"Meeting of Styles" and the online infrastructures of graffiti

Jan Blommaert argues that contemporary social and cultural phenomena, even though they look eminently local and offline, cannot be understood without taking the online dimensions into account.

Two simple points

This short research note intends to make two simple points, one general and one specific. The points are simple to the point of being trivial; yet, thinking them through has far-reaching but hitherto largely unexplored consequences. The general point is this: we cannot comprehend contemporary social and cultural phenomena, even if they look eminently local and “offline”, without catching their dialectical interactions with the worlds of “online” knowledge in which they are encased and through which they circulate and acquire their defining features. These features are “defining” in the sense that they have the capacity to transform the actor, the community and the practices involved. This point is broadly sociological, if you wish, and relates to the accuracy of our social and cultural imagination.

The second point is more specific and relates to ethnographic linguistic landscape analysis (ELLA; Blommaert & Maly 2015) as a sensitive method for investigating this complex contemporary social and cultural environment. It can be stated as follows: the semiotic landscapes we often tend to stereotype as purely locally and materially emplaced have acquired a major enabling online dimension, compelling us to realize that the sheer presence of offline semiotic landscapes must be related to their online infrastructures of production, circulation and uptake. Understanding such landscapes, thus, requires more than just inspection and decoding of the offline artefacts. This point is sociolinguistic (or socio-semiotic) and affects our analytical vocabulary for interpreting human signs and social (public) space.

Both points can, I suggest, be made in one move, by looking at one specific case. The case I shall employ for making these two points is graffiti. Or to be more precise, a worldwide series of graffiti events called Meeting of Styles (MOS), which for over a decade now has brought graffiti artists together at various places around the globe, for intensive event-like artistic and social communion (links to websites are given below). In August 2015, MOS settled down in Berchem, a district in Antwerp (Belgium), where over 2000 square meters of walls were decorated, turning the (previously run-down) urban area into a tourist attraction of considerable importance. While this is not the place to engage in detailed discussions of graffiti and its different scenes, some general but focused remarks may be useful.

From vandalism to art

A prominent Belgian graffiti artist also active in Berchem, Steve Locatelli, states on his website that “it is his goal to transform graffiti to a form of expression and thus to rid it of its stigma of vandalism attached to it.” Locatelli is one of these graffiti artists who managed to become a legitimate cultural entrepreneur. He runs a graffiti fashion and equipment shop in Antwerp, has an aesthetically sophisticated website, teaches workshops (also to senior citizens), paints murals as well as canvas, invites and accepts commissioned work and brings his art on show to galleries and museums. His works are not signed with the usual tags – cryptic graphic “signatures” hard to read for people outside the graffiti milieu – but written in clearly readable (and large) block letters. There is nothing anonymous or “sub”-cultural about his work, even if some of his murals would still be made in places considered “transgressive” or “intrusive”.

Locatelli testifies to the transformation of graffiti – or at least, part of the universe of graffiti – from a subversive, under-the-radar and illegitimate activity performed by artists preferring to remain in the shadow and move in a closed circle of fellow artists, to a legitimate and popularly recognized form of art making its way to the events-and-markets mainstream of the art industry. From rebellion to avant-garde, could be one way of summing up this transformation, from often severely repressed vandalism to an admired form of art, or from the margins to the center of the artistic “system”. And members of that mainstream can be used to neutralize the more rebellious members in the margins. Thus, Locatelli was invited by the Belgian railway company Infrabel in 2014 to “legitimately” paint part of the railway infrastructure in Berchem, otherwise infested with “illegal” graffiti – a commission that made newspaper headlines.

Figure 1: newspaper report on Locatelli’s mural, Berchem railway station. (11/01/2016)

It is important to understand that this transformation only touches part of the graffiti scene and coexists with other parts. We shall presently turn to the site of MOS 2015 in Berchem, and this site, we shall see, is in many ways exceptional and densely surrounded by more “transgressive” and “ordinary” graffiti such as that in figure 2, a picture taken just a few meters away from the MOS site.

Figure 2: “ordinary” graffiti, Berchem. © Frederik Blommaert 2016.

We notice the crisscrossing of tags and images, artists overpainting the work of others, and an emplacement in a nondescript, randomly chosen vacant public place – “vandalism” in the eyes of many. Tags can be found in the same area on garage doors, fences, electricity poles and public street furniture.

MOS in Berchem, August 2015

The transformation from vandalism to art involves several aspects;

- artists abandon anonymity and operate under clearly identifiable (even if pseudonymic) names, individually as well as collectively;

- they operate globally in a highly mobile scene of connected artists;

- they often (but not always) work in nonrandom, planned spaces and

- do so in a highly organized, event-like and “ordered” manner and

- in a quest for a broad art-loving public.

All of this relies on an online knowledge and communication infrastructure which we shall discuss in a moment.

Meeting of Styles – we can read, not by coincidence, on their website – emerged out of a one-off meeting of international graffiti artists at Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1997, and started in 2002. MOS self-defines as follows; observe the fit with the criteria given above:

“The “International Meeting of Styles” (MOS) is an international network of graffiti artists and aficionados that began in Wiesbaden, Germany in 2002. Brought together and inspired by their passion for graffiti, MOS aims to create a forum for the international art community to communicate, assemble and exchange ideas, works and skills, but also to support intercultural exchange. In the spirit of cooperation and promotion, since 2002 MOS has launched hundreds events in many countries across Europe, Russia, Asia and the Americas. These events have sponsored thousands of Graffiti-Artists from all over the world and throughout the years have attracted hundreds of thousands spectators, providing a focal point for urban street culture and graffiti art in order to reach a larger community. The “Meeting Of Styles” as its name says, is a meeting of styles, created to support the netting of the international art-community. It is not meant to be a forum only for classical and traditional Graffiti-Artists and -Writers, but a podium to present all different types of urban art! This is why we are open for all types and styles.” (http://www.meetingofstyles.com/faqs/)

The elaborate website of MOS contains announcements of planned meetings, an archive of past events (in the form of blogs), historical information on graffiti and other matters of interest, both intended for artists and for the public. The site is supported by corporate and nonprofit sponsors, as figure 3 makes clear.

Figure 3: MOS “recent partners”. Source: http://www.meetingofstyles.com/

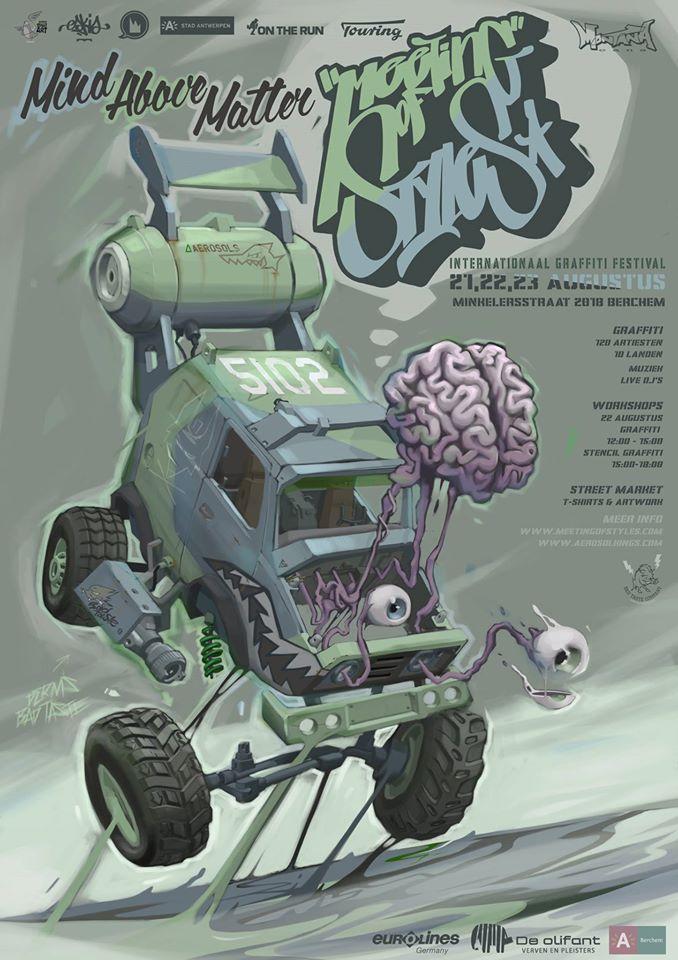

Individual events are sponsored as well. Figure 4 represents the official poster of the MOS-Antwerp 2015 event in Berchem; note the sponsors at the top and bottom of the poster and the specific, nonrandom location of the event. The format of this event is generic, it follows templates used equally in pop festivals and other large cultural performances.

Figure 4: MOS-Antwerp 2015 poster.

Source http://www.meetingofstyles.com/blog/antwerp-belgium-2/

The MOS-event is central to the performance; several individual artists and collectives also explicitly inscribe the event into their work, either in an epigraphic form, as in Figure 5, or in a more delicately integrated form as in Figure 6. Observe that these references to MOS point outward, away from the local space of emplacement and towards the global network within which it is situated.

Figure 5: MOS-epigram in graffiti, Berchem. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

Figure 6: MOS-motive in graffiti, Berchem. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

In Figure 5, we already saw that the artists’ names are written legibly in a standard typography. Artists do not hide behind a screen of “incrowd” literacy codes, they publish their names. Figure 7 shows more of this.

Figure 7: Artists’ names, Berchem. © Frederik Blommaert 2016.

And artists as well as “aficionados” leave their small name stickers together on a door in the site (Figure 8). They act as a community of named, identifiable and, as we shall see, “Googlable” artists.

Figure 8: Name stickers, MOS Antwerp 2015. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

In sharp contrast to the “transgressive” graffiti we saw in Figure 2, the works painted in the MOS-site are not overpainted, disfigured or tagged. Tags can be seen in adjacent places, sometimes facing the MOS-works, as if local artists pay their respects to the MOS-artists. The entire site remains in almost untouched artistic integrity – this is the collective work of an international artistic elite not hiding its names and proudly offering its work to thousands of spectators.

The online infrastructures of graffiti

This artistic elite is networked by means of the most advanced information and communication technology. The fact that they exist as an international consortium is due to the existence and intensive use of such instruments – see the MOS website – and the fact that MOS has become a global “brand” for artistically advanced graffiti is also largely due to the circulation of images, videos and blog texts on electronic online platforms. In fact, the entrance to the site is marked by a painting of the brand-and-event logo (Figure 9), accompanied by, in the left lower corner, three website addresses (Figure 10).

Figure 9: Brand-and-event logo MOS Antwerp 2015. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

Figure 10: Web addresses, MOS Antwerp 2015. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

Individual works, too, carry references to web addresses and social media profiles.

Figure 11: Web address “Disorderline.com”. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

Figure 12: Facebook profile address. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

These addresses, of course, lead us to elaborate websites and blogs where artists and collectives publicize their work, network with “friends” and followers, announce their future performances, comment on the work of others and communicate with their audiences. Their usage of this infrastructure is no different from that of most other users: they use these online instruments as a means for community formation (and therefore identity formation), as a learning environment for themselves and the members of their networks, and as a marketing and branding tool for their own work and that of the communities within which they situate it.

Online infrastructures enable the kinds of flexible, ad-how grouping of different networks into single moments or events, into “focused but diverse” communities that are typical for online life (Blommaert & Varis 2015). The internet enables otherwise loosely connected actors to convene in places such as the MOS-happenings. Figure 13 is a sticker of “Global Graffiti Burners”, a Facebook group operating as a graffiti network and offering a smartphone app to members, to keep in touch with community life. This network entered into the MOS-community during the happening.

Figure 13: Global Graffiti Burners. © Frederik Blommaert 2016.

And Figure 14 shows yet another vector shooting through this community-of-communities: commerce. Businesses also enter into the global event network and advertise their services, riding on the wave of admiration from an expanding audience for the artwork.

Figure 14: Homebase.nl advertisement sticker. © Frederik Blommaert 2016

Thus we see how the online infrastructures enable transformations such as those instantiated by MOS in the culture and economy of graffiti, reshaping the modes, formats and scales of activities, events and publics, the identities and communities of artists and audiences, the codes of interaction, exchange and networking, the hierarchies of celebrity and excellence in this field, and the intensity of community membership and group identity. The MOS website reports, for the second half of 2015 alone, events in El Salvador, Peru, Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico, the US, Germany, Belgium, Poland and Denmark. All of these events, scattered around the globe, gather a “core” of globally mobile artists alongside locally or regionally active ones, all connected by the spirit of MOS and each time jointly and collaboratively organized in a recognizable format – as a focused community that derives its cohesiveness from online exchange, interaction and knowledge sharing around a specific focus of activity.

Back to the two simple points

We owe to the likes of Howard Becker (1963) and Aaron Cicourel (1972) the fundamental insight that identity revolves around forms of communicated and exchanged knowledge that order and organize, as templates, social behavior and infuse it with moral, epistemic and political codes that need to be learned and competently displayed in order to gain access to (degrees of) membership of specific social groups – of “outsiders” in Howard Becker’s studies, and of “professionals” in Cicourel’s. These forms of knowledge construction, communication and exchange have since the beginning of the millennium been revolutionized by online infrastructures in ways anticipated by Manuel Castells (1996).

Castells, as we know, anticipated a massive change in the social system in which the traditional “thick” (Durkheimian) communities based on locality, nationality, race, ethnicity, class and religion would be gradually complemented (and perhaps sometimes replaced) by lighter, translocal and more volatile “networks” – communities that lacked the “thick” features of the older formations but would act as focused and cohesive formations nonetheless. And he saw the globalized electronic connectivity – nascent when he wrote these theses – as the tool by means of which such networks would emerge, gain currency and agency as hubs in which increasingly large segments of social life would be deployed, profoundly transforming social life in the process.

I believe the example developed here provides a case in point. There is a strong and widespread imagination of graffiti as an element of local urban subculture, often transgressive as we saw, and strongly rooted (like HipHop) in the local conditions of marginalization among young urban people. Graffiti itself – and I shall of course return to that below – looks eminently local, as its inscriptions occur in clearly defined material spaces in the here-and-now. To be sure (and I emphasize that earlier on), these features are there and remain intact. But MOS demonstrates how local graffiti artists can at the same time be involved in global activities, networked not just with friends from their Antwerp neighborhood but from Caracas, Houston or Copenhagen, and involved within this translocal network in highly focused forms of development and practice. So, while graffiti of course defines the visual atmosphere of specific local spaces, the ways in which these spaces are being defined is infused with influences from far away. A quick and superficial check of the artists who participated in the MOS-Berchem tells us that, apart from Belgian artists, works by German, British, American, Dutch, Israeli and German artists now decorate the local walls.

Sociologically, thus, maintaining conceptual distinctions between the “local” and the “global” becomes increasingly challenging, because, empirically, these different scales are intensely connected, and so effectively fused, by online infrastructures. These online infrastructures, we saw, enabled the artists to gradually relocate themselves from “vandalism” to “art” by deploying fora that won them entrance to new (online) public spaces in which new audiences could be addressed, in which new “artistic” identities could be constructed for themselves, and in which they could expand their activities to scale levels not accessible without such infrastructures. This, recall, was the first simple point I intended to establish.

The second simple point has, in the meantime, been established as well. There is in linguistic landscape studies a tendency to stereotype the objects of inquiry – signs in public space – to what we have seen above: local, offline, materially inscribed artefacts, which apparently also demand an analytical framework that refuses to transcend (or even interrogate) this superficial description. Evidently, such a method will fail to say anything substantially enlightening about the sociological point just established.

An ethnographically inspired linguistic landscape analysis (Blommaert & Maly 2015), by contrast, would insist on seeing such artefacts as traces of multimodal communicative practices within a sociopolitically structured field which is historically configured, begging questions about their origins and histories of production – including, of course, the bodies of knowledge employed in their production. And this is where a trivial fact becomes inescapable: offline local public signs often have their origins – and thus also an important part of their actual functions and meanings – elsewhere, in a translocal online world which has prepared them, tested them, debated them and circulated them long before they became locally (offline) emplaced on a wall or garage door in a specific neighborhood. And long after their local offline emplacement, these signs may lead a fertile life in this translocal online public space, in the form of an archive of linguistic landscapes that might, of course, in turn influence posterior signs.

A strictly localist interpretation of public signs such as graffiti may therefore fail to catch the point of such signs, both empirically and analytically. For its producers and users, such signs may not have a local function and meaning (ornot exclusively), but may, precisely, project them out of that specific space into another translocal world of cultural reference and social resonance, operating in and through entirely different public spaces than the one in which the sign is materially (offline) emplaced. We have seen in Figures 5 and 6 how references to MOS in works pointed away from the locality of emplacement towards a global network, from which the locality of emplacement derives at least part of its meaning and value, and by which its formal features – the planned, coordinated and nonrandom collective work that shaped the MOS event – are controlled. Likewise, the web and social media coordinates provided in works also situate the locally emplaced works in an entirely different translocal public space, connecting it to archives of work done elsewhere and to audiences in other timespace frames.

I propose not to take such details lightly. Because for analysts, it may be good to keep in mind, as we have seen, that the locality of a sign may be just one moment in an existence which is dispersed across space and time, and perhaps not always the most important moment. There, too, Castells’ fundamental imagery of a networked, polycentric and translocal world – online and offline – may be worth returning to. Linguistic landscapes do not only have the potential to inform us accurately and in great detail about the local social, cultural and political space; they also have the potential to inform us of vastly more.

As I said at the outset: the points made here are trivial and should, by now, be commonsense. Yet, there appears to be considerable reluctance to incorporate them into our fundamental sociological imagination and our methodological toolkit for investigating society. I hope that the exuberant clarity of the example I discussed here may help us overcome that reluctance.

References

Becker, H. (1963) Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. Glencoe: Free Press.

Blommaert, J. & Maly, I. (2015) Ethnographic Linguistic Landscape Analysis and Social Change: A Case Study. Tilburg papers in Culture Studies paper 100. https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/upload/6b650494-3bf9-4dd9-904a-5331a0b...

Blommaert, J. & Varis, P. (2015) Enoughness, Accent and Light Communities: Essays on Contemporary Iddentities. Tilburg papers in Culture Studies paper 139.https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/upload/5c7b6e63-e661-4147-a1e9-ca881ca...

Castells, M. (1996) The Rise of the Network Society. London: Blackwell.

Cicourel, A. (1972) Cognitive Sociology. Harmondsworth: Penguin Education.