Music festivals: Interconnectedness all over the world

After the famous Woodstock festival in 1969, music festivals gradually changed from local into more global events. They also became commodified thanks to the Internet, social media and the cheap flights offered by budget airlines. Anyone can attend festivals anywhere in the world provided they have the resources (and that it is safe). For example, Tomorrowland in Belgium hosts attendees from all over the world every year.

But with everything we know now about sustainability, we are seeing a trend of "glocalisation" (Connel & Gibson, 2003). Within this new trend music tourism movements have emerged, showing the interconnectedness of local people on a global scale via online and offline communities.

Intensifying this glocalisation might be to everyone's advantage because it fits the green ambition of big global music festivals nowadays, in which more local music festival characteristics have been adopted.

Woodstock

The global view of music festivals started with Woodstock, the origin of all international music festivals. Woodstock Music and Art Fair, the legendary festival that all other big music festivals since are still being compared to, can be characterized with the following catchwords (Rudolph, 2016):

- Bethel, New York, 600-acre farm

- 31 bands

- 4 days long, 24/7 music playing

- 14th August – 18th August 1969

- 400,000 – 500,000 attendees

- Public nudity and drug-use

- Love for the music

- Freedom of expression

- Promoted through TV and radio channels

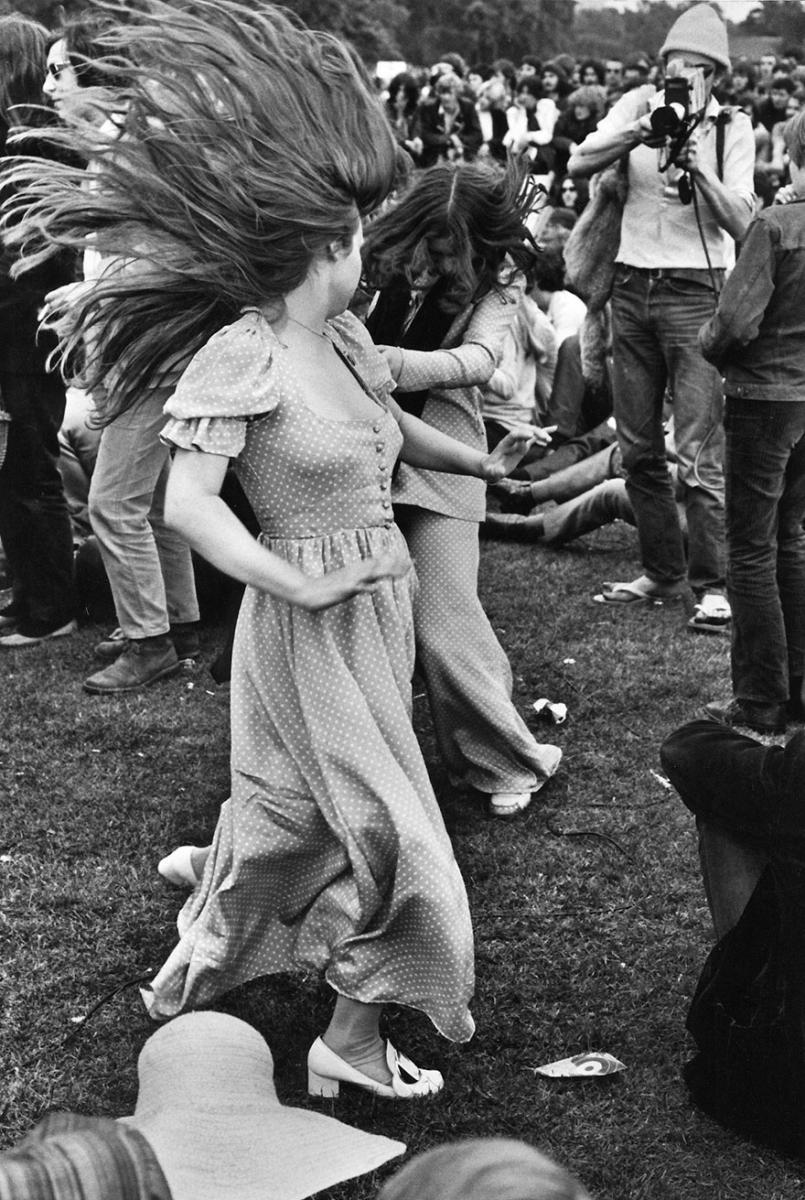

Women dancing at Woodstock Festival in 1969

From here on, music festivals became more and more focused on commerce and entertainment. People from all over the world come together to enjoy international music festivals: the variety of artists, the over-priced food, and the sun. Music festivals and the number of attendees per festival are increasing every year (Rudolph, 2016). Dating back as far as the middle ages, music festivals have now become phenomena for the masses, and no longer only for the higher-class elites (Laschua & Long, 2014).

Music tourism movements

In this age of globalization, music tourism is a very fast-growing industry. Tourists travel to the other side of the world to attend. From 1995 onwards, music festivals started being seen as historical phenomena that expressed a certain sense of community, i.e. that one belonged to a certain group (Giorgi, Sassatelli, & Delanty, 2011).

This fast-growing music industry is essentially a cultural form of the current phase of globalization as we now see globalization as the process in which flows of people and networks move to different parts of the world.

But this new cultural aspect actually indicates the expression of the culture that has emerged within the different communities that have been shaped because of globalization, or "cultural globalization" (Giorgi et al., 2011). And this sense of different cultures coming together indicate a certain feeling of internationalism.

This fast-growing music industry is essentially a cultural form of the current phase of globalization.

The process also underlies the way in which music is now approachable for everyone. In the contemporary world, we witness the emergence of certain "global mediascapes" (Appadurai, 1990). And these global mediascapes have emerged because of big media corporations using niche markets as hubs to form new musical sounds that are to be distributed to different places all over the world. This process has caused the music of music festivals to go global becoming international events (Connel & Gibson, 2003).

Local niche festivals vs global festivals

The fact that online and offline communities and thus global and local festivals can exist alongside each other but also interfere with each other has to do with the emergence of the Internet in the mid 1990's. A great example is the global music festival Tomorrowland. The Internet is being used in various ways by music festival organizers: on the one hand, to sell tickets to customers online, and on the other, to give fans the opportunity to voice their enthusiasm on the Internet (Bennet & Reterson, 2004).

What makes local music festivals different from the big and global music festivals is the fact that the local ones distinguish themselves by having created a particular local scene with typical musical signs (Bennet et al., 2004). What is so special about global music festivals when it comes to their interference with local music festivals, is that the global festivals now connect different local scenes forging them into "a trans local scene" (Bennet et al., 2004).

Nowadays, the special combination of local and global music festivals where the domestic has tapped into the international aspect, can be clearly seen in global events. These festivals show the symbolic co-existence of non-music elements they inherited originally from local music festivals with their own global scale. These are the type of characteristics that you as a person can really learn something from. For example, raising more awareness about sustainability and a low-carbon society (Giorgi et al., 2001). These aspects really attract the young audiences of today, who are hyper-aware of needing to take care of nature (Rudolph, 2016).

Global music festivals nowadays should offer something extra next to being an immersive experience, a kind of paradise, an imagined world that you step into (Kruger & Trandafoiu, 2014). For instance, big Australian Festivals show "the greenism of festivals", in which they indicate that recycling is very important for our societies (Giorgi et al., 2001).

Other festivals with such local and authentic characteristics, for instance, include literature festivals, art festivals and African film festivals. The local ones have created a voice to which the global ones listen (Gibson & Connel, 2003).

Big Australian Festivals show "the greenism of festivals", in which they indicate that recycling is very important for our societies.

Local Holy Art festival in India

The commodification of music festivals

Because of globalization, worldwide music festivals have become commodified and commercialized, they are being sold as a kind of product for the consumers, the people that attend these festivals. As a result, a whole new sort of economy has emerged based only on the earnings from cultural tourism: of big and global music festivals (Bennet & Peterson, 2004).

For example, Byron Bay, which hosts big music festivals, has changed rapidly because of this form of economy. Flows of commodities have emerged, such as the consumption of tickets for special events. This kind of events have attracted many tourists (Gibson & Connel, 2003).

Global Music Festival, Byron Bay (Australia)

In the 1970's, the commercialization of music went so far that the term "commercial music" (Holt & Antti-Ville, 2017) was introduced, indicating in art that a music festival is a kind of product that you can buy.

The place where a music festival takes place is also an important factor in the commodification process. The location should have a certain meaning of authenticity and cultivate a sense of "memory and nostalgia" (Laschua & Long, 2014) which attracts the investments of consumers.

Effects of massive exposure via the Internet

Social media play a very special role in the interconnectedness of different parts of the world (Becker & Gravano, 2009). Via different social media platforms, the big corporations behind global music festivals can share their message with everyone around the world who likes to attend these festivals and are potential customers.

For instance, the big corporations organizing global music festivals, can easily share their artist line-up, a sneak-peak of the camping site where the different communities of people will come together, and the "after movie". This increases fans' excitement as they start counting down the days till the music festival starts. This also leads to tickets sometimes being sold out in two seconds (Kazakulova & Kuhn, 2012). Social media can also be of great value to the more local niche music festivals. These platforms are a great and valuable source of information on the event for the attendees (Kazakulova & Kuhn, 2012).

Music tourism has increased rapidly because of the arrival of budget airlines and cheap flights too. In the 1990’s, airlines such as Ryanair and EasyJet were launched and they were used as a transport line for attendees of these big worldwide music festivals. These budget airlines sponsor such big music events; in fact, "the sponsorship budgets have never been higher" (Laing, 2009), and social media play a very important role in this, because it is via these platforms that budget airlines show the possibilities and prices for this kind of transport to a big music festival.

Social media have also led to the fact that countries have regained their self-confidence when it comes to musical talents. They present musicians from their country to the rest of the world, via the Internet and later via global music festivals, because everyone and everything can be watched and discovered online. Most global music festivals can be found in Europe, but they really dominate the rest of the world (Laing, 2009).

The main purpose of these global music festivals at the end of the day is to earn a lot of money, while also cultivating an increased sense of environmental consciousness and a nostalgia feeling, which the young audience identifies with (Laing, 2009).

These budget airlines sponsor such big music festivals; in fact, "the sponsorship budgets have never been higher".

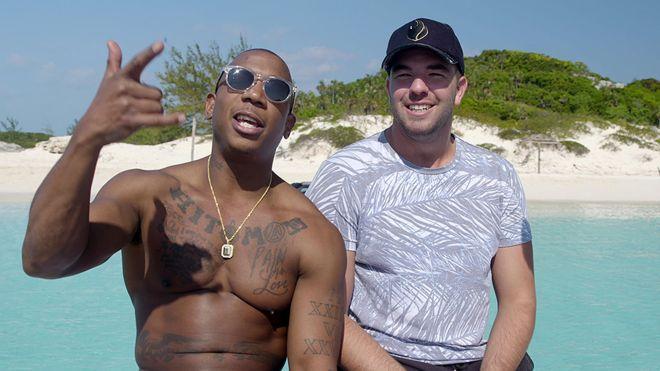

The use of social media for big global music festivals can unfortunately also lead to negative outcomes as organizers can create a fake world that everybody longs for. An example is Fyre Festival, a festival that actually never took place in the end. In 2016, entrepreneur Billy McFarland and American rapper Ja Rule developed an app which made it possible to book multiple artists for different music events. The two gentlemen came up with the idea of using the new app so that they could start selling tickets for a very luxurious music festival lasting two weeks on a remote island in the Bahamas (Moline, 2019).

Fyre Festival founders Ja Rule & Billy McFarland

Fyre Festival, a festival that actually never took place.

The team started selling tickets for Fyre Festival for around $25,000 per person. Included in the ticket were personal chefs, private yachts, and more luxurious activities. They made a promotional movie and shared it via social media with the whole world. Billy McFarland and Ja Rule made it seem as if this was the most amazing music festival you could ever experience.

Via their social network, they managed to have famous models and celebrities join the creation of the promotional video. They managed to get Kendall Jenner, Bella Hadid and Hailey Baldwin to fly in for a big amount of money. The price being paid was close to $250,000 per person. After the promotional movie was made, the famous models and celebrities had to post the video on their news feed on all their social media accounts, with the caption #FyreFestival (Moline, 2019).

The Fyre Festival reality

Eventually, Billy McFarland made all the wrong choices: thousands of people arrived on the island and nothing had been arranged. There were not enough tents and beds for everyone, not enough food and water, the stages were not installed yet and no artists were booked. This fiasco eventually lead to Billy McFarland "facing a restitution of $26 million in total and a serving of 6 years in prison" (Moline, 2019). As this example shows, social media can be a tool for easy mass manipulation.

Conclusion

Music festivals are very popular in the Netherlands and Belgium and many young people really make an effort to attend one or more of them each year. When I look at these festivals, I can see a lot of the changes happening that I mentioned earlier. The music festivals are becoming bigger and bigger and change into more of a commodity, where nothing is ever enough. But the organisers of music festivals must not forget that their focus needs to be on greenism more than ever. If not, they will start to lose their young audience. Their focus needs to be on the future and the environment. Cheap flights are not a positive part of that.

So, the mix between local niche and global music festivals needs to be increased, so that more characteristics of local music festivals can be adopted in the global music festivals.

Still, the global music festivals will always be popular. People will still go to these festivals to enjoy themselves and feel a sense of community. Social media will be used more and more for this purpose, such as in the case of Fyre Festival. The danger is that organisers are so successful with their apps selling tickets that they forget to physically organize the real festival. It all becomes too money-driven and too big.

To conclude, music tourism will be increasing every year (if circumstances allow) because music festivals are there for everyone and can really add a sparkle to your life. If you want to escape from your daily routine or just want a fun weekend with friends, you can try a music festival. Music festivals can truly be magical. When it comes to me personally, I can say they have enriched my life.

References

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy. Theory, Culture & Society, 7, 295-310.

Becker, H, Naaman, M. & Gravano, L. (2009). Event Identification in Social Media. WebDB, 1-6.

Bennet, A. & Reterson, R.A. (2004). Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual. Vanderbilt University Press.

Connel, J. & Gibson, C. (2003). Sound Tracks: Popular Music, Identity and Place. Critical Geographics, 1-18.

Gibson, C. & Connel, J. (2003). ‘Bongo Fury’: Tourism, Music and Cultural Economy at Byron Bay, Australia. Royal Dutch Geographical Society KNAG.

Giorgi, L, Sassatelli, M. & Delanty, G. (2011). Festivals and the Cultural Public Sphere. Routledge.

Holt, F. & Antti-Ville, K. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Popular Music in the Nordic Countries. Oxford University Press.

Kazakulova, Y. & Kuhn, E. (2012). Communication Strategies via Social Media: The case study of Tomorrowland. Jonkoping University.

Kruger, S. & Trandafoiu, R. (2014). The Globalization of Musics in Transit: Music Migration and Tourism. Routledge.

Laing, D. (2009). World Music and the Global Music Industry: Flows, Corporations and Networks. University of Liverpool.

Lashua, B, Spracklen, K. & Long, P. (2014). Introduction to the special issue: Music and Tourism. Sage,.

Moline, A. (2019). Fyre Festival turns to ‘Fyre Fraud’. WorldPress.

Rudolph, K.F. (2016). The Importance of Music Festivals: An Unanticipated and Underappreciated Path to Identity Formation. Georgia Southern University.