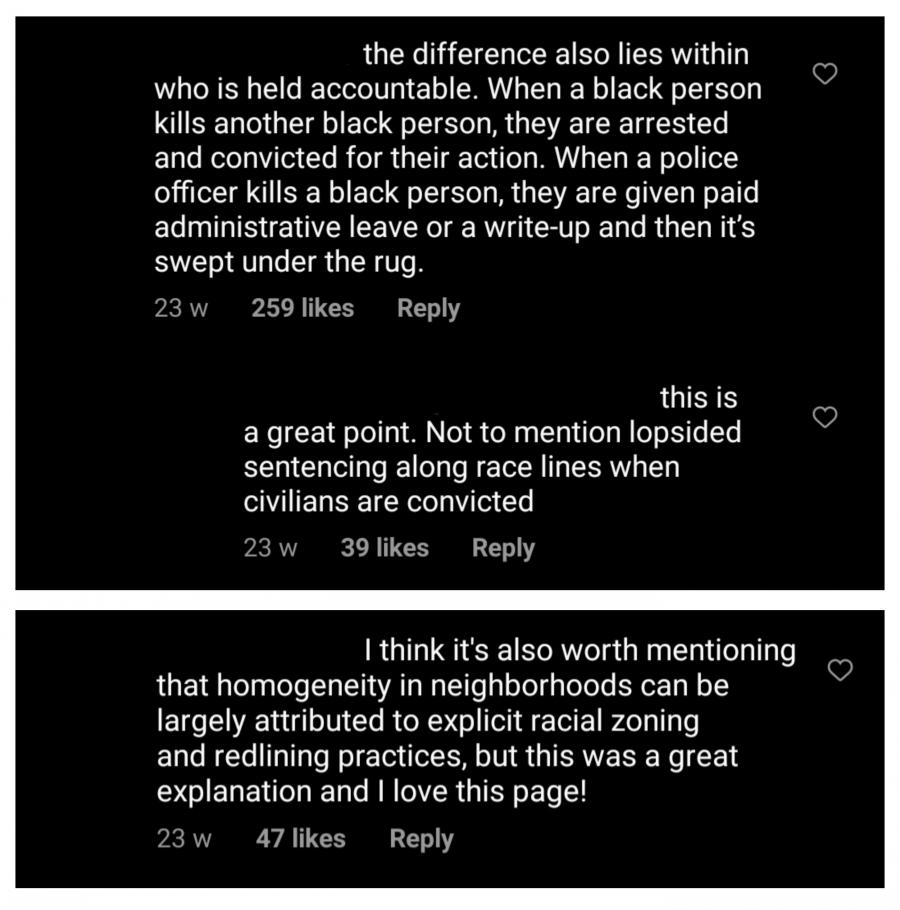

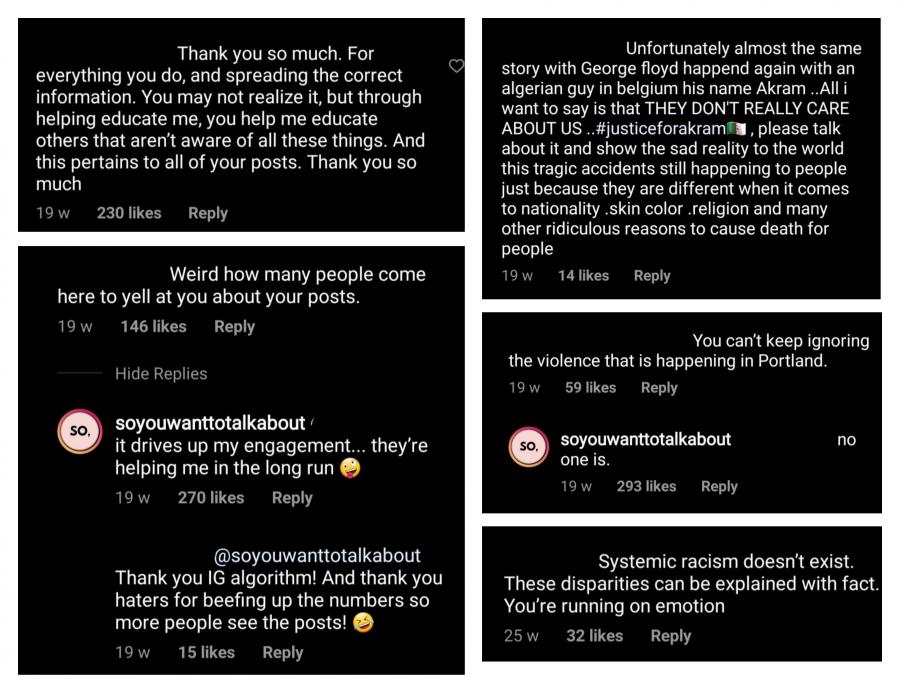

With Instagram slideshows, the audience is encouraged to share posts and ask questions in the comments section. This stimulates interaction between users and encourages learning, both from the content posted and writing and reading comments. Figure 4, below, shows a comment and responses with additional information coming from the audience themselves. By commenting, people have the freedom to express their beliefs and add information they consider important.

Figure 4: Instagram users commenting their opinions relating to the content posted

Figure 5: Positive comments and criticism under @soyouwanttotalkabout posts

As seen above, there are positive and negative comments about the posted slideshow. Some commenters want other issues to be highlighted but many also appreciating the slideshow. The owner of @soyouwanttotalkabout seems to understand the way Instagram algorithm works - by stating "it drives up my engagement", the account demonstrates that algorithmic activists have a good understanding of the platform's algorithm.

Taking aesthetics offline

Digital media can have significant impact on activism. Apart from sharing information, social media affordances also allow for the mass coordination of offline protests. Gerbaudo has termed this use of social media to organise offline protests ‘choreography of assembly’. Activists use social media, he argues, and this shapes 'the way in which people come together and act together” (Gerbaudo, 2012). Protests choreographed using online affordances normally utilise emotional ‘scene-setting’ and scripts the way people act while protesting.

Although slideshows are not guaranteed to be able to choreograph large masses of people offline, they do discuss offline protesting in their posts, so audiences are regularly exposed to the topic. The more frequently a topic is discussed, the more people tend to remember and pay attention to it. This may in turn motivate people to go out and join protests.

Many slideshows provide information about offline protests, such as ways to protest safely during COVID-19. Some activists also create content that advises people on what to (not) say and do. Furthermore, Gerbaudo (2012) notes that within choreography of assembly, online activists seem to to choreograph the way people should act. Instead of having information originate from any central leaadership, information flows from a network of activists.

In this way, we can identify a form of 'soft' leadership, whereby activists spend their time designing slideshows and compiling content while also encouraging others to “share” and “comment.” They are de facto leaders without taking leadership responsibilities. Not only are regular citizens sharing content from online activists, celebrities and influencers also share posts so that information can reach more people. Everyone can have a voice and share their opinions with their connections.

Figure 6: Different ways of stimulating audience engagement ("please tag", "give them a follow", "feel free to repost and share")

Maly (2020) notes that messages in the hybrid media system are produced to get attention: shares, comments, and views are only some of the things that matter. Activists tend to create posts that invoke emotions. Content with an emotional nature usually gains more visibility, provoking interactions and pushing the algorithm's proverbial buttons, making emotional content viral. Moreover, influencers must keep up with trends in order to continue stimulating audience interaction. Pastel colours and minimalistic typography just happened to be the trend, and activists used this opportunity to attract interest.

The aesthetic appeal of these slideshows is used to catch Instagram users' eye - mostly because people tend to be charmed by visually attractive content. Jess from @soyouwanttotalkabout expressed how she initially used bright colours and bubbly fonts but then modified them to have pastel tones. She aims to especially appeal to “corporate-minded, girl-boss feminists” and “apolitical people”, similar to the business strategies of contemporary brands. The aesthetic nature of these slideshows is in favour of both the activist and their audiences, as a neat and trendy feed is preferred by their target audience.

Is ‘sharing’ really activism?

Within social media, people can decide how active they want to be in advocating for a particular movement or a cause. Slacktivism ( a mixture of slacker and activism) is a “term to describe feel-good online activism that has zero political or social impact.” It is mostly done through social media and completed with minimum effort.

Movements such as Black Lives Matter welcome people everywhere to support their cause. On social media, liking, sharing and commenting under Instagram slideshows is effortless and takes a short amount of time. By sharing, users are sharing information to their acquaintances, allowing information to circulate to more people, creating awareness. This may lead to people actually showing interest in the movement and if enough people are talking about an issue, other people may start paying attention to it. These interested people will share a common identity and may actually take action in real life.

Many activists encourage their audience to do follow-up research such as watching documentaries and reading books, or even donating to organisations. They also come up with different ways in which people can contribute to the BLM movement while still being safe at home by collaborating with other actors, for example, YouTubers. Many YouTubers posted videos during the height of the 2020 BLM protests and donated the amount they earned on that video to a BLM-related organisation.

Instagram slideshows should not be the end of a person’s activism.

In the descriptions of many BLM-related videos, Youtubers will mention the foundations the revenue will go towards, followed with links to petitions, donations, and educational resources. We can see that from a passive form of activism (watching videos), people are directed to commit themselves further and contribute to the BLM movement. This does not just happen on YouTube: People utilise the ‘swipe up’ feature on Instagram stories and include links to resources on their Instagram bios. However these actions require more time and dedication, something social media culture is not built upon.

The new start of Instagram slideshows

Instagram slideshows are a lot more than just its aesthetically pleasing and feed-perfect designs - they can be heavily political and function as one element in the choreographing of group identities and offline protests. We have used the BLM movement to analyse the effectiveness of these slideshows and discussed their positive and negative aspects.

The prominence of the hybrid media system has enabled people to use new methods of activism to initiate changes within a movement. This shows just how much power new media possesses.

Trends come and go rapidly in social media. What is relevant today may be considered old-fashioned tomorrow. The same can be said about movements reliant on social media. To make a movement work to its full potential, we need to act further than just screen tapping. Instagram slideshows should not be the end of a person’s activism.

References

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J.W. & Smith, A. P. (2016). Politics in the age of hybrid media: power, systems, and media logics. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbø, A. Olof Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics (pp. 7-22). Routledge.

Fisher, E. (2015). Class struggles in the digital frontier: Audience labour theory and social media users. Information, Communication & Society, 18(9), 1108-1122.

Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism. Pluto Press.

Maly, I. (2020). Algorithmic Populism and the Datafication and Gamification of the People by Flemish Interest in Belgium. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 59(1).

Morris, M., Teevan, J., & Panovich, K. (2010). What do people ask their social networks, and why?: A survey study of status message q&a behavior. CHI.

Vaccari, C., Chadwick, A. & O'Loughlin, B. (2015). Dual Screening the Political: Media Events, Social Media, and Citizen Engagement. Journal of Communication, 65(5), 1041-1061.

van Dijck, J. (2013). The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford University Press.

Venturini, T. (2019). From fake to junk news: The data politics of online virality. In D. Bigo, E. Isin, and E. Ruppert (Eds.), Data politics: Worlds, subjects, rights. Routledge.

Wohn, D. Y., & Na, E.-K. (2011). Tweeting about TV: Sharing television viewing experiences via social media message streams. First Monday, 16(3).