#YoVotoMM: Mauricio Macri, bots and dirty campaigning in Argentina

Bots, votes and political discourse

It must have looked great on paper: right on the verge of the election silence, a political declaration of loyalty would lead Twitter’s global trending topics (TT): #YoVotoMM (“I vote for MM”). And not just in Argentina; the whole world would take a stand for the current president, Mauricio Macri, and support his re-election.

This article has also been translated in Spanish

Mauricio Macri and #YoVotoMM

To achieve the trending of the #YoVotoMM hashtag, the president and his campaign team called for a Twitterstorm, a massive Twitter event set for August 8th at 19:00, when his supporters were supposed to tweet the selected hashtag.

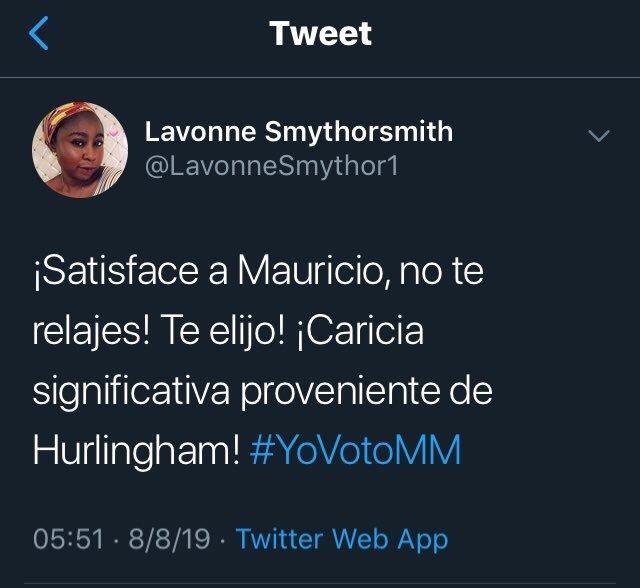

And then came the surprise: a user called Lavonne Smythorsmith tweeted: “Satisfy Mauricio, do not relax! I choose you! Significant caresses coming from Hurlingham! #YoVotoMM” (Figure 1).

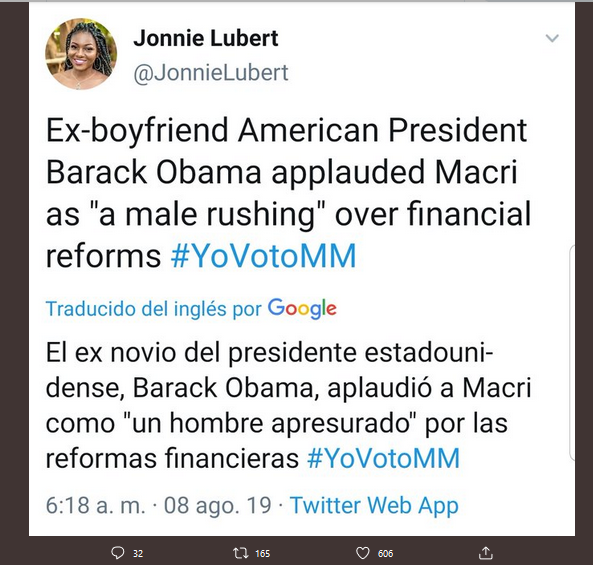

In Spanish, English and French, weird messages began to be retweeted, such as: “Ex boyfriend American President Barack Obama applauded Macri as a ‘male rushing’ over financial reforms. #YoVotoMM” (Figure 2).

A user, @malerey_, traced back the bots’ tweets to their sources: “¡Por favor, Mauricio!” (“Please, Mauricio!”) became “¡Satisface a Mauricio!” (“Satisfy Mauricio,” or “Give satisfaction” to Mauricio); “¡Abrazo fuerte desde Hurlingham!” (“A big hug from Hurlingham”) became “caricias significativas desde Hurlingham” (“significant caresses from Hurlingham”), etc.

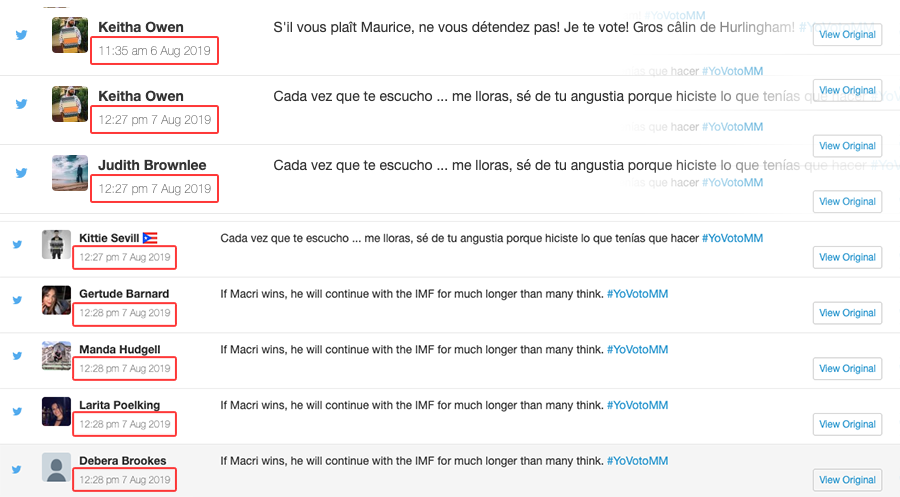

Semantically incoherent, argumentatively contradictory, pragmatically inadequate and in many cases, positively ungrammatical, these tweets came from accounts with little or no followers, identified with unlikely names such as “Lavonne Smythorsmith”, “Keitha Owen” or “Janet Fizhugh.” They had no profile descriptions, and their pictures were inconsistent with their messages, especially in the case of Shawnna Atwell, who posed next to the logo of the opposition party (Figure 3).

Their names, as noted by @kwinnyk, were created using a random name generator script segmenting over a real names database. Therefore “Smyth or Smith” became “Smythorsmith,” “Keith A. Owen” became “Keitha Owen”, “Janet Fiz, Hugh...” became “Janet Fitzhugh,” and so on.

Also, messages were created using an old script which kept Twitter’s old 180 characters limitation, a second rate automatic translator and a dictionary of synonyms which generated variations of actual tweets. The source of these messages were old tweets by Macri supporters and trolls, and news from popular newspapers, many of which were ideologically and politically close to Macri’s government.

The messages were unmistakably generated by bots, tweeting the hashtag #YoVotoMM. And they seemed to be a catastrophic fail.

As the platform deletes messages which repeat exactly the same text, the script which generated the messages performed grammatical transformations and used synonyms to generate similar but different messages. (By the way, this is the very definition of the “discursive formation” concept developed by Michel Pêcheux: a space of paraphrase where every new utterance is, basically, semantically redundant with respect to the others).

In short: they were unmistakably generated by bots, tweeting the hashtag #YoVotoMM. And they seemed to be a catastrophic fail.

Bot demographics

Who created those bots? Are they a product of the ruling party, which succeeded in creating a TT, but failed in making it coherent? Or was it an insidious device created by the opposition to mock the #YoVotoMM campaign? Data scientists and communicators offered proof of both hypotheses.

On the one hand, Luciano Galup (@lgalup), a big data journalist, and @TuQmano, a data scientist, analyzed the composition of the hashtag using the Standard Twitter APIs. They concluded that 1.8% of the total participating accounts were responsible for 33% of the total tweets using #YoVotoMM. Even more: 65% of the tweets were generated by only 10% of the accounts that tweeted.

This behavior, however, can not be directly attributed to the action of bots. As a digital communication advisor told me, there are a few hundred supporters which simply retweet any positive message using the hashtag, and they are undistinguishable from trolls, either paid or voluntary ones. In the same analysis, they stated that 30% of the accounts which tweeted the hashtag do not have any profile description; this is a usually more accurate indicator that they are probably bots or trolls. Although they did not identify the total number of accounts that were undeniably bots, from their point of view the whole affaire was a bot campaign which went wrong.

On the other hand, Guillermo Vagni (@GuillermoVagni), Director of Políticos en redes (@BocaDeRedes), analyzed how many of the #YoVotoMM tweets had been unmistakably generated by bots, i.e., how many of them belonged to the “significant caresses” type. In his report, there were 161 accounts involved (1% of the total participation). There were 1908 “badly written” tweets, 168 of which used the expression “Satisface a Mauricio” ("Satisfy Mauricio"). His conclusion: the bots did not significantly help to make the hashtag a global TT, but they did help to install #SatisfaceAMauricio as a TT in Argentina. Vagni’s research team detected that these bots had been created and had had a short activity, one or two messages, two days before the Twitterstorm (Figure 4).

If they were malfunctioning, they should have been detected then. Finally, there is the question of saliency: how did prominent Twitter political influencers find such unknown bots if they had not been alerted about their existence? Assuming that Macri’s campaign team is highly professional, and that there was enough time to monitor and stop the campaign if any mistake had been detected, Vagni concludes that the whole episode was a dirty campaign strategy performed by some opposition group.

Bots and votes

We could attempt a linguistic analysis of these bot-generated tweets, in the traditional fashion of discourse analysis. “Satisface a Mauricio” can be understood either as a mistake which still reproduced the form of a command, thus retaining an asymmetrical relationship between speakers. It can also be seen as a parody, an erotic exaggeration of the emotional content of Macri’s campaign. It is impossible to decide between both interpretations without actually knowing who created these bots and with which aim. Although discourse analysis has traditionally avoided explicit considerations of the political effect of political discourse, arguing that there is no direct relationship between production and reception, algorithmic populism places the distribution and uptake of political discourse at its core.

If it was a government-led campaign that went wrong, it shows that these messages had no communicative value but rather a purely algorithmic value.

Distribution was the main communicative act of this bot campaign: if it was a government-led campaign that went wrong, it shows that these messages had no communicative value but rather a purely algorithmic value, in order to fuel the hashtag #YoVotoMM. If it was a dirty opposition campaign act, it was designed to be retweeted and mocked by opposition influencers, who "exposed" an alleged fakeness of Macri's popularity online. In the latter case, bots also were designed to fuel a hashtag, #SatisfaceAMauricio. The hashtag is, in both cases, political discourse of distribution and reception; what matters is not the content, or who utters it, but how it ranks in an algorithmic scale.

Regardless of whether they were pro-government bots which “went crazy” or opposition bots aimed to mock Macri’s campaign, the whole episode touched a very sensitive fiber of Macri’s discursive ethos, as he called for a vote "without arguments or explanations", based on big data, online activism and social media, even celebrating the #YoVotoMM trending topic as a sure index of political popularity.

Yet, there is a limit to algorithmic populism. Surveys (either traditional or big data) pictured a scenario favorable for Macri, some of them even predicting a victory by one or two points. However, the cruel social and economic crisis in Argentina, fueled by financial capitalism – which has its own algorithms and bots – inclined the electorate to vote for the main opposition candidate, Alberto Fernández, who won the PASO elections by a landslide margin of 15%.

Although endangered, democracies still need votes, much more than bots.