Protestscapes and the art of protesting in Romania

In this article I will analyse the semiotics of the anti-corruption demonstrations in Romania (January - February 2017). I will introduce the concept of "protestscape" to analyse these local protest from a globale perspective. I define protestscapes as a language of mobility that employs rich semiotic resources within the context of protest.

What is a protescape?

In this article I introduce the concept of "protestscapes" as a language of mobility that employs rich semiotic resources within the context of protest. In doing so I focus on the anti-corruption demonstrations in Romania (January - February 2017).The term "protestscape" draws on Appadurai's notion of the dimensions of global cultural flows. In his book, Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization, Appadurai puts forward a framework for discussing the five dimensions of global cultural flows (ethnoscapes, ideoscapes, mediascapes, technoscapes, financescapes).

These are "collective", "imaginary", and "transnational" landscapes (Appadurai, 1996, p. 31). By adding the common suffix "-scape", the landscape becomes "fluid" and "irregular”. In addition, he indicates that “these are not understood in terms of objectively given relations that look the same from every angle of vision but, rather, that they are deeply perspectival constructs inflected by the historical, linguistic and political situatedness of different sorts of actors” (Appadurai, 1996, p. 33).

The contemporary globalized world is best understood as a "world of flows" comprised of "objects in motions", such as “ideas and ideologies, people and goods, images and messages, technologies and techniques” (Appadurai, 2000, p. 5). In this regard "protestscape" can be understood as landscapes resulting from creative and perspectival interactions between "objects in motions" in both the online (digital activism, instant sharing of updates, using hashtags , creating memes, posting and sharing pictures from protests, creating online events, and so on) as well as offline environment (demonstration marches, protest placards, people wearing badges or clothing with messages, and so on).

To describe “the protestscape" I analyse the linguistic landscape, that is the visible “bits of written language” in the public space, (Blommaert & Maly, 2016: 1) and the semiotic landscape to approach more complex, multimodal signs. The images in this article were retrieved from various sources in the online environment. All pictures were taken during the anti-corruption demonstrations in January and February 2017. I discuss the images by looking at how they present themselves (the type of material used, the choice of colours, the theme of message, etc.) their indexicality (what the sign points to in the context where it is produced), and their intertextuality (their relation to other texts).

The anti-corruption protests in Romania were peaceful, creative, and - even without a formal leader - very well organized.

Altogether, the messages disseminated in online and offline environments employed light-hearted humour, satirical remarks, creativity, witty slogans, playfulness, self-irony, and entailed references to various movies, and books.Some were retorts to controversial statements made by politicians or public confessions, while others directly addressed fellow protesters.

The Romanian political context

In order to make sense of the images presented in this article I will start by explaining the social and political context that lead to these protests.

In December 2016 the Social-Democrats won the legislative elections held in Romania. This was a result of a low youth voter turnout and a higher voter turnout in rural areas of Romania that historically favour the Social Democratic Party (PSD). No more than a month after they took office, the PSD party, led by Liviu Dragnea, passed a decree to pardon certain convicted persons for acts of corruption such as bribery and trading of influence. With this law, PSD was trying to put to rest a growing anxiety amongst public officials due to the effectiveness of the anti-corruption institution (DNA).

The people reacted promptly to the new legislation, threatening large-scale demonstrations. After two weeks of protesters flooding the streets and the media with their concerns and demands, the ruling cabinet annulled the decree. Even though protesters' demands were met, (during January-February and previous demonstrations as well) there is still a high degree of distrust and general dissatisfaction with the current political class. This is largely caused by staggering inequality caused by corruption encountered at every level of society.

Dr.Octopus as the villain

In the Romanian “protestscape” Liviu Dragnea was one of the central figures mocked by protesters. The ruthless jokes and ironic references hint at his involvement with various illicit activities, for some of which he has been proven guilty. He received a suspended two years jail sentence and at his influence within the party.

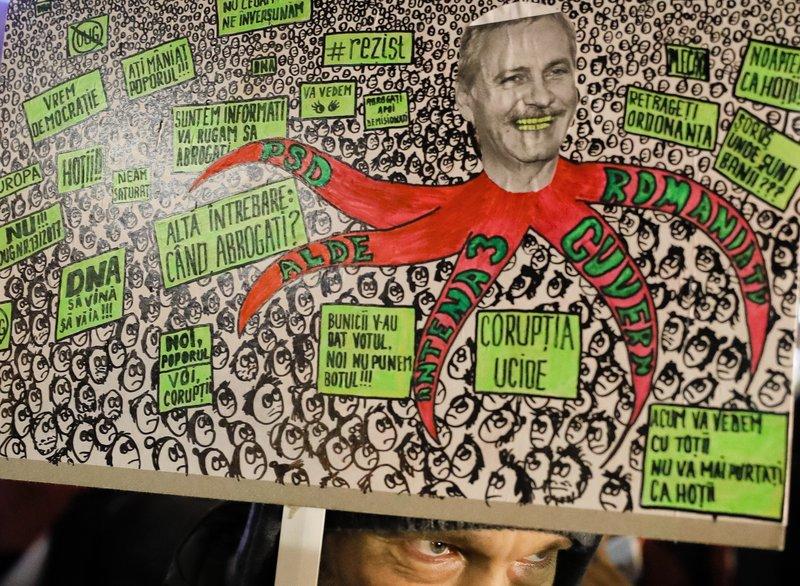

Figure 1

In Figure 1 Liviu Dragnea is painted as an octopus with red tentacles that read (from left to right): “PSD” (the ruling party),”ALDE” (the second ruling party), “Antena 3” (a private TV channel that is owned by a former public official and convict), “Government”, and “Romania TV” (a state-owed channel strongly associated with the ruling party). We can “read” the protest sign as Dragnea’s influence within Romanian society and politics.

The octopus with Liviu Dragnea’s face as its body came on top of the protesters' placards that read messages in support of democracy and against Liviu Dragnea: “We want democracy”, “Our grandparents voted for you, we don’t buy it”, “Thieves”, “Like thieves, in the night” “You angered the people” “Corruption kills” "We- the people, You- the corrupt" .

“The protestcape” is intertwined with other landscapes and is created by the movement of and interactions between protesters – the “makers” of “protestscape”.

This protest sign breaks away from the rest by assuming a position of “summarizing” the multitude of protest signs that appeared in public spaces during the demonstrations, and which cascaded though the "mediascape" (Appadurai, 1996). Therefore, “the protestcape” is intertwined with other landscapes and is created by the movement of and interactions between protesters – the “makers” of “protestscape”. Overall, this is an artful protest sign which appears to be made out of mixed media: cardboard, markers, and paper. We could look at this protest sign as a piece of art in itself. It is an original painting with a strong underlying message.

Figure 2

Figure 2 is another sign that portrays Dragnea with tentacles, this time as the comic character Dr. Octopus – a scientist who evolved into a supernatural being after a scientific experiment went wrong and left him with two extra pairs of limbs, which he controls with his mind. Filled with bitterness, resentment and a willingness to punish everyone around him, Dr. Octopus became a target for the pop culture superhero Spider-man. Dr. Octopus was defeated many times but he always somehow managed to survive. Dr. Octopus is a character that proves difficult to completely annihilate. In terms of indexicality, the inability to "kill" the villain Dr. Dragnea could stand for the failure to replace the crooked political system that emerged in the aftermath of the fall of communism in Romania, and which is currently backed by a corrupt political class.

What we see is Dr. Octopus – a globally recognized character - that receives a local feature the face of Liviu Dragnea and becomes Dr. Dragnea.

This multimodal sign contains various references that come together in this picture. Varis & Bloammaert (2015, p. 33) give a definition of memes that best reflects the process of “reading” a meme. In their opinion, “Memes – often multimodal signs in which images and texts are combined – would typically enable intense resemiotization as well, in that original signs are altered in various ways, generically germane – a kind of “substrate” recognisability would be maintained – but situationally adjusted and altered so as to produce very different communicative effects”.

What we see is that Dr. Octopus - a globally recognized character - receives a local feature in the face of Liviu Dragnea, becoming Dr. Dragnea. This is also true for the text. The sign presents significant intertextuality, as we can recognize Trump’s campaign slogan but rephrased topoint at local corruption. Nevertheless, Trump was not the first to come up with this slogan. An earlier form of the catchphrase “Make America great again” was used by Ronald Reagan during his run for presidency.

This skillfully made image comes together nicely and depicts in a cheerfully coloured picture the supervillain status of Dragnea, pointing to how corruption makes its way into the Romanian justice system. By means of text it hints at another leader whose policies are questionable In contrast to Figure 1 where the sign discussed was homemade, this one is ready-made, easily downloadable from the Internet, and free of charge on the website Art of Protest. It even comes with clear Do It Yourself instructions on how to print and assemble the pieces. The sign is made out of plastic which makes it durable and sturdy, rain proof and snow proof. Thus, it is a reusable protest sign and non-biodegradable.

The website Art of Protest provides a wide selection of protest signs to choose from. This is a grass-root project that gathers chants during demonstrations and transforms them into artworks. They invite protesters to "Download. Print. Protest". As is the case with most digital-age protests,preparation is done online (whether we speak of digital activism, organising events on social media, etc.) while demonstrations happen in the streets and squares. Similar websites emerged during demonstrations in order to store in digital form the messages called out on the streets, slogans, and placard images.

Batman to the rescue!

Figure 3

Another pop culture references points to Batman (Figure 3) – a comic character, who unlike other superheroes did not get his super powers by accident (such as Spider-man) or unusual personal situations (like Superman), but by perfecting his human skills. The protesters used large high lumen projectors to project the bat-signal on the façades and roofs of buildings as a call for Batman’s help. In Gotham City, summoning Batman was intended to intimidate the villains. In Bucharest, projecting the bat-signal on a building is a humorous approach to dealing with local corruption.

As opposed to graffiti, an out-lawed practice, images projected on buildings have the same implications but without the legal consequences.

However, this playful visual statement is particularly interesting as it is temporally emplaced on a building. The image secures its purpose of conveying meaning before it disappears or changes into something else. While displayed, the image has an impact on the public space, at least for its high visibility and large-scale format. As Philip Seargeant and Frank Monaghan wrote in Street protest and the creative spectacle, “in the context of visual representation size matters.”

Moreover, a statement placed on a building in an urban area, put together by a group of “unauthorized people”, alludes to graffiti. J. Ferrell observed that “in a remarkable variety of world settings, kids (and others) employ particular forms of graffiti as a means of resisting particular constellations of legal, political and religious authority” (Ferrell, 1995, p.77). Thus, graffiti have entered the global flows as a form of resistance. Graffitidisrupts order and challenges authority. But, as opposed to graffiti, which is out-lawed in many countries including Romania, the images projected on buildings have the same implications as graffiti, but without the legal consequences. This is to say, light disappears as quickly as it appears.

“Chuck Norris Help”

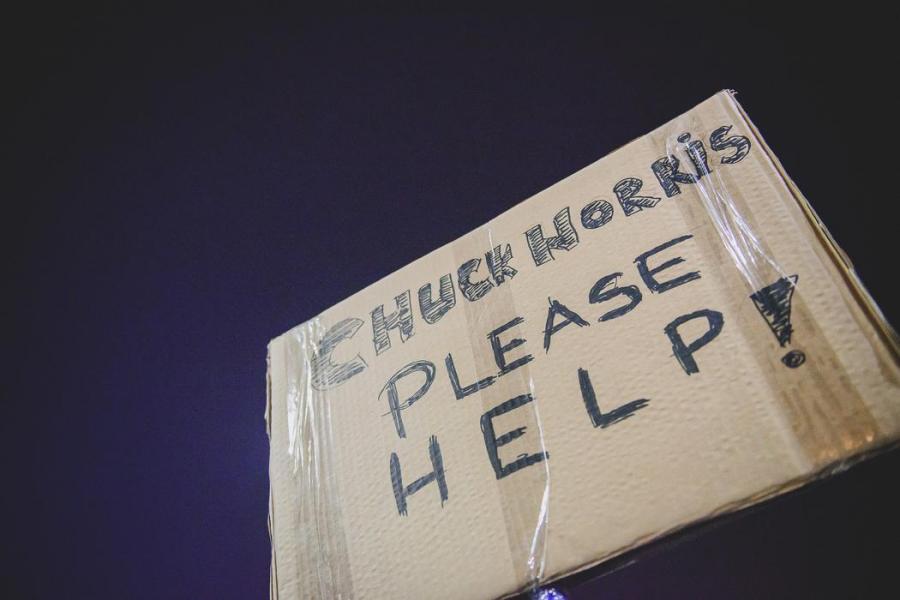

Figure 4

Figure 4 is a protest placard created with traditional means: black marker on a piece of cardboard. It is the message that caught people's attention. It reads "Chuck Norris Please Help!" and it is yet another (satirical) reference to Romanians' counting on super-human forces to save the day. Chuck Norris facts (@chuck_facts) have entered global flows through the “mediascape”. They take Chuck Norris, the actor and martial arts fighter, and exaggerate his strength, abilities and physical condition, conveying super-human capabilities. These "facts" humorously describe Chuck Norris' overwhelming power, overpowering masculinity and his enhanced virility. In other words, Chuck Norris, encompasses all the great qualities one needs to take over the world, or rather that the world is already his to do with as he pleases because “there is no theory of evolution, just a list of creatures Chuck Norris allows to live”.

If there is anyone able to single-handedly save the country from corrupt politicians, Romanians can pin their faith on Chuck Norris.

The @chuck_facts Twitter account has fueled fans with Chuck Norris facts and has over 270,000 followers as ofNovember 2017. Also the hashtag #ChuckNorris allows people to collectively contribute to this large data base of Chuck Norris jokes and references.

The Local vigilante

Figure 5

During demonstrations the use of props extended beyond projectors and protest signs to theatrical costumes. Figure 5 symbolizes a righteous local historical character, Vlad the Impaler. The historical ruler of Wallachia is known for his hatred of those who disobey the law as well as his passion for torture devices. Vlad the Impaler is both a historical and a fictional character, as many horror stories of blood sucking vampires are attached to him. He was the basis for the character Dracula in Bram Stoker’s famous book, and has since been source of inspiration for movies.

Without waiting for a superhero to come save them, the people become the superheros themselves.

The sign he is holding reads “Miss me?”, and invites Romanians to think “What if…” The message is handwritten on a home-made cardboard sign. The character appears to be standing on a pedestal, and theatrical lighting gives a dramatic effect. Overall, this is a humorous performance. The protester has assumed the identity of a (local) vigilante by wearing a 15th century costume. Indeed, the theatrical costume is worn as a mockery, yet this protest technique, like the previous examples, has multiple layers of interpretation.

When citizens' rights are threatened, they have a responsibility to protect them. Civilians index this by taking on the identities of heroes and vigilantes.The people become the superheroes instead of waiting for someone to save them.. Large demonstrations may provide a means for that.

Eventually, Romanians realized they had to save themselves

Figure 6

As is the case of Figure 2, the protest placard in Figure 6 also appears to be made out of a flexible, strong and durable material that may have been meant for reuse. It is attached to two wooden sticks, which makes it easier to be carried around during marches by one or two people. The carefully designed placard and its placement in a public space references road signs.

Imparting a message in the public space usually takes an official form. Signs are therefore institutional objects overseen by some sort of authority and are used to convey information of general interest: they give information, announce prohibition, or give direction (Blommaert & Maly, 2016: 3). In this context the protest placard in Figure 6 can be seen as an act of rebellion against local authorities that regulate signs, in other words sanitize the public space. A protester placing a home-made sign is a form of resistance to authority. With this, the public space itself is re-signified as a space belonging not to authorities, but to the people that occupy the streets and squares.

Meaning conveyed by signs in the public space may depend on colour, form, location. The simplest example of such a sign is a traffic or road sign. We can recognize the shape (diamond shape) and colour scheme (yellow) as that of road signs. The text "(...) under construction" has borrowed terminology from public traffic signs. In terms of indexcality, the message “Miracles under construction” may reveal optimism coming from a strong and unexpected solidarity among Romanians in the face of corruption. It may also point at a hope for a more unified country where common civic disobedience brings people together

The protestscape of Romania

Protesters wield a variety of instruments to transmit their concerns and demands. In addition to numerous protest placards of diverse shapes and sizes, protesters also made use of rock-parody concerts, flash-mobs, (improvised) musical instruments, speeches, marches, stickers posted around the cities, messages imprinted on their clothes, badges, flashlights, puppets on sticks, video projections on buildings, laser projectors, costumes, masks, and many more.

The visual representation of the protest in the online environment included numerous pictures taken during protests, sharing of updates, platforms for recording the timeline of anti-corruption demonstrations, and collective contributions of texts and images under various hashtags. Other genuinely creative ways of mocking the current political class, for instance, included online games that imitate older video games such as Space Invaders ( PSD Invaders) and Pac-Man (Teleorpacman), customized to address the Romanian context.

Light-hearted humour, satire and self-irony largely prevailed in framing “the protestscape” of Romania. In many instances it offered a pressure relief valve, most especially when politicians’ statements and actions were acts of defiance of the people. As a consequence, they distinguished “us” – the people from “them” – the corrupt, and enabled protesters to construct “the protestscape” on a feeling of “togetherness”. On top of concerns and demands, messages disseminated in the offline and online environment contained retorts to contentious statements made by politicians, public confessions and messages directly addressing fellow protesters. This large repertoire of action resonated with a diverse group of people. Protesters came from all walks of life. In the square there were university professors, teachers, students, children with parents, professionals, the unemployed, artists, pensioners, and many others. They interrupted their daily routines, put on hold other activities and with utmost diligence and persistence attended daily demonstrations.

References

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Appadurai, Arjun. Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination. Public Culture, vol. 12, no.1 (Winter 2001): pp. 1-19.

Blommaert, Jan & Maly, Ico. Ethnographic linguistic analysis and social change: A case study. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, no. 100 (June 2014), pp. 1-27.

Blommaert, Jan, and Varis, Piia. Conviviality and collectives on social media: virality, memes and new social structures. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, no. 108 (September 2014): pp. 1-21.

Ferrell, Jeff. Urban Graffiti: Crime, Control and Resistance. Youth & Society, vol. 27, 1 (September 1995): pp. 73- 92.

Kaveney, Roz. Superheroes! Capes and crusaders in comics and films. (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2008), ProQuest Ebook Central.

Marin, Ioana. Parlamentare 2016: tinerii chiulesc, rezultatul e decis de segmentul 45-64 de ani. PressOne, December 21, 2016.

Marinas, Radu-Sorin, and Ilie, Luiza. Romanians rally in biggest anti-corruption protest in decades. Reuters, January 31, 2017.