Elon Musk's SpaceX: How the 'space race' to Mars adopted The Californian Ideology

Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Richard Branson — what do they have in common except for being the Big Tech CEOs? The recent trend among billionaires is to invest in space industries or the so-called ‘space race'. The tech entrepreneurs have put in efforts to privatize the space industry by launching rockets, taking tourist space flights (Guthrie, 2016), and promoting the 21st century as the age when space will become affordable to ordinary citizens.

The current article is going to analyze the discourse surrounding SpaceX and the colonization of Mars project widely promoted by Elon Musk. The piece is going to argue that with the launch of the new space development trajectory of big tech, the project adopted The Californian Ideology (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996) as its rhetorical tradition. The article will analyze materials launched on the Mars inhabitation project to see what it has inherited from the big tech industry rhetoric.

Elon Musk and Californian ideology

Elon Musk as a media personality and his projects such as SpaceX, PayPal, Starlink, Tesla, SolarCity, The Boring Company, Open AI, Neuralink, and Hyperloop are the products of a certain ideological tradition. The world of the big tech industry as we know it got influenced by the paradoxical hybrid of the political left in terms of liberation and political right in what comes to establishing a conservative secluded class and entrepreneurial zeal (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996).

Figure 1: Artistic representation of the future Mars colonizer presented by Elon Musk in 'Making Humans Multi-Planetary Species' (2017).

This complex trajectory has developed under the sauce of technological determinism — the belief that technology determines society, its values, and structure (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). In addition, The Californian Ideology adopted American neoliberalism which promotes individual responsibility in achieving industrial and corporate success.

The result of this multilayered combination is a certain type of rhetorical mindset predominant in the major Silicon Valley-based tech companies throughout the late 20th and the early 21st centuries. The principles developed back in the day are still big tech's "discourse and power" (Blommaert, 2005). The Californian ideology discourse influences the technological corporations and their workers from within. However, since the industry has only been growing throughout the last decades, being a major part of our economies, media highlights, and cultural products, it has also become a significant influencing factor for society as a whole. The newcomer products in the field also rapidly adopt the spirit of the Californian ideology. One of such projects is SpaceX, and more specifically its Mars inhabitation mission.

The Californian Ideology as a term deals with Silicon Valley rather than the larger entity of California. The latter also encompasses more traditional liberal values, rather than just narrow libertarianism, in the American context. For instance, a sympathetic attitude to European-style social organization and an uneasy acceptance of 'racism, poverty and environmental degradation', rather than denying them. That is one of the reasons why Musk moves his company to Texas.

SpaceX’s sci-fi inspiration

SpaceX or Space Exploration Technologies Corp. is a company founded by Elon Musk in 2002. The corporation focuses on manufacturing aerospace technologies and on services and communications of space transportation. For this article, two presentations ‘Making Life Multi-Planetary’ (2018) and ‘Making Humans a Multi-Planetary Species’ (2017) given by SpaceX’s CEO Elon Musk at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC), as well as the company’s website, are going to be analyzed in detail. The materials are predominantly tech-oriented, describing the process of transportation of Mars. They feature vivid artistic illustrations to ease the public imagination of machinery concepts. To a lesser extent, the presentations and the website focus on Musk’s role in the crafting of the Mars civilization, the reasons for the expansion, the characteristics of Mars as a planet, traveling costs, and living conditions for humans.

Figure 2: The mission section of the SpaceX website.

The mission of SpaceX is to take steps to become a spacefaring civilization and to eventually make humanity multi-planetary (SpaceX, 2021). The company’s website, among others, presents a separate ‘Mars & Beyond’ section (see Figure 2). The title ‘Mars and Beyond’ was first launched in an episode of the Disney series and it discusses mankind’s life on different planets, eventually focusing on Mars. The episode brings to life the science fiction novel ‘The War of the Worlds’ of H. G. Wells which deals with the Martian invasion of Earth, and E. R. Burroughs’ ‘Barsoom’ series that focuses on life on Mars (DisneyWiki, 2021). The dream of Mars inhabitation, in line with Californian ideology, takes its inspiration partially from sci-fi novels.

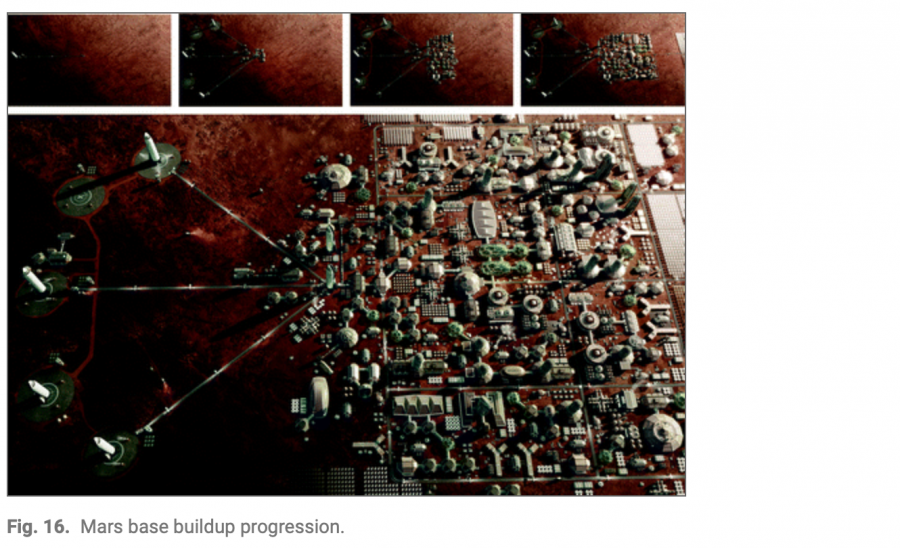

In fiction, life on Mars is often presented as a higher and more technologically developed form of society. Musk’s presentations of the colonization project feature imagery of futuristic-looking devices and strategies to help humans survive on Mars. Briefly, he presents his audience with plans of the creation of a “self-sustaining city—a city that is not merely an outpost but which can become a planet in its own right, allowing us to become a truly multi-planetary species” (Musk, 2017). The ambition is to build a Mars base that starts with one ship “then multiple ships, then we start building out the city and making the city bigger, and even bigger” (Musk, 2018). The presentation also features rich imagery of artistic vision of the Mars buildup progression.

The idealized image of Mars

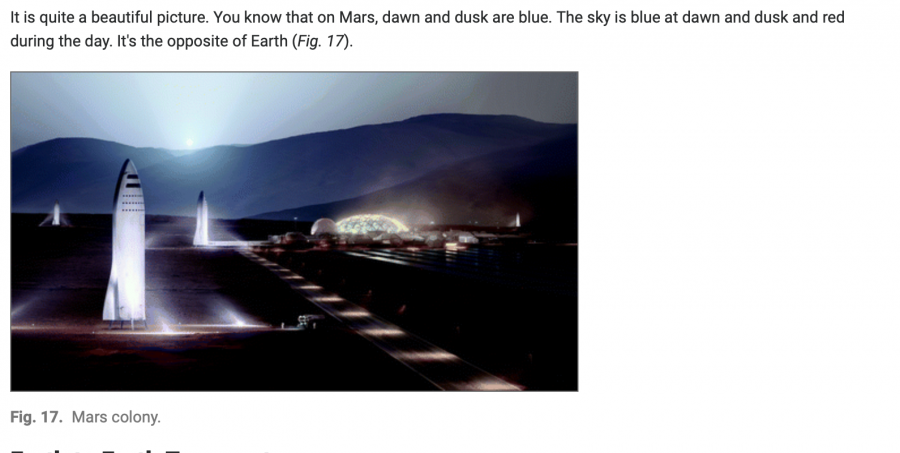

In the rhetoric used by Musk, going to Mars is presented in a pretty romanticized way. For instance, while the presentations are technologically-oriented, the tech entrepreneur talks about the color of the sky on the planet (see Figure 3). ‘Making Life Multi-Planetary’ and the SpaceX mission website both start with his quote: “You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great - and that's what being a spacefaring civilization is all about. It's about believing in the future and thinking that the future will be better than the past. And I can't think of anything more exciting than going out there and being among the stars” (Musk, 2018).

Figure 3: The Mars colony visualization from the presentation 'Making Life Multi-Planetary' (2018).

The romanticized vision of living on Mars is rather simplified. One could argue, we already live among the stars with an undeniably beautiful sky above us. The application of optimistic imagery serves multiple purposes. On one hand, it justifies millions of dollars in investments in the project and attracts more funding. On the other hand, it promotes the space journey idea and gains more social acceptance, especially in the eyes of the like-minded audience of big tech enthusiasts in the best Californian ideology tradition. The view can be put in the framework of cyber libertarianism or the "vision of freedom in which technology in the hands of ordinary people was seen as liberatory, as enabling the formation of do-it-yourself communities free from state and corporate power" (Dahlberg, 2017; Barbrook, 2015; Turner, 2006).

The idealized narrative of Mars inhabitation opens up hopes for an optimistic future. History repeats itself with some of the big tech beliefs in the world “where cars had disappeared, industrial production was ecologically viable, sexual relationships were egalitarian and daily life was lived in community groups” (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). Making this possible in practice means adopting the hippie-inspired view which was of big influence in the Californian rhetoric. Namely, working with nature and making life on Mars livable for humans, while hoping that technological progress will help turn “libertarian principles into social fact” on a new planet (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996).

Figure 4: The visualization of "Over time terraforming Mars and making it really a nice place to be" (Musk, 2018).

The idealized rhetoric creates an appeal of the virtual place where everyone is technologically advanced and free, living without fear of censorship (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996), and working together for common future goals. In fact, it is good to stay critical and question whether this trajectory would take place in practice. After all, such factors as the adoption of neoliberalism within the Californian Ideology became one of the causes of not realizing its utopistic image.

Mars and technological determinism

The representations of the Mars inhabitation process are focused on the technological aspects of space travel and settlement. The measurement of advances of the human race and their readiness to become multi-planetary species is being put on technology. This view lies at the origin of the Californian ideology and consequently leaves a mark on the space discourse. The rhetoric surrounding Mars inhabitation is centered around technological determinism. Described in the words of Hannah Arendt (1958): “[t]ools and instruments are so intensely worldly objects that we can classify whole civilizations using them as criteria”.

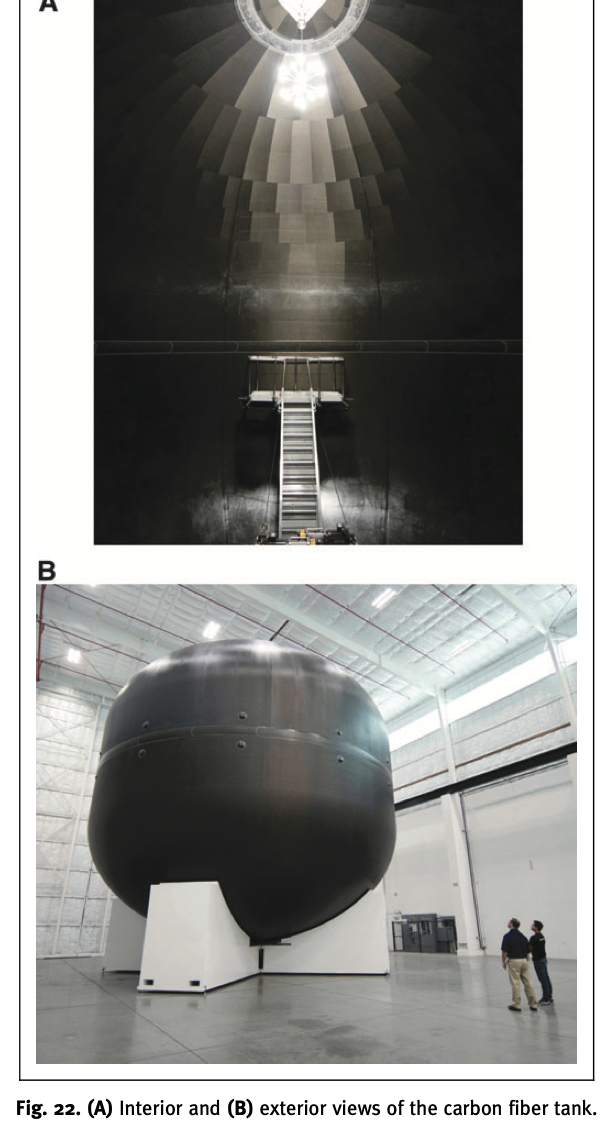

Figure 5: The carbon fiber tank presented in the 'Making Humans a Multi-Planetary Species' presentation (2017).

Technological focus in the center of the idea of building a new civilization reinforces the belief that machinery will “empower the individual, enhance personal freedom, and radically reduce the power of the nation-state” (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). Such a media representation of technology, however, can be problematic since it implies how seemingly liberating technologies are turning into the “machines of dominance” with the outlined trajectory of future development (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996).

Elon Musk’s neoliberal space leadership

The presentation ‘Making Humans a Multi-Planetary Species’ (2017) contains the following statement: “by talking about the SpaceX Mars architecture, I want to make Mars seem possible—make it seem as though it is something that we can do in our lifetime. There really is a way that anyone could go if they wanted to”. Another presentation a year later also makes a claim on the leading role of Musk: “We started off with just a few people who really didn't know how to make rockets. And the reason that I ended up being the chief engineer or chief designer, was not because I wanted to, it's because I couldn't hire anyone. Nobody good would join, I ended up being that by default” (Musk, 2018).

The self-centered approach and the personal initiative of Musk in the presentations demonstrate the DIY culture as an example of successful involvement in tech (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). This refers to the vital component of American tech entrepreneurship — individual initiative. This approach is in line with the neoliberal ideal of a person who takes responsibility into his own hands and works hard towards a successful future which has been adopted by the big tech industry (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). In addition, Musk’s presentations demonstrate how the introduction of the media, computing, and telecommunication technologies separate the workforce from direct involvement in the production of the factories and offices sustaining the tech firm, visibly simplifying the manufacturing process (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996).

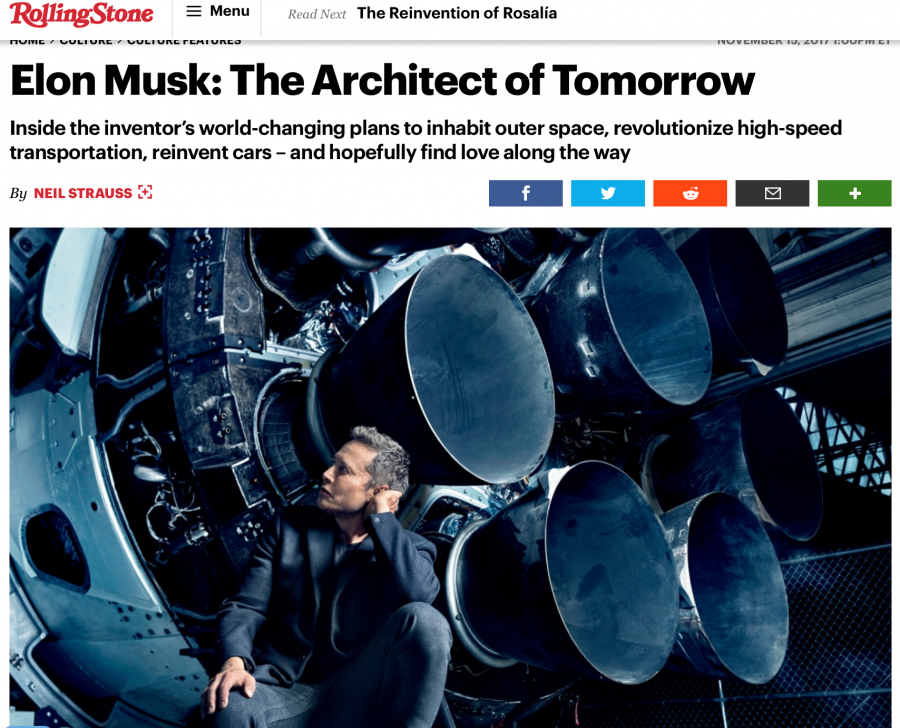

Figure 6: The Rolling Stone interview header calling Musk 'The Architect of Tomorrow'.

Elon Musk takes a key position as the representative and the media ambassador of SpaceX and its multi-planetary mission. Therefore, looking at his media persona means taking a glimpse at the ambassador of Mars inhabitation idea. When it comes to Elon Musk describing his plans he is often called ‘the visionary’, ‘the architect’, and ‘the inventor’ of our collective future (see Figure 6). The billionaire's plans involve ideas that will need decades for realization. His media images reinforce the single inventor appeal as they often feature futuristic motives capturing Musk alone in front of rockets or gigantic machinery. Often, when the inventions of his companies are referred to, they address the tech boy and not the team of engineers and programmers working behind the scenes.

Figure 7: Some of the most widely used SpaceX promotion images featuring Musk alone in front of the company's technological inventions.

The tendency of getting most credits for the work done by the joint cooperation of thousands of people employed by Musk’s companies is an example of the Californian ideology. The tech boy is the embodiment of the elite of the so-called ‘virtual class’, or the “the techno-intelligentsia of cognitive scientists, engineers, computer scientists, video-game developers, and all the other communications specialists” (Kroker & Weinstein, 1994). The collective labor and the intellectual capacities of this virtual class are used to develop Musk companies’ products. The many employees of tech firms become a collective of skilled workers organized through fixed-term contracts by their managers (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996) to keep releasing new technologies they rarely get acknowledged for.

Mars inhabitation and post-humanism

Musk states that if humankind will stay on Earth forever, there will eventually be some extinction point: “I do not have an immediate doomsday prophecy, but eventually, history suggests, there will be some doomsday event” (Musk, 2017). As a solution, he proposes becoming a “space-bearing civilization and a multi-planetary species” (Musk, 2017). Continuing life on Mars as multi-planetary species is yet another form of virtual immortality chased by the ‘virtual class’ (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996).

The creation of the Mars colony can be perceived as the emergence of a new discursive era of post-humanism. With the presumable conditions of living on Mars, humans would develop strong technological dependency. The post-humanism discourse emerges from the blend of advancing AI with medical science, and sci-fi fantasies of wetware — abandoning the human element in IT architecture (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). This rhetoric operates in the line of perfecting the mind, body, and spirit as a manifestation of the big tech ‘virtual class’ social privilege in relation to their biotechnological developments (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). Post-humanism is yet another pillar of the Californian ideology embedded in Mars inhabitation discourse.

Social class and segregation

Talking about Mars inhabitation leads to the escapist desire into the hyper-real as one of the aspects of technological self-obsession which will most likely deepen social segregation (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). Musk simplifies the divide by stating: “We just need to change the populations because currently we have seven billion people on Earth and none on Mars” (Musk, 2017).

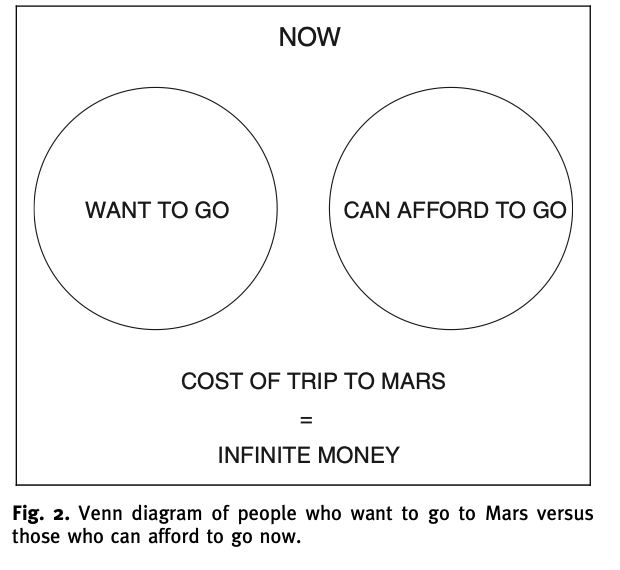

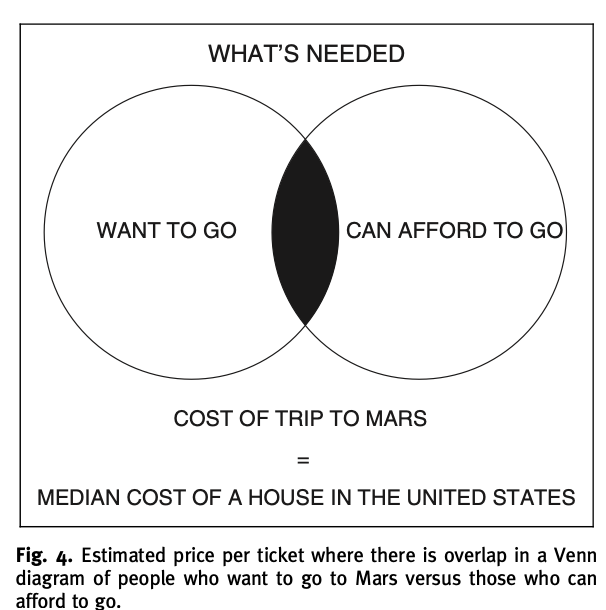

In the presentation, Musk mentions the prices of Mars travel for ordinary people. He states that currently, a ticket would cost $10 billion (see Figure 8), however, the goal would be to drop the price to $200,000. Musk is convinced that “a relatively small number of people from Earth would want to go, but enough would want to go who could afford it to happen” (Musk, 2017). For others, the billionaire advises getting sponsorship or saving up “given that Mars would have a labor shortage for a long time” (Musk, 2017). What it shows is that a limited amount of people who could pay astonishing prices to move to Mars would do it to sustain the same labor system currently existing on Earth.

Figure 8: The current state of Mars ticket costs, 'Making Humans a Multi-Planetary Species' (2017).

In addition, according to Musk (2017): “The threshold for a self-sustaining city on Mars or a civilization would be a million people. If you can only go every 2 years and if you have 100 people per ship, that is 10,000 trips. Therefore, at least 100 people per trip is the right order of magnitude”. The high travel prices and a limited amount of people allowed to travel make a very inegalitarian Mars colonization impression. The Californian ideology is in itself rather discriminatory, inheriting the features of the West Coast life, such as racism, poverty, and environmental degradation (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996), and so is the space travel plan at the current stage.

Do we leave the society as it is and let it expand to Mars, with all the existent problems that we could not solve on Earth, or is there something more utopic coming our way?

In line with the Californian ideology, the inhabitation of Mars is often embraced as “an optimistic and emancipatory form of technological determinism” (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). However, the social polarization of the project is overlooked. Despite the radical rhetoric, the Californian ideology has been nothing but pessimistic about fundamental social change (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). So is the recent Mars colonization project launched by the wealthy tech persona who does not articulate the moral fundamentals of the new type of civilization. This begs the question: do we leave the society as it is and let it expand to Mars, with all the existent problems that we could not solve on Earth, or is there something more utopic coming our way?

Figure 9: The estimated future costs of the Mars journey.

What the observers are presented within the Mars colonization project as presented by Elon Musk, is that it is very ‘optimistic and emancipatory’ on the surface. However, digging deeper and applying a critical lens of ideological power relations, represents a “simultaneously a deeply pessimistic and repressive vision of the future” (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). The ethical questions of Mars’ settlement are not taken into account. The fact that we use the term ‘colonization’ in relation to Mars inhabitation links the words to the problematic ideological context. Therefore, more questions follow up, for instance, who regulates the selection process of who will stay on Earth, and who will join the Mars journey? How will social power structures continue functioning with two (co-dependent) planets? Will there be a distinction between the first and latter colonizers of Mars and their subsequent generations? Will the ‘slave-like robotic labor’ (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996) keep driving the progress on a new planet?

Another issue of Californian ideology being spread to a different planet via the means of the SpaceX project leader is that many people still believe that it is the ultimate way to go forward to the future as human species. However, this is not a set-in-stone doctrine, but rather a historically shaped collection of a particular mix of technological and socio-economic choices (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). After all, the Californian ideology is the most visible developmental trajectory we have experienced in the technological sector. It does not mean, however, that we have to take it for granted without trying to challenge it as a society.

The future of the Californian ideology on Mars

The Californian ideology has infected big tech companies. With the expansion of the industry towards Mars inhabitation, it is only natural that we see some of the key characteristics of the Californian ideology applied to the discourse of the contemporary space race.

The revolutionary ideas of Mars inhabitation have entered our society on many levels, in mass culture products, and even governmental fundings. Arguably, as a society, we can still take agency in the shaping of technological development on Earth and beyond. However, this responsibility should not be put on every one of us who is not necessarily related to the tech field, but to those at the core working as the architects of change. According to Barbrook & Cameron, 1996: “As pioneers of the new, the digital artisans need to reconnect themselves with the theory and practice of productive art”. Contemporary tech projects give a lot of room for the adoption of new creative strategies by taking into account society’s issues and ethics.

The Mars colonization opens up a new era for Californian ideology. The rhetoric surrounding becoming a multi-planetary species sells a promise of an optimistic utopia where everyone “will be both hip and rich” (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). Just as with the rise of big tech in the late 20th century, this vision of the future is enthusiastically embraced “by computer nerds, slacker students, innovative capitalists, social activists, trendy academics, futurist bureaucrats and opportunistic politicians across the USA” (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996).

The Californian ideology has infected big tech companies

In a way, Mars inhabitation combines the two distinct features of Californian ideology. Namely, both movements started as a combination of “political struggle with cultural rebellion” (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996). The idea of Mars colonization can be seen as a sign of despair and frustration with the Earth’s political life of humankind. Moving to another planet has been a fantasy surrounding cultural products for centuries. Inhabiting Mars is symbolic of having a fresh start and taking agency of the new political life, a ‘fresh start’ for the humans. However, it is also a sci-fi dream coming true with Elon Musk being a leader of change.

The rhetoric circulating around the space talk in the case of Elon Musk and SpaceX features a lot of traits of Californian ideology, neoliberalism, and technological determinism. One might argue that this ideologically-shaped view of Mars inhabitation can have multiple implications, such as investing in space travel instead of the Earth improvement, for instance. Part of the Utopian thinking is that it presents our current problems as not solvable with more conventional means. On top of that, the SpaceX project discourse also legitimates a more consuming lifestyle on Earth under the promotion of the idea that doomsday is inevitable anyways.

References

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition.

Barbrook, R. (2015). The owl of Minerva flies at dusk: From dot-com capitalism to cybernetic communism. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Institute of Network Cultures.

Barbrook, R., Cameron, A. (1996). The Californian Ideology. Science as Culture 6(1):44-72.

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A Critical Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Dahlberg, L. (2017). Cyberlibertarianism. Communication. Oxford Research Encyclopedias.

DisneyWiki. (2021). Mars and Beyond.

Guthrie, J., Branson, R., Hawking, S. (2016). How to Make a Spaceship: A Band of Private Spaceflight, an Epic Race, and the Birth of Private Spaceflight. Penguin Press.

Musk, E. (2017). Making Humans a Multi-Planetary Species. New Space, Vol. 5, No. 2. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Publishers.

Musk, E. (2018). Making Life Multi-Planetary. New Space, Vol. 6, No. 1. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Publishers.

SpaceX. (2021). Mission.

Turner, F. (2006). From counterculture to cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.