The algorithmic populism of Matteo Salvini

Salvini and his Lega Nord have become influencial political actors, not only in Italy, but on a European scale. This article analyses the communication strategy of the Italian populist leader.

Salvini and The Lega Nord

The decline of political ideologies and citizens' identification with parliamentary parties has lead to the legitimacy of 'populism' as a means of expressing the citizens' in advanced democracies.

In many ways, Populism is an inaccurate term whose meaning is linked to the historical-political context. In the United States it has a positive connotation, in Latin America it has had militaristic connections, but in Europe it has always had a nationalistic meaning. In European countries populism mobilizes the idea of nation as identity, and makes an enemy of pluralism. Once the people have achieved political inclusion, populism is an attempt to capture and unify them through the use of certain words or supposed atavistic values.

In Italy the movement that specifically incorporates these characteristics is the Lega Nord and its leader, Matteo Salvini. The Lega Nord (in English: Northern League), whose complete name is Lega Nord per l'Indipendenza della Padania (Northern League for the Independence of Padania), is a right-wing party in Italy.

The Lega Nord advocates the transformation of Italy into a federal state, fiscal federalism, and greater regional autonomy, especially for Northern regions. At times, the party has long proposed to make Padania (The area surrounding the Po Valley in Northern Italy) an independent nation, and secede from the Italian state. However, with Salvini the message has changed. A new slogan, “Italians first!”, has replaced the old secessionist battle cry. The party has embraced Italian nationalism and emphasized Euroscepticism, anti-elitism, and opposition to immigration. This is all while forming an alliance with right-wing populist parties at the European level such as France's National Front, the Netherlands' Party for Freedom, and the Freedom Party of Austria.

Further, Salvini established a sister party in southern Italy named “Us with Salvini.” For the 2018 general election he restyled the party's symbol and name, dropping the word "Nord" and introducing "Salvini Premier". After the elections, the party formed the current Italian government called the “Populist coalition” as an equal partner with the other major populist party, the Five Star Movement. This party has a similar populist appeal but a message that is less nationalistic in tone.

Even though these changes have been criticized, under Salvini the League has reached its highest popularity, both in the North and the rest of Italy. In northern regions the party still has a strong autonomist outlook, especially in Veneto where Venetian nationalism is stronger than ever.

Why is Salvini a populist?

Within the field of populism studies, populism can mean very different things. However in referring to the most recent literature, it has become a euphemism for radical ideological positions and is used a synonym for racism, authoritarianism, and nationalism. From this point of view, Salvini can be considered a populist.

In his book What is populism?, Jan-Werner Müller defines populism as "a particular moralistic imagination of politics, a way of perceiving the political world that sets a morally pure and fully unified—but, I shall argue, ultimately fictional—people against elites who are deemed corrupt or in some other way morally inferior. (…) In addition to being anti-elitist, populists are always anti-pluralist: populists claim that they, and only they, represent the people” (Müller, 2016: 19-20).

The Lega Nord seems to correspond to Müller's definition of populism. In fact, Salvini’s party is not only anti-elitist, but also anti-democratic, anti-pluralist, and moralistic. In common parlance, populism functions as an euphemism for far right or even extreme right positions. Their ideological position is now normalized as 'the voice of the people'.

The label populism helps Salvini in giving authority to his claim to be the exclusive representant of the people. This communicative frame, where the leader speaks with the voice of the people, is at the heart of populism (Maly, 2018). Indeed, there can be no populism without someone speaking in the name of the people as a whole. Not only do journalists, other politicians, and media label Salvini a populist, but Salvini has described himself as a populist in several speeches: “I am and I will always be a populist, because who listens to the people and does his job and his duty”? or even, “When they call me populist, for me is a compliment. If by calling me a populist or “LePenist” they think to offend me, they do me a favor instead.”

If we analyze “populism as a mediatized communicative and discursive relation” (Maly, 2018), and study the communicative process, we see that media and communication play a fundamental role for Salvini both in the process of becoming a populist and in the strategy of gaining consensus among the population. So, changes in the media field have affected how populism is constructed. Specifically the development of new digital media has brought two main kinds of revolution:

First, the Internet and other digital technologies have facilitated the rise of a “society of self-disclosure” (Thomson, 2005) in which it is common for political leaders and other individuals to share some aspects of their self or their personal life.

On the other hand, the specific technology of the Internet and the possibility of collecting and elaborating a potentially endless number of data gave birth to so-called “algorithmic populism”. It is a populism not only constructed in relation to journalists, politicians and academics, but also in relation to citizens, activists, computational agencies and algorithmic actors.

Algorithmic populism is a populism that is embedded in the Internet. It uses social media to not only speak to the electorate directly, but also uses data collection to create specific targets and adapt its message to them. This is the kind of populism Salvini developed. He mobilizes an anti-elite discourse, he creates the needs of the people and claims to represent them, he collaborates with different actors as journalists, politicians and academics and most importantly, he has a strong and complex digital media infrastructure through which to distribute his messages.

Analyzing Salvini's populism

With an effective mix of online and offline communication, Salvini has constructed an image of himself as Minister of the Interior, but also as the de facto Prime Minister, all without renouncing the communicative strength and freedom typical of a party leader.

It is a fluid communication where the boundaries between different roles are confused, but also a communication that always has "Salvini" at the core, maintaining his personalbrand. Salvini is always “on message” (Silverstein, 2003). He has the ability to represent a 'consistent, cumulative, and consequential image (or brand) that a public person' appeals to his or her audience (Silverstein, 2003).

In this case, the message that Salvini wants to communicate is an image of a strong leader and common man with good values. This message is spread both offline and online, but especially through the Internet and social media. The use of this communicational structure fits into a strong and precise strategy that is focused on gaining more and more consensus around his ideology.

Salvini uses social networks massively, generating a flow of information in real time, which allows people to follow his actions live. The different formats are used in a profitable way. He releases videos to announce events or talks directly with the social community. He posts interviews if he has to explain the content of the positions taken, or uploads photos to celebrate events.He has been especially successful on Facebook, Italy’s most popular platform, with 34 million active users per month out of an eligible voting population of 46.6 million. Analyzing his Facebook page, we can highlight the main points that have become key to his success.

Salvini the captain, the beast, and Facebook

Using a specially designed software collectively called “the Beast”, thematic fields are monitored to determine the media agenda and the perception that Italians have of the party's core issues. The software analyzes which posts and tweets get the best results, and what kind of people have interacted with them.

Using this data, Salvini's media strategy can be modified through propaganda that stimulates positive feelings as well as anger and fear, and following posts are structured accordingly to followers’ latest reactions. Sometimes, as we can even see posts inciting open hatred and violence against his opponents.

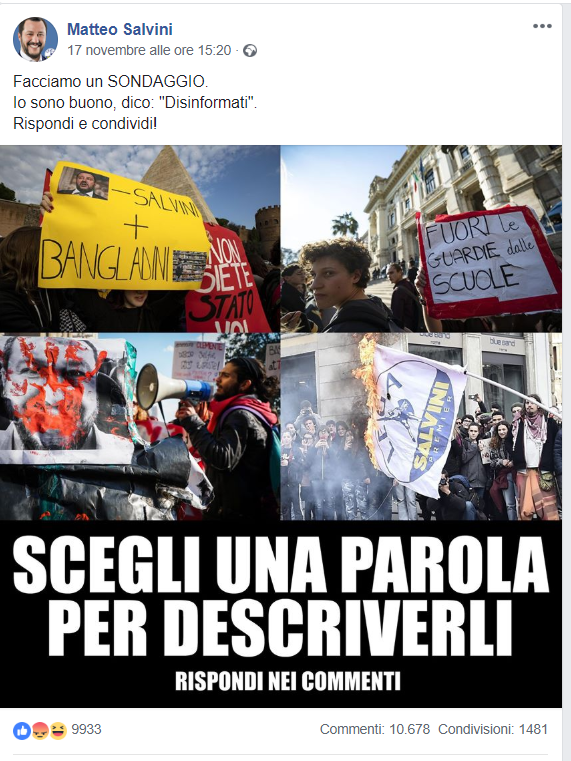

let's do a survey. I am kind, I say: "Disinformed". Choose a word to describe them. Answer and share.

The second instrument is the appeal to the community. Salvini boasts a strong, motivated, and compact community of followers, especially digital followers, with his 3.3 million likes on Facebook. Among this community Salvini is called “the Captain.” Indeed, he claims to be a "Captain" on whom people can rely. In an era of general de-mobilization in political participation, this community is competitive advantage. Especially if a community can be activated both online and offline, as evidenced by the fact that Salvini took part in about 250 initiatives over the last five months. Salvini knows that he can count on his community as a source of legitimization and validation of his leadership.

The third key is polarization. Precisely because we live in a time in which fewer people actively take part in politic life, we must identify enemies, tangible or symbolic, with which to establish an oppositional dynamic. This is why Salvini’s communication agenda is a constant oppositional dynamic that polarizes confrontation and identifies antagonists.

Eviction of Baobab center (tent camp for migrants in transit). Stop to illegality #fromwordsoaction

The fourth instrument is the "common sense revolution," an important piece of his communicative positioning. In his rhetoric, a vote for the Lega is framed as a vote for normality: "it is right to bring back a bit of normality in Italy." The imaginary of "normality" and "tranquility," threatened by external threats and internal deviant behavior, recalls an Italy that was there before. The slogans tap into nostalgia to "make our country great again," as crystallized in Donald Trump's electoral slogan. Moreover "common sense" is a generic concept that allows one to say racist and fascist things with the excuse that they seem sensible because they are shared: they are 'the voice of the people'.

But beyond common sense there is the proclamation of love: "Here there is love, there is no envy, there is no jealousy." Anyone against the Lega is a hater, a “frustrated leftist, which will exhaust the stocks of Maalox in pharmacies.”

Salvini as the typical Italian Family man

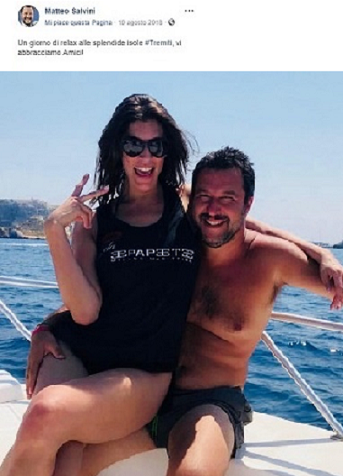

The last key is Salvini's highly informal communication style in talking about his identity. In his posts Salvini appears as a common man, a man of the people, a man with traditional Italian values such as love, friendship, good food, religion and family. This creates a direct relationship with people and distinguishes Salvini from the unpopular caste of politicians. Salvini invites people into his world, posting pictures of his private (and normal) daily life.

I could not leave the beautiful Catania, after the meeting on the earthquake in the Prefecture and an hour walk in the city centre among the people, without trying at least one arancino with meat sauce! What do you say, the PD will attack me?"

A day of relax at the beautiful Tremiti islands, we embrace you, friends!

He floods the Web with family postcards to tell about his last meal, his day at the beach with his fiancée, or the football exploits of his young son, all embellished with photos of him in bermudas or swimsuits.

The language is colorful and characterized by the presence of informal details such as the double question mark. The tone is perpetually passive-aggressive. Ferocious words are always accompanied by "and I say this with a smile, with a hug." Attacks on journalists and opponents end with "I wish you a long and professional life." Further, supporters are always called not only friends, but brothers and sisters, or dads and mums.

Salvini’s common man image is underlined by his clothing. He does not dress as a political leader and does not choose clothing to communicate his political and social position, but rather chooses comfortable clothes that any common man would wear. The peak is when in demonstrations or gatherings he wears a t-shirt with the slogan of that particular event, creating a connection between the demonstrating citizens and himself. The slogans on these t-shirts explicitly stress the political dimension of this seemingly informal, non-political communication of identity.

Stop to Euro

Another interesting feature is the presence of a call to action at the end of most posts. Users who follow the Salvini page are directly involved and invited to express their opinion, becoming an integral part of the communication and discussion process on issues related to the daily life (security in the suburbs, problems regarding family conflicts, comments on the labor market). These messages hope to spark interaction, and thus algorithmic activism in order to push messages to virality.

Salvini's algorithmic populism

One of the most revolutionary characteristics of social media is the ability for everyone to share and spread their ideas, whatever they are: rational or irrational, fair or unfair, true or false. Salvini came to power spreading immigrant panic, anger and anti-pluralistic ideas, creating a community based around them. It's an emotionally sensitive community that is quick to anger, and doesn’t think twice before typing a nasty comment.

And Salvini knows he can count on this community. For example, in a Facebook video from his interior ministry office when he was placed under investigation for kidnapping after refusing to allow migrants to disembark from an Italian coast guard ship.

This is one of the many cases where other Italian politicians might squirm with embarrassment, but Salvini acted like the investigation was a medal of honor and his audience happily cheered. “It is you who asked this minister to control the borders, to control the ports, to limit arrivals, to limit the departure of illegal migrants,” he told his viewers. Every criticism is repackaged as evidence that he is truly fighting for the people, and that he dares to take a stance. It is here that we see the success of his populist rethoric.

References

John B Thompson (2015). The new visibility. University of Toronto

Michael Silverstein (2003). Talking politics. The substance of style from ABE to “W”. Prickly Paradigm Press.

Ico Maly (2018). Populism as a mediatized communicative relation: the birth of algorithmic populism. Tilburg University.

Anton Jager (2018). The myth of “populism”. Cambridge.academia.edu

Nadia Urbinati (2015). Il populismo di Salvini. Repubblica.it.

Steve Scherer (2018). Chestnuts, swagger and good grammar: how Italy's 'Captain' builds his brand. Reuters.

Christian Raimo (2018). Come smontare la retorica di Matteo Salvini. Internazionale.

Franciscu Sedda, Paolo Demuru (2018). Da cosa si riconosce il populismo. Ipotesi semipolitiche. Epublication Université de Limoges.