The (in)visible Poetry Museum in Amsterdam

In April 2017, the first Augmented Reality Museum was launched on the Museumplein in Amsterdam: The Poetry Museum. But how can this technological phenomenon influence the urban space?

The Poetry Museum

It is a rather ambiguous experience: standing on the Museumplein, moving my smartphone whilst looking at the several poems which appear on the screen. People who pass by apologize to me, assuming that they are walking through the pictures I am taking of my surroundings.

Instead, I am ‘visiting’ the Poetry Museum, a museum that merely exists through augmented reality. While standing in the midst of ‘real’ museums, which you do not have to unlock your telephone in order to see, it feels a bit unsettling to visit this one.

Besides that, I seem to be the only person visiting the museum that day, since I am the only one on the spot moving my smartphone through the air. But without the ability to see why others are using their phones and without the competence to see other visitors in the museum, I can never be sure.

I am ‘visiting’ the Poetry Museum, a museum that merely exists through augmented reality

This Poetry Museum merges the visible and the invisible, it intertwines the public and the private sphere and encourages smartphone usage in the urban space. The rise of both new technologies and digitalisation unavoidably affects the urban sphere, whereby a gadget such as a smartphone or tablet can transform the individual's role in the public realm.

This paper therefore aims to analyse whether and how this AR-museum can influence the public space. To do this, the application through which the Poetry Museum is visible will be analysed. I will place it in the context of augmented reality, its relation to the other museums on the Museumplein, and the privatization of the public space due to digitalisation. For this, the theory of Scott McQuire will be used, who wrote about the effect of screens on public space. With that, the ideas of Katherine S. Willis, who addresses digital publics and the privatisation of the public space, will be applied. By connecting these theories to the analysis of the Poetry Museum app, I aim to answer the question whether and how the AR Poetry Museum can influence the public space.

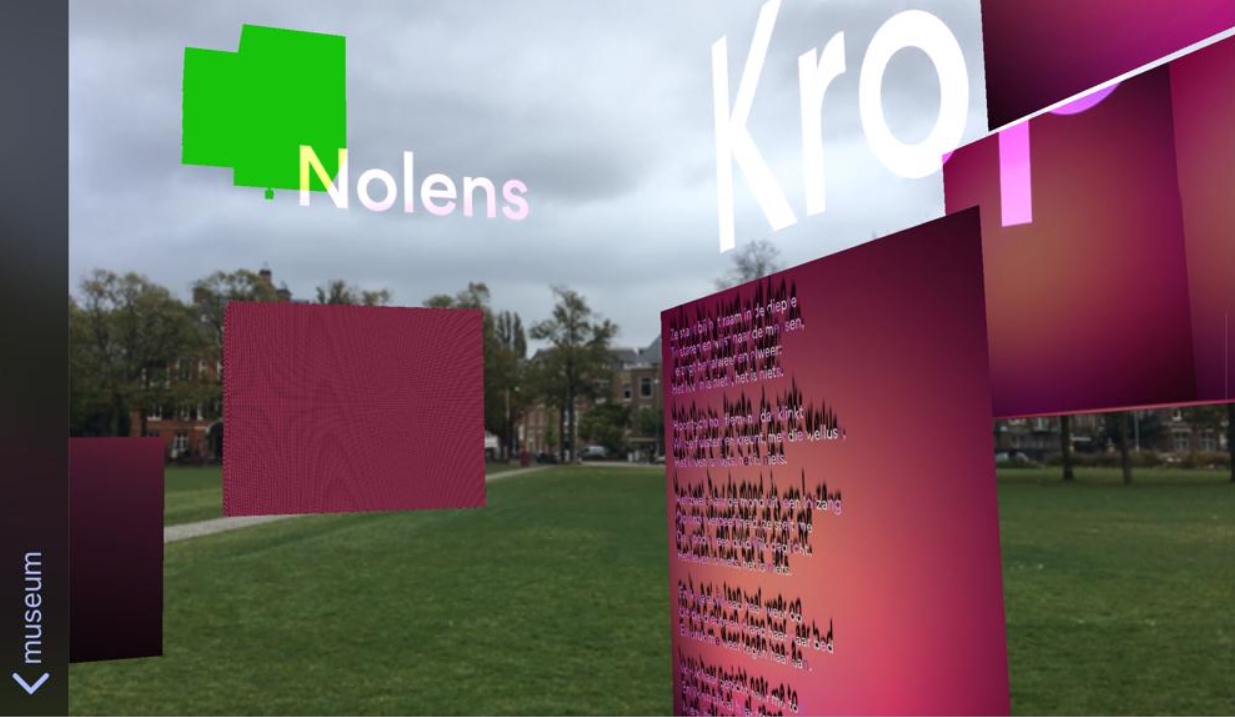

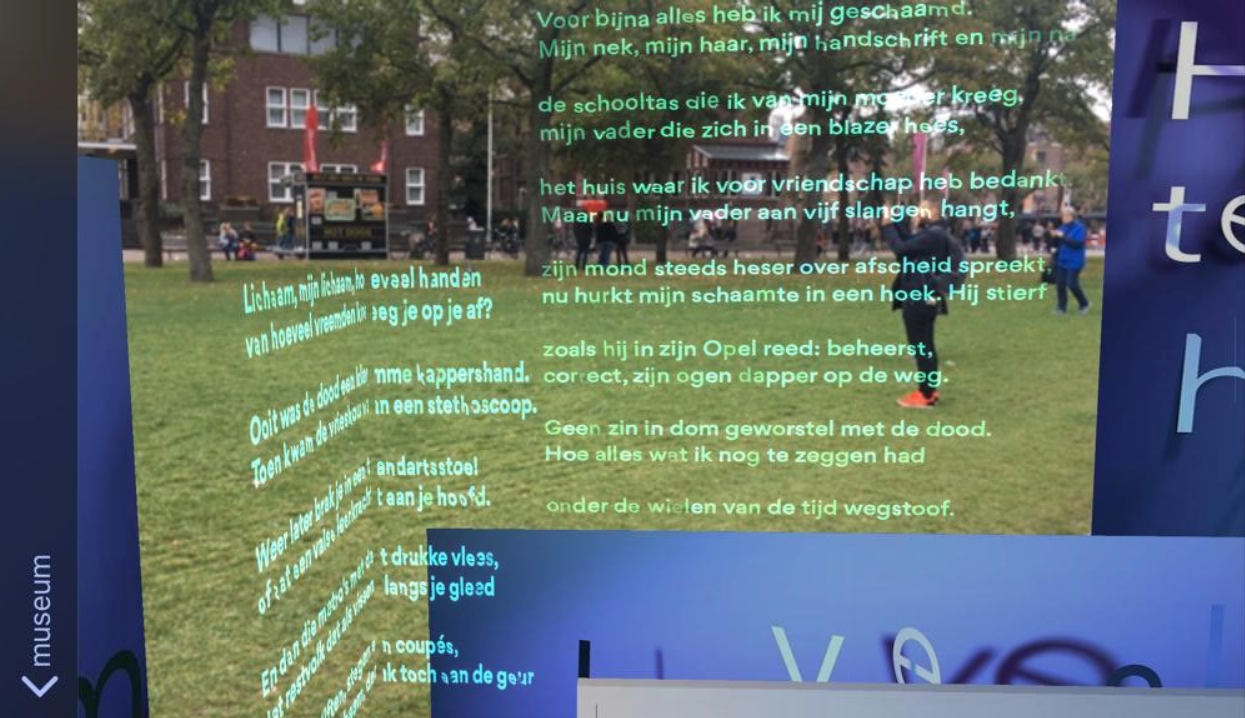

Picture of a part of the Poetry Museum.

The ever-changing public domain

Space is a term with no proportions. It consists of different dimensions which are produced by what it contains, while it also reconfigures and rearranges these contained elements (Quayson, 2014). It is not fixed and unchanging and depends upon what is bodily performed within it (Urry, 2004). Space is therefore ever-changing and from the 19th century on, urban development of cities has influenced the public sphere.

Scott McQuire explains in his book The Media City: Media, Architecture and Urban Space (2008) the contemporary interplay between media and public space. This means that new technologies and digitalisation have had an inevitable impact on the public space, which here is seen as a way of understanding how a society might hold potential for the collective (Willis, 2017). He starts his chapter on Performing Public Space with a timeline of how the urban landscape changed during the 19th century. With the emergence of vehicles, which created rapid movement, streets were adjusted to the dominant value of circulation (Sennet, 1994). With the rise of capitalism and Fordist mass consumption, city space welded into new social and political formations. After the Second World War, suburbanization was supported and people turned away from the street whereby they retreated to the private (McQuire, 2008).

These are three examples of how technologies and historical events impact urban streets. Another important influence was the emergence of the electronic screen. Whereas the first television screens led to people gathering in public spaces to watch television, the normalization of electronic screens then turned people to watch television in their own private sphere. The rise of the screens has led to a shift from public to private, which therefore inevitably influenced and transformed the contemporary urban space. Therefore, McQuire sees electronic media as the hinge between public and private life (McQuire, 2008).

This Poetry Museum merges the visible and the invisible, it intertwines the public and the private sphere and encourages smartphone-usage in the urban space

By the 1990s, devices such as the television and the telephone were primarily fixed. They were usually located close to the office or the home. By then, they already played an important part in the boundaries between private and public space (McQuire, 2008). In today’s society these technologies have become omnipresent, mobile, and extensible. They generate new possibilities for social interaction. With that, these mobile media have the potential to alter the dynamic of public interactions amongst crowds of erstwhile strangers. Where this mobile media can serve the individual consumer, whereby the electronic servant can fit his or her rational image of consumption, it can also serve the collective possibilities, by which mobile media enables people to act together in new ways (McQuire, 2008).

McQuire’s chapter on Public Performing Space acknowledges an important insight on the ever-changing urban space, which is that a change in urban space is inevitably linked to (the change of) the division between private and public. With that, it can be both the symptom and producer of social relations (Quayson, 2014). With the rise of new technologies such as the smartphone but also augmented reality, the borders between public, private, the individual, and the collective can and will shift. It also means that in order for an event, technology, or experience to influence or transform the urban space, it needs to be both interactive and linked to the domain of the private and the public. This will be kept in mind while looking at augmented reality in general, as well as the augmented reality museum.

Augmented Reality as a game-changing technology

Where the smartphone was not introduced to the consumer until 2011, augmented reality has its origins in the 1960s, when cinematographer Morton Heilig designed a motorcycle simulation with multi-sensory technology. AR takes digital or computer generated information, such as images, audio or video, and creators use these sensations by laying them over a real-time environment. T

he key feature of augmented reality is that the user is still able to see the real world around him, whereas virtual reality content simulates a whole different reality. Augmented reality supplements reality rather than replacing it. With that, it gives people the possibility to bring usable information into the visual spectrum without the limitations of time and space (Kipper & Rampolla, 2012).

Augmented reality supplements reality rather than replacing it

A smartphone gives the ability of personal mobility and spatial fluidity, therefore the use of it is no longer fixed in time and space. With the possibility to contact friends, family or colleagues from anywhere and at any time, social interaction on the streets changes. In addition, the smartphone and the Internet give the user the ability to search for everything online. Interaction in the public sphere therefore seems to become less and less important.

This immediately influences the public space. This idea is explained in Katherine S. Willis’ article ‘Netspaces: Space and Place in a Networked World’ (2017). She explains how the arrival of mobile phones and the Internet have led to the privatisation of the public space. With a smartphone in your hand, you no longer have to actively participate in the public realm. Social networking is now possible online, for which face-to-face interaction is no longer necessary. With the ability to create a social life online, this interaction shifted away from the public sphere (Willis, 2017).

Counter-arguments suggest that the public is very much a part of how people interact with their mobile phones, but that the public space is no longer merely the public sphere. Instead, it also consists of parochial spaces where people are involved in interpersonal networks that are located within communities (Willis, 2017). Willis sees this as evidence that media is changing the public space, but that it still allows the conditions for participation in the public sphere. With new, universally accessible public spheres opening up due to the internet, theorists have argued that these spaces merely contribute to so-called networked individualism, where people gather around shared interests, but where this equates more closely to the private sphere than the public realm. Here the focus lies on the individual in the public place.

The Poetry Museum

On the first of April, 2017, the Poetry Museum was ‘opened’ on the Museumplein in Amsterdam. From that day, visitors could download the app on their smartphone. The application shows the work of ten Dutch poets, such as Annie M.G. Schmidt and René Puthaar. [1] Writer Anna Enquist is the curator and she selected these ten poets, who each provided six poems. For all of them, a pavilion was created which together with the poems, shape unfinished architectural sentences.

Interaction in the public sphere seems to become less and less important. This immediately influences the public space

The Poetry Museum is an initiative of the collective called ‘International Silence’, which consists of two men, Twan Janssen and Johannes Verwoerd. They created the museum with the different pavilions, which can be seen by directing your phone at them on the Museumplein. Their aim was to squat Museumplein and to add a new cultural yet virtual destination. They therefore hope to reach not only a cultural elite but also people who don’t have that much experience with reading poetry. With that, they wish to create a museum for everybody, as they explain in an article for the Dutch daily newspaper 'Trouw'.

The idea of using augmented reality in or for a museum is not completely new. In 2010, the Museum of Modern Art in New York had the exhibition WeARinMoMA, where the artists created art through augmented reality. In the museum, 2D and 3D objects were exhibited, but they were only visible through the visitor’s smartphone.

In July 2017, the Art Gallery of Ontario opened an augmented reality exhibition as well, but with another approach: during their exhibition Reblink, historical artworks were transformed and given a modern update by using AR. Both exhibitions show the influence of technologies such as AR on the artwork and the museum. It adds a new dimension to the definition of art and the role of the museum. Here, the smartphone gives the visitor a certain power to decide which artworks they wish to see or transform, and which they do not. Augmented reality is used here to raise questions and consciousness as well as to lure people in to visit the museum.

Visiting the Poetry Museum @ Museumplein

Enquist tells us that she hopes that the Poetry Museum will attract all types of people, regardless of their knowledge of poetry, and she hopes to lure people in with the technique of AR. The application itself is easy to use, with only three options; info, museum and colophon. The museum then has the ten poets placed in a row and you click on the one which pavilion you wish to see. When you have chosen, you are placed ‘inside’ the museum, with the poems and the walls placed around you.

The museum is free to visit for everybody, as long as you speak Dutch and own a smartphone with the application. The museum has some clear differences with the other ‘real’ museums on the Museumplein: the Poetry Museum has no opening hours, no surveillance for touching the objects (which is simply impossible) and no strict rules on running or yelling in the museum. With that, the museum is no longer the traditional white cube: instead, there are some walls which are sometimes partly created with the poetry itself, as can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1. Picture of the Poetry Museum taken at the Museumplein, 19 October 2018.

Where on the one hand this makes it difficult for the visitor to read the poems, since the application does not allow you to watch the poems from a different viewpoint, it on the other hand creates the possibility for the curator and initiators to play with words, sentences and space. In addition, some poems have different typography. With the letters being part of the three-dimensional experience, the museum has a kind of theatrical effect. The artwork is here an instrument for the museum, rather than vice versa, which is the case for the ‘real’ museums on the Museumplein. With that, the focus of the experience in this museum lies not on the poetry, but is based on the potentials of AR.

Figure 1 shows a blurring of the distinctions between reality and the virtual. But with the Museumplein still being visible, an immersive experience is lost. With people passing by in real life and the impossibility to see other people visit the Poetry Museum, there is no full virtualization of the museum. Where virtualization is seldom total (Hjarvard, 2008), this border between real life and virtual influences the experience. The awareness of the presence of others influences the reading experience as well as the public realm (Willis, 2017): with the poems shown overlaying reality, you become more aware of the people walking behind the poems since they are a distracting moving background. Therefore, the space does not merely consist of private bubbles as Willis argued.

With the Museumplein still being visible, an immersive experience is lost

The museum negotiates the experience of reality by adding art to the visitor’s perspective. In the Poetry Museum, the augmented reality creates a new context in which the individual reader of the poems can not only observe, but also experience the ‘real’ Museumplein from a new angle since the virtual artworks overlay the tangible world. This can both add to the meaning the reader gives to the poem, as well as that he or she gives to the surroundings.

Additionally, it shows opportunities for augmented architecture, where things shown virtually can add another layer to the physical world. In crowded cities, it shows a new way to add to the urban space without physically losing space. It gives possibilities towards new forms of human presence, encounters and activities (Bishop, 2017).

Visiting the Poetry Museum @ Everywhere

Where the website of the Poetry Museum claims that the museum is only visible while standing on the Museumplein, I tried to open the application elsewhere, noticing that exactly the same museum is visible at every other place as well. This means that the museum is not really situated on the Museumplein and that people are no longer required to physically visit this location. This gives new insights but also opens critique on the project, since it thus can be wondered whether this museum can then add anything to the Museumplein.

The possibility to open the application elsewhere on the one hand adds to the initiators’ idea that they want to create a museum for everybody, since this might be the first museum which you can visit everywhere. The individual is then no longer bound in space. With that, the individual still sees the reality intertwine with the virtual, but this might be from his or her home. The public and private sphere therefore intertwine as well, but instead of it being a privatisation of the public space, it might be vice versa since the user can open a public space in his/her private realm.

It shows opportunities for augmented architecture, where things shown virtually can add another layer to the physical world

It is on the other hand interesting to see whether the museum can still influence the public sphere. Although the museum is not really located on the Museumplein, it might still lure people to that exact location. Visitors might visit the location anyway since the internet only provides information stating that you are required to visit the Museumplein in Amsterdam in order to see the poetry. When the visitor is standing on the Museumplein, surrounded by the big museums of Amsterdam, the experience might differ from the experience one has when visiting the museum from his or her home. Being surrounded by other museums whilst visiting this one can add to the idea of a cultural place, which can therefore influence the experience of visiting the Poetry Museum.

Can the Poetry Museum influence the public space?

The Poetry Museum is visible for the people consciously visiting the museum itself. Bystanders do not see/notice the museum as organized space. The distinction between the visibility and the invisibility of the museum shows complexity of the use and value of space. Where for some people the Poetry Museum adds extra meaning to the location, for others it is merely a space to pass by. There is a barrier between the people who know the museum and who do not, which influences their use and awareness of the public sphere.

In addition to that, there is a barrier between the people who own a smartphone and those who do not. Uneven access can here be seen as a problem for people to participate in this new phenomenon, whereby disconnection means the inability to engage (McQuire, 2008).

The smartphone-usage is an obligatory aspect. Hereby the use of a smartphone in the public sphere is encouraged by which the private and public space intertwine, which, as discussed above, can lead to the privatisation of the public space. The visit to the museum leads to a more individual experience since the use of a smartphone is merely individual.

In addition to that, the possibility to interact is completely left out. Where through the Internet and social media the user of a smartphone can connect with others, the application of the Poetry Museum leaves such interactivity out. The museum is merely based on the possibility to read the poetry. A virtual shared experience therefore is impossible and it is something that the initiators of the Poetry Museum acknowledge themselves:

‘You might see other museum visitors, but they may be visiting a completely different space. It’s like a silent disco for poetry.’ (Verwoerd, 2017)

The idea of the individual experience shines through. You might see other visitors in the real world but the experience of the museum will always be through the singular view of your own smartphone. Where you can have a totally different experience from others, it does not allow a kind of shared viewing or common experience, unless you discuss it afterwards. Since you are not in a private bubble but aware of your surroundings, you might find other visitors looking around you. Where it may not be a shared experience, the Poetry Museum can construct a new public concentrating this space (Willis, 2017). The app can bring people to the same physical place, where they have the opportunity to connect with each other. Here, the power again lies with the audience. They now not only have the power to decide what they wish to see, but can also take advantage of this newly created space. The audience can thus be merely an online spectator or decide to face-to-face interact with fellow visitors in the offline world. The change of the public sphere therefore relies on the participation of the visitors of the Poetry Museum.

Augmented reality, smartphones and the public sphere

In today’s society, the public and the private are inevitably intertwined. Gadgets such as the smartphone allow us to interact with others without the limitations of time and space. This influences the urban space, where face-to-face interaction seems to be no longer required and where new spaces can be added to the public space. McQuire has shown that in order to change the public space, interaction is mandatory. Here, Willis explains that today’s public realm is altered and that new networked spaces can be added to this, wherein the online space can be just as important as the offline. New technologies such as augmented reality have the ability to change this realm once again, intertwining the reality with the virtual.

The Poetry Museum combines the new possibilities of augmented reality with the possibilities of the smartphone. It first allows new ways of presenting art. With that, it enters the on-going discussion on the definition of art and the influence of new technologies. Second, it allows the individual to reshape the world through the smartphone. An invention such as this one can alter our perceptions and relationships with the urban space, due to the intertwining physical and virtual space. Further research using f.e. interviews can uncover how this influences the urban imaginary. The fact that the Poetry Museum can add another dimension to urban space, both the possibility to visit the museum from everywhere and the artwork as an instrument for the museum, are interesting topics for further research as well. Here the role of the museum and the artwork can be questioned, whereby the visibility inevitably influences the value of the artwork.

The Poetry Museum shows that offline participation and face-to-face interaction is a crucial aspect of public space

At the same time the individuality adds to the privatisation of the public realm, since visiting the museum seems to be merely an individual experience. Here the user is excluded from a common experience or shared view. Instead, every visitor experiences the museum differently. So where the public realm can be altered by communication technologies, the Poetry Museum seems one step away from that. Instead, it merely creates a new space, together with a new public that appears on the Museumplein. Without the possibility to communicate through the app, the influence on the public space seems rather limited. It is however not excluded.

The power here lies in the hands of the visitors to the museum. They are part of the public which is lured to the Museumplein, but the visitors are the ones who have to step away from the augmented reality in order to connect with the other visitors around them. For this form of augmented reality to influence the public sphere, it is unavoidably linked to the offline world. This thus shows that offline participation and face-to-face interaction is a crucial aspect of public space. Where smartphone usage in the public sphere is encouraged by this AR-museum, this paper therefore encourages people to actively participate in the public space by interacting with others and discussing the individual experiences. Here, the number of possibilities of augmented reality can merely be used to alter the public space if people decide to leave their private bubble and participate in offline encounters. Where a whole part of our society is performed online these days, the offline culture stays valuable.

Notes

[1] The ten Dutch poets are: Alfred Schaffer, Annie M.G. Schmidt, Elly de Waard, Eva Gerlach, Gerrit Kouwenaar, Ida Gerhardt, Leonard Nolens, Menno Wigman, Neeltje Maria Min and René Puthaar.

References

Hjarvard, S. (2008) ‘The Mediatization of Society: A Theory of the Media as Agents of Social and Cultural Change’ in: Nordicom Review, (29)2: 105-134.

Kaganskiy, J. (4 Oct. 2010) ‘Augmented Reality Art Takes Over The MoMA’, The Creators Project. Last retrieved on 28 Oct. 2018.

Kipper, G and Rampolla J. (2012) Augmented Reality: An Emerging Technologies Guide to AR. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

McQuire, S. (2008) Performing Public Space. In: The Media City, California: Sage.

Pronk, I. (29 March 2017) ‘Zestig gedichten in het museum zonder zalen’, Trouw. Last retrieved on 28 Oct. 2018.

Sennet, R. (1994) Moving bodies. In: Flesh and Stone, The Body and the City in Western Civilization, New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company.

Toft, T. (2016) What Urban Media Art can do. In: What Urban Media Art can do: Why When Where and How?, Stuttgart: Avedition.

Urry, J. (2004) Death in Venice. In: Sheller, M. and Urry, J. Tourism Mobility, Places to play, Places in Play, New York: Psychology Press.

Verwoerd, J. (2017) ‘Het Poëzie Museum’, Johannes Verwoerd Studio. Last retrieved on 28 Oct. 2018.

Wiercx, B. (12 July 2017) ‘Art Gallery of Ontario brengt klassieke kunst tot leven met augmented reality’, Faro. Last retrieved on 28 Oct. 2018.

Willis, K.S. (2017) Netspaces: Space and Place in a Networked World. In: What Urban Media Art can do: Why When Where and How?, Stuttgart: Avedition.

Quayson, A. (2014) Oxford Street, Accra, City Life and the Itineries of Transnationalism. London: Duke University Press.