The Kamergotchi-app: Constructing Digital Literacies with Arjen Lubach

The Dutch satirical news programme Zondag met Lubach has regularly influenced the public debate in the Netherlands and has even had some considerable real-life impact in the Dutch public sphere. This article analyses Lubach’s digital activism, to show how he constructs digital literacies with his digital initiatives.

Introducing Zondag met Lubach

From November 2014 until March 2021, hundreds of thousands of Dutch people tuned in every Sunday evening to watch Zondag met Lubach (ZML), a satirical news programme hosted by writer and comedian Arjen Lubach. As the VPRO – the broadcaster of the TV show – states; ZML offers seven days of satirically remixed news in 30 minutes. The show was a huge success, respectively ranking fifth and sixth in the top twenty-five most-watched TV programmes in the Netherlands in February and March 2021 (SKO, 2021a, 2017b). The show was discontinued in March 2021. However, due to its massive success, ZML was succeeded by De Avondshow met Arjen Lubach in February 2022 – a restyled version of ZML which is broadcasted from Monday through Thursday every week.

ZML deals with a range of different news items from the Netherlands and international environments through media, infographics, and investigative journalism. The show regularly succeeded in changing the (Dutch) political agenda and is praised for its ability to present difficult subjects, such as the TTIP (Boukes, 2019), in an understandable manner.

Lubach owes a big part of his public success to his calls to action, where he asks his audience to undertake action to ultimately effect change in society. In one of his episodes in 2017, Lubach mobilized his audience to fill out a petition against the Dutch “wiretap law” (in Dutch: sleepwet). Simply put, this law affected the data privacy of Dutch citizens. When the episode aired, the petition – which was initiated by a group of people outside of ZML – had 120.000 signatures. After the episode, the petition was signed more than 300.000 times within a week, necessitating the organisation of a referendum. This example, however, is only one of the many calls to action from Lubach.

The Cambridge Dictionary (n.d.) states that activism is “the use of direct and noticeable action to achieve a result, usually a political or social one.” According to this definition and taking Lubach’s frequent calls to action into account, he can be considered an activist. Previous research has shown that calls to action in satirical news programmes – such as ZML – are effective at mobilization and will encourage citizens to participate in easy political behaviours to influence key issue debates (Bode & Becker, 2018). Furthermore, research has shown how Lubach effectively uses satire in his activism to achieve considerable results for the public as well as the political agenda (Boukes, 2019; Boukes & Hameleers, 2020).

Digitally powered activism

Calls to action and satire are not the only tactics that Lubach deploys, though. Lubach customarily uses digital tools to mobilize support, raise awareness and effect change in the (Dutch) public sphere. For example, Lubach created the viral hashtag #hoedan, which criticised the abstract political programme of Dutch politician Geert Wilders. This hashtag and the corresponding ZML episode led to a decrease in support for Geert Wilders (Boukes & Hameleers, 2020).

Lubach also created the website vvdsteun.nl. This website has a so-called ‘support-poster generator’, which lets users generate fictional and meaningless support posters from the Dutch political party VVD. The website is a direct critique of the VVD’s idle expressions of support towards farmers. Perhaps Lubach’s most famous digital initiative was the internationally viral YouTube video “America First, The Netherlands Second,” which is essentially a ‘Donald Trump-parody’ and currently has twenty-nine million views on YouTube.

Lubach regularly uses digital tools in his activism

These examples are just a selection of Lubach’s digital initiatives. This article will investigate another digital initiative from ZML: the Kamergotchi-app, which was created in preparation for the Dutch elections in 2017. This app allowed users to take care of Dutch politicians to let citizens consider whom they wanted to vote for in the upcoming elections (Zondag met Lubach, 2017a).

This article will delve deeper into the Kamergotchi-app, Lubach’s digital activism and how he constructs digital literacies, following Belshaw’s model of digital literacies (2014). Therefore, this article tries to answer the question: “How does Arjen Lubach construct digital literacies with his digital initiatives in Zondag met Lubach?”

Elements of Digital Literacies

In 2014, Doug Belshaw published “The Essential Elements of Digital Literacies”. In this book, Belshaw states that traditional concepts of ‘digital literacy’ are problematic because they are highly ambiguous. This leads to a poor understanding of the concept and how it works in practice. He believes that literacy practices are inherently a social activity since they are used to communicate with each other. Therefore, Belshaw argues, digital literacies need to be taught in context. According to Belshaw, existing models of digital literacies do not work because they are taught as a singular skill rather than an encompassing contextual tool. Thus, Belshaw defines the eight essential elements of digital literacies. This model can be applied to different contexts and facilitates a better understanding of the concept of ‘digital literacies.’

The eight elements that Belshaw identified were: 1) cultural, 2) cognitive, 3) constructive, 4) communicative, 5) confident, 6) creative, 7) critical, and 8) civic (Belshaw, 2014), which I will elaborate on further in the analysis section of this article. These elements are tools which, taken together, will help someone construct a definition of digital literacies and therefore deepen their understanding of the concept.

The Kamergotchi-app

As shortly mentioned above, Lubach and his team developed the Kamergotchi-app in preparation for the elections of the Dutch government in 2017. The app is a playful take on the Japanese toy ‘Tamagotchi,’ which allowed users to take care of a virtual pet. Like the Tamagotchi toy, the Kamergotchi-app lets users take care of virtual pets, yet the pets in the Kamergotchi-app are Dutch politicians.

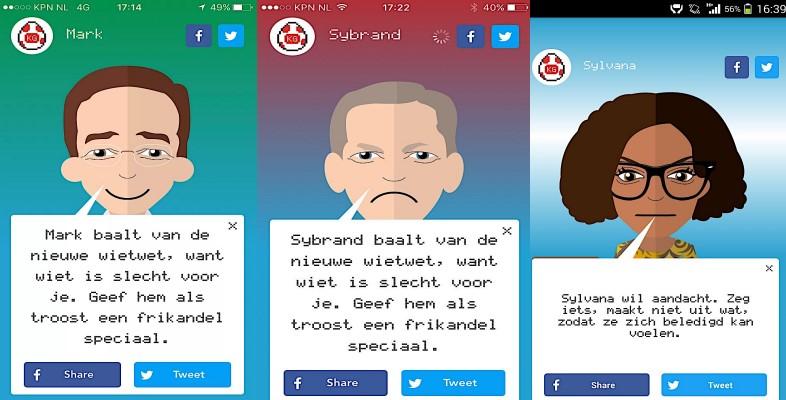

When users download the Kamergotchi-app, they can open an egg which contains the particular politician they will have to take care of. These politicians are randomly assigned; the user cannot choose which politician they would like to take care of. Users of the app can take care of their politicians by providing food, attention, and knowledge. If the Dutch politician is neglected, they will die. The user of the app then gets assigned another politician to take care of. The Kamergotchi-app responds to (political) news issues in the Netherlands. If an important political issue occurs, users will get a push notification that instructs users to give their politicians more attention or care (fig. 1).

Figure 1: The Kamergotchi-app push notifications

The app was available for download in the weeks preceding the 2017 elections and was immensely popular – with over 751.000 downloads (Zondag met Lubach, 2017b). On March 5th, 2017, about three weeks after its launch, ZML presented a poll that would predict how many seats each political party would get in the elections based on data collected through the app. Interestingly, this poll got rather close to predicting the actual result of the 2017 elections, as it predicted four out of the five parties that ultimately resulted at the top to garner the most seats in the parliament. After the elections had passed, the app was made unavailable in the App Store and Google Play store.

The Construction of Digital Literacies

“Let’s be honest… politics is also about the puppets. You just want to have a good feeling about the person you vote for, you want to be able to trust them. But then the question arises: for whom do you feel the most? Who would you like to take into your home, or prepare a plate of pasta for? This question… there should be an app for that.” (Zondag met Lubach, 2017a, 0:13).

When Lubach introduced the Kamergotchi-app in 2017, he presented it as a solution for undecided voters. According to him, a part of politics is also about the characters, or “puppets”, and there was yet no possible way to decide which character in politics one felt the best feeling towards. This train of thought led him to develop the Kamergotchi-app, a process in which multiple – if not all – of Belshaw’s elements of digital literacies are apparent.

The critical element, as defined by Belshaw (2014), involves thinking about one’s literacy practices, and how to structure digital “texts” to achieve the desired uptake. Lubach wanted to create something to help answer the question “Which politician do I feel the most for?”. Lubach has thus been critical in the assemblage of digital tools to reach this goal – which ultimately led to the development of the Kamergotchi-app.

Lubach and his team developed an app that was available for download and had all the functionalities they wished it to have. The development of such an app constitutes the cognitive element – which concerns navigating digital tools and understanding how they work. Furthermore, the development of the Kamergotchi-app also hinges on the constructive element. According to Belshaw (2014, p. 49):

“Developing this Constructive element of digital literacies involves knowing how and for what purposes content can be appropriated, reused, and remixed. It is as much about knowing how to put together other people’s work in new and interesting ways as it is about understanding the difference between the digital and physical worlds.”

The development of the Kamergotchi-app required Lubach and his team to understand the processes of app development and it asked them to have the ability to develop an app like Kamergotchi. However, while creating the app, Lubach also had to consider several contexts. That is to say, Lubach should have a relative understanding of Dutch politics, entertainment, and games. The cultural element of digital literacies refers to the ability to seamlessly navigate and understand the various digital cultures and contexts in the digital world. One is competent in this element if one can navigate between these different contexts and can combine them into one product. Since the Kamergotchi-app deals with various contexts, such as the ones mentioned above, it can be said that the cultural element of digital literacies is accounted for, too. Lastly, in the construction of the app, Lubach has also been creative – using digital technologies to achieve or create new things – and confident, which concerns the ability to confidently solve problems in digital environments.

Lubach demonstrates his competence in digital literacies by developing the Kamergotchi-app

Especially in his appropriation of the Tamagotchi game and Dutch politics, Lubach showed his competence in the cultural, creative, confident, and constructive elements. The development of the Kamergotchi-app required Lubach to understand these different contexts, pay respects to the different cultures, values and rules surrounding them, reappropriate material adequately and weave all of it together in a coherent story and app. Thus, the sole development of the Kamergotchi-app already accounts for six out of eight elements of digital literacies, namely critical and cognitive – both especially noticeable in the initial stages of the app’s development - but also constructive, cultural, creative, and confident.

Getting Somewhere: The Impact of the Kamergotchi-app

There are two elements yet to be dealt with: the communicative element and the civic element. The communicative element involves having the knowledge, skills and understanding to create a social object – or to communicate – in digital environments. In the case of the Kamergotchi-app, the communicative element can be found in two different instances. First, the communicative element manifests itself in the app; the app communicates certain messages about politicians and news issues through the push notifications mentioned earlier (fig. 2).

Figure 2: Messages about politicians in the Kamergotchi-app

Second, the communicative element is observable in the communication about the Kamergotchi-app. Lubach advertised the app in the corresponding ZML episode, but also on Twitter. The sheer number of downloads – 751.000 – shows that Lubach has been effectively communicating the Kamergotchi-app, thereby constituting the communicative element of digital literacies.

Finally, the civic element. According to Belshaw (2014, p. 57), the civic element is about “using digital environments to self-organise”. In other words, it is about using digital tools to effect change in society. Though there is no research if the app has considerably changed the 2017 election results, it did get a lot of attention in (Dutch) media. Users on Twitter have used the Kamergotchi-app, and the corresponding #kamergotchi hashtag, to share their personal opinions on politicians (fig. 3).

Figure 3: User expressing her disdain for politician Geert Wilders through the Kamergotchi-app.

Users have also used Twitter to share that they have decided to vote for their Kamergotchi-politician (fig. 4).

Figure 4: User sharing that she voted on her Kamergotchi-politician.

The popularity of the app and the activity of Twitter users concerning the Kamergotchi-app show that the app played a considerable role during the 2017 elections. People were talking about the app and sharing their opinions on Dutch politicians on social media, or even connecting their voting behaviour with their Kamergotchi-politician. Considering the influence that the Kamergotchi-app had on society during the elections, it can be said that the civic element of digital literacies is also accounted for.

Digital Literacies in Practice

According to Treré, digital activists are often pioneers when it comes to digital technologies. This is also true for Arjen Lubach, as this analysis of the Kamergotchi-app showed that Lubach and his team hold advanced levels of digital literacies.

Lubach owes a big part of his success to his calls to action and satire, which have regularly succeeded in mobilizing the public to effect change in the (Dutch) public sphere (Boukes, 2019; Boukes & Hameleers, 2020). However, this article has shown how Lubach’s digital literacies also contribute to his digital activism. Digital products, such as hashtags, websites, and certainly also apps, play a significant role in Lubach’s activism, and he regularly deploys them to mobilize his audience. By applying Belshaw’s (2014) model of digital literacies to the Kamergotchi-app, this article has shown how the Kamergotchi-app is not ‘just’ a funny game but is a well-thought-out digital product that, through Lubach’s digital literacies competences, achieves its desired effect in society.

It is important to note that the Kamergotchi-app is not available for download anymore, therefore my analysis relies solely on information that was available on the internet. Nevertheless, all elements of Belshaw’s (2014) model of digital literacies apply to the Kamergotchi-app. Therefore, this article still shows how digital literacies constitute a big part of Lubach’s digital activism, and how Belshaw’s model can be used to map digital literacies in practice.

References

Belshaw, D. (2014). The essential elements of digital literacies. Doug Belshaw.

Bode, L., & Becker, A. B. (2018). Go Fix It: Comedy as an Agent of Political Activation. Social Science Quarterly, 99(5), 1572–1584.

Boukes, M. (2019). Agenda-Setting With Satire: How Political Satire Increased TTIP’s Saliency on the Public, Media, and Political Agenda. Political Communication, 36(3), 426–451.

Boukes, M., & Hameleers, M. (2020). Shattering Populists’ Rhetoric with Satire at Elections Times: The Effect of Humorously Holding Populists Accountable for Their Lack of Solutions. Journal of Communication, 70(4), 574–597.

Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Activism. In Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved May 10, 2023

De Avondshow met Arjen Lubach, VPRO. (2017a, February 19). Kamergotchi - Zondag met Lubach (S06) [Video]. YouTube.

De Avondshow met Arjen Lubach, VPRO. (2017b, March 5). Kamergotchi peiling - Zondag met Lubach (S06) [Video]. YouTube.

Stichting Kijkonderzoek. (2021a, March 9). Persbericht Kijkcijfers TV Zendertotaal (Februari 2021) [Press release]. Retrieved May 9, 2023

Stichting Kijkonderzoek. (2021b, April 7). Persbericht Kijkcijfers TV Zendertotaal (Maart 2021) [Press release]. Retrieved May 9, 2023