Eco-terrorism: going in depth on the fur industry 'blueprint'

The topic of eco-terrorism is not very visible in contemporary media. However, radical environmentalist organizations have a long-lasting history, international networks, and strong links to contemporary activism. Operating mostly under the radar, they distribute pamphlets, raise awareness, and work towards expanding their network.

This paper examines the message communicated by the radical environmentalist organization Animal Liberation Front (ALF). The movement is strong and active in 2020. Recently, ALF has published a guidebook to ending the fur industry “The Blueprint: Fur Industry Analysis. Weak Links. Addresses”. The issue collects all the most recent information on the fur industry in the US. This paper focuses on the rhetoric and targeted audience of the piece.

With the growing visibility of sustainability and climate discourse in the media, we need to understand the different historical methods applied to fight for the cause of ecological living. Although eco-terrorism presupposes committing crimes for the sake of its ideology, it became one of the stepping stones for the worrying topics to finally be acknowledged by the public.

Eco-terrorism: liberation or a threat?

Eco-terrorism is a type of activism that branched from the radical environmentalism movement. The term was first coined in the 1960s (Long, 2004). Eco-terrorism is defined by the FBI as: “the use or threatened use of violence of a criminal nature against innocent victims or property by an environmentally-oriented, subnational group for environmental-political reasons, or aimed at an audience beyond the target, often of a symbolic nature” (Jarboe, 2002).

Figure 1: The Animal Liberation Front activists and the rescued animals.

Eco-terrorism was especially popular as a way of resistance to the corporate-driven system which negatively influenced the environment. The eco-terrorist organizations were especially active in the 90s and 00s. Multiple attacks on property were executed as a way to effectively fight for a safe environment before the law does. The FBI charged eco-terrorists with 200 million US dollars in property damage in the years 2003-2008 (Baldwin, 2008). The majority of states in the US have introduced laws aiming to penalize eco-terrorism (Baldwin, 2008). The organizations dealing with eco-terrorism mostly work under the radar and have discrete websites or contacts.

Figure 2: The Animal Liberation Front logo.

The Animal Liberation Front was established in the 1970s and is still active in the field of radical environmentalism. The organization has an international leaderless network. The movement tries to resist animal cruelty. Although the organization positions itself as promoting a non-violent way of climate action (Long, 2014), critics have often labeled them ‘terrorists’.

The philosophy of ALF requires direct action with the activists arguing that animals should not under any circumstances be viewed as property (Regan, 1983). Activists claim that the rescued animals are not ‘stolen’ but ‘liberated’ and the reason for that is that they were never rightfully owned in the first place (Best, 2004).

Eco-terrorism’s Blueprint

The website of ‘Animal Liberation Front-Line’ has recently published an animal abuse resistance handbook directed at those wishing to dismantle the fur industry (see Figure 3). The piece is posted under the headline ‘Out now: new ‘Terrorist’s Handbook,’ Updated for 2020”.

Figure 3: The handbook's cover.

The new version of the action plan starts with a preface to the updated version which sums up the achievements ever since the last document was published in 2009. It is said that “After its release, The Blueprint has a cascading effect -- both direct and speculative”. The older edition provoked a chain of anonymous research, document leaks, and industry tracking. Soon after its publication, the media called The Blueprint “a terrorist handbook” (Young, 2020).

Figure 4: The updated issue of the Blueprint.

The author stresses the need for making a new, updated Blueprint to keep on bringing positive change. The 2020 issue states that the number of new addresses in the fur industry is massive. The document aims at stopping animal abuse. The new Blueprint focuses on the updated strategies of radical action with more detail on the industry vulnerabilities (Young, 2020).

How to Destroy The Fur Industry

The first section starts by stating that the “document is a blueprint to destroying one animal abuse industry in the United States” (Young, 2020). The handbook introduces some of the facts about the industry saying that “The fur industry is not the largest animal abuse industry (or the smallest). It is not even the most measurably cruel” and that there are still worse fates than being born into a fur farm (Young, 2020).

Figure 5: The 'How to Use' part of The Blueprint.

The handbook explains that currently, the fur industry is quite weak. The data for The Blueprint has been collected due to thousands of hours of research (Young, 2020). The documents analyzed in the handbook have been collected in different ways, also with the help of breaking into industrial buildings, infiltration into the field, and other radical steps.

Figure 6: The data collection process described in the handbook.

How to Destroy The Fur Industry elaborates on the previous actions taken by the ALF. The handbook gives intertextual references linking to, for instance, Operation Bite Back Until Today: Fur Farm Data in the 2000s, or the Why Vegan? pamphlet. The Blueprint offers strategies, the newly discovered names, and the upcoming targets.

Figure 7: The statement in the handbook.

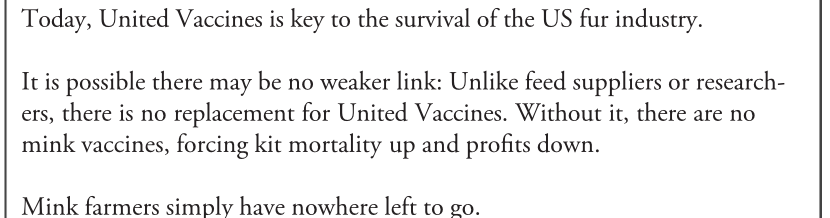

The further sections of the handbook explain that the industry meltdown is possible and that action should be taken now (see Figure 8). The Blueprint describes the weak links of the fur industry that can be targeted by radical activists. Numerous company names are mentioned under the Feed Suppliers, Processing Plants, Fur Industry Research, Aleutian Disease, Melatonin Implants, and Vaccines subsections. The information deals with different links that need to be targeted by the activists to destroy the fur supply chain.

Figure 8: Calls for action in the handbook.

The author further shares his personal story of activism in the research of the industry. The first-person perspective makes the appeal more personal. The story sets an example in line with the ‘if I can do it so can you’ rhetoric.

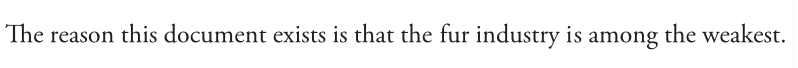

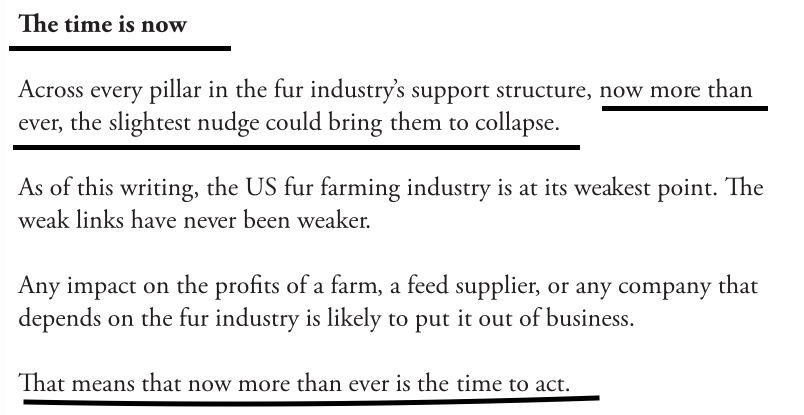

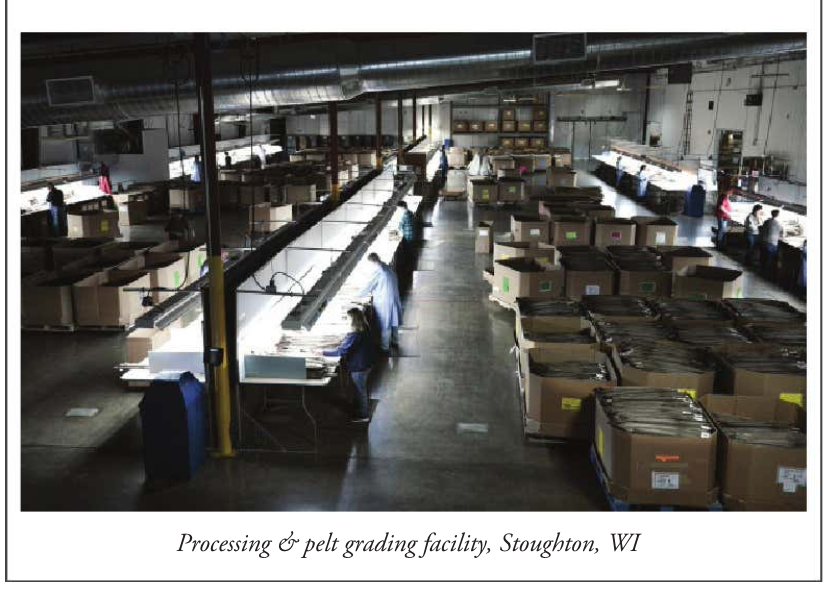

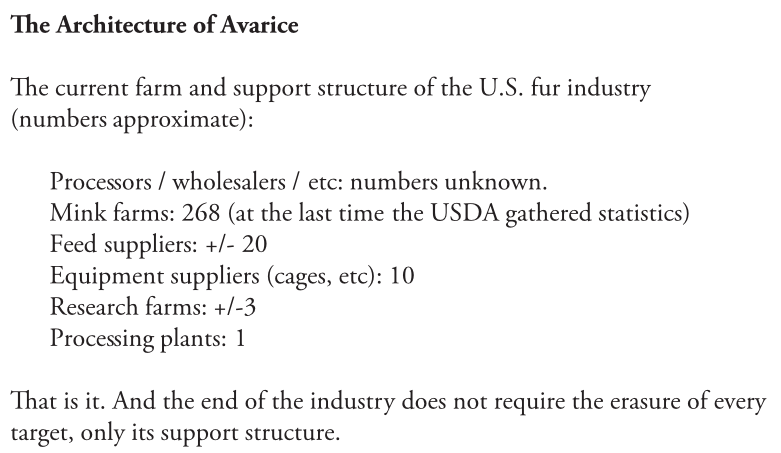

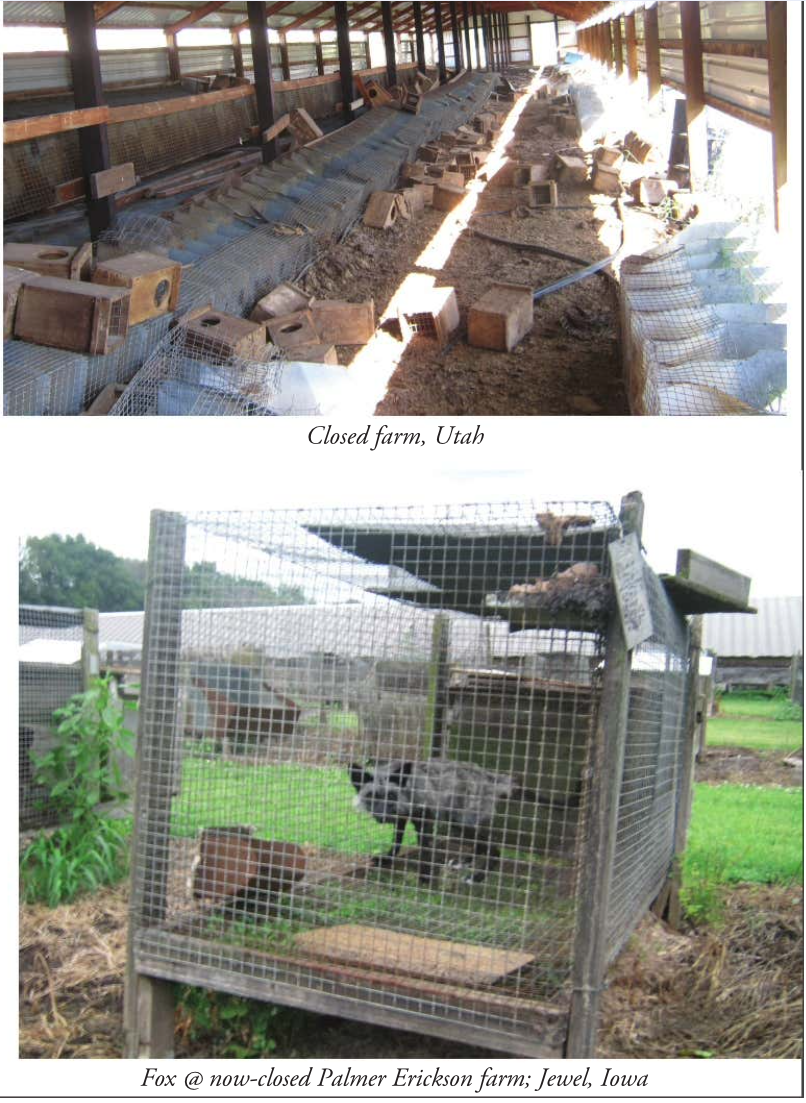

Figure 9: The fur farms pictures in The Blueprint.

The Blueprint goes further by exposing the existing fur farms across the US with their pictures and precise locations (see Figures 9 and 10). The list of addresses goes as far as one hundred pages of the handbook presenting the scale of the problem.

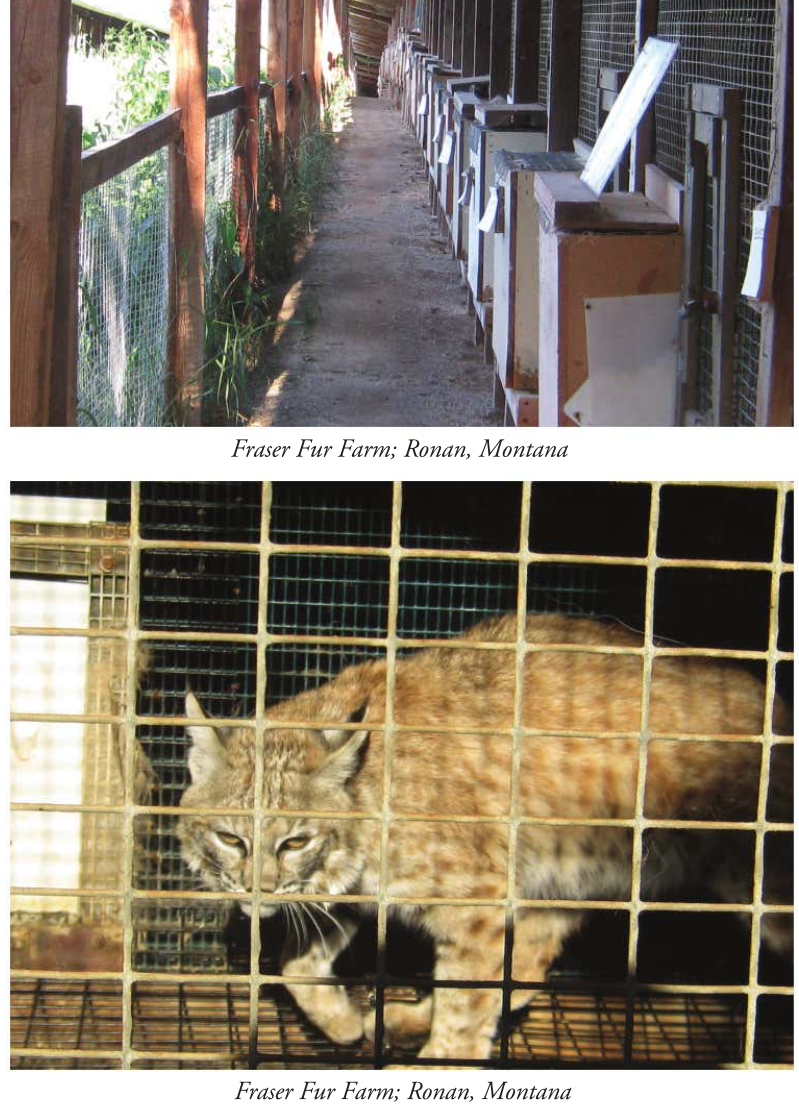

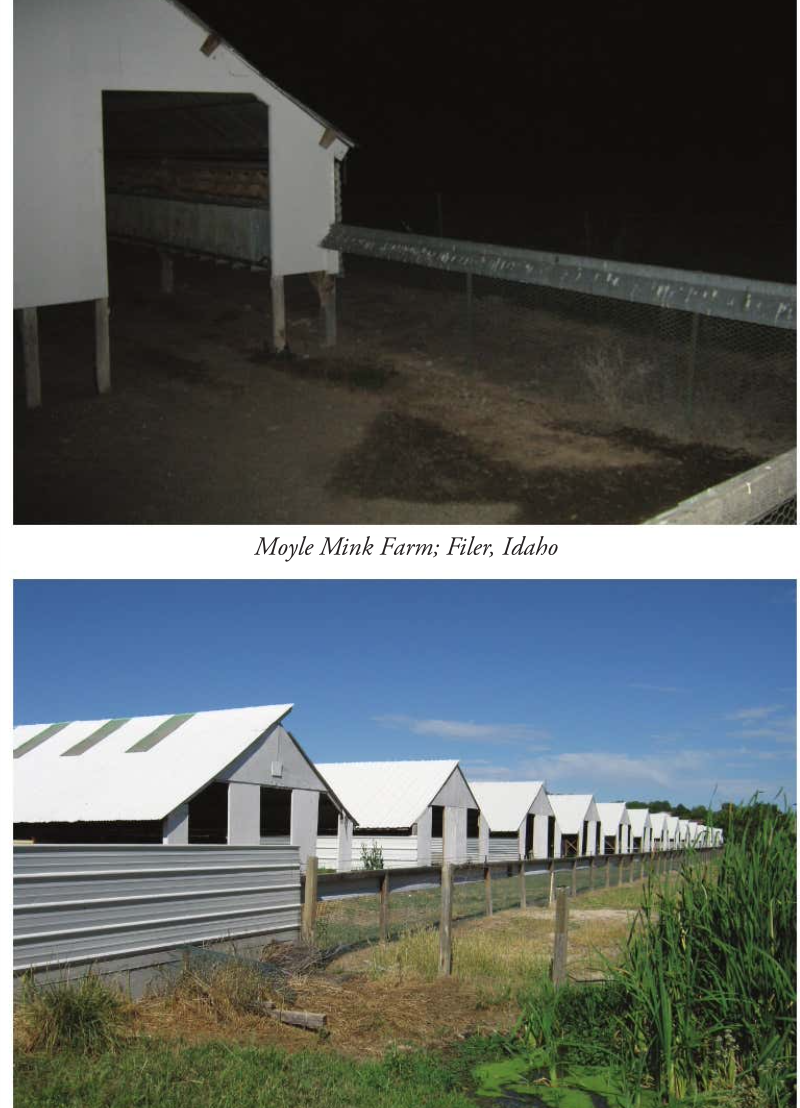

Figure 10: The pictures of fur farms published in The Blueprint.

The final part of The Blueprint presents the addendum list of “closed farm list, small farm list, data sources, fur farm numbers, [and] most wanted list” (Young, 2020). The piece concludes with the recruitment of new fur farm investigators, providing the readers with external links to further research. The Blueprint also promotes the other work by the author ‘Stories and Lessons on Animal Liberation above the Law’ written with a radical tone of voice.

The climate change rhetoric

When it comes to the climate change discussion, a few primary themes tend to emerge in the public sphere (Hoffman, 2011). The first one deals with “the scientific consensus that human behavior is causing a rise in greenhouse gas (GHG) levels, and that these gases are altering the global climate” (Hoffman, 2011). The second one focuses on “the policy consensus that the solutions to this problem lie in technological development and behavior” (Hoffman, 2011). Another view lies on the opposite side of the spectrum and is often called ‘climate skepticism’. In this debate, the direct action perspective gets overlooked.

Figure 11: A picture from the fur farm published in The Blueprint.

Eco-terrorism is not often talked about in the media, however, the movement is still strong both underground and above-ground. Multiple organizations operate around the ideology of radical environmentalism. Contemporary movements like ALF do not want to wait for legal solutions to climate issues that can take years to regulate and they aim for an audience who can potentially have similar intentions.

The Animal Liberation Front-Line website chooses a specific strategy of communication to address the issue. Their rhetoric calls for a problem-based approach. The published handbook has quite a formal nature and it combines the application to research, a personal perspective, and a call for action.

Whom do we blame?

The general social problem addressing climate change is that it does not have a well-defined ‘human face’ (Hoffman, 2011). The issue that “will most drastically impact future rather than present generations” does not have a clear addressee in the media space, unlike “debates over abortion, immigration, gay rights and even the death penalty” (Hoffman, 2011).

Figure 12: Blaming the pharmaceutical company for helping the fur industry in The Blueprint.

Radical environmentalist organizations are quite straightforward in giving a human face to the problem. The ALF handbook publishes the complete lists of the customers and contractors of fur on different levels from vaccines to feed suppliers. The group has clearly defined causes and solutions in line with environmental radicalism rhetoric.

Intertextual links

To bring the message across, the handbook uses intertextuality to link the reader to the other works of ALF. The text becomes hybrid and transcultural which is a desired feature in the ideological battle (Laineste & Voolaid, 2016). The handbook becomes a successful cultural unit that is then globally mediated “to a very wide range of audiences who consume them in different ways” (Laineste & Voolaid, 2016).

Web culture provides low-cost social network environments (Laineste & Voolaid, 2016). The text in the handbook refers to previous works published by the ALF. The Blueprint invites the reader to dig deeper into the works of the organization to take a straightforward approach to solve the issue. The high involvement in the investigation on the topic might invite a certain percentage of the readers to take further steps toward the radicalized action.

Disidentification of climate activism

The identification of a certain type of movement online is done through the usage of “a range of semiotic materials: linguistic, visual, textual and multi-modal” (Leppänen, et al, 2013). The ALF handbook contributes to constructing a certain identity online. The appeal created by The Blueprint is “entwined with [the] simultaneous offline activities” (Leppänen, et al, 2013) of the organization.

Figure 13: Describing "the end of industry" in The Blueprint.

The handbook uses the promoted mediatized terminology of the environmental crisis, however, the rhetoric gets reshaped in a more radical manner motivating the reader to take direct action. The Blueprint uses the semiotic means available to organize the handbook in a way to bring across a convincing message. The document uses a rather official tone of voice and makes the argument stronger by attaching pictures of the farms. The handbook is written formally with clear language and a personal approach. The Blueprint uses the available textual and semiotic means to promote radical activism.

Eco-terrorism and storytelling

One of the tools used to make the handbook more convincing is the personal perspective of the writer. Using references to narratives, stories, and storytelling has become a very common tool in addressing environmental issues (Moezzi, et al, 2017). Personal stories are used to build a strong and trustworthy connection with the audience. They are used to communicate with, influence, and convince the readers (Moezzi, et al, 2017).

Figure 14: Collected data of the closed farms published in The Blueprint.

This strategy is used by the author of The Blueprint, who shares his journey of collecting data on fur firms across the country. Presenting his example, the narrator shows that anyone can take radical action concerning environmental activism. Moreover, the reader is invited to do so by having all the addresses of the firms published in the book.

Conclusions: eco-terrorism and radical action

The message of the radical environmentalist handbook The Blueprint is built to be convincing, formal, and motivating. The issue sums up the efforts made to combat animal exploitation in the past years, links the reader to additional sources of information, presents the personal story, puts the blame on different actors, and discloses the firms’ locations.

The rhetoric of The Blueprint is convincing. The handbook stands in line with ALF’s philosophy of direct action. The Blueprint’s distribution is aimed at recruiting people who are fed up with populism and empty promises of combating environmental issues. The document encourages the readers to take action if they want to see the real change. The handbook is a strong tactical tool in spreading the eco-terrorist rhetoric both underground and above-ground.

The general public tends to ignore the materials published by eco-terrorism movements. The Blueprint and similar documents are never discussed in mainstream media, but they are accessible online. Up until today, they attract new participants and serve as inspiration for radical action for the ever-growing movement.

References

Baldwin, B. (2008). Wade's war. Style Weekly.

Best, S. (2004). Introduction. In Best and Nocella. (eds.) Terrorists or Freedom Fighters?. Lantern Books.

Hoffman, A. J. (2011). The culture and discourse of climate skepticism. SAGE.

Laineste, L., Vooldaid, P. (2016). Laughing across borders: Intertextuality of internet memes. European Journal of Humour Research.

Long, D. (2004). Ecoterrorism. New York: Facts on File.

Moezzi, M., Handa, K. B., Rotmann, S. (2017). Using stories, narratives, and storytelling in energy and climate change research. Energy Research & Social Science. ELSEVIER.

Regan, T. (1983). The Case for Animal Rights. University of California Press.

Jarboe, J. F. (2002). Domestic Terrorism Section Chief, Counterterrorism Division Federal Bureau of Investigation. The Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Young, P. (2020). The Blueprint: Fur Industry Analysis. Weak Links. Addresses.