Black Lives Matter too: from #hashtag to movement

What started out as a public outcry in 2013, following the acquittal of the police officer who shot Trayvon Martin, has since then morphed into a full-blown social movement. This paper analyses the formation and enduring existence of the Black Lives Matter movement through new media.

About this analysis

This analysis of the Black Lives Matter movement (hereafter: BLM) attempts to illustrate how a hashtag, set up by three women, could mobilize the outrage of an oppressed group of people across the US. Special attention will be paid to how a movement that found its origins online, can strongly impact the offline world. I will also emphasize that the movement has flourished in the way that it has, because of the influence of new types of media formats that are available nowadays. The mobilizing ability of the BLM movement is analyzed using the concepts of networked social movements (Castells, 2013), addressivity (Bakhtin, 1984; as quoted by Maly, 2014) and choreography of assembly (Gerbaudo, 2012). Furthermore, the discussion about the identity of the BLM movement is also addressed within the framework of discursive battle (Maly, 2014; Maly, 2016), ideology (Blommaert, 2005) and message (Lempert and Silverstein, 2012).

Messages in the media from and about the BLM movement were analyzed and in order to evaluate the self-presentation of the movement, social media channels, like Twitter and Facebook, were included in the analysis. The Black Lives Matter website was used as an important source to determine the self-presentation and message of the BLM movement. In order to contextualize the movement, media and their presentation of the movement, both supportive and critical, were also analyzed. Content from 2013 to Januari 2017 was used in this analysis, but special attention was given to more recent content.

An introduction: #Blacklivesmatter

The Black Lives Matter movement will not have escaped the attention of those of us who have been observant of the American political system. Since 2013 the movement has grown rapidly, advocating the rights of black Americans both offline and online. The BLM movement epitomizes the power of new media to mobilize public outrage into a movement.

The movement started in 2013 as a hashtag (#BlackLivesMatter) on Twitter. The hashtag was first set up by Patrisse Cullors in response to outrage amongst the black community after George Zimmerman was acquitted for the shooting of young African-AmericanTrayvon Martin. Cullors shared a Facebook post of grief and condolences by Alicia Garza, first using the hashtag to give a voice to the words of both love and outrage. Alica Garza, Opal Tometi and Patrisse Cullors subsequently decided to give a voice to the outraged community of African-Americans, by setting up social media accounts for the movement and by making their movement a presence in the offline community as well, by organising a march and making signs (Day, 2015). As more shootings followed, the movement grew, moving from an online outcry to a movement that was also firmly present in the streets: after Ferguson, people rioted and a “freedom ride” was organized. After Charleston, supporters of Black Lives Matter occupied a shopping mall and later the phrase ‘Black lives matter’ was merchandised and adopted by politicians (Day, 2015).

There are over 30 chapters of BLM across the US at the moment and the Black Lives Matter movement has become a household name in political debates. The BLM movement has a website where it chronicles its own origins and discusses what the movement stands for. What started out as simply a hashtag has become a more 'official' movement with the addition of this website and the creation of chapters across the US. This website also allowed the BLM movement to create a more coherent ideology for supporters to act in accordance with and turned the movement from a hasthag into a real, tangible, social movement that could use political and social pressure to advocate for black people's rights. I will discuss the message and ideology of the BLM movement in the following section.

BLM, message & ideology

Message

Lempert and Silverstein (2012) originally use the concept of ‘message’ when discussing politicians. I have repurposed this idea to talk about the Black Lives Matter movement as a whole, which can be seen as a ‘political actor’ in its own right. A message, in political parlance, is the portrayed character of a political entity. It is crafted from various elements like a biography: issues that the entity is involved with and its style (Lempert & Silverstein, 2012).

The message of the BLM movement is presented clearly on the website of the movement. An important part of message are the issues someone is concerned with. The issues that the BLM movement is involved with seem straightforward: the lives of black people, and specifically the fight for equality. The link with the Civil Rights Movement is one that is quickly drawn and one that is drawn by the movement itself as well. Below is a banner that is prominently featured on the 'who we are' page of the BLM website, quoting civil rights activist Diane Nash. By quoting an activist from the Civil Rights Movement, the BLM movement shows affiliation with this movement and their ideology, already sending the message that their ideals are similar and that they are speaking from within a tradition of black struggle and black empowerment.

Diane Nash is quoted by the Black Lives Matter movement

Furthermore, while the issue of police brutality has become somewhat ingrained in the BLM movement, the movement itself clearly states that it's concerned with a much wider range of issues, also regarding oppression and marginalization within the black community. On their ‘guiding principles’ page the movement noticably states that ALL black lives matter, referring especially to transgender and queer members of the black community (Black Lives matter, n.d.). On the website, the following statement can be foind: "Black Lives Matter is a unique contribution that goes beyond extrajudicial killings of Black people by police and vigilantes. It goes beyond the narrow nationalism that can be prevalent within Black communities, which merely call on Black people to love Black, live Black and buy Black, keeping straight cis Black men in the front of the movement while our sisters, queer and trans and disabled folk take up roles in the background or not at all." (Black Lives Matter, n.d.).

The quote is telling for what the Black Lives Matter movement aspires to be. On the one hand they quote the Civil Rights Movement and identify with it, but they criticise it as well. At it's core, the Black Lives Matter can be seen as a feministic and LGBTQ-friendly version of the Civil Rights Movement. It will come as no surprise then that the civil rights activist the movement quotes, is female. In line with this, the BLM ‘origin story’ is called a ‘herstory’ by the movement, a term mostly associated with feminism. The quoted text speaks out against the history of black heterosexual, cisgendered men taking credit for the work of black, queer, women. The Black Lives Matter movement calls out the black community itself on its treatment of minorities within the community.

While the BLM movement is thus generally associated with police violence and the fight against racism, the BLM movement is also partially a feminist movement for LGBTQ people. In the words of the movement: "To the Black mothers, elders, trans women, queer sisters, femmes, young women and girls and comrades on the frontlines that refuse to let police, politicians, provocateurs, or patriarchy destroy our collective will to get free. We see you." (Black Lives Matter, n.d.) The quote clearly states the support for minorities within the black community that BLM stands for and clearly incites a fight against the patriarcy. Somewhat ironically, this message doesn't seem to have resonated in the way that the outrage against police violence has, showing that the BLM still has more than one fight to win.

While the BLM movement is thus generally associated with police violence and the fight against racism, the BLM movement is also partially a feminist movement for LBGTQ people

Ideology, hegemony and discourse

Using the parts of the message described above, the ideology that the BLM movement promotes can be distilled. An ideology is a perspective on the world, shared by a group of actors. It is often associated with a certain set of symbolic representations, such as discourses, images and stereotypes, as well as with certain behaviours and ideals (Blommaert, 2005). The ideology of the BLM movement is to create a society where black people are no longer marginalized and wherein racism is truly a thing of the past. Emphasis is placed on the fact that all black lives matter equally, and the ideology of the BLM movement includes a strong disapproval ofheteronormativity and the patriarchy, somewhat putting it at odds with people within the black community as well. It would be amiss not to mention the strong influence of feminism and feminist ideology on the ideology that permeates the BLM movement. The BLM movement can therefore be thought of as combating more than one hegemony.

Hegemony is the coming together of power and ideology (Blommaert, 2005). It is a relevant term with which to discuss the fight of the BLM movement. Blommaert (2005) argues that many contemporary anti-racism movements are not anti-hegemonic, because they do not challenge the systemic forms of racism, but simply address the way people act in society. While the idea that black and white people are equal and that society should treat them equally isn't shocking anymore to most people, it is clear that the BLM movement is anti-hegemonic in suggesting that these ideals are currently not being followed and in suggesting that in this there is a deep core of systemic racism. The term 'discursive battle' can be used to explain this.

Maly (2014) describes discursive battles as being "waged over the definition of words, the interpretation of facts, the understanding of the ideology or the general image of the party". The BLM movement is waging a discursive battle to let the majority acknowledge that racism is a structual issue in the US and that black people are still being oppressed. Additionally, the movement is waging a battle to show that the state is not protecting the black community and not providing the resources required to improve the lives of black people. The BLM movement is anti-hegemonic in the way that it questions the assumption that black and white people are already equal in the rights have and in the chances they are offered. Moreover, they also question whether the Civil Rights Movement has already reached its goal. This sets the Black Lives Matter movement apart from the Civil Rights Movement. The Black Lives Matter movement operates in a different timeframe, where oppression of black people is easier to deny. The reality of a black (former) president seems to counteract the narrative that the Black Lives Matter is pushing, making it harder to put forward the idea that black people are not being treated equally.

The BLM movement is anti-hegemonic in the way that it questions the assumption that black and white people are already equal in rights and chances and that the Civil Rights Movement has already reached its goal.

Redefining the meaning of certain words is part of waging a discursive battle (Maly, 2014). In line with this, the BLM movement redefines equality: to be equal does not just mean to be equal by law, but to be treated equally by society and to be given the same chances. As Tometi and Lenoir (2015) state: The Black Lives Matter movement is not a Civil Rights movement, but a human rights one. As they state: "this [the black] struggle is beyond just, “Stop killing us, we deserve to live.” We deserve to thrive, and this requires the full acknowledgement of the breadth of our human rights (Tometi & Lenoir, 2015). The suggestion that the black community is being let down by the government and that a deep-rooted type of racism is still prevalent in contemporary society is inspired by the frameworks set up by the likes of Judith Butler, who suggests that the killings of black people are due to systemic, institutionalized racism in the US (Yancy & Bulter, 2015).

The accusations of systemic racism lead to a counternarrative by opponents of the BLM movement. Opponents of the BLM movement suggest that the inequality that the BLM movement seeks to combat does not exist and they need to "stop complaining". (Peterson, 2015). Take a look at the video posted below, and pay attention to the comments posted on this video as well.

Discussion on the Black Lives Matter Movement and the oppression of blacks between pro and anti-BLM speakers.

In this video, the BLM side of the debate suggests that there is a systemic racial bias, while the anti-BLM side suggests that there is no systemic bias and that the black community is holding itself back. The title of the video is strongly anti-BLM and the comments further extend the narrative put forward by the video, that there is not a systemic bias against black people in society. The comment below, for instance, shows the backlash against the Black Lives Matter movement, combating the narrative that black people are being discriminated against and that the BLM movement is hypocritical and ignorant. It is hardly surprising that the BLM movement has encountered this kind of backlash: nobody likes being called a racist, and as Butler suggests: the racism is often unintended and white people often feel that they are not racist (Yancy & Bulter, 2015). To them, the suggestion that they are racist is seen as an attack, after which a battle quickly breaks out.

The discursive battle waged by the BLM is not one to get society to acknowledge that black and white should be equal, but rather to get society to acknowledge that black and white are not yet equal. This is one of the important differences between the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Lives Matter movement. Another difference is that the internet has enabled the Black Lives Matter movement to grow quickly and organize itself in a way different from the Civil Rights Movement.

#activism: on social movements and new media formats

BLM as a (networked) social movement

I discussed what the Black Lives Matter movement is and what it stands for, but have not answered perhaps one of the most interesting questions: how could a movement that started online through the use of a hashtag lead to a nation-wide movement with 30 chapters around the USA? A comparison with the Civil Rights Movement is a useful way to show how social media and the internet enabled the quick mobilization of the BLM network.

The Civil Rights Movement, mentioned earlier in this paper, instantly comes to mind when thinking of social activism by African Americans. This movement was an important for advocate for the equality of black and white people. Often credited as the ‘spark’ to truly light the fire is therefusal to stand up by Rosa Parks and the following bus boycott throughout Montgomery, led by Martin Luther King in 1955. Similarly, Castells notes that (networked) social movements are “usually triggered by a spark of indignation either related to a specific event or to peak of disgust with the actions of rulers" (Castells, 2013). In this way, social movements have not changed much in the digital age: the spark for the BLM movement was a series of black people being killed by the police. What has changed, however, is the speed and efficiency with which a public outcry can morph into a social movement.

In this way, social movements have not changed much in the digital age: the spark for the BLM movement was a series of black people being killed by police. What has changed, however, is the speed and efficiency with which a public outcry can morph into a social movement

Castells (2013) coined the term 'networked social movement' to describe the new movements that were being enabled by online media. The Black Lives Matter movement certainly agrees with some aspects of the definition of a networked social movement. The key of a networked social movement is that it originates online and often has a clear call to action to mobilize indignation (Castells, 2013). In the case of the Black Lives Matter movement, the first call to action was for people to share their stories of discrimination or police violence, further publicizing the hashtag and allowing the movement to grow exponentially. Additionally, the BLM started online and the internet is an important part of the movement. It would be easy to suggest that the BLM movement is a networked social movement and attribute its success to that fact, but the reality is more complicated and the BLM movement differs from Castells's definition of a networked social movement in several ways.

An important aspect of networked social movements is that they are leaderless: they are led by members of the community and are relatively fluid. The BLM movement is not leaderless: founders Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi and Patrice Cullors take on a prominent leadership role in speaking to the media and presenting the 'official' BLM agenda. The BLM movement calls itself a "leaderfull movement", meaning it is led by a collection of local leaders (Black Lives Matter, n.d.). This also points to another way in which the BLM movement is not truly a networked social movement: the movement has a very clear programme, which is presented on the website and consistently communicated by the leaders to the public. This does not agree with Castells' definition of a networked social movement, which suggests that these movements are rarely programmatic. Finally, networked social movements are spontaneous. While the BLM movement started out this way, it has solidified itself as a true organisation that no longer operates purely on spontaneous anger, but rather on a program with clear goals and actions in mind. As the BLM movement itself states: Black Lives Matter is "Not a moment, but a movement" (Black Lives Matter, n.d.).

Characterizing the BLM, therefore, can best be accomplished by concluding that the BLM movement is a hybrid between a new social movement and a networked social movement. The characteristics of networked social movements give the BLM movement a strong online presence and a platform for the networked community to interact with one another and to speak out. The characteristics of the more traditional new social movements, such as a clear leadership and program, allow the BLM movement to carry out a strong, singular message and to organize offline actions effectively. It might be that the success of the BLM movement can be found in the balance between a new and a networked social movement.

New media: Hacking the hegemony

The features of networked social movements that fit the BLM movement certainly aided the BLM movement in growing as fast as it has. An article by Wired, wich drew a comparison between the BLM movement and the Civil Rights Movement poignantly illustrates how new media have helped the BLM movement to grow quickly (Stephen, 2016). Stephen (2016) describes the large infrastructure needed to report violence against black people on the streets, during the time of the Civil Rights Movement. Stephen emphasises that it was not the Civil Rights Movement itself that controlled the most important technology and media for their movement: it was the film crews, that were not a part of the movement. They relied on having to use media that were not controlled by those in the movement and therefore, the Civil Rights Movement had to contend with a Media Hegemony. New media have turned the tables for social movements like the BLM movement.

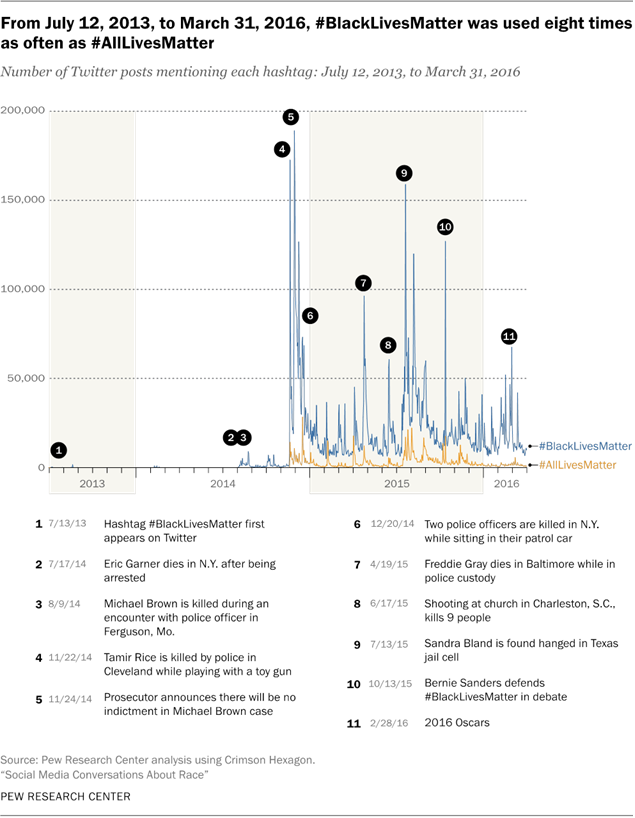

Trends of the hashtags #Blacklivesmatter and #alllivesmater on Twitter

New media have enabled social movements to no longer be dependent upon possibly hegemonic mass media, but to express their ideology in their own way, through their own channels. New media, according to Castells (2007), are spaces that are largely beyond the control of governments and therefore allow the flourishing of anti-hegemonic ideas. The hegemonic media monopoly that the Civil Rights Movement had to contend with, is no longer a big issue for the BLM movement. New media, and mainly Twitter, allowed the BLM movement to produce a counter-narrative and become a counterbalance to the hegemonic media and, by extent, hegemonic society. It was new media that allowed thousands of African Americans to share their stories and to show that racism was still a very real problem in the USA. The graph above shows how new media were used by BLM supporters to bring to light different instances of police violence against black people. The BLM movement did not need to approach the media to tell the story about discrimination in the USA: they invited black people to share their stories first-hand, on their own platform, allowing the community to write its own story and to shine a light upon issues that had been somewhat left in the dark before.

Furthermore, Twitter, according to Bonilla and Rosa (2015), can be used as a tool for protesting and campaigning in itself. New media and especially Twitter, due to its fast-paced nature, allow the following of events in real-time. Through the hashtag #Ferguson, people could stay up to speed with what was happening in Ferguson and how the community responded to all the events. Livestreams and Tweet-reports enabled what Bonilla and Rosa (2015) call a 'shared temporality'. People tweeting about Ferguson, wherever they were, felt like they were participating in the campaign against police brutaility. The fast-paced access to news, combined with the freedom to contribute to the narrative of a specific issue through hashtags, makes Twitter a particularly suitable platform for campaigns such as the #iftheygunnedmedown campaign. The hashtag #Ferguson, then, was not just people talking about the issue and sharing the news, it was people intentionally making sure the hashtag would be highly visible. It is clear hashtags are often used as a campaigning tool, instead of just as an archiving one.

The BLM movement did not need to approach media to tell the story about discrimination in the USA: they invited black people to share their stories first-hand on their own platform, allowing the community to write its own story and to shine a light upon issues that had been somewhat left in the dark before.

It is easy to conclude that new media are the holy grail of social movements, and in a way they are. However, there is an important hero for social movements that is often unsung: Net Neutrality. This Net Neutrality has been a point of discussion for governments for some time and is a crucial part of why new media allow for the growth of social movements. Net Neutrality is the idea that the internet should provide equal access to all content, regardless of who produces it or what the ideology behind the content is. It is, in a way, the rule protecting free speech on the internet. This freedom to disseminate any kind of information, be it hegemonic or anti-hegemonic, is important for social movements.

Tufekci (2014) illustrates this by using the Ferguson case as an example to show the importance of Net Neutrality for gaining visbility for movements. The hashtag #Ferguson allowed the dissemination of information from a place that would otherwise have been ignored. It drew the attention of the mainstream media to the drama unfolding in Ferguson and allowed the streaming of videos to make this visible. #Ferguson was trending on Twitter, but as Tufekci (2014) notes: it took longer to take off on Facebook. Tufekci suggests that this is due to the algorithmic filtering by Facebook, which makes it a more non-neutral website. Tufekci (2014) suggests that perhaps it was not just the social media, but the net neutrality accompanying it, that allowed the Ferguson conversation to grow as it did. It was Net Neutrality that was important in allowing the BLM movement to grow, by allowing a financially and socially oppressed group of people to speak out and be visible. With Net Neutrality possibly being challenged by the government, one wonders for how long social media will be the free, anti-hegemonic tool that Castells (2007) proposed it to be.

Finally, with the proposed juxtaposition of government, hegemony and mass media against protesters and new media being called into question by president Trump's rejection of the mass media, it will be interesting to see how the shifting relations between the media and hegemony will affect new social movements. With the mass media seemingly increasingly turning against the hegemony, and president Trump utilizing new media to an unprecented amount, the landscape of hegemony and media might see a change again sooner rather than later.

When a #hashtag takes to the streets

Black Lives Matter protesters in Seattle

Social networks might seem like the dream of any social movement and I just explained how it was indeed these new media networks that allowed the Black Lives Matter movement to exist and grow in the way that it has. It is, however, good to take a critical look at what it means to be a member of an online social movement, and how that translates offline. The term ‘slacktivism’, coined by Morozov (2014) describes how ‘activists’ can take action from their couch by, for instance, sending angry tweets. Morozov calls this kind of activism ‘slacktivism’: there is no risk involved, no real effort or danger and it ultimately leads to little real action or change. Critics of online activism suggest that this type of ´slacktivism´ erodes the spirit of what it means to be an activist and state that these ´slacktivists´ do not actually promote any change.

While the idea of slacktivism is certainly one to be aware of, the BLM movement seems to not have suffered from it. The BLM movement has been incredibly successful in taking its protests to the street, in mobilizing people. According to Elephrame (2016) there have been over 1600 demonstrations by the Black Lives Matter movement. While some of these protests are made by just one person, many of these are planned centrally, by a chapter of the BLM movement. The BLM movement is successful in mobilizing people, because it doesn't only use social media to allow people to speak out, but also to organize offline protests. This is what Gerbaudo (2012) calls choreography of assembly. Gerbaudo (2012) suggests that social media reconstruct how social media are thought of as a tool for collective action, by setting dates and providing instructions for protesters. In this way the social network becomes more grounded in the real world, which enables the movement to 'step out' into the offline world. Gerbaudo (2012) also suggests that social movements online are in fact not leaderless, but are led by so called 'choreographers', who set the scene for people to act in. I previously discussed that the BLM movement is not a leaderless movement, and I suggest that it is because of this that the choreography of the BLM movement could be carried out in a clear and structured manner, allowing for the many big protests that swept the country wave by wave.

The BLM movement has used new media to organize protests. Facebook events is an important tool for the BLM movement. The Facebook page of the BLM movement and its separate chapters show the events and protests, and when and where they will happen. In terms of a choreographed routine: they provide a stage and a time, but the players who will stand on the stage are not predetermined. The BLM movement website is used in much the same way, providing a 'calendar' with events for BLM protesters to attend, if they want to, and the possibility to start their own events as well. It is this planning that allows thousands of people to come together on a regular basis with just one thing in common: they think black lives are important and are willing to participate in events to show it.

Black Lives Matter Chicago uses Facebook events to plan and communicate actions by the movement

It is clear that social media were important in planning the BLM movement protests, but what made people willing to take part in rallies that they knew could have dangerous consequences? I suggest that the reason that so many people were willing to take to the streets for the BLM movement is due to the strong addressivity of the Black Lives Matter movement. Addressivity (Bakhtin, 1984; as quoted by Maly, 2014) means that a message speaks to a certain audience, because of the way the message is formulated or because of the sentiment the message contains. A message tailored to a specific audience will be more addressive and will therefore resonate more with the audience.

The BLM movement is highly addressive to a specific group of people: black people. Research by Charity (2016) shows that most of the people who speak online about the BLM movement are black. This is hardly surprising, but it does illustrate why the movement succeeds at motivating people: because it speaks to people directly. The name of the movement tells black people, who have frequently experienced racism and marginalization, that they matter. It speaks directly to the black community: it is not stating in a vague way that every person should be treated equally, or that racism is bad, or even that it is not real: it's being honest, proud even, in declaring that black people matter. It makes sense that this is a much more personal, mobilizing, address than simply retweeting outrage about an injustice that one is not personally hurt by, to make oneself feel better, which is a type of slacktivism. This time it’s personal, and when it’s personal people don’t slack.

The strong addressivity of the Black Lives Matter movement is amongst the factors that it owes its success to, but it's also what causes it to be highly polarizing. The name of the movement itself seems to somewhat exclude anyone who isn't black in the eye of many opponents, which has caused them to adapt and adopt the Black Lives Matter rallying cry in a very different way. It is the high addressivity of the BLM movement that caused what I term the 'war of hashtags' and the discursive battle of what BLM truly stands for.

The power of words: heroes or haters?

The BLM movement is involved in a range of discursive battles (Maly, 2014), both online and offline. I already discussed the battle that the BLM movement is waging to show that black people are still being oppressed and are not yet equal. While this is certainly an interesting topic for a discursive analysis, I am focusing on another discursive battle the BLM movement is waging, namely a discursive battle that concerns the very core of the BLM movement. The BLM movement, that characterizes itself as a social justice group, has been termed by opponents as a hate group. The BLM movement is therefore waging a discursive battle over what the BLM movement is at its core.

I discussed before that the high addressivity (Bakhtin, 1984; as quoted in Maly, 2014) of the BLM movement allows it to be highly mobilizing. However, it is also this high amount of addressivity that fuels the counternarrative of the opponents of the movement that the BLM movement is a hate group, only concerned with black people. The slogan "Black Lives Matter" is highly addressive to black people, and therefore it seems to exclude non-black people. This exclusion is even labelled as racism (or 'reverse racism') by some people, such as Perazzo (2016), who compares the movement to the Black Panthers. This, in combination with riots and violence by (supposed) BLM supporters, is being used by BLM opponents to frame the BLM movement as a hate group.

One of these opponents is Spollen (2015), who calls the BLM movement a 'hate group', citing violent Tweets by supporters and accusing BLM supporters of 'laying siege to towns'. Spollen (2015) also describes the effect of a strongly addressive slogan, stating: "Your life matters. To proclaim that one race's life matters more than another's is inherently racist by definition." Note that the criticism of the BLM movement does not stem from the idea that black lives do not matter, but from the idea that the BLM movement is problematic as a movement. This narrative is also clear in the text for a petition to classify the BLM movement as a hate group, where it states: "Black lives matter have endorsed hate and violence against citizens and Police simply because of the color of their skin." (Hamilton, n.d.). The counternarrative that is created by BLM opponents is one that stresses that the BLM movement only cares about black people and is even anti-white or anti-police. Below is an excerpt from a speech by Milo Yiannopoulos, senior editor for the extreme-right Breitbart news, calling the BLM 'the last socially acceptable hate group in America'. In the speech, totalling a length of 2 hours and 31 minutes, Yiannopoulus discusses that the BLM movement is a hate group and that racism is not a reality anymore.

The BLM movement itself responds to the accusations of them being a hate group by stressing that they do not hate police officers and that, in fact, all lives matter to them. The movement addresses the claim that the BLM movement hates white people in their article '11 major misconceptions about the BLM movement', stating: "The statement “black lives matter” is not an anti-white proposition. Contained within the statement is an unspoken but implied “too,” as in “black lives matter, too,” which suggests that the statement is one of inclusion rather than exclusion." (Black Lives Matter, n.d.). Similarly, the movement states that it does not hate police officers, but seeks to improve the way that police officers interact with the black community. The battle for the identity of BLM has not yet been decided and will doubtlessly continue for some time, with tensions rising during the period leading up to Donald Trump's inauguration as president.

#Alllivesmatter and the war of hashtags

One of the reasons the Black Lives Matter movement has picked up in the way it has, is undoubtedly its name. The hashtag is short, clear, and strong: it instantly conveys what the movement stands for without needing further explanation. It is hardly a surprise that the format of the hashtag has been adopted by other movements, like #Asianlivesmatter and #Translivesmatter. Where these examples probably come from a place of admiration and willingness to follow in the footsteps of the BLM movement, the BLM movement has requested people not to adapt the hashtag in order to not 'dilute' the conversation, stating: "Please do not change the conversation by talking about how your life matters, too. It does, but we need less watered down unity and a more active solidarities with us, Black people, unwaveringly, in defense of our humanity". (Black Lives Matter, n.d.) The BLM movement suggest that 'plagiarism' of the BLM format can be used to undermine the power that the movement has, which is perhaps exactly why its opponents have chosen to do so in the discursive battle that they are waging.

Protesters march holding #bluelivesmatter signs

Two hashtags used by opponents of the BLM movement are '#Alllivesmatter' and '#Bluelivesmatter'. Both hastags were developed in response to the Blacklivesmatter hashtag and have served as a tool in opposing and reframing the BLM message. 'Blue lives Matter' even became a movement itself, advocating the importance of law enforcement and the right for police officers to be protected (Blue Lives Matter, n.d.). The borrowing of the format used by the BLM movement (Xlivesmatter) is a clever trick by the movement to reframe the statements made by the BLM movement. The BLM movement does not state that police lives do not matter, nor do they advocate for violence, as I discussed earlier, but by pitting the term ‘Blue lives matter’ directly against the BLM movement, the counter-movement suggests that the BLM movement does in fact advocate violence against police officers. The hashtag #Bluelivesmatter is used to change the meaning of the #Blacklivesmatter movement, by suggesting it means ‘#ONLYblacklivesmatter'. This is in line with the discursive battle that is going on and the counternarrative that the BLM is a hate-group that hates police officers.

The #Alllivesmatter hashtag is similar to the Bluelivesmatter hashtag and is perhaps a stronger opposing hashtag than the bluelivesmatter one. The alllivesmatter hashtag seems to give those who follow it the moral high ground over the BLM supporters. It furthers the narrative that the BLM movement does not care about the lives of those who are not black. The #Alllivesmatter hashtag also furthers the narrative that black people are already equal and that there is no structual racism present in US society. As Butler (2015) puts it: "If we jump too quickly to the universal formulation, “all lives matter,” then we miss the fact that black people have not yet been included in the idea of “all lives.” (Yancy & Bulter, 2015). The 'Alllivesmatter' hashtag, according to BLM supporters, distracts from the message made by the BLM movement and is therefore a strong, yet subtle, weapon in the discursive battle being waged against the BLM movement, as the comic below shows.

While hashtags might seem like a small, unimportant, part of online discourse, I have shown that hashtags can send a very profound message with very little words. The hashtag that an actor uses to describe a person, movement or action can effectively frame it in a certain way. Hashtags, therefore, should not be overlooked in studying political parlance.

Concluding: where do we go from here?

The Black Lives Matter movement is a movement in contemporary US society that is as polarizing as it is powerful. In this paper I discussed the history and ideology of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as why the movement managed to be as successful as it has been and continues to be. I also touched upon the discursive battle that the BLM is waging with its opponents and the war of hashtags being waged on Twitter.

I propose that the BLM movement has combined the features of new social movements and networked social movements with strong addressivity in order to gain visibility and mobility. The BLM movement has shown how the internet can enable public outrage to grow into a structured and powerful social movement. With the political landscape in the US changing dramatically with the presidency of Donald Trump and net neutrality being threatened, the future of the BLM movement is as of yet uncertain. It is difficult to predict where the Black Lives Matter movement will go from here, but one things is clear: the internet should not be underestimated as a tool for mobilizing outrage, for better or for worse.

References

Black Lives Matter (n.d.) #SayHerName: A Reflection from Mary Hooks, BLM: Atlanta.

Black Lives Matter (n.d.) 11 Major Misconceptions About the Black Lives Matter Movement.

Black Lives Matter. (n.d.). About the black lives matter movement

Black Lives Matter (n.d.) Guiding principles

Black Lives Matter (n.d.) Herstory

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Blue Lives Matter (n.d.) Organisation.

Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). # Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42, 4-17.

Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International journal of communication, 1(1), 29.

Castells, M. (2013). Communication power. OUP Oxford.

Charity, J. (2016). How #BlackLivesMatter Turned Hashtags Into Action. Complex UK.

Day, E. (2015). #BlackLivesMatter: the birth of a new civil rights movement. the Guardian.

Elephrame. (2016). Read this list of 1,620 Black Lives Matter protests and other demonstrations.

Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Social media and the choreography of assembly: Findings from a comparative research. Tweets and the Streets.

Hamilton, M. (n.d.). Colorado Governor: Label Black Lives Matter a Hate Group!

Lempert, M. and Silverstein, M. (2012). Creatures of politics. 1st ed. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press.

Maly, I. (2014). New media, new resistance and mass media

Maly, I. (2016). ‘Scientific’ nationalism. Nations And Nationalism, 22(2), 266-286.

Miller, R. W. (2016). Black Lives Matter: A primer on what it is and what it stands for. USA TODAY. Last retrieved on 4/12/2016.

Morozov, E. (2011). The net delusion. 1st ed. New York: Public Affairs.

Perazzo, J. (2016). The Profound Racism of 'Black Lives Matter'. Frontpage Mag.

Peterson, J. (2015). 'White Privilege' Is Not What Is Holding Blacks Back Today. CNS News.

Spollen, A. C. (2015). Black Lives Matter Has Morphed Into A Hate Group. It's Time To Treat It As Such. IJR.

Stephen, B. (2016). How Black Lives Matter Uses Social Media to Fight the Power. [online] WIRED. Last retrieved on 4/12/2016

Tometi, O. & Lenoir, G. (2016). Black Lives Matter Is Not a Civil Rights Movement. TIME.com

Tufekci, Z. (2014). What Happens to #Ferguson Affects Ferguson: – The Message. Medium.

Yancy, G. & Butler, J. (2017). What's Wrong With 'All Lives Matter'?. Opinionator