How Dutch conspiracy media include TikTok in their grand conspiracy theories

TikTok has been widely discussed and criticized in mainstream media. But the app has also been hotly debated by conspiracy media. How do they talk about TikTok? And how do they employ TikTok controversies to perpetuate their grand conspiratorial narratives? This article zooms in on three emblematic case studies taken from Dutch conspiracy media positioning themselves as news outlets to examine how TikTok is framed as 1) censoring counter narratives, 2) a propaganda channel for the elites, and 3) part of a Chinese threat to the West.

Before delving into these case studies, I first sketch the context of the TikTok controversy and the 'ideological' struggle in conspiracy media. I then highlight the methods of discourse analysis I use to examine the case studies, after which I introduce the data from which these case studies are taken.

The TikTok controversy in conspiracy media

As TikTok grows into one of the most popular social media apps in the world, the criticism against the app also grows. Critics point to the addictive nature of TikTok (St George, 2023), the tendency of the algorithm to pull users into rabbit holes of extreme content (Wall Street Journal, 2021), the proliferation of misinformation on the app (KRO-NCRV, 2023), and invasions of privacy (Kircher, 2023).

Additionally, the Chinese origins of TikTok’s mother company ByteDance are cause for concern for governments around the Western world. In a host of countries, including Australia, Denmark, the UK, Belgium and the Netherlands, the use of TikTok is at least partly prohibited for government officials out of fear for Chinese espionage and cyberattacks (Navlakha, 2023). During his US presidency (which was marked by a trade war with China), Donald Trump even attempted to ban TikTok completely (Trump, 2020).

Clearly, TikTok is controversial. This controversy has largely played out in the reporting of mainstream media. But that does not mean TikTok is ignored on the fringes of the media landscape. This article zooms in on one particular fringe where TikTok has been scrutinized: conspiracy media, where the app is framed in the context of 'ideological' struggle, censorship and propaganda.

Conspiracy media as sites of 'ideological' struggle

Even though conspiracy theories have been around for ages (Van Prooijen & Douglas, 2017), dedicated conspiracy media are a much more recent phenomenon. Conspiracy media usually operate at the fringes of society on dark platforms like 8Kun and 4Chan (Zeng & Schäfer, 2021), dedicated websites, video channels and podcasts. But in recent years, these conspiracy media and their narratives have also surfaced in mainstream society. The QAnon message boards on 8Kun have been linked to the US insurrection on 6 January 2021 (Rubin et al., 2021), Alex Jones has been on a widely covered trial for spreading conspiracy theories in his podcast Infowars (Williamson & Steel, 2023), and the Dutch conspiratorial broadcaster Ongehoord Nederland was granted a public tv and radio broadcasting license in 2022 (NOS, 2021).

Conspiracy media vary widely in the kinds of content they produce and the narratives they traffic (Varis, 2018). What they all have in common, however, is that they are epistemologically grounded in the assumption that the truth is ‘out there’, but that this truth is deliberately hidden from ‘the people’ by a nefarious group of cultural, governmental and/or business elites. They are generally opposed to global power structures, like supranational (governmental) organizations such as the United Nations, European Union, and World Health Organisation. But they also turn their criticism towards big media corporations like Meta and Google, as well as ‘industrial complexes’ in the pharmaceutical (‘Big Pharma’), agricultural (‘Big Agro’ in Dutch) and military (‘The Military-Industrial complex’) industries.

Of course, there are exceptions to this rule of thumb. In specific contexts, global power structures could actually be praised in conspiracy media, e.g. how the early internet was actually hailed as a tool for opening up and democratizing flows of information, with the formation of globally connected online conspiracy communities as a salient consequence. In the context of this study, however, these power structures are predominantly approached with suspicion.

Conspiracy culture is rooted in a constant struggle against hegemonizing power structures and ideologies

On a surface level then, we can’t disqualify conspiracy media for being uncritical. Most of their discourse revolves around criticizing power. Their criticism, however, should be understood as deeply populist. Conspiracy culture as a whole is rooted in a constant struggle against hegemonizing power structures and ideologies. To speak with Antonio Gramsci (2010), the conspiracy theorist’s worldview departs from the notion that there is a small, powerful elite that controls both the base (capital, industry, materials, etc.) and the superstructure (media, culture, law, politics, etc.) of society in order to oppress ‘the people’.

Contrary to Gramsci, however, conspiracy culture is not engaged in a thorough material and class analysis of specific power structures in society. Rather, it takes Gramsci's analytical framework and reduces it to a populist discursive template (Lacau, 1977) used to separate society into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite' (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2012). These two groups act as empty signifiers (Lacau, 1977) which can be filled at will by the conspiracy theorists to sustain their conspiratorial narratives and worldviews in any situation.

As central hubs of ‘knowledge’ production and distribution in conspiracy culture, conspiracy media use this populist template to perpetuate their narratives and worldviews. They frame these as an ideological struggle between a neoliberal, technocratic, corrupt elite (Them) and a pure people of free thinkers under the guise of ‘critical journalism’ (Us). This populist framework allows for specific ideologically positions to be framed as the voice of the people and become normalized. As such, they give themselves the freedom to discursively construct TikTok as part of in their 'ideological' narrative without the burden of a structural analysis.

The conspiracy theories spread in conspiracy media might be fake (though we cannot assume them to be fake a priori). And the ideological struggle against 'the corrupt elite' imagined by conspiracy theorists might be more populist than ideological (though it is not devoid of ideology). But these theories and struggles do structure political and social reality. Sometimes with violent consequences. That makes it interesting to investigate how these media operate, how their narratives are constructed and spread, and how current events are included in these narratives to perpetuate the imagined 'ideological' struggle.

TikTok as part of a larger story

The controversies surrounding TikTok make for an interesting case study of the inclusion of current events in conspiracy narratives. As a big media company linked to the Chinese government (according to the mainstream narrative) that actively works together with supranational organizations (e.g. the WHO during the corona pandemic), TikTok seems to be a perfect candidate for conspiracy media to scrutinize.

The goal of this study is to lay bare the specific discursive practices conspiracy media deploy to connect the TikTok controversy to existing narratives of populist antagonism while maintaining their image as ‘critical journalists’ in the conspiracy milieu. Specifically, this study zooms in on how Dutch conspiracy media discursively link TikTok to the larger narrative that a powerful elite attempts to hegemonize the flow of information through censorship and propaganda. As such, the research question central to this inquiry is:

How do Dutch conspiracy media discursively frame TikTok in relation to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda?

Method: Discourse analysis

If we wish to understand how the TikTok controversies are included in the existing narratives of conspiracy media, we must turn our attention to the discourse these media employ. As “all forms of meaningful semiotic human activity seen in connection with social, cultural, and historical patterns and developments of use” (Blommaert, 2005), discourse is essential in meaning-making and structuring social reality. Through discourse we can label things, people and events as ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘important’, ‘desirable’, ‘detestable’, etc. Through intertextual repetition, these categorizations can become enregistered ‘common sense’ in a specific context.

For example, in the context of a court trial, no one bats an eye when a lawyer addresses the judge with 'your honour'. We know this is how you should address a judge thanks to the social, cultural and historical patterns of how a judge is addressed. We read it in court procedures, we learn it in law school, and we see it in courtroom dramas on Netflix. It has become common sense, and every time it is used, the power relationship between the judge and the lawyer is reproduced.

We need discourse analysis to analyse the common sensical attributions given to TikTok

At that point, when no one bats and eye anymore, such a snippet of discourse becomes an observable manifestation of ideology. It is a symbolic form that points towards the ideas, norms, conventions and power relations that are produced and diffused by the apparatus of state, media and social institutions (Althusser, 1970; Thompson, 1990), as well as “the specific contexts of action and interaction within which these mediated symbolic forms are produced and received” (Thompson, 1990). At the same time, however, the common sense nature of the discourse also obscures the ideology it reproduces. The explicit becomes increasingly implicit with every re-use, to the point where a statement like 'your honor' appears ideology-less at face value.

Investigating historical patterns of use

In order to lay bare the ideology embedded within the 'critical' 'journalistic' discourse of conspiracy media, we thus need the sophisticated methodological tools of discourse analysis (Blommaert, 2005). With them, we can analyse the commonsensical attributions given to TikTok and how they relate to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda. The concepts of intertextuality and indexicality will be central in this analysis.

Intertextuality focusses on how texts are connected to previous texts (Blommaert, 2005). In our case: how texts are connected to existing narratives constructed in previous texts. In the digital conspiracy media under investigation, intertextuality takes on two forms. First, explicit intertextuality manifests itself as quotes and hyperlinks that directly connect the texts in which they occur to previous texts. Second, implicit intertextuality occurs as terminology, references and word use that derive their meaning in the specific contexts in which they are used from unmentioned historical patterns of use.

Links and references point to social norms, roles and identities

These are not just shortcuts for continuing existing narratives in new texts. They also point to social norms, roles and identities. The concept of indexicality focusses on how these extra layers of meaning emerge out of text-context relations (Blommaert, 2005). In the case of conspiracy media, their discourse needs to report on current events, but also uphold both their affiliation with 'the people' in the populist narratives of conspiracy culture and their identity as ‘professional journalists’. Indexicality allows us to investigate how this metanarrative emerges from their discourse.

Together, the concepts of intertextuality and indexicality will help us to lay bare how conspiracy media connect TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda while maintaining their identity as legitimate journalistic sources of ‘knowledge’.

Data: Dutch conspiracy media

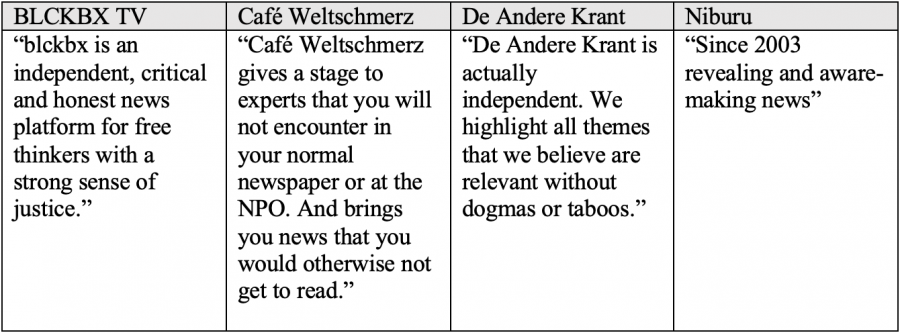

The scope of this research is limited to five digital media from the Dutch conspiracy milieu that explicitly position themselves as news outlets: BLCKBX TV, Café Weltschmerz, De Andere Krant, Gezond Verstand and Niburu. Together, these conspiracy media provide a wide and varied vista on the online Dutch conspiracy media landscape.

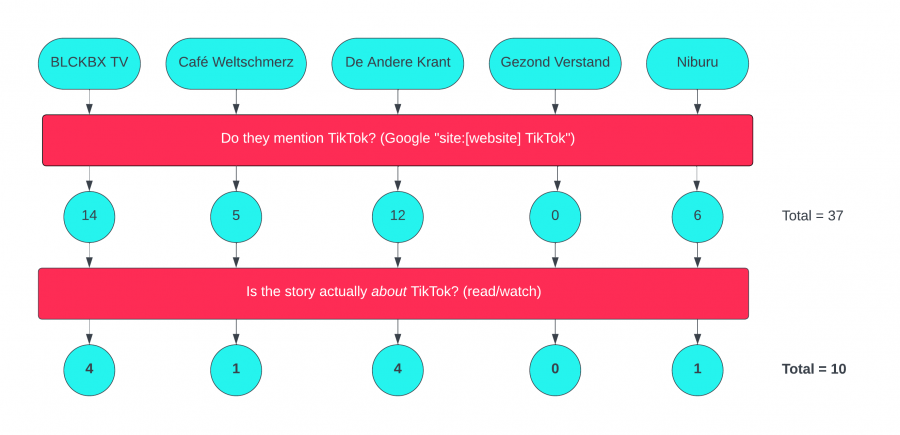

The websites of all five media were parsed for content about TikTok using the Google search query “site:[website] TikTok”, which searches all pages on a website for the word ‘TikTok’. This resulted in a total of 37 webpages that mentioned TikTok. Most webpages that mentioned TikTok were found on the websites of BLCKBX TV (14 webpages) and De Andere Krant (12). 6 pages were found on the website of Niburu and 5 on the website of Café Weltschmerz. Notably, Gezond Verstand did not publish any online content about TikTok.

All 37 webpages that mentioned TikTok were read (and, if the webpage contained a video, watched) to determine if the page actually was about TikTok. This process excluded 27 webpages, for example because they only mentioned TikTok in passing, or because they only referred to a TikTok video in an article about another topic. That means 10 articles remained for analysis: 4 by BLCKBX TV, 4 by De Andere Krant, 1 by Café Weltschmerz, and 1 by Niburu. The first article was published on 11 March 2022, the most recent one was published 24 July 2023.

Figure 1: data collection process

Table 1: analysed data

All 10 webpages were read/watched multiple times and analysed according to the methods of discourse analysis described above. In the remainder of this article, I will delve into three emblematic articles as a case study analysis of the narratives found in the data that connect TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda. But first, I will give you an overview of the discursive framing of TikTok as part of Big Tech and the mainstream media industry, as it will inform the following case studies.

TikTok and Big Tech

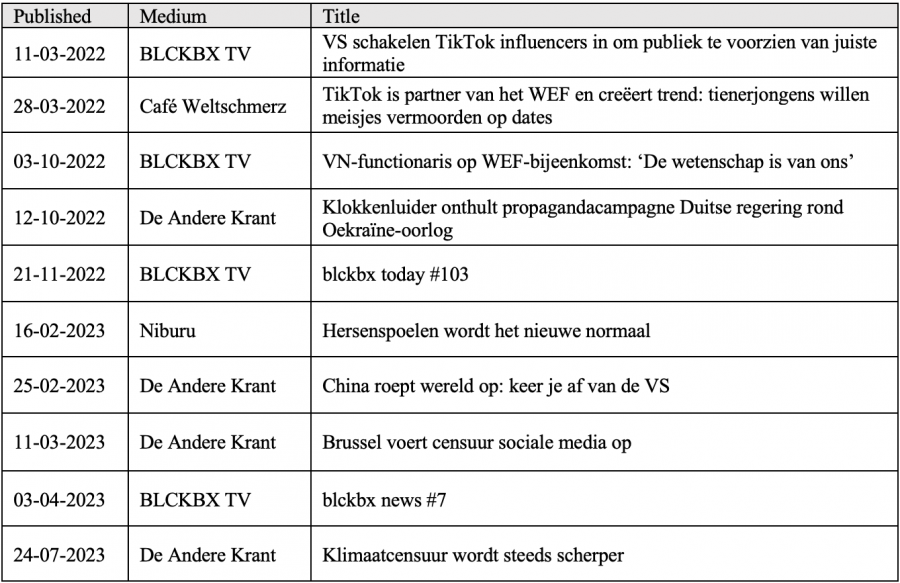

Conspiracy media are generally opposed to global power structures and big industrial complexes. In recent years, this has made Big Tech a regular subject of their critique. Companies such as Google, Meta and X (formerly Twitter) and their executives are framed as part of a global elite that tries to oppress the masses and hide the truth about what is happening in the world. In the data, TikTok is repeatedly connected to these Big Tech companies and a selection of (global) governmental institutions.

It becomes common sense that TikTok is part of ‘Big Tech’

In the 10 webpages, TikTok is connected to other media companies 19 times. As illustrated in Figure 2, most of these connections are made with big Silicon Valley companies/platforms, such as Google, YouTube, Facebook and LinkedIn. In individual cases, TikTok is connected to more local media like the German Axel Springer and the Dutch Nu.nl. These connections are often made in articles where the author sums up actions taken by a selection of media companies in service of the global elite. For example: in the article "Klokkenluider onthult propagandacampagne Duitse regering rond Oekraïne-oorlog" (Whistleblower reveals propaganda campaign from the German government surrounding the Ukraine war) in De Andere Krant, the author writes:

“An internal document, leaked by a whistle blower, shows that the government in Berlin is conducting a structured campaign to combat 'disinformation' about the Ukraine war. This involves collaboration with American and British organizations, media group Axel Springer, Google, YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Tiktok [sic] and Linkedin [sic], and even children's programs and educational institutions are influenced.” (Penning, 2022).

By repeatedly placing TikTok in lists of media/tech companies like in the quote above, TikTok is not seen as a media company deviating from the mainstream Silicon Valley companies/platforms. Rather, it is understood as similar and on par with these companies/platforms. As such, it becomes common sense that TikTok is part of this industrial ‘Big Tech’ complex that enforces and reproduces the ideologies of a 'corrupt elite'.

Figure 2: discursive connections with TikTok

In a similar fashion, TikTok is discursively connected to governmental institutions a total of 12 times (Figure 2). In the data, the social media platform is most often connected to supranational institutions, like the UN, the EU, NATO and the World Economic Forum. One example is the article "VN-functionaris op WEF-bijeenkomst: ‘De wetenschap is van ons'" (UN-official at WEF meeting: 'the science belongs to us') by BLCKBX TV, which revolves around a UN official discussing how they work together with Google and TikTok to tackle disinformation at a WEF-meeting.

Just like with the connections to media companies, we also see TikTok being connected to local governmental institutions (American government, German Government, the Dutch GGD) as part of localized conspiracies. The article “VS schakelen TikTok influencers in om publiek te voorzien van juiste informatie” (US uses TikTok influencers to supply audiences with correct information) is a good example of this, as it discusses how the White House briefed a group of TikTok influencers on what information they should share with their followers about the war in Ukraine.

These are just some examples. In every article included in the current analysis, we find TikTok being connected to other media companies and to governmental organizations, often to both. Most of the times, these connections centre around how organizations like the EU or the American government use media companies like Google and TikTok to control the flow of information. TikTok is thus framed as an important pawn in the efforts of a nefarious elite to control the masses. I’ll go into this populist frame in more detail in the case studies below.

Three narratives

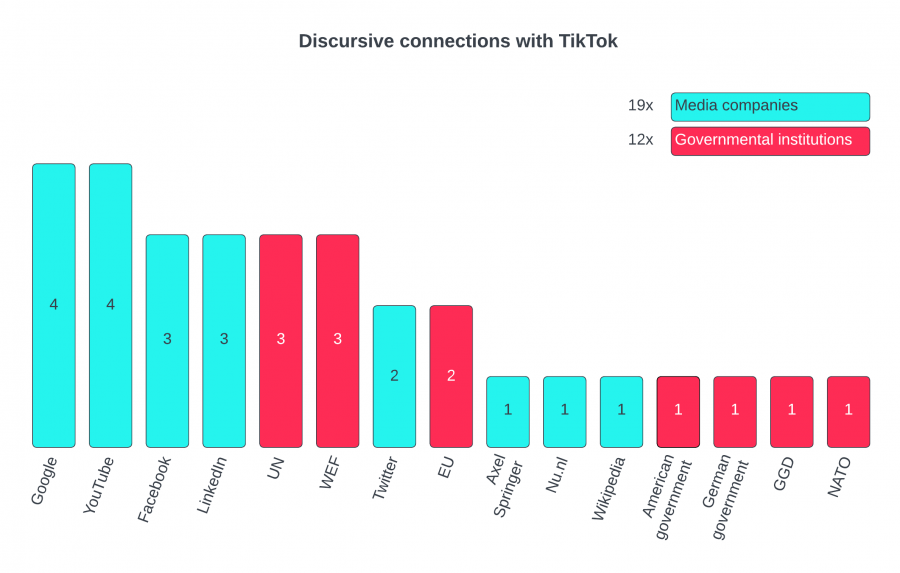

In the data, three main narratives emerge that are used to connect TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda:

- TikTok is censoring counternarratives;

- TikTok is used as a propaganda channel for the elites;

- TikTok is (seen as) part of a Chinese threat to the West.

As can be seen in Figure 3, not all narratives are discussed at the same volume by the different conspiracy media. De Andere Krant is mostly focussed on how TikTok is censoring narratives that counter the mainstream, while BLCKBX TV focusses more on how elite organizations use TikTok as a propaganda channel. Sometimes multiple narratives are weaved together in one article/video. All media, however, connect TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda to a certain degree.

Figure 3: network of narratives and media. Numbers represent the amount of occurrences in the data

Below, I will pick apart each narrative by zooming in on one emblematic article. I will establish the narrating and narrated event in each case, analyse these narratives through the lens of intertextuality and indexicality, and draw up the ideological square to sum up the narrative that the case represents.

1. TikTok as censoring counternarratives

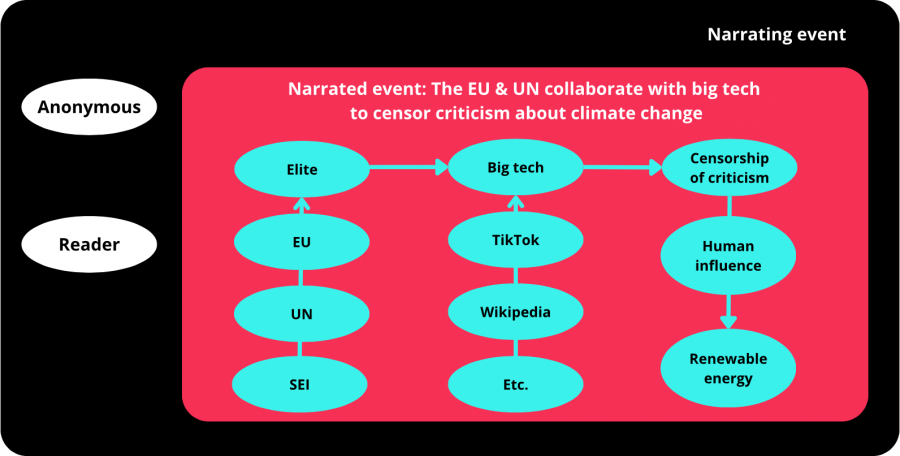

The first key narrative that is used to link TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda is about how TikTok is ‘censoring counternarratives’. The article “Klimaatcensuur wordt steeds scherper” (Climate censorship is getting ever tighter) by De Andere Krant focusses specifically on narratives countering the scientific consensus around climate change. The narrating event in this article plays out between the anonymous author of the article and the audience, while the narrated event is about how the EU and the UN collaborate with Big Tech to censor criticism about climate change.

In the article, two key groups are portrayed: the elite – consisting of the EU, the UN and its subsidiaries, and the SEI (Stockholm Environmental Institute) – and Big Tech – consisting of TikTok, Google, Wikipedia, Facebook, YouTube, Nu.nl and LinkedIn. These two groups are discussed as closely collaborating in order to censor criticism, specifically towards the ideas of human influence on climate change and of renewable energy sources as a solution to climate change. As shown below, Big Tech is framed in this collaboration as an ideological apparatus that enforces and reproduces the supremacy of the corrupt elite over the pure people.

Figure 4: narrating & narrated event case 1

The article is rife with explicit intertextuality, particularly in the form of quotes. Most of these quotes are derived from the elite organizations and Big Tech companies the article criticizes. For example, the author writes: “Melissa Fleming, spokesperson of the UN, talked about this on a congress: “We will be more proactive. We own the science […]. And the world should know this”” (De Andere Krant, 2023).

There is no hyperlink provided to where Fleming said this. In fact, there are no links to the sources of quotes anywhere in the article. However, we also find this quote in another article in the data, published by BLCKBX TV on 3 October 2022, where the quote is introduced as follows: “A high-ranking UN official admits to working together with big-tech companies”. The use of the word ‘admits’ is interesting here. It implies that the collaboration between the UN and Big Tech is a bad thing. It implies blame and guilt, rather than openness and transparency on the UN's part.

We find this fragment being framed this way across global conspiratorial, populist and new-right outlets. Knowing the statement by Fleming is understood by conspiracy media as proof that governments and Big Tech companies are in cahoots – a sort of gotcha-moment – explains why De Andere Krant refers to this specific quote in their article.

Quotes from elites are explicitly framed as proof of ‘censorship’

The intertextual links made through this and other quotes are thus not only pointing back to previous conspiratorial narratives. They also point back to the established narratives they criticize to act as ‘proof’ that justifies their critique. These discursive actions are reminiscent of what Francesca Tripodi has called ‘scriptural inference’, a practice common among Republican groups in America where they “critically interrogate media messages in the same way they approach the Bible. This […] bolsters their mistrust of mainstream media and supports their need to “fact check” the news.” (Tripodi, 2018). This ‘critical reading’ of ‘source material’ happens repeatedly throughout the article (and the rest of the data), with the author quoting TikTok press statements, government officials, and a report by the European Digital Media Observatory, among others.

These quotes are not presented as neutral, but are explicitly framed as proof of ‘censorship’. For example in the passage: “That censorship is getting more severe. In April TikTok announced that they will “more strictly enforce their policy regarding misinformation about climate change”” (De Andere Krant, 2023). No explicit explanation is given for why this mundane act of content moderation should be interpreted as censorship. But by repeatedly alternating between quoting acts of content moderation and referring to these acts as ‘censorship’, this hyperbole develops into common sense. Additionally, this gives conspiratorial media the opportunity to dodge the content moderation policies of digital platforms. Since they are 'just' quoting official sources as part of their scriptural inference, they can't be caught for spreading false information.

This frame is not new. Conspiracy theories about the media industry collaborating with political elites have a long history (too long to discuss here), including theories of predictive programming, the illuminati, the new world order, and cultural Marxism. By including TikTok’s efforts to mitigate misinformation about conspiracy theories on their platform in this article, the social media app is framed against this historical discourse of the media industry being a key player in manipulating the flow of information to benefit the elites.

Towards the end of the article by De Andere Krant, one source is referenced that is not part of the ‘source material’ that is criticized, but that is exactly in line with the historical conspiratorial narrative. The source is The Daily Sceptic, a British conspiracy medium: “According to Chris Morrison form the website Daily Sceptic, this is censorship” (De Andere Krant, 2023).

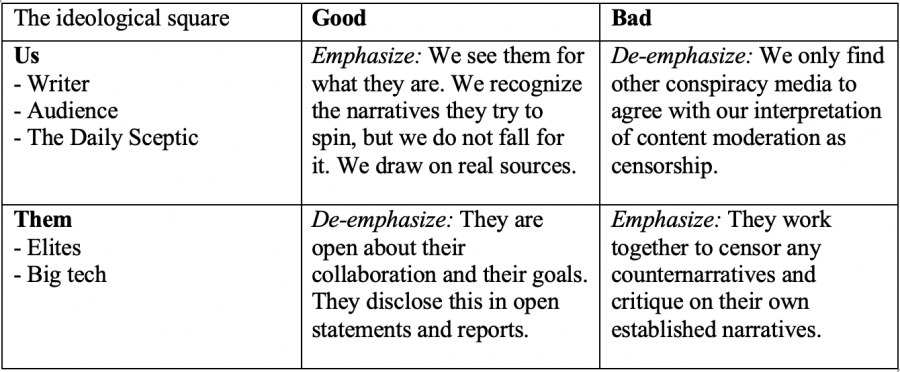

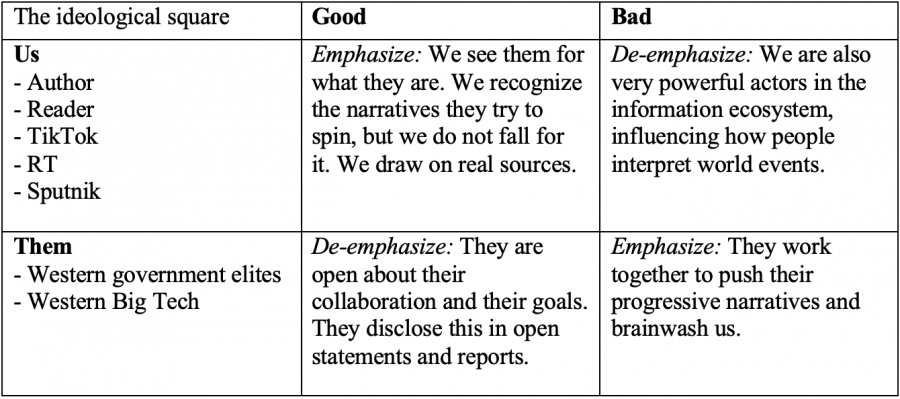

This article is emblematic of the narrative that TikTok is censoring counternarratives (in collaboration with elite governmental organizations), which is portrayed in a total of 5 articles in the data. We can summarize this narrative as a poplist conflict in group relations between ‘the people’ (Us) and ‘the elite’ (Them) that is at the root of conspiracy culture by plotting it in an ideological square (Van Dijk, 2011).

Table 2: ideological square case 1

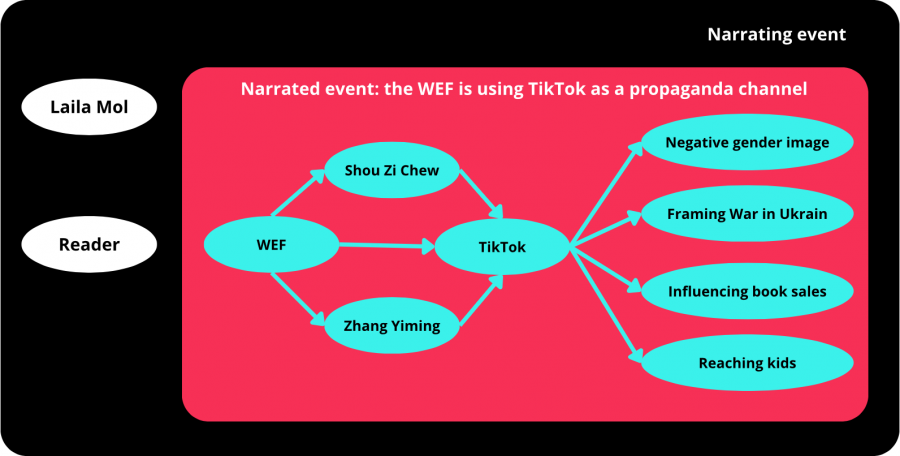

2. TikTok as propaganda channel

The second narrative that connects TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda is about how TikTok is used as a propaganda channel for the elite. When we compare it to the first narrative, they are two sides of the same coin. Censorship is about repressing certain narratives, while propaganda is about pushing specific narratives. In the grant struggle imagined in conspiracy culture, they are both expressions of the elite controlling the flow of information in order to obscure their nefarious actions, suppress dissent, and oppress ‘the people’.

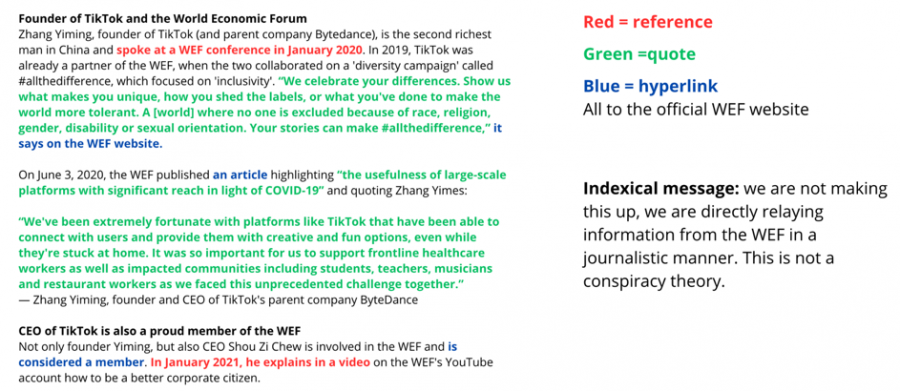

The propaganda side of the coin is strongly foregrounded in the article “TikTok is partner van het WEF en creëert trend: tienerjongens willen meisjes vermoorden op dates” (TikTok is partner of the WEF and creates trend: teenage boys want to kill girls on dates) by Laila Mol for Café Weltschmerz. The narrating event in this article plays out between Laila Mol and the reader. The narrated event is about how the World Economic Forum is using TikTok as a propaganda channel. Specifically, the article describes how the World Economic Forum is connected to TikTok (both directly and indirectly via founder Zhang Yiming and CEO Shou Zi Chew, both members of the WEF) and uses this connection to push a progressive agenda. According to the article, the WEF and TikTok work together to reach kids, demonize men by pushing femicide fantasy trends, decide how the war in Ukraine is framed by influencing the algorithm, and push progressive books via the BookTok trend.

Figure 5: narrating & narrated event case 2

The scriptural inference (Tripodi, 2018) found in the article by De Andere Krant is also present is this article by Café Weltschmerz. Most of the explicit intertextuality consists of quotes from and references to official statements by the World Economic Forum and TikTok management. Contrary to De Andere Krant, Café Weltschmerz does use hyperlinks to refer to the sources of their quotes. This hyperlinking practice implies that Café Weltschmerz is not just imagining a conspiracy theory, but that this conspiracy is actually happening out in the open.

And to be clear: the World Economic Forum and TikTok do collaborate. But we have to remember that the way conspiracy media frame this collaboration is deeply rooted in their imagined 'ideological' struggle. In their worldview, this collaboration is yet another example of the elite controlling the base and superstructure of society for their own benefit and the oppression of ‘the people’. But rather than engaging in an actual material analysis of the nature of the collaboration between the WEF and TikTok, Mol simply uses these different elements (the people, TikTok, WEF) to fill the populist discursive template is service of the worldview of the medium and its presumed audience. This worldview is confirmed by a big call for donations in the sidebar of the webpage. It reads: “The engine of Café Weltschmerz runs on your donation. Fight along with us for a free society”.

Figure 6: call for donations on Café Weltschmerz webpage

In this worldview, the World Economic Forum is given a central role. As a global organization that “engages the foremost political, business, cultural and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas” (World Economic Forum, n.d.), the WEF is the perfect antagonist in conspiratorial narratives. So it’s no surprise that The Forum has become a central node in the messy network of local and global conspiracy theories (Tulp, 2023). Café Weltschmerz even dedicated a content category on their website to the WEF.

This background tells us that by framing TikTok as the mouthpiece of the World Economic Forum, Café Weltschmerz also indirectly links the social media app to a wide range of other conspiracy theories. The implication is: if TikTok is helping the WEF push the books they want people to read, then what other propagandist messages are they spreading for the WEF?

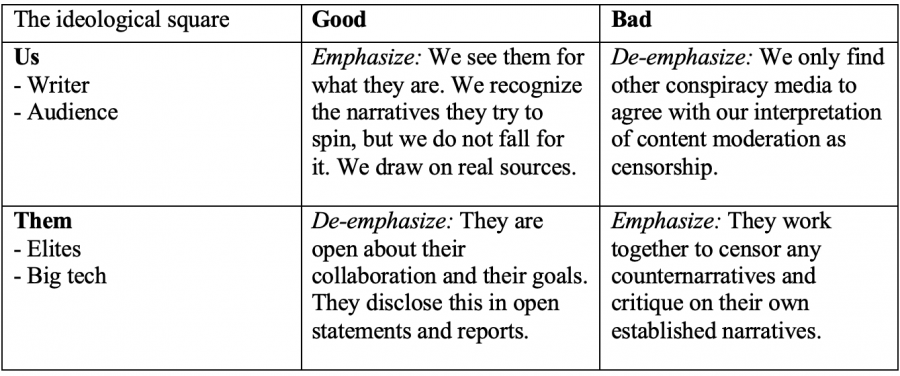

As censorship and propaganda are two sides of the same coin in the struggle imagined by conspiracy theorists, the ideological square (Van Dijk, 2011) we can draw up based on this second narrative is very similar to the first one. This article is representative of 5 other articles about TikTok as a propaganda channel.

Table 3: ideological square case 2

3. TikTok as Chinese threat

Where the first two narratives found in the data are closely connected, the third one distinctly deviates from them. The third narrative is about how TikTok is (seen as) part of a Chinese threat to the West. This narrative can also be found in abundance in mainstream media (e.g. Koenis, 2023; Hadero & Chan, 2023; Perigo, 2023). But in the conspiracy media looked at in this analysis, we again see this narrative being used to link TikTok to existing narratives of populist antagonism. Emblematic of this is the article “Hersenspoelen wordt het nieuwe normaal” (Brainwashing becomes the new normal) by Niburu.

The narrating event again plays out between an anonymous author and the reader. The narrating event, however, is rather complex, as can be seen in Figure 7. It describes how the Dutch government is brainwashing citizens by debunking and prebunking claims the author holds to be true, and by banning media coming from countries that oppose Western hegemony. Banned media that are explicitly mentioned are the Russian broadcasters Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik, as well as the ‘Chinese’ app TikTok. The Russian media were banned due to the pro-Russian propaganda they trafficked in the context of the war in Ukraine (NOS, 2022). TikTok was banned from the devices of state officials out of fear for Chinese espionage (NOS, 2023).

Figure 7: narrating & narrated event case 3

Contrary to the previous two narratives, this article does not frame TikTok as being in cahoots with governmental institutions together with other Big Tech companies. Rather, TikTok is framed as a platform opposing and threatening the government’s and Big Tech’s attempts at hegemony. According to the author, TikTok is not similar to other Big Tech companies. This contrast is pointed out by the inclusion of a tweet mentioning how Google is collaborating with the WEF and UN to “launch […] Prebunking, formally known as brainwashing” (@Symph0ny3 in Niburu, 2023), while TikTok is explicitly placed in opposition to this collaboration.

We still see TikTok being framed in a narrative of censorship, for example in the passage: “Off course we have the increasing censorship and it looks like Tik Tok [sic] will be forbidden in our country” (Niburu, 2023). But now TikTok is the subject of censorship, rather than the platform doing the censoring. According to the article, the banning of TikTok is part of “A continuous struggle of powerful people, controlled by powers in the background, to prevent people from thinking for themselves and forming their own opinion” (Niburu, 2023). If we follow the hyperlink placed under “powers in the background”, we come to another Niburu article which describes how the Illuminati and WEF are satanic, Jewish organizations orchestrating world events like puppet masters (Niburu, 2022).

TikTok becomes part of ‘Us’, instead of ‘Them’

As such, TikTok is not framed as part of the conglomerate of media and government elites, but placed outside of this circle and grouped together with dissenting media like RT, Sputnik, and, by implication, Niburu. In short, TikTok becomes part of ‘Us’, instead of ‘Them’. This diversion exemplifies the populist nature of the 'ideological' struggle imagined by conspiracy culture. TikTok can effortlessly be moved from 'the elite' to 'the people' based on the moral grounds of the author (dissenting information is good, fighting it is bad), since "it is the populists who construct the exact meanings of ‘the elite’ and ‘the people’" (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2012).

Though less explicit, this narrative is repeated two other times in the data. One episode of ‘BLCKBX news’ by BLCKBX TV (2023) includes a news item about Western governments banning TikTok for government officials. And an article by Eric van de Beek for De Andere Krant (2023) describes how the USA is pressuring other countries to ban TikTok alongside Huawei products.

Even though TikTok is still framed in the context of existing narratives of censorship and propaganda, this third narrative is distinctly different. It moves TikTok from the ‘Them’-row to the ‘Us’-row in the ideological square (Van Dijk, 2011). It also forces us to be more granular in who ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ are in the populist narrative of antagonism between ‘the elite’ and ‘the people’. Even though the attributions in the ideological square remain fairly similar, we have to tease apart governments and media companies/platforms that are against and in favor of ‘the people’ in this specific context.

Table 4: ideological square case 3

‘Professional journalism’

As these case studies show, conspiracy media use hyperbole, discursive connections, and historical frames to connect TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda. It is difficult to catch them ‘red handed’ spreading false information. But by critically interrogating how they talk/write about TikTok, we find they employ information (some true, some false) to reproduce the populist narrative of antagonism between 'the elite' and 'the people' in which conspiracy culture is rooted.

At the same time, these conspiracy media present themselves as ‘professional journalists’. On their about-pages, we find vivid descriptions of their journalistic valor. I have collected some snippets in Table 5 (Note: Niburu has no about-page, but their slogan has been included). All of them distance themselves from mainstream media. Café Weltschmerz is very explicit in doing so. The other three are more implicit. For example, when BLCKBX TV refers to themselves as an ‘honest’ platform, they imply that other media are dishonest. Being independent, critical and honest is the bare minimum for a news platform, you would say. But by explicating their own independence, critical stance and honesty, they also implicitly discredit other media. Apparently, these are not independent, not critical and not honest. This implication of ‘we are the real journalists’ is found throughout the conspiracy media landscape (Den Boer, 2022).

Table 5: self-descriptions of conspiracy media

Their presentation as ‘professional’ journalists is not limited to their about-pages, it is also present in their content. Going back to the article “TikTok is partner van het WEF en creëert trend: tienerjongens willen meisjes vermoorden op date” on Café Weltschmerz, the explicit and implicit intertextuality is reminiscent of journalistic openness about sources. At parts, the article includes few original ideas but almost completely consists of quotes and references to source material.

Above, I already pointed out the function of this scriptural inference (Tripodi, 2018) in confirming their conspiratorial worldview. But it has a second function: it indexes the journalistic identity they lay claim to. It is a form reminiscent of a journalistic register and the general ‘journalistic way of doing things’, which makes it difficult to discredit their claims without analysing the implicit (meta) narrative as I did above. Thus, by adopting this journalistic form, they can uphold their identity as ‘professional’ journalists while trafficking conspiratorial narratives.

Figure 8: explicit intertextuality in article by Café Weltschmerz

Conclusions

Conspiracy media present a distinct segment of conspiracy culture. They are neither crazy people spewing conspiracy theories on dark forums, nor influential individuals spreading outlandish conspiracy theories like David Icke or Alex Jones. Rather, they are, to varying degrees, professionalised news platforms mirroring the form factor of legitimate journalism. Their discourse, however, is rooted in a populist narrative of antagonism between ‘the elite’ and ‘the people’. In this narrative, both are empty signifiers that can be filled at will of the conspiracy theorists. Accordingly, we see that the conspiracy theorists do not engage in a critical analysis of power structures in society, but discursively construct a mythical 'elite' controlling a mythical 'people'. The case studies discussed in this article illustrate how conspiracy media employ current events like the controversies surrounding TikTok to confirm, substantiate and reproduce this narrative.

They deploy several discursive tactics to link TikTok to existing narratives of censorship and propaganda in the conspiracy milieu. We see them using hyperbole to frame mundane acts of content moderation as censorship and collaborations with governmental institutions as propaganda. We see them referring to official statements by elites as admissions of guilt, rather than as acts of openness and transparency. And we see them ‘critically’ interrogating this ‘source material’ in an effort to confirm their own world view.

In doing so, conspiracy media build on the historical backdrop of conspiracy theories involving the media as manipulators of information flows to paint a picture of TikTok as wholly involved in this populist narrative. And even though the configuration of the narratives spread by conspiracy media is not homogenous (sometimes TikTok is part of ‘The elite’ sometimes of ‘The people’), TikTok is consistently framed within this overarching narrative that defines conspiracy culture.

The implication of this is that we can hardly call out these relatively sophisticated conspiracy theorists as long as we remain at a surface level. As long as we take their texts at face value, they are indeed similar to the mainstream media. They do research, they critically engage with source material, and they hold power to account. If we truly want to understand conspiracy media and the methods they use to convincingly spread and mainstream their conspiracy theories, we have to move beyond simply fact-checking their claims to look at how every one of their stories – however true or false – implicitly contributes to their metanarrative of populist antagonism. Or as they see it themselves: their ideological struggle.

References

Althusser, L. (1970). Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.

Beckman, K. (2023, March 10). De Andere Krant - Brussel voert censuur sociale media op: Karel Beckman. De Andere Krant.

Blckbx. (2022a, July 13). VS schakelen TikTok influencers in om publiek te voorzien van juiste informatie. Blckbx.

Blckbx. (2022b, October 4). VN-functionaris op WEF-bijeenkomst: ‘De wetenschap is van ons.’ Blckbx.

Blckbx. (2022c, November 22). blckbx today #103: Docu “State of Control” over CBDC | Vaccinatiedrang neemt weer toe | “Poetins oorlog” [Video]. Blckbx.

Blckbx. (2023, April 6). blckbx news #7 | Maandag 3 april 2023 - 19:00 [Video]. Blckbx.

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A Critical Introduction. Ernst Klett Sprachen.

De Andere Krant. (2023, July 24). De Andere Krant - Klimaatcensuur wordt steeds scherper: Van de redactie.

Den Boer, R. N. (2022, April 6). How fake news website ‘De Nieuwe Media’ uses journalistic terminology. Diggit Magazine.

Gramsci, A. (2010). Prison notebooks.

Hadero, H., & Chan, K. (2023, March 25). TikTok’s CEO in Washington: Why app’s security risks keep raising fears | AP News. AP News.

Kircher, M. M. (2023, September 15). Beware the TikTok eavesdroppers. The New York Times.

Koenis, C. (2023, March 21). Waarom steeds meer landen TikTok verbieden voor overheidsmedewerkers. RTL Nieuws.

Kro-Ncrv. (2023, November 3). Tieners komen regelmatig video’s met misinformatie over het klimaat tegen op TikTok. KRO-NCRV.

Laclau, E (1977) Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory. London: New Left Books.

Mol, L. (2022, March 28). TikTok is partner van het WEF en creëert trend: tienerjongens willen meisjes vermoorden op dates. Café Weltschmerz.

Mudde, C. & Kaltwasser, C.R. (2012) Populism and (liberal) democracy: A framework for analysis. In: Mudde C, Rovira Kaltwasser C, eds. Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Navlakha, M. (2023, August 21). Which countries have banned TikTok? Mashable.

Niburu. (2022, October 1). Als je het nu nog niet ziet. . .

Niburu. (2023, February 16). Hersenspoelen wordt het nieuwe normaal.

NOS. (2021, July 8). Slob laat Omroep Zwart en ON toe tot bestel, maar zal scherp toezien op nepnieuws. NOS.

NOS. (2022, March 2). Russische staatsmedia geweerd uit EU, journalisten kritisch over “censuur.” NOS.

NOS. (2023, March 21). Kabinet verbiedt TikTok op werktelefoons van rijksambtenaren. NOS.

Penning, D. (2022, October 12). De Andere Krant - Klokkenluider onthult propagandacampagne Duitse regering rond Oekraïne-oorlog: Dide Penning. De Andere Krant.

Perrigo, B. (2023, March 23). What to know about the TikTok security concerns. Time.

Rubin, O., Bruggeman, L., & Steakin, W. (2021, January 22). QAnon emerges as recurring theme of criminal cases tied to US Capitol siege. ABC News.

St George, D. (2023, April 1). TikTok is addictive for many girls, especially those with depression. Washington Post.

Thompson, J. B. (1990). Ideology and modern culture: Critical Social Theory in the Era of Mass Communication.

Tripodi, F. (2018, May 16). Searching for alternative facts. Data & Society.

Trump, D. J. (2020, August 6). Executive Order on Addressing the Threat Posed by TikTok – The White House. The White House.

Tulp, S. (2023, January 17). As elites arrive in Davos, conspiracy theories thrive online | AP News. AP News.

Van De Beek, E. (2023, February 24). De Andere Krant - China roept wereld op: keer je af van de VS: Eric van de Beek. De Andere Krant.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2011). Discourse and Ideology.

Van Prooijen, J., & Douglas, K. M. (2017). Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Memory Studies, 10(3), 323–333.

Varis, P. (2019, November 10). Conspiracy theorising online. Diggit Magazine.

Wall Street Journal. (2021, July 21). Investigation: How TikTok’s algorithm figures out your deepest desires [Video]. WSJ.

Williamson, E., & Steel, E. (2023, March 18). Sandy Hook families are fighting Alex Jones and the bankruptcy system itself. The New York Times.

World Economic Forum. (n.d.). Our mission.

Zeng, J., & Schäfer, M. S. (2021). Conceptualizing “Dark Platforms”. COVID-19-Related Conspiracy Theories on 8Kun and Gab. Digital Journalism, 9(9), 1321–1343.