Why Voices from Chernobyl is a must-read you will never forget

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster hit Ukraine during the Soviet period, on the 26th of April 1986. The tragedy changed the history of Europe and impacted the lives of thousands, leading to numerous deaths and the spread of dangerous disease and complicated health issues. The devastating tragedy also influenced the way Europe sees nuclear energy today. Michail Gorbachev has himself admitted that the Chernobyl disaster drastically influenced the State and fastened the process of the Soviet Union's collapse (Stern, 2013).

The Chernobyl Power Plant incident has been labeled the “largest technological disaster of the twentieth century” (Alexievich, 1997) and is often referred to as the worst accident in the history of nuclear power. The series of explosions occurred as a result of a safety experiment on maximum power increase at Energy Block #4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station, or as it was officially called at that time, the Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant. The explosion completely destroyed Reactor #4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The exploded Energy Block #4.

The scale of the radiation spread

As a result of the explosion, the scale at which radiation was emited was so big that it affected the whole globe. The countries that suffered most from the tragic outcomes were contemporary Belarus and Ukraine. The nuclear station was located near the Ukrainian-Belarusian border, at a distance of around 16 km from it. The location of the Power Plant and the wind streams on the days after the explosion became the reason why Belarus suffered the most from the radiation. “For tiny Belarus (population: 10 million), it was a national disaster” (Alexievich, 1997). Because of the radiation, the government “lost 485 villages and settlements. Of these, 70 have been forever buried underground” (Alexievich, 1997). The consequences of the tragedy had long-lasting effects with hundreds of thousands of resettlers and endless kilometers of territories that will most likely remain uninhabited.

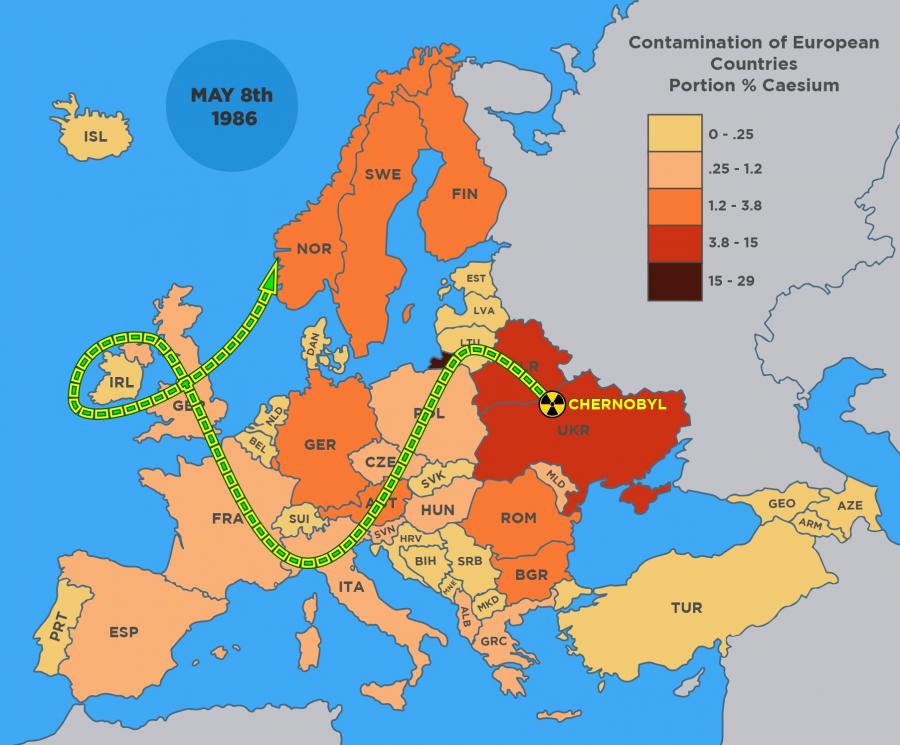

The tragedy, however, affected more countries and their citizens (Figure 2). The day after the explosion, the high radiation levels were measured in Germany, Poland, Romania, and Austria (Alexievich, 1997). In the following days, the radiation kept spreading throughout the world. From Switzerland, Italy, the Netherlands, France, Belgium, the UK, and Greece, it reached Israel, Kuwait, and Turkey on the 3d of May (Alexievich, 1997). “Gaseous airborne particles traveled around the globe: on May 2 they were registered in Japan, on May 5 in India, on May 5 and 6 in the U.S.” (Alexievich, 1997). In less than a week, Chernobyl had become a problem for the entire world (Alexievich, 1997).

Figure 2: The level of contamination of the European countries after the explosion.

The tragedy left millions of people affected. Ordinary citizens were exposed to the radiation sometimes unknowingly. Countless people participated in the recovery operation at the power plant, with the amount of “workers recorded in the registries appear[ing] to be about 400,000” (Nuclear Energy Agency, 2002). To date, the exact number of all the health-related complications people experienced, including deaths, is impossible to measure due to the lack of rigorous documentation and access to relevant sources.

Voices from Chernobyl by Svetlana Alexievich

Nobel Prize laureate Svetlana Alexievich's book Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, published in 1997, deals with the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. In the book, Alexievich has captured over 500 stories of victims of the tragedy. Voices from Chernobyl is based on interviews with people of different professions, ages, backgrounds, social positions, and life stories. Their stories are connected by a common reference point - the day the Chernobyl Power Plant explosion happened.

Alexievich has given voice to those affected by the tragedy through this literary work. Voices from Chernobyl opens with the translator's preface and then introduces the reader to the stories with historical notes and a prologue by the wife of one of the firefighter liquidators, Ludmila Ignatenko, whose story was picked up and popularized by the HBO series Chernobyl (2019).

The book is then divided in three parts: "The Land of the Dead", "The Land of the Living", and "Amazed by Sadness". The chapters present numerous interviews with liquidators, their relatives, people who opted to stay in the Chernobyl region after the explosion, children, scientists, school teachers, and others that experienced the nuclear disaster up close one way or another. The book then concludes with an epilogue, penned by the author.

What is very prominent is how Alexievich has chosen to highlight the role of the victims of the tragedy by barely interfering as a narrator in their stories. While being engaged with the book, the reader has a feeling that the victims are talking to someone, but the role of the author remains minor, almost unnoticed. At the end, Alexievich shares her experiences conducting the interviews. The author highlights her personal role in the process as that of a spectator of the tragic outcomes of the radiation incident.

The book is thus highly personalized. Based on true stories, it serves as evidence of what has happened as a result of the nuclear tragedy in 1986. The interviewees get personal with the author and share their deepest emotions and their most bitter memories with her. The readers thus have a chance to get a glimpse of what happened in the Chernobyl nuclear disaster from multiple perspectives.

Chernobyl: the State and the victims

The value of Alexievich's book also lies in the fact that it carries historical truth in it. At the time the incident occurred, the Soviet regime, with its censorship of the press, did not intend to spread the news in order to prevent mass panic and disbelief in the power of the regime. Even through the way people react in Alexievich's book, the readers can feel the lack of awareness about the dangers of the radiation in the areas near the power plant. For many, the nuclear reactor was just a place where "magic was made", which created an electricity supply (Alexievich, 1997). People living in the city of Prypiat and the areas near the region were not aware of the potential dangers they could face.

Figure 3: The abandoned city of Prypiat.

The immediate reaction of the local authorities after the explosion was to stop the fire at the station. Unfortunately, the firemen were not prepared or properly informed about what was going to happen after their last shifts at the station. The wives of the liquidators later shared the horrific stories of their husbands’ deaths. At first, loving women had a hope to somehow help their significant others: “All the wives got together in one group. We decided we’d go with them. Let us go with our husbands! You have no right! We punched and clawed. The soldiers - there were already soldiers - pushed us back” (Alexievich, 1997).

However, for most of the sufferers who got high doses of radiation, it was already too late. Soon it became clear that the state of their health was only getting worse and hope was slowly dying: “He started to change - every day I met a brand-new person. The burns started to come to the surface. In his mouth, on his tongue, his cheeks - at first there were little lesions, and then they grew” (Alexievich, 1997). After many hours beside their husbands, women would hear words of despair: “You have to understand: This is not your husband anymore, not a beloved person, but a radioactive object with a strong density of poisoning. You’re not suicidal. Get ahead of yourself” (Alexievich, 1997). Many admitted that they could not love anyone anymore as much as they loved their husbands who died after the radiation devastated their bodies. After their deaths, the hospital in Moscow was completely renovated and rebuilt due to the high remaining radiation levels (Alexievich, 1997).

Meanwhile, citizens of Prypiat were still not aware of the dangers of the explosion they could see from the windows of their apartments. While firemen liquidators were immediately hospitalized, “no one talked about the radiation. Only military people wore surgical masks” (Alexievich, 1997). The authorities started preparing citizens for the evacuation. Some of the individuals recall: “It’s night. On one side of the street, there are buses, hundreds of buses, they’re already preparing the town for evacuation, and on the other side, hundreds of fire trucks. They came from all over. And the whole street is covered in white foam. We’re walking on it, just cursing and crying” (Alexievich, 1997).

State censorship and forced patriotism

As a result of the Chernobyl explosion, the State took measures to lower the spread of information on the tragedy, its dangerous levels of radioactive elements released, and the possible outcomes of the ecological catastrophe. “In the process of abstraction [of the medical narrative and the human toll of the disaster], an act of political domestication ensued: the story of the human effects and the massive number of workers it actually took to contain Chernobyl-related contamination was relegated to the domestic sphere of Soviet state control” (Petryna, 2013).

Generally, there was a lack of information covered by the news media. For the first couple of days, “the Kremlin kept silent, until inquiries from the Swedish government made it impossible to deny that something went terribly awry in Ukraine” (Golinkin, 2016). However, even then, the announcement that took place lasted for twenty seconds, “explaining there was an issue at Chernobyl and the authorities were handling it” (Golinkin, 2016).

“The robots couldn’t do it, their systems got all crazy. But we worked. And we were proud of it” (Alexievich, 1997).

Numerous stories in Alexievich's book serve as evidence to the complete lack of awareness among the population regarding the dangers they were unwillingly exposed to. The soldiers share the heroic stories of how they helped in the liquidation efforts: “The robots couldn’t do it, their systems got all crazy. But we worked. And we were proud of it” (Alexievich, 1997). The citizens of Prypiat did not understand why they had to leave their homes. People from nearby villages asked soldiers to let them stay in their houses. In the book, one of the re-settlers shares: “At first, I waited for people to come - I thought they’d come back. No one said they were leaving forever, they said they were leaving for a while. But now I’m just waiting for death” (Alexievich, 1997).

The State's narrative surrounding those helping with the liquidation was that they were national heroes. In April and May of 1986, nobody knew about the firefighters sent to the station who “died horrific deaths of radiation exposure, but prevented an explosion that would’ve made Hiroshima seem tame” (Golinkin, 2016). By referring to young men as heroes, the State did acknowledge their contribution, although slightly covering for all the health issues and suffering that they endured as a result.

However, with this crucial lack of information, “tens of thousands of Soviet citizens filed into Chernobyl to help, considering it their patriotic duty; all were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation with no warning from the government” (Stern, 2013). One of the soldiers mentions: “I didn’t tell my parents I’d been sent to Chernobyl. My brother happened to be reading Izvestia one day and saw my picture. He brought it to my mom. “Look,” he says, “he’s a hero!” My mother started crying” (Alexievich, 1997). For many soldiers there was no other choice but to contribute to the liquidation: “You have to serve the motherland! Serving - that's a big deal. I received: underwear, boots, cap, pants, belt, clothing sack. And off you go!” (Alexievich, 1997).

“The only oddity was, the reviewing stands, where the city authorities stood, were mostly empty” (Golinkin, 2016)

The explosion escalated right before the 1st of May, the International Workers’ Day. The holiday was of great significance in the Communist ideological narrative. The occasion was a yearly celebrated event with large-scale parades in the centers of Soviet cities. In Ukraine, such a parade was going to take place in Kyiv. The authorities of the State discussed whether the event should still happen after the city was exposed to such high levels of radiation. In the end, despite the danger, a few days after the deadly explosion “people rallied to celebrate the International Workers' Day in Kiev, Ukraine, on May 1, 1986. Nobody cancelled the May Day parade in Kiev when thousands of people walked in columns along the streets, with songs, flowers and Soviet leaders portraits, covered with invisible clouds of fatal radiation” (Golinkin, 2016). It was like any other parade on May 1, except for one detail: “the only oddity was, the reviewing stands, where the city authorities stood, were mostly empty” (Golinkin, 2016).

The unawareness and the lack of information, however, continued in the years after the explosion. Many of the former workers of the Power Plant “‘don’t know how they survived’ [which] points to an agonizing lack of knowledge about the actual physical states of those who survived, and where their survival ought to fit within larger schemes of knowledge about the biological effects of Chernobyl - how they were doing, what kind of medical care they needed to go on living, and how long life would last” (Petryna, 2013).

Affected health as a key trauma

One more aspect that has the victims deeply traumatized is that exposure to radiation has long-lasting effects that can influence young and future generations. The wife of the Chernobyl firefighter who stayed with him until his death shared her experience about giving birth to her daughter: “She looked healthy. Arms, legs. But she had cirrhosis of the liver. Her liver had twenty-eight roentgen. Congenital heart disease. Four hours later they told me she was dead” (Alexievich, 1997). After coming back home, one of the soldiers shared: “We came home. I took off all the clothes that I’d worn there and threw them down the trash chute. I gave my cap to my little son. He really wanted it. And he wore it all the time. Two years later they gave him a diagnosis: a tumor in his brain” (Alexievich, 1997).

Figure 4: The Chernobyl Firefighters memorial.

Such an increase in radiation had a massive effect on people’s health. “More than 3.5 million people in Ukraine alone, not to mention many citizens of surrounding countries, are still suffering the effects” (Petryna, 2013). The number of cancer cases, especially among young generations, including children, has increasingly risen after the incident, although the levels were quite low globally before the tragedy (Demidchik, et al, 2007). Some people in Alexievich's book share how their children have suffered from the Chernobyl disaster: “I want to bear witness: my daughter died from Chernobyl. And they want to forget about it” (Alexievich, 1997).

The traumatized voices from Chernobyl

The trauma surrounding the Chernobyl nuclear tragedy has multiple aspects. First of all, many of the victims, when interviewed by Alexievich, admit that the general knowledge about the dangers of the nuclear explosion was massively hidden by the State authorities. People felt vulnerable and helpless in the Soviet machinery, while the radiation was spreading through the European soil and beyond.

Secondly, this lack of awareness cultivated by the Soviet regime's media strategy did not leave any option to victims of the tragedy but to be exposed to the health risks. It was a sacrifice of some men for the safety of many. The firefighters, soldiers, power plant workers, ordinary citizens generally had no idea about what was going to happen to them. While being sent to the exploded station, evacuated from their homes, or by staying to live in the villages nearby, the citizens received only a "half-truth" on the events of those days. Most were completely unaware of what was going to happen to them.

Many of the Chernobyl victims have been suffering serious health issues for years. The cancer rate in the district rose, as well as the rates of other mental- and physical disorders. Thirty years after the disaster, “much about Chernobyl and its aftermath remains clouded in secrecy and conspiracy theories” (Golinkin, 2016). There is no unified measure to accurately describe all the complications experienced by people living in Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, and many more countries that were affected by radiation.

Figure 5: The Chernobyl memorial.

The tragedy of Chernobyl has become a trauma for many generations. Ever since it escalated, many of the sufferers could not even openly discuss it. They were immediately stigmatized as "Chernobyltsy"; they were shunned and sometimes even bullied (Alexievich, 1997). Svetlana Alexievich gave voice to the trauma suffered by these countless victims through her book.

The tragedy of Chernobyl is still very much present in the societies of contemporary Ukraine and Belarus. There is a yearly commemoration of the victims and learning about the nuclear disaster is also a significant part of formal education. Students get taught about the tragedy and its outcomes for the population. The governments help affected citizens. The stories of the victims are also very much alive in the national narratives.

The strong message of Voices from Chernobyl

There are not many ways to express the pain the Chernobyl tragedy caused and its consequences in the world. For many years, the archives of the disaster were sealed in the Soviet Union. However, Svetlana Alexievich has managed to find a way to bring out the truth artistically through her book. Her work is of great value both as a truthful recollection of past events and also as an important message to the world at large. While getting to know the trauma of the interviewees, the readers unavoidably ask themselves, what if the same were to happen again?.

For years, people had been silent about the ways in which Chernobyl had affected them: “radiation poisoning was personal and permanent, made all the more frightening by its mysteriousness” (Stern, 2013). Svetlana Alexievich has managed to give voice to this built-up trauma. The stories of the victims will forever stay on the pages of her book and will be left to future generations who can then make their choices in the use of energy informed by the real voices from Chernobyl.

References

Alexievich, S. (1997). Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster. Picador.

Demidchik, Y. E., Saenko, V. A., & Yamashita, S. (2007). Childhood thyroid cancer in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine after Chernobyl and at present. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia, 51(5), 748-762.

Golinkin, L. (2016). The Lasting Effects of the Post-Chernobyl Parade. Time.

Nuclear Energy Agency. (2002). Chapter IV Dose estimates. OECD.

Petryna, A. (2013). Life Exposed: Biological Citizens After Chernobyl. Princeton University Press.

Stern, M. J. (2013). Did Chernobyl Cause the Soviet Union To Explode? The nuclear theory of the fall of the USSR. Slate.