Who are the Black Pete supporters?

Saying the words "Black Pete" has been a bit controversial in the Netherlands for the last few years. A media storm has hit the Low Countries since the protest group Kick Out Zwarte Piet (KOZP) started to protest during the celebrations for the arrival of Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas) close to Christmas. But a counter movement started rising as an answer to the KOZP. This group, which I will call the Black Pete Supporters (BPS) is becoming more and more active in the on- and offline world. In this article, I will take a look at how and why the BPS started to campaign for keeping Black Pete black.

What is the tradition?

Sinterklaas is a national celebration in the Netherlands with a long history. It goes back to the celebration of the old Germanic god Wodan (Odin) who flies in the sky on his eight-legged horse. He has two black ravens who tell him what’s happening down on earth. But during the Christianization of Europe in the early Middle Ages, monks replaced Wodan with Saint Nicholas, who was born in Smyrna (Turkey) and died (probably) in 343.

Over the centuries, new traditions were formed around this celebration. For instance, Saint Nicholas would throw money around for the people when entering a house - a tradition in which money is now replaced by candy. Similarly, the omniscient ravens of Wodan, who knew exactly what happened on earth, were replaced by Saint Nicholas' "big book", which is a record of whether a child has behaved well or badly during the past year. However, after the Netherlands became mainly protestant during the Reformation in the 16th century, the celebration of Saint Nicholas became less important. Around the 19th century, the festivities around him returned, with people dressing up as the saint himself. The first official arrival of Saint Nicholas was held in Amsterdam as late as 1934.

Wodan

But one particular tradition is getting a lot of attention these last years: that of the servant Black Pete, who helps Saint Nicholas in distributing presents for children across the Netherlands. This Black Pete character has had, since the beginning of the 20th century, a black face, red lips, golden earrings and an afro haircut. Where do these features come from? It’s hard to trace their origin exactly because there are many possible sources, but an important one is a book about the saint, published in the Netherlands around 1850 called St. Nikolaas en zijn knecht (Saint Nicholas and his servant) by Jan Schenkman. Schenkman added some new elements to the legend of the saint: his horse, the steamship on which he arrives, and his black servant. It is not certain whether Schenkman made up these new "traditions" himself or whether he drew on already existing ones. The fact is that after the publication of this book - and many more books after this one - the new traditions became widely popular in the Netherlands.

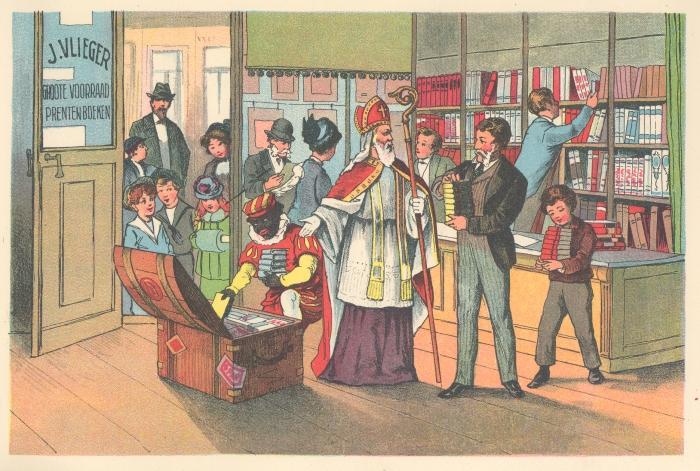

An image from J. Schenkmans' book.

In the 1950’s, the arrival of the saint was broadcast live on national television for the first time and the festivities around the saint became larger and larger. Today, they constitute a big commercial festival as well. Supermarkets in the Netherlands make a lot of money the week leading up to Saint Nicholas on December 6.

But KOZP started to protest these traditions by protesting at arrivals of the saint in different cities. The all-time low in the tensions that ensued was reached in 2017 when Frisians blocked a highway in the north of the Netherlands in an effort to stop anti-Black Pete protesters from entering the city. This resulted in a big traffic jam and in unsafe traffic conditions. The police, however, did not break up the blockade despite the protesters being allowed to protest by the local mayor. What are the demands of KOZP? They want everything except a black Pete. Pete can have chimney wipes or be painted in different colors - for them it doesn’t matter - but he should not be black. Their opponents, in contrast, want to have Black Pete as black as possible. So, who are these suporters and why would they want to keep things the way they are?

Who are the Black Pete Supporters?

There are many Facebook groups and Instagram accounts for Black Pete Supporters. There isn't exactly one big organization around their ideas, but there are a lot of different groups and subgroups. In this article, I use Black Pete Supporters (BPS) as an umbrella term to refer to all the various pro-Black Pete groups. Their main goal is to keep the so-called tradition of Black Pete alive. They try to achieve that by sharing images, texts, news links and memes with other followers of the cause. Individuals thus come together in their self-made online world of BPS. They have formed an imagined community, where they meet each other online, althrough they will probably never see each other in the offline world. This community is "imagined" precisely because its members will never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each one of them lives the image of their communion (Anderson, 2006).

These traditions are important for them because they symbolize the nation; the BPS are, in that sense, nationalists.

So how does one recognize Black Pete Supporters? Simple: they share a lot of content about Black Pete. If they find an article that demonizes the KOZP supporters, there is a big chance they will post it. Another indexical (an attribute that is needed to recognize a particular social group) is the language Black Pete Supporters use when commenting on Facebook posts. Of course, it’s not just their language, but also the opinions they share with each other. Some examples follow below.

Screenshots from "Eindhoven Maintains Black Pete" on Facebook

Translation, image on the left: "Black Pete is not racist." The first comment reads: "I reguraly buy old Saint Nicholas books with Black Pete in it and Black Pete dolls. I don't have much to spend, but it gives me the feeling that not everything is lost and forgotten." The second: "Why do we all accept this? Soon or later our tradition is lost for ever." On the left side we see BPS calling KOZP a terrorist group. They also blame the mayor of Eindhoven.

What most comments have in common and what basically is the overall argument is that people don’t want to lose another "tradition". To the BPS, Black Pete is a tradition that has to be maintained. It is also political. Take a look at the screenshot below, where you can see the BPS don't want anyone to take away their culture. They use the colors of the Dutch flag as a symbol of the nation-state.

"Black Pete is not racism. Don't touch our culture!" - Eindhoven Mantains Black Pete on Facebook

What is tradition?

According to the Oxford Dictionary a tradition is "a belief, custom or way of doing something that has existed for a long time among a particular group of people." This is not a particularly clear-cut definition as the explanation consists of three key elements: it’s a "belief", a "custom" existing "for a long time", and it exists "among a group of people". When we look at Saint Nicholas in general, we can say that this is a tradition with a long history among the Dutch population. Can we say the same of Black Pete? This character was added to the existing tradition just around 100 years ago, and we can argue that Schenkman created a new tradition in addition to Sinterklaas. What originally was a cultural tradition, is now transformed by Black Pete Supporters into an "invented tradition", a constructed and formally instituted tradition (Saint Nicholas) and a less easily traceable tradition within a brief and dateable period (Hobsbawm & Ranger, 1983). They made the black servant more than just a servant, they made him a symbol for the Dutch culture and nation.

So, it looks like Black Pete is a relatively new tradition. Yet some people believe Black Pete did not appear out of nowhere. Take a look at this video:

Historian Han van der Horst believes Black Pete is in fact an adapted tradition, because he represents the devil. Take a look at the north of Italy, where people also celebrate Saint Nicholas, but where he is accompanied by a devil-looking figure called Knecht Ruprecht. It is a figure much like Black Pete: he punishes naughty kids with a rod.

Knecht Ruprecht

Why call Black Pete a tradition?

Black Pete supporters often see the KOZP as a danger to the nation as seen in the screenshots below. Traditions are, according to them, important for "keeping the Netherlands Dutch".

Comments on a Facebookpost about Black Pete.

The first comment translates to: "I only know four people who have spoken or are speaking the truth: Nostradamus, Pim Fortuyn, Theo van Gogh and Geert Wilders." The second: "Everyone, place Black Pete's in your garden, balcony, window or car. That person [probably Silvana Simons red.] is a treath for our society. She has to be forced to go to a mental hospital and then [they should] throw away her key. Why is such trashy figure in our council and where are our traditions and culture going?"

It also looks like the BPS are politically oriented towards right-wing and anti-mainstream-media. We can see that it’s likely that pro-Black Pete people will also be proponents of keeping firework a tradition during New Year’s Eve and maintaining the bonfires in The Hague. Those traditions are important for them because they symbolize the nation. The BPS are, in that sense, nationalists. “Having a national identity also involves being situated physically, legally, socially, as well as emotionally: typically, it means being situated within a homeland, which itself is situated within the world of nations” (Billig, 1995). The BPS are not only physically but most of all emotionally connected to the Netherlands.

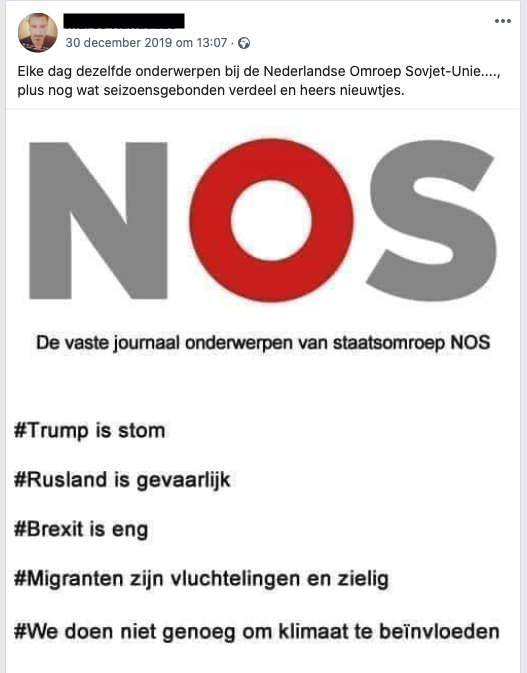

NOS (Public News Organization) = fake news, according to the BPS.

Translation: (a) caption: "Everyday the same topics of the Dutch Soviet-Union Broadcoaster, including some divide and conquer-topics." (b) image: "Some standard opinions of the NOS: #Trump is stupid, #Russia is dangerous, #Brexit is scary, #Migrants and refugees are pathetic and #We don't do enough to change the climate."

As I stated earlier, I noticed that a lot of Black Pete Supporters are politically aligned with the right. They mention names like those of Pim Fortuyn (former Dutch politician), Geert Wilders (Party of Freedom) and Thierry Baudet (FvD), politicians who all made Black Pete political by labeling it a Dutch cultural "tradition". But this doesn’t exactly mean that all the BPS are right-wing; some also can simply appear to be "protecting" their nation. In Banal Nationalism, Michael Billig (1995) mentions the Falklands and the Gulf wars. According to Billig, the protagonists in those wars were not fighting for a god or a political ideology, but claimed to be fighting for their nation.

Most of the Black Pete Supporters also just want to keep the Netherlands as they know it. But the hardcore supporters are not only unhappy with Black Pete becoming less black; for them there are more problems, they are hot nationalists. As Billig (1995) also states: “the aura of nationhood always operates within contexts of power”: the power of other countries around the Netherlands, but also power within the Netherlands in this case. It appears that these hardcore Black Pete Supporters are unsatisfied with the current state of affairs in Dutch politics and the people who are in power. Also, the people in power control the mainstream media, it is argued. As seen in the screenshots, Black Pete Supporters are having a hard time believing current mainstream media such as the Dutch national broadcasting network NOS. They see themselves probably as outsiders, people who do not live conforming to the rules and norms of the mainstream (Becker, 1963). But, on the other hand, they see people who are against Black Pete as outsiders as well.

A video of Geert Wilders' Party of Freedom, where they promote Black Pete as a tradition.

Why is nationalism important for Black Pete supporters?

For Black Pete supporters, the nation - including its traditions - is a key part of their identity. Their identity discourse (a set of rules, norms and specific traits that make up an identity, according to Becker, 1963), is the answer to the question "what does it mean to be Dutch?" For them, traditions like Black Pete are part of being Dutch. We have to imagine that Black Pete has been in people's lives for many years; in commercials, in shops and supermarkets, as well as in the minds of children, Black Pete was present everywhere. Even if you’re not a nationalist at all, you would see Black Pete as a "traditional" Dutch phenomenon intergrated in the customs of Dutch society. That's different than hot nationalism, it is more banal nationalism: "not a flag which is being consciously waved with fervent passion; it is the flag hanging unnoticed on the public building" (Billig, 1995).

Nowadays, we can view the support for Black Pete as a form of hot nationalism, instead of banal nationalism. Through the weaponization of the tradition, Black Pete became more than just a symbol of Dutch culture: he became a symbol for a nation, at least for the hot nationalists. They politicized Black Pete in the service of "defending" their Dutch nation.

The differences between KOZP and Black Pete Supporters are likely to grow even more into an "us" vs. "them" template.

The social group of hot nationalistic Black Pete Supporters is not exactly a new phenomenon, but the way the group was formed is a new appearance. Because of the intensity of mediated communication among members of this group, these members imagine themselves as being part of a national community (Maly, 2019). This also means that the differences between KOZP and Black Pete Supporters are likely togrow even more into an "us" vs. "them" template. Social media have an important role in forming these communities. Nations even thrive because of internet becoming a key technology (Eriksen, 2007).

Today a lot of media outlets have banned Black Pete from their medium. RTL, for instance, decided not to show Black Pete in any TV show anymore, NTR is still changing its Pete's from black to chimney wipe, and even stores like De Bijenkorf and HEMA decided not to use the Black Pete in their commercials or product designs anymore. This, of course, can be seen as a victory for the KOZP supporters, but the latter are not stopping untill the black stereotypical racist figure is gone. According to Black Pete Supporters, this is proof that KOZP wants to destroy Dutch culture. This is why the discussion is still going on today, with Black Pete Supporters feeling as if they are being betrayed by media, by shops and even by some politicians who publicly condemn Black Pete. Therefore, it is not strange to see Black Pete supporters turning to online fora to meet likeminded people and to share posts from Thierry Baudet and Geert Wilders - politicians who bank on the feeling that the Black Pete supporters have: that they are becoming strangers in their own country.

References

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Communities. In Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (pp. 1-7). London: Verso.

Bahara, H., & Esseroili, N. (2019, November 15). Zo werd het pro-Zwarte Piet-protest steeds gewelddadiger. Retrieved December 2019, from Volkskrant.nl.

Becker, H. S. (1966). Outsiders, Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Billig, M. (1995). Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Blommaert, J. (2014). Ethnography, superdiversity and linguistic landscapes. Chronicles of Complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Blommaert, J., & Dong, J. (2009). Ethnographic fieldwork. A beginners guide. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Eliot, T. S. (1982). Traditions and the Individual Talent. In Traditions and the Individual Talent (Vol. 19, pp. 36-42). The MIT Press on behalf of Perspecta.

Eriksen, T. H. (2007). Nationalism and the Internet. In Nations and Nationalism (Vol. 1, pp. 1-17). London: ASEN/Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Glassie, H. (1995). Tradition. The Journal of American Folklore, 108(430), 395-412.

Hobsbawm, E., & Ranger, T. (1983). The Invention of Tradition. In The Invention of Tradtion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koninklijke Bibliotheek. (sd). Sinterklaas. Retrieved December 2019, from KB.nl.

Maly, I. (2019). SGDW - class 4 - the construction of the mainstream 2019-2020.pptx. PowerPoint. Google Drive.

Müller, L. (2012, October 22). 'Piet was waarschijnlijk een gelijkwaardige partner van Sinterklaas'. Retrieved December 2019, from Volkskrant.nl.

Varis, P. (2014). Digital Ethnography. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies.