The Transcontinental: Benign sousveillance across Europe's other spaces

The Transcontinental is an unsupported, free route cycling race across the old continent. Unsupported is ultracycling lingo for inevitable emotional breakdown. On a goat track. In Albania. At dusk. No outside support is allowed. Instead, the rules stipulate that the race must be ridden 'in the spirit of self-reliance and equal opportunity'. Free routing means that there's no fixed route to the finish. Only control points and parcours: mandatory sections on variable surfaces stubbornly mislabeled as 'gravel'. I had the pleasure of competing in the 9th edition of the Transcontinental Race (#TCRNo9), along with 340 other thrill-seeking masochists from 47 countries. A sweaty pilgrimage of attrition from the cobbled streets of Geraardsbergen in Belgium to the smooth pavement of Thessaloniki's waterfront promenade along the Aegean Sea (Figure 1). Over the course of 14 days, 5 hours and 15 minutes, I covered 3.558 kilometers and amassed 45.200 meters of elevation across 12 countries and 4 currencies. Numbers tell poor stories so let me try to make a finer point about what it's like to navigate benign surveillance technologies and fiercely territorial packs of street dogs on a don't-try-this-at-home diet of fizzy drinks, salty snacks and refined sugar.

Fig. 1 Transcontinental No9 race map

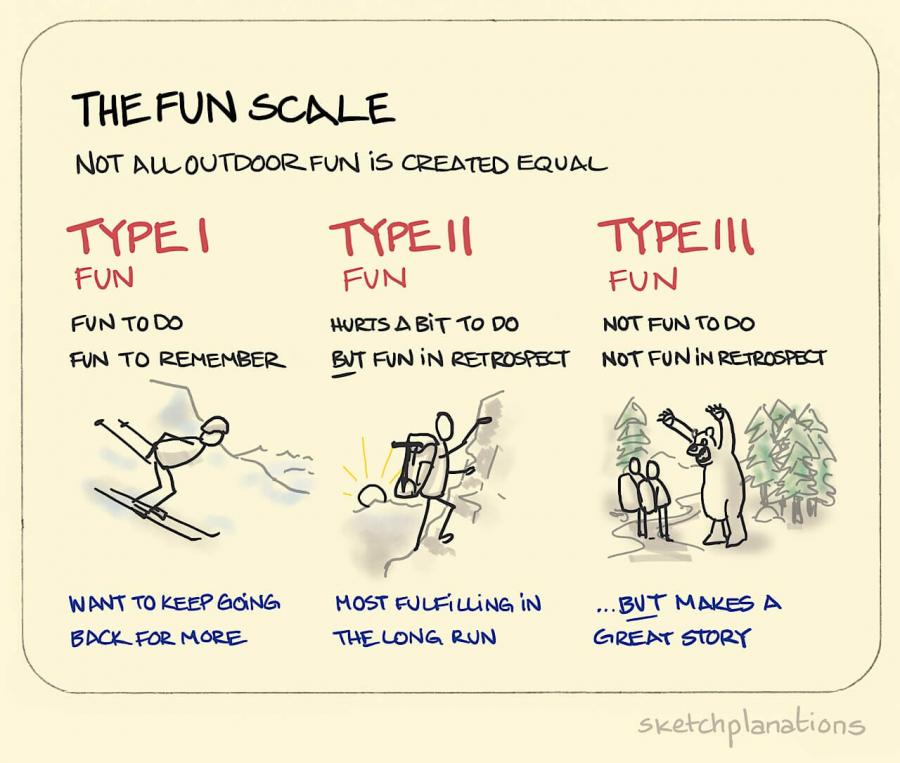

The allure of ultracycling lies in a blend of simplicity, adventure, and community. Ultracycling offers a chance to break away from everyday civilian life, bond with complete strangers over a plate of leftover ice cream cake, and roam avidly above the sea of fog -- case in point: Piva canyon, Montenegro. In essence, ultracycling is a contemporary form of romanticism : a two-wheeled celebration of nature, freedom and isolation. Romanticism is what makes the sport so addictive. And soul-cleansing. The warm, supportive community culture comes a close second. For veteran racer Adrian O'Sullivan (personal communication), ultracycling is about "digging deep and escaping the rat race. It's the closest you can get to living like an animal. All you really have to think about is where you're going to eat, drink and sleep... That's base living. It changes you; allows you to experience deep spiritual feelings and emotions." Granted, climbing Alpine passes in the rain with nerve damage in your hands on 3 hours of sleep is not very romantic (just ask TCRNo9Cap337 Sarah Ruggins after summiting St. Gotthard Pass) but the overall experience is and goes from raw to rosy. It's called Type 2 fun.

There's another dimension to ultracycling that piques my interest here. A dimension that speaks to digital culture, social space and mobility. Here goes. Ultracycling throws into relief the prosaics of machine vision in heterotopian spaces of hedonism and minimalism. Big words for long days in the saddle. Let's unpack them.

Machine vision prosaics

Machine vision refers to advanced technologies of visual automation; how computers understand what they are taught to see. Think of pattern recognition, augmented reality and other forms of artificial sight (Rettberg et al. 2022). The prosaics of digital media examine "how digital media feed into, reflect, and shape other kinds of social practices, like economic exchange, financial markets, and religious worship" (Coleman 2010: 488). My point is not that ultracycling is determined by digital media, but rather organized around it. Cycling across a continent against the clock obviously involves a sustained physical effort, but doing so without digital technologies such as route planning apps and GPS bike computers is hard to imagine. Let alone pull off. Analog ultracycling with paper maps and vintage sausage helmets may very well become a trend one day, as may virtual ultracycling on indoor trainers, but until that day comes, ultracycling implies metrics, screens, and platforms.

Speaking of machine vision, once riders were informed that their application had been successful, they were offered a three-month premium komoot membership. Komoot is a route-planning and navigation app with features such as multi-day tour planners, sport-specific maps and dynamic weather forecasts. These forms of machine vision allow riders to make informed routing decisions to navigate the various control points and parcours. Here's a satellite map of parcours 2, a mandatory 45km section across the Julian Alps in Slovenia and Austria. As soon as I approached the parcours, I relied on Komoot's voice navigation on my phone in addition to my GPS bike computer to follow the exact track and avoid time penalties.

satellite map of TCRNo9 parcourse 2

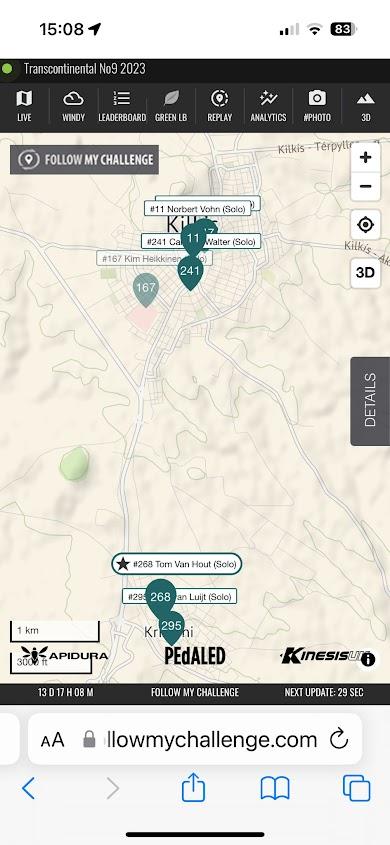

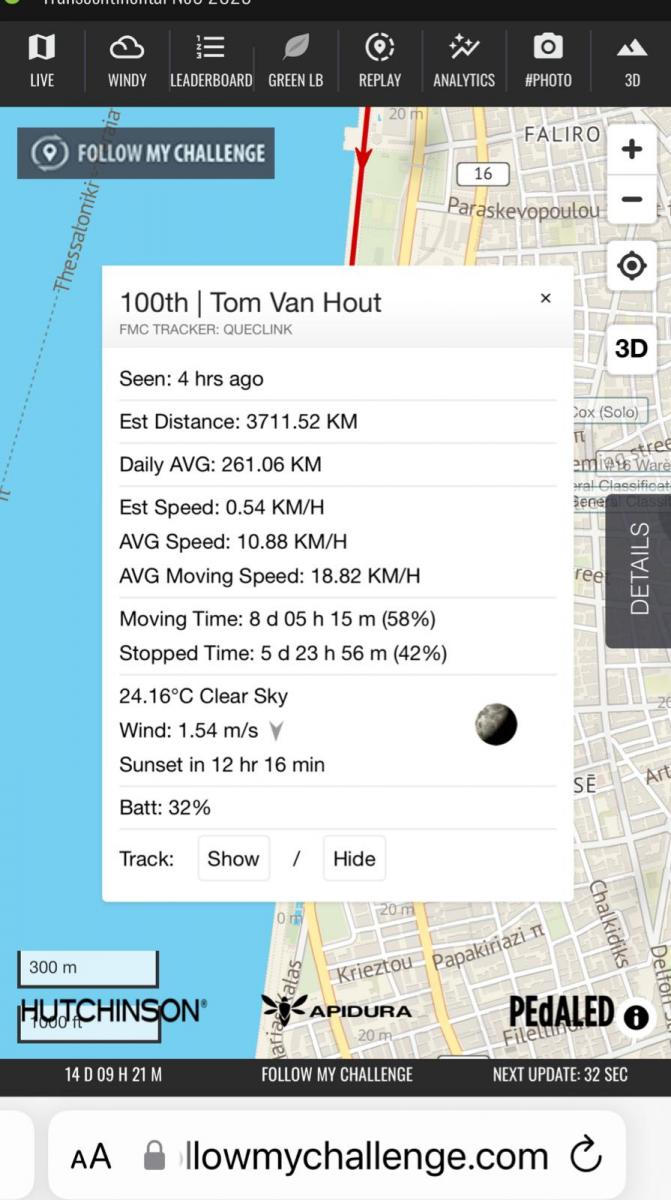

During the race, all riders were expected to self-quantify their movements and whereabouts using mandatory GPS trackers. The Follow My Challenge satellite trackers boast an accuracy of up to 2.5 metres (yikes), last four to six days on a single charge, and are designed to function in temperatures ranging from -20 to +55 degrees Celsius. These pocket-sized monitoring devices track rider progress and visualize their movements in the form of dots on a map (fig. 2) and numbers on screens (fig. 3), This in turn allows race organizers, riders and spectators to engage in dotwatching, a type of benign sousveillance (watching from below or social surveillance) that has come to define the datafied consumption of ultraracing.

Fig. 2 FMC dot TRCNo9

Fig. 3 FMC rider stats

Curiously, being dotwatched invites soiveillance (watching the self). We know from research on self-tracking technology that the digital knowledge we create through automated data comes with assumptions about normality and agency (Crawford et al. 2015). Am I making enough progress? Should I push harder? Is it okay to rest now? How far ahead/behind is rider X and Y? Such questions inevitably lead to firing up a web browser and checking the FMC race map. Repeat race winner Christoph Strasser even used the website to track down the tracker he lost while climbing a sandy section on the finish parcours. Put differently, GPS trackers read and write riders on a map. It renders them visible and legible (Jones 2017). Moreover, since you cannot see who is watching the dots, you start watching yourself. For instance, in supermarkets, the dot tends to move in circles. After a while, I left my tracker on the bike when entering a supermarket to avoid text messages inquiring what I was up to.

Heterotopian hedonism and minimalism

Route planning and dotwatching underscore the data intensive, surveillant nature of ultracycling. Such forms of machine vision - along with the datafied behaviors they invite and constrain - go hand in hand with the lived experience of ultracycling: the rollercoaster of highs, lows, indifference, elation, fear, joy, anger and resentment. Here it's helpful to quote fellow racer and professional photographer Conan Thai: "The profundity of personal revelations is always contradicted by the banality of our physical movements and needs." I would argue that Thai's contradiction between thoughts and actions is heightened by the spatial and sensory sensation of alterity and otherness. It was Michel Foucault who coined the term heterotopia to describe how some spaces stand out as different, alien or contradictory. A heteropia is neither a utopia (a perfect place) nor a dystopia (a bad place). It's a world within worlds. One that tends to make us acutely aware of our surroundings. Classic examples include prisons, bath houses, graveyards, brothels, and submarines.

Riding the Transcontinental Race can be described in heterotopian terms as relentlessly hedonistic and materially minimalistic. It is a hedonism of delayed gratification and small comforts such as a shower or a hot meal. It's about minimizing pain and discomfort (while somehow not cursing the race organizers) and maximizing the pleasure of seeing the world by bike (unless you're aiming for a podium spot). At the same time, ultracycling is an exercise in minimalism. Bikepacking strips our material lives of excess stuff. You take the bare essentials because you have to haul everything you do strap to your bike up and down mountain passes and roads. Kit choice is vital. Sunscreen, chamois cream and power banks are too. Everything else is optional or can be purchased en route. Hedonism and minimalism play out in unexpected, contradictory settings and encounters. Here's a tale from the field for illustration.

Day 10. A hike-a-bike uphill gravel shortcut is cut short by unannounced road works. I'm deep in Albania's rugged heartland and headed towards parcours 3, a 45km stretch of unpaved remoteness. The wildlife (turtles, sheep, donkeys, cows and horses) outnumbers the wild living locals. The summer heat is wild. My brain is fried. My legs feel like I've been cycling since the fall of the Berlin Wall. As I start the unrelenting pink granite rock ascent from Burrel to Peshkopi, I remind myself why this event looked like a good idea back in December - silly me. Four hours of slow progress later do I realize that I won't make it off the mountain before nightfall. The descent is technical. Large rocks, ruts, roots and sharp turns rule out high speeds on 30mm road tires.

Portuguese profanities emerge from the valley. Marcos, a Brazilian ultracycling veteran has been attacked by a swarm of wasps. I stay with him until he calms down. When we finally reach the end of the parcours, I see lights. Salvation! I make a right and cycle down a ramp that leads to what I assume is an upscale wedding venue. The place looks brand new but is deserted. A carpenter emerges from a room and informs us that we can spend the night if we pay 50 euro cash. I frisk myself but find only Bosnian coins and one 20 euro bill. Politely, we insist. "Wait, I give you boss." He hands me a Nokia cell phone. The boss listens to our story and casually tells us that we can have a room for the night. For free. Elated we ask if there's a restaurant on site. "Yes, by the water".

Marcos and I charge our devices in the room and head downstairs. The restaurant is empty and so we play the waiting game. The open-air kitchen beckons. Starving, we heed its call. We chop fresh veggies, cook pasta and feast on what is the probably the best tasting draft beer in the world. Self-supported racing and feeding in a heterotopian kitchen.

TCRNo9Cap268 rider card (commissioned sketch art)

Conclusion

Ultracycling is an increasingly popular sport that brings together a community of "down-to-earth folks with a slightly unhinged thirst for adventure and a deep, shared love of the wild spaces we have the privilege of moving through" (Doyle 2023). Drawing on my own experience of racing TCRNo9, I characterized unsupported, free route long-distance bike races as digitally mediated feats of endurance across surveillant, remote landscapes. I described how the sousveillant effect of being dotwatched invites soiveillant behavior: self-monitoring of rider progress and that of riders around you on the tracking app. Another effect is the 'othering' of space, heightened by a relentness hedonism of delayed gratification, minimalistic mobility and unexpected Albanian hospitality. Cheers!

References

Coleman, E. G. (2010). Ethnographic Approaches to Digital Media. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39(1), 487-505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104945

Crawford, K., Lingel, J., & Karppi, T. (2015). Our metrics, ourselves: A hundred years of self-tracking from the weight scale to the wrist wearable device. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4-5), 479-496. doi: 10.1177/1367549415584857

Doyle, T. (2023, April 4) Ultra Distance Plastic Resistance: An Open Pledge for the Ultra Community. The Radavist.

Jones, R. H. (2017). Surveillant landscapes. Linguistic Landscape, 3(2), 149-186. doi: 10.1075/ll.3.2.03jon

Rettberg, J. W., Kronman, L., Solberg, R., Gunderson, M., Bjørklund, S. M., Stokkedal, L. H., . . . Markham, A. (2022). Representations of machine vision technologies in artworks, games and narratives: A dataset. Data in Brief, 42, 108319. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2022.108319