This is ... a modern protest song vs a nationalist agenda

In this article, I take the protest song 'This is America' by Childish Gambino as a starting point for a discussion on the persepective it offers on current societal problems. By looking at some of the ‘localized’ adaptations of this protest song made by artists from around the world, we can gain an insight into different struggles around the world.

The protest song in superdiverse times

We are living in superdiverse times, times of hyper-globalization. Borders have opened up since the fall of the Berlin wall and the internet is at our fingertips. We can travel anywhere, as long as money and politics permits, and live in a world of relative freedom and safety.

Lucky for us, because most of us do not realize half of what is going on in the world. And yet many complain about refugees, the decay of norms and values, and the dangers and perils of walking the streets at night. How about they close the police station by 6:00 pm for security reasons? And what about the borders that have already been raised, for example, for those who are looking for a safer life in a safer country? (Coster et al, 2018).

Compared to the protests of Gambino and the like, what do nationalist movements in Western Europe bring to the table?

Really trying to understand the different existing versions of 'This is America' should at least give us an idea of the struggles that different societies are facing. When comparing these variations to Western European nationalists' attempts at making propaganda for their cause, we easily find that their claims have little to hold their own.

This is America

On the 5th of May – which coincidentally is Liberation Day in the Netherlands – of 2018, Childish Gambino published the protest song This is America on his YouTube channel, which quickly amassed millions of views and is currently approaching 400 million views. The video clip, in which Donald Glover (rap alias Childish Gambino) laments societal conditions in the United States of America with a special focus on the role of guns and the African-American relational history of the country. Where usually a war, a president, or some other singled out topic is being protested (e.g. Bob Dylan's Masters of War, or Aretha Franklin's Respect), Glover takes on multiple issues, combining them into one of the best, if not the best, protest song of recent times.

Guthrie Ramsey, professor of music history at the University of Pennsylvania, said in an interview with TIME: "The central message is about guns and violence in America and the fact that we deal with them and consume them as part of entertainment on one hand, and on the other hand, is a part of our national conversation." (...) "You’re not supposed to feel as if this is the standard fare opulence of the music industry. It is about a counter-narrative and it really leaves you with chills" (Gajanan, 2018). The combination of choral sounds, abruptly alternated with the trap style beat composed and produced by Ludwig Göransson and Glover himself, is only one of the ways in which the song and its accompanying visuals expresses its protest: by focusing on the a cappella choral parts in the beginning, Glover distracts the focus of what is really going on, or what is about to go on: the trap beat, the nasty truth behind the joyful distractions.

The moment, in the beginning of the song, when the a cappella choral music switches gears to the trap beat, the pose that Glover takes on when 'shooting' musician Calvin The II in the back of the head, is similar to a(n in)famous Jim Crow pose, a slave character personified by a blackface performer in the mid-19th century called Thomas D. Rice. Under the 'separate but equal' doctrine of the late 19th century, the Jim Crow laws took effect, separating 'white' and 'colored' people in society: in public toilets, restaurants, buses, public schools, at drinking fountains, and so forth (Fremon, 2000).

We all remember, or should have some notion, of Rosa Park's protest in 1955, when she refused to give up her seat in the paid colored section to a white person, because the white section had no free seats left. "By the terms of Alabama segregation, because there were no seats remaining in the white section, all four passengers would have to get up so one white man could sit down" (Theoharis, 2013: p.62). It may seem like Gambino is referencing to histoire ancienne, but keep in mind that the activity of 'sitting in a bus' was legally dependent on the color of your skin in the USA until 1965 – when the Jim Crow Laws were de jure abolished.

Still, it seems easy – yet painful – to imagine how the laws still affected public life in the years after, and still today. Gambino's 'killing of another African American man while taking on the 'Jim Crow pose' might well be a tripartite protest statement: ongoing discrimination of minorities, black on black crime, as well as gun violence. All in one shot.

A second visual protest, from which the viewer is actually distracted by Gambino and a group of dancers right behind him, concerns the people in the background who are rioting, falling down floors, and recording with their 'celly' from behind bars in plain T-shirts while an orange flickering glow lights up behind them. This seems to be a protest of how we are distracted by popular culture (dances like the 'Shoot', the 'Floss,' or the 'Roy Purdy Dance'), or being engulfed by social media and our phone screen, while still today there remains an ethnic gap in the U.S. prison population (Gramlich, 2018).

Even though the prison population gap is shrinking, over three quarters of the free U.S. population is from white origin, while only 13.4 percent of the population is of black or African American origin, according to the United States Census Bureau (2017). This implies that, even when the prison population would count equal numbers of 'black' and 'white' people, there still would be almost six times as many black people incarcerated, relative to the entire population. Glover is roughly saying: don't look away from the violence and the inequality that still remains to this day. Do not hide in the screens of your smartphones while adopting a blasé attitude, to use Simmel's (1903) words, towards what is going on in society. Because, this is America.

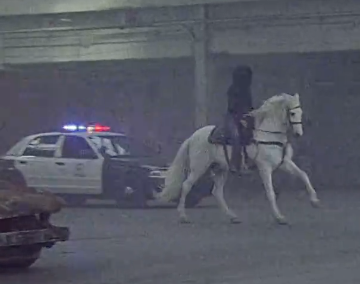

While I could point out the exact moments in the video clip that all of these things happen, I encourage you to look at the video carefully and interpret it by yourself as well. For me, for example, there is a clear moment where Glover refers to Johnny Cash, when ‘Death’ – or at least a hooded background character – appears to be riding on a white horse, followed by the cops. In The Man Comes Around, JC ends with the lines: “And behold, a pale horse, and his name that sat on him was death, and hell followed with him.” Be it my own interpretation, I am fairly sure that Glover and co. did not put the character in it on accident.

This is Nigeria, Iraq, Brazil... and others

Now, Childish Gambino's clip did not only spark international news agencies (e.g. de NOS, the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation) to publish about this protest song, it also inspired artists from other countries to answer Gambino by shedding a light on the situation in their countries. Many of these songs adopt, more or less, the same style and beat as This is America's. There are interesting cultural differences, but what is more important, these songs tell stories about other countries.

The first response came from Falz, a Nigerian rapper. This protest song focuses on safety issues, political corruption, Sars (Special Anti-Robbery Squad) brutality, abuse by religious clergies, and codeine abuse. The song must have pushed some of the right buttons, as it was banned by the country’s broadcast regulator, for being too 'vulgar' (Forrest, 2018).

The ingredients for the song and videoclip are clearly based on Childish Gambino's approach: the build-up, the warehouse, the dancing, among other elements reflect Gambino's protest song. But the issues addressed are very different. At one point, in the second verse of the song, Falz refers to the disappearance of 36 million Naira (or around US$100k), supposedly eaten by a snake, which was meant for the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board, a board that is conducting the entrance examinations for prospective undergraduates to Nigerian universities, which later turned out to be stolen by the superior of the accountant of the Makurdi state (Adaoyiche, 2018).

To emphasize the safety situation in Nigeria, Falz quotes a Twitter user, who is reduced to tears because 'the police station closes at six in the evening, for security reasons'. These reasons include the abduction of over a hundred school girls by Boko Haram (Lawal, 2018) and sponsored Fulani herdsmen killing in the Benue State since January 2018 (Fabiyi, Aluko and Charles, 2018). There are still many more references, both visually and textually, like the beheading of a man with a garbage bag over his head, to some extent similar to Gambino's first gun violence reference. In the Nigerian case, however, it is probably referring to beheadings by Boko Haram.

Another response to Gambino came from Iraqi rapper I-NZ, where we see an older man sitting down on a Persian rug to play the oud. The song begins with the same a cappella choral sounds as This is America, while I-NZ (a New Zealand citizen, born in Scotland to Iraqi parents, who also lived parts of his life in the UAE) sits down with the oud player. In the background two American soldiers start break dancing, who, by the end of the intro walk up to I-NZ, pick him up, and force him to shoot the old man. "This represents the transition from old and beautiful to all that is new and ugly as a result of the invasion of our country. This is represented by soldiers who forced the country into a war and destruction that it did not ask for," said I-NZ in an interview with VICE Arabic.

Halfway through the song, the Americans hand weapons to rebels, which immediately start forcing a soccer playing kid into a pick-up truck, presumably to take part in the bloodshed: "I'mma go train a kid, wash of the innocence". The Americans finally claim their mission to be accomplished, while leaving the Iraqi people to their own mercy.

The clip ends with I-NZ and the old man from the beginning of the clip, standing in the figurative blood that has been shed by the war, while a third person is 'cleaning' up the blood. The old man is citing the poem 'The River and the Death' by Badr Shakir al-Sayyab to I-NZ, representing the hope that Iraq will return to its former greatness, according to the rapper. "I tried to show this hope in the last shot, which shows Iraq's old and beautiful and poetic story, away from the pool of blood left by the invasion."

Many other artists have made a version of This is America, based on the views they hold about their respective countries, including Turkey's Fox, Sierra Leone's Xzu B, France's Zef who lament inequality, safety, and other topics in their songs. I urge you to watch them and reflect on the different issues the countries are facing in the eyes of the artists. To include all of them in this paper would be exhaustive and it also shows how difficult it is to be 'omniscient' about what is going on in the world, or even to stand in a vague shadow of such omniscience.

Finally, before heading to the discussion that is of importance in my opinion, I want to round up with a Brazilian version. This Brazilian version – there are more – begins exactly the same as the Gambino version: a guitar player, a warehouse, a person, filmed from the back, who walks to the now bagged guitar player and gets into the Jim Crow position to shoot him. From here on it gets different:

Although you might get a laugh out of it, the observation that the police are stealing (or worse) and has already sold the guitar player's guitar, is a comment on the corruption of the police in Brazil. Another comment on society is that the guy who keeps on dancing while just being shot in the leg by the police, must be on crack – an epidemic Brazil is struggling with as it passed to the no. 1 position on the list of consumers of crack cocaine in 2014 (Darlington, 2014). Even though in this protest song there is no room for any lyrics to be sung, it still addresses, albeit in a rather comedic way, a couple of issues of contemporary Brazilian society.

So far, I have only come across one female version of this protest song, made by YouTuber Nicole Arbour. Her version, however, got criticized for having little of the subtlety that Gambino's video has and that it basically is a bad idea to "...use a political song and turn it into a questionable plight for your cause" (Shamsian, 2018). Arbour later apologized, claiming she understood why people got offended, adding that that was never her intent. But hers is not the only version receiving criticism.

Jesse Lee Peterson (left) hosting a radio show

Donald Glover’s own original version received critique, albeit from a very different corner of society. Alex Jones, a paleoconservative – much like Donald Trump – and no stranger to conspiracy theories, said on his show ‘Infowars’ that This is America is “…emotional idiocy and people fittingly doing a voodoo dance (…) That is a voodoo dance he is doing.” Another radio show host, reverend Jesse Lee Peterson, who has urged the conservatives and the alt-right to unite to defeat evil, called the protest song and its video clip ‘pure evil’: “Because blacks call good evil and evil good. They see this evil stuff this guy is doing and they think it’s good (…) This is why most blacks are getting worse, because they love evil. They love it. They hate good.” Finally, the white supremacist website The Daily Stormer claimed that Glover was attacking America with his new track. (Warning: the article is racist and insulting, and the website could get banned after this article has been published - as has happened before.)

Is this what we want?

Much like the laments coming from the – more or less – liberal side of society, the opposite sides (including nationalist, fascist, and white supremacist movements) have videos with their own complaints about society. Flemish nationalist movement Schild & Vrienden (S&V), for example, uploaded a video on their YouTube channel in which members address what they think is wrong with society. The video has been taken offline due to copyright violations, but can still be seen in the Pano documentary about S&V.

S&V member stating: "I don't want a society which has forgotten about our norms and values."

But compared to the protests of Gambino and others, what do these nationalist movements in Western Europe bring to the table? After a few shots of protests worldwide, with the accompaniment of an ominous soundtrack, 'end boss' Dries van Langenhove asks the viewer whether this is what we want our future to be like. He is followed by a number of S&V-members, who are making claims like: "I do not want streets where women are not safe", "I do not want a society which has forgotten about our norms and values", "I do not want Sinterklaas without Zwarte Piet," and: "I do not want a Europe where Europeans will become a minority."

If your third biggest concern is that you have to change a traditional feast, compared to concerns about gun violence, terrorist attacks, invading armies and corrupt governments, you really do need the ominous music. Especially when the most important argument S&V seems to make is that 'we do not want streets where women are not safe'. That is to say: we do want streets where everyone is safe. However, 'our' streets are not nearly as unsafe as those of Iraq, Nigeria, or even the USA. In no way do I intent to downplay the progress that can still be made in Western European societies, but the members of S&V do not seem to have much of a notion of what is happening in the rest of the world.

Ergoism: when small 'bits' of evidence are irrationally being used to explain the bigger picture.

It seems that these S&V speakers are acting from a very ergoistic perspective (Blommaert, 2018). Ergoism (from Latin: ergo, meaning 'because' or 'therefore') occurs when small 'bits' of evidence are irrationally being used to explain the bigger picture. An example: a terrorist, related to IS, has committed a suicide attack, ergo - therefore - Islam is an evil religion.

The versions of This is [a country] that have been discussed are different from S&V’s footage, at least in the sense that they are much less ergoic. Gambino addresses gun violence, yes, but not in a ‘therefore-sense’. It is what is happening (cf. Mass Shooting Tracker) and the result of it is bad. Notice how it does not make an all-encompassing claim about society or the safety on the streets. If my interpretation about ‘Death’ on a white horse is correct, then this might be an ergoic statement about law enforcement in the USA, however, it seems to be more of a metaphorical one – rather than a baseless claim about the general safety on our streets). When Falz is making claims about herdsmen killing people, or government officials stealing money, it is not an overgeneralization of society.

"And behold, a pale horse."

If S&V would have made their claims more rational, then it might have been different. "We think that there are too many occasions where women get harassed or attacked" is a rational claim, because even one attack or harassment – whether on the streets or anywhere else – is bad. The question, though, is whether you can entirely weed out all outliers and make the streets one hundred percent safe. I think that it is a reasonable wish, but an irrational goal.

The discrepancy between rationality and reasonability (Blommaert, 2018) is what alternative facts, propaganda, and demagogues strongly rely on. The problem is that reasonability, rather than rationality, is influencing how many people interpret the world in a high-speed information society. More in-depth analyses of this difference will have to be the topic of future articles, because it is too important to reconcile with it in one single paragraph. What we can take away from the current discussion is that we can deepen our rational understanding of the world around us, by listening to the voices of Gambino, Falz, I-NZ, and others, while we should not get carried away by the dysphemistic voices of the likes of S&V and other nationalist movements trying to push their agenda.

Maybe it is time for a new revolution fueled by another powerful soundtrack like the one of the sixties – one that can still be heard today. A soundtrack that makes us more rationally aware of the world around us, not just by listening to populist voices that hijack the media with outrageous statements and blatant overgeneralizations and lies, but by listening to those people that are really in the midst of it all. As Bob Dylan once wrote: "Your old road is rapidly aging. Please get out of the new one, if you can't lend a hand, for the times they are a-changing."

References:

Adaoyiche, G. (2018). How JAMB coordinator 'swallowed' N36 Million.

Blommaert, J. (2018). Ergo: exploring the world of alternative facts.

Coster, A., Dijsselbloem, J. Gorp, M. van & Smits, L. (2018). Pricetag for a 'better' life: tangible and intangible borders that refugees have to deal with.

Darlington, S (2014). Brazil wrestles with crack epidemic as it gears up for World Cup.

Forrest, A. (2018). ‘This is America’ parody banned in Nigeria.

Fremon, D. K. (2000). The Jim Crow Laws and Racism in United States History. Berkeley Heights, USA: Enslow Publishers, Inc.

Gramlich, J. (2018). The gap between the number of blacks and whites in prison is shrinking.

Lawal, I. (2018). How insecurity is ruining education in Nigeria.

Gajanan, M. (2018). An Expert's Take on the Symbolism in Childish Gambino’s Viral ‘This Is America’ Video.

Olusola, F., Aluko, O. & Charles, J. (2018). Benue: Killer herdsmen are sponsored, says military.

Shamsian, J. (2018). A YouTuber made a 'Women's Edit' of Childish Gambino's 'This is America' music video — and it's terrible.

Simmel. G. (1903). The Metropolis and Mental Life. In Wolff, K. (Trans.) The Sociology of Georg Simmel. New York, USA: Free Press,

Theoharis, J. (2013). The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. Boston, USA: Beacon Press.

United States Census Bureau (2017). untitled.