When do the critics of Zuma cross the line? Should rape be used as a political statement?

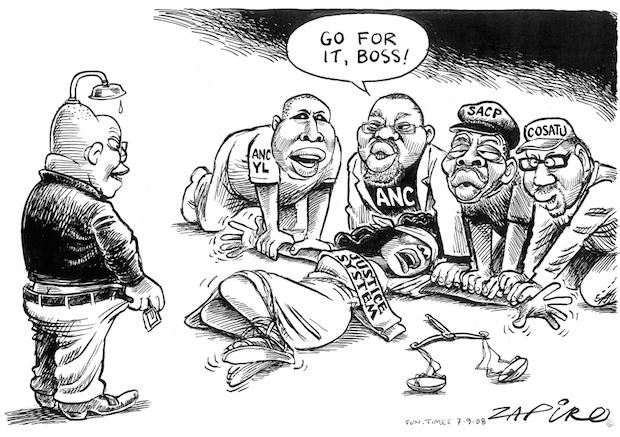

South African cartoonist Zapiro was criticized for his satirical portrayal of the South African president and his cronies ‘raping’ the country. A week later, Ayanda Mabulu, a controversial artist, released his own portrayal of the president, essentially, ‘raping’ Nelson Mandela as another political metaphor. To make matters worse, the painting was titled 'The Economy of Rape.' The former was criticized for portraying South Africa as a Black woman being raped, while the latter was considered ‘distasteful’ with regards to the degrading of Mandela’s image.

Furthermore, the Nelson Mandela foundation agreed with most of the twitterverse that the painting is 'distasteful', while also advocating the artist's right to free speech. Some even said that in the painting Mandela is merely being 'screwed', but not raped. Either way, reactions to each portrayal of sexual abuse were more nuanced than they deserved to be.

A tweet about the now infamous painting by Ayanda Mabulu.

How we got here

In 2005, the daughter of one of Jacob Zuma’s friends accused the president of rape. In 2006, he was acquitted, stating that the act was consensual. During the trial, Zuma also stated that he was aware that the woman was HIV-positive, but that he ‘took a shower’ to combat transmission. This statement earned Zuma the showerhead totem, which Zapiro was the first to immortalize.

The first of four of Zapiro's depictions of Zuma raping featured 'Lady Justice' as the victim.

The president sued Zapiro over his depiction of Zuma raping Lady Justice. It was the first of four cartoons portraying rape as a political metaphor. Zuma later withdrew the charges, under pressure from the South African constitution’s free speech stipulations. However, throughout the years South Africans have been divided about Zapiro's Jacob Zuma rape depictions, often along racial lines. The most recent rape cartoon was published after the country’s downgrade to junk status.

Theorizing rape representations: The Holocaust effect

The theorization of rape in artistic expression is virtually non-existent. This is especially true for the artistic expression of politics in such a symbolic way. Since South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution was underscored by the oppression of the subaltern, it protects artistic expressions of any kind, unless it is considered to be racist or hate speech. After all, racism and hate speech are human rights violations. Insofar as art and design are concerned, these kinds of human rights violations have not yet occurred, despite social media concerns over the content of these artworks. This forces us to look at other forms of trauma in order to find answers.

Some may argue that comparing the World War II Holocaust to rape may be inappropriate, but in the absence of theory that corresponds with the artistic use of rape as a political metaphor, it is an unfortunate necessity. Comparing rape and the Holocaust would indeed be like comparing the trauma of surviving a terrorist attack to that of escaping a year of sex slavery. Each trauma is different. So while the notion of comparing traumas is sensitive in nature, under the current circumstances it seems society does require a paradigm through which to view trauma as a monumental tree with intricately linked branches; a universal phenomenon with a variety of unique experiences and reactions. Additionally, it is glaringly significant that rape was used as a weapon during the Holocaust.

So with the over-arching concept of 'trauma' in mind, Van Alphen's work on Holocaust depictions became a useful paradigm through which to view Zapiro and Mabulu's cases. Describing trauma as 'horror' and 'extreme experiences' he said: “The extreme horror of the historical reality causes language to fall short ... representation does offer the possibility of giving expression to extreme experiences ... representation is not a static, timeless phenomenon, of which the (im)possibilities are fixed once and forever. For every language user, representation is a historically and culturally specific phenomenon. Languages, whether literary/ artistic or not, are changeable and transformable.” Victims' experiences of the Holocaust were in every way particular, but through representation they can be transformed, legitimized and evolved to create societal awareness and even empathy.

Therefore, Van Alphen’s analysis of Christian Boltanski’s ‘Intervention in Holocaust Historiography’, using the Holocaust effect, became a useful conceptual framework for critically evaluating Zapiro and Mabulu's rape depictions. This effect encompasses “conjunction of [the] use of reenactment (concerning the practices of the perpetrators) with the overwhelming awareness of the total loss it evokes (concerning the victims of Nazism).” In other words, reenactment, however graphic, while factual and honest, can reduce the gap between the victim’s sense of trauma and the power that the perpetrator continues to hone over their victim long after the harrowing event. As an audience, we become privy to trauma when the depictions are honest. As a victim, the depiction itself can become traumatic, unless honest. Both Zapiro and Mabulu's depictions of rape were in no way factual or honest.

A symbolic representation’s reconstruction of a rape narrative into a concept, metaphor or myth renders the trauma untrue and illegitimate.

One could almost say that a more empathetic reenactment of an event is required. It can potentially evoke the narrative, or the “language” many are unable to retell after experiencing a traumatic event. It could empower a victim who is otherwise unable to relate. Unfortunately, Zapiro and Mabulu fell short on resonating with South Africans in such an empathetic way. As van Alphen tells us, “the experience of an event is already a representation; it is not the event itself.” A symbolic representation’s reconstruction of a rape narrative into a concept, metaphor or myth renders the trauma untrue and thus illegitimate. Symbolism exacerbates the victim’s continuous suffering or their personal mental representation of the event itself, because the lack of an unembellished representation from an artist with a political agenda, denies the victim conceivable internalizations of that trauma. Isn't art meant to empathize?

Applying the Holocaust effect

Recently, the Netflix series ‘13 Reasons Why’ generated mixed reactions as a result of its raw depiction of teen suicide and rape. Despite the divided reactions, it was celebrated for unearthing some of the myths of teen suicide and rape. While this is a TV show and not a photographic exhibition such as the object of van Alphen’s analysis, we can look at his explanation of how two aspects of this type of depiction are “appropriate” using the Holocaust effect: “... for most critics and scholars active in Holocaust studies the artistic and literary genres that are most appropriate – most effective and proper – to depict the Holocaust are those that are realistic par excellence, those that do not attempt to fictionalize history but that offer history in its most direct, tangible form: to wit, testimonies, autobiographical accounts, and documentaries. This preference is based not on aesthetics but on moral grounds.” Although the Holocaust was an event that affected a specific group of people, suicide and rape transcend gender, racial, cultural and national lines; it’s a global phenomenon. As a television series ‘13 Reasons Why’ is based on a series of teen novels and not on a historical event. The series stakes its claim to the “moral imperative” of rape representation through mimicry and reenactment of a more empathetic kind.

Thus the series portrays rape and suicide as simply that: rape and suicide, rather than symbolic of something romantic in nature, such as a political agenda.

For example, the creators ventured outside of the boundaries of its book counterpart. They stuck to the suicide narrative, rather than mimicking a botched attempt at suicide as it happened in the book. In the television series, the protagonist thus died in suicide and the frightening finality of the act was not romanticized. Instead, it flouted the norm based on the viewers' constant need for a happy ending.

In reality suicides lead to death - when executed correctly. Thus the series portrays rape and suicide as simply that: rape and suicide, rather than symbolic of something romantic in nature, such as a political agenda. One could say that it reenacts, mimics and thus reconstructs rape as a universal phenomenon, using its fictional high school setting as its “tangible form”. Where was the “tangible form” in Zapiro and Mabulu’s rape representations? Instead, many viewed the depictions for what they were: representations of rape, regardless of intended symbolism.

Furthermore, social media reactions to Zapiro and Mabulu’s respective works revealed a harrowing double standard in the conversation about the unrepresentability of rape in artistic expression: male rape turned out to be a non-factor. In Zapiro’s depiction, a woman is the victim. In Mabulu’s depiction, a man (Nelson Mandela) is the victim. The response to both works was different. Why is that?

The legal dispensation in South Africa for years perpetuated the male rape myth under legislation regarding sexual offences, until 2007. The use of gender was subsequently removed from the legislation completely, recognising all acts of rape regardless of gender. According to the ‘Analysis of National Crime statistics 2014/ 2015’, “Under the previous definition of rape, the crime referred to the vaginal penetration of a female by a male sexual organ. The [amended] Act expanded this to include the penetration of a whole range of bodily orifices by various objects and has no reference to the genders of the victims or perpetrators.” Similarly, the USA’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) recently changed their definition of what constitutes rape. So it is no surprise that the idea that females are the only victims of rape is still a problematic notion today, under circumstances where male rape has only recently been recognised as a crime and the stigma associated with male rape supercedes the importance of the legislation.

The unrepresentability of rape is directly proportional to symbolic agendas

Without delving into the aesthetics of the painting and the cartoon, we can target the political agendas that diminish the plight of the victim through the symbolic use of rape as a representation. The use of rape in this unforgiving way must stop. If we allow trivial forms of art to penetrate conversations about traumatic matters such as rape, we perpetuate rape culture and the desensitization associated with it. Why else would social media omit the male victim from their disgust at Mabulu’s painting, which depicted the image of someone we can all recognise, and instead focus on the victimization of a female who symbolized the country through an anonymous, yet recognisably black body in Zapiro’s cartoon?

The use of rape in this unforgiving way must stop.

We can only ask this question if we strip these artworks of their concepts, such as the use of the body of a black woman, and the body of a black man. We can only ask this if we juxtapose the two representations in terms of how an anonymous woman is used in the one and the image of Mandela, a symbol of moral superiority, is used in the other.

Additionally, Mabulu’s painting reconstructed a victim of sexual abuse that was meant to represent a person who spent 27 years in prison, where rape culture thrives, no less. Yet, Zapiro’s cartoon similarly trivializes the act of rape by symbolically using the act under notions of emotional hegemony, which is closely related to emotionally driven politics. The series ‘13 Reasons Why’ at least attempted to empathize with victims of rape.

While it would be considered a war on culture to police an artist’s freedom of expression, it is our responsibility as a society to create awareness on the implications of problematic artistic representations of victimization. However, first of all we all should agree that it is the artist’s responsibility to use their art to empathize, acknowledge and legitimize the plight of victims of heinous crimes, such as rape.

References

Alphen, E. . (1997). Caught by history: Holocaust effects in contemporary art, literature, and theory. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

Alphen, E. (1999). Deadly historians: Boltanski's intervention in holocaust historiography. Memory Et. Oblivion / Ed. by Wessel Reinink, Jeroen Stumpel, 913-917.