DNA tests surveillance and privacy issues: AncestryDNA, 23andME, MyHeritage, or none at all?

Ancestry tests have conquered the market. DNA examination websites provide their customers with very simplified cultural instruction on how to reconnect with their identities and get profound self-knowledge in return (Rademacher & Kelly, 2019). With the price tag of around 100 USD for the test, an easy saliva-based procedure, and the third-party laboratory analysis, you will get the identity-recollecting job done for you.

Despite their wide promotion and millions of customers around the world, the service raises questions on the regulations behind it and how the business is set up. This article examines how DNA companies’ marketing branded and popularized self-tracking, and how this practice leads to privacy issues.

For this article, the communication of three major DNA companies websites was analyzed. The first one is Ancestry.com LLC, more specifically, its branch AncestryDNA: this company is the largest commercial service examining genealogical relationships, founded in 1996. 23andMe is a public firm specialized in biotechnology and personal genomics, with a 15-years history, and was the first one to popularize the tests for the mass audience through saliva sample analysis. MyHeritage has over 50 million users worldwide and specializes in European genealogy. The three companies were chosen because they are the most popular services among customers with a solid reputation in the market and expanding databases.

Marketing

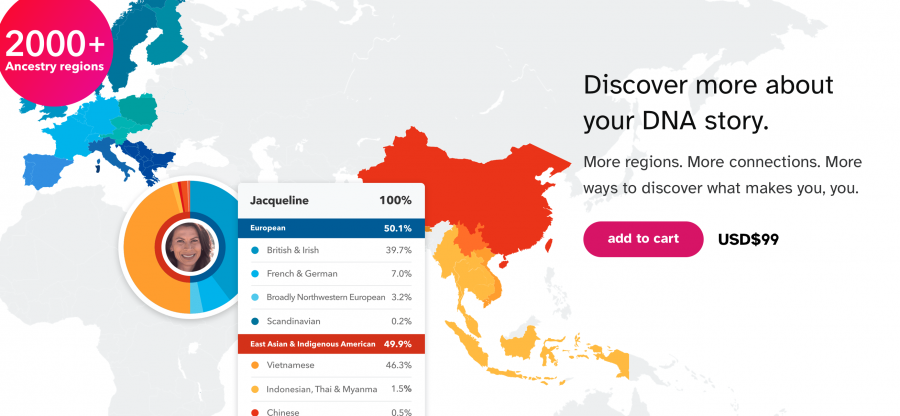

The coverage of the procedure presents it as an opportunity to explore true stories and incredible discoveries (Figure 1). This is done with the help of your accurate origin analysis (AncestryDNA, 2022a). The simple test promises “to reveal your unique ethnic background” (MyHeritage, 2022). The DNA services guarantee ethnicity estimates more precisely than ever before for you to uncover something new in a “unique, interactive experience” giving you “insightful geographic detail about your history” (AncestryDNA, 2022a). Additionally, the test promises to give users more of their ‘inside story’, whether physical or hidden traits, such as fitness and nutrient levels derived from your DNA information (AncestryDNA, 2022a). You are encouraged to learn, compare and share the discoveries of your personal traits (AncestryDNA, 2022a). As a bonus, you are offered to magnify your DNA results with around 100 million family trees and billions of records for more insights on your origin (AncestryDNA, 2022a).

Figure 1: 23andMe promises its customers the knowledge of “what makes you, you”.

The popularity of DNA tests is a conceptual mix of the awareness of global mobility and the romanticized marketing of ‘getting back to origins’. The way the services are presented, makes DNA information sound vital to users’ identity expression. However, as attractive as this idea might sound, "your DNA is not your culture" (Zhang, 2018) and it does not necessarily serve as a key to discover your true self. What the websites present is a trivialized scientific marketplace devaluing your genetic information to offer the myth of exploring your identity (Rademacher & Kelly, 2019).

The DNA tests operate on the fantasy of authenticity and customers’ uniqueness. There is a consistent taste regime buildup, or “a discursively constructed normative system that orchestrates practice in an aesthetically oriented culture of consumption” (Arsel & Bean, 2013). The taste regime of the self and finding one’s identity develops as a result of the “emergence of a new economic imperative” (Rademacher & Kelly, 2019). The process of sending a saliva sample to the laboratory and monitoring the website updates afterward is presented as a journey to one’s unique self and as an exclusive exercise of finding the truth.

Figure 2: AncestryDNA gives hope to put together the puzzle of users’ past.

As a result of the enticing site outline and convincing ‘explorer’ narrative (Figure 2), the DNA test companies propagate a shared understanding “of aesthetic order that shapes the ways people use objects” and attach meanings associated with the goods (Arsel & Bean, 2013). The service “seeks to reground consumption in practices that signify genuine independence from mass culture” and escaping the ordinary (Rademacher & Kelly, 2019; Meamber, 2015). What it leads to, is the emergent taste regime of discovering one’s true self, constructing a fertile ground for users’ consumerism.

Limited accessibility and underrepresentation

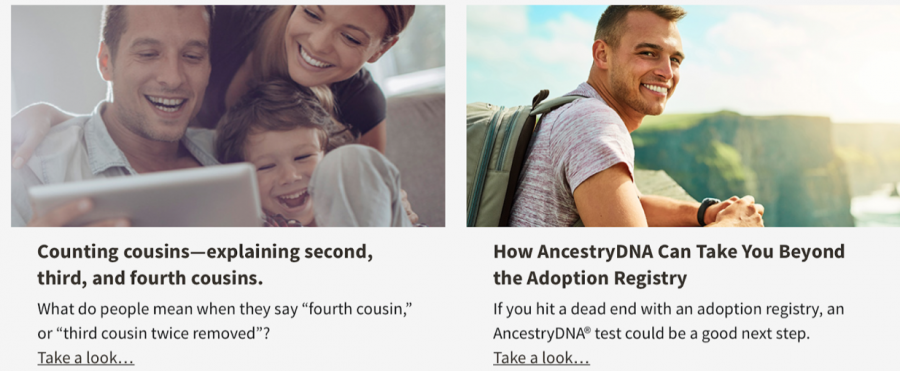

Figure 3: Young, white, happy, and (presumably) middle-class at the cover of AncestryDNA services.

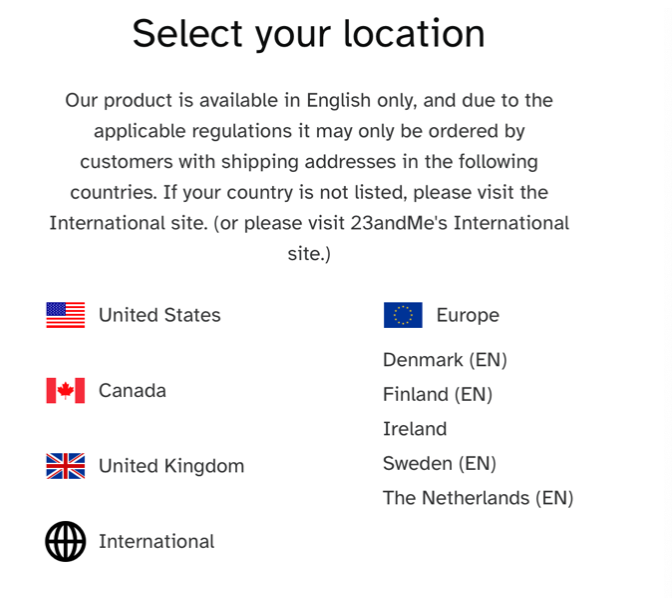

The companies try to mobilize a contemporary version of the idealized adventurers found in the archetypes and cultural contexts of the 19th-century (Rademacher & Kelly, 2019). The problem with this portrayal lies in its limited representation. The pictures promoting the service mostly feature young white happy people (Figure 3). The website of AncestryDNA is only available in English and Spanish, while 23andMe warns its users that their product is accessible in English as the only language (Figure 4). The key targeted audience is predominantly white and American, which explains the marketing appeal to discovering one’s ‘history’.

Figure 4: 23andMe also only offers its service to shipping addresses in selected ‘Western’ countries.

Only MyHeritage offers more languages and shipping options to its customers. Nevertheless, those are predominantly European languages that stand in line with the company’s focus region. The targeted audience remains rather ‘North-Western’ and white, with the price tag being rather pricey for the developing regions of the world.

The limited accessibility and underrepresentation issues are consistent throughout all three websites. However, this issue does not only lie in services' marketing. The companies' databases are also claimed to work best for white people, lacking racial inclusivity (Weise, 2018).

Surveillance and self-knowledge

Contemporary web platforms, wearable devices, and mobile applications offer a wide range of opportunities for their users to track every aspect of their lives (Zimdars, 2021). Ancestry websites are no exception in promising their users information on how DNA influences their facial features, taste, or smell (23andME, 2022). The DNA testing services create a new form of self-knowledge, central to one's 'true' identity. The mass popularized testing technology enhanced with heavy marketing triggers “a new culture of personal data” representing a new way in how individuals understand their bodies (Crawford, et al., 2015).

The discourse surrounding the ancestry tests revolves around the impression of revealing fundamental knowledge about its users. The ‘real’ body state is reflected with the help of “a radically new technology offering precise and unambiguous physical assessment” (Crawford, et al., 2015). Receiving one's general DNA information gives a seducing promise of self-knowledge helping create a “fitter, happier, more productive person” (Crawford, et al., 2015).

Figure 5: MyHeritage promises access to its clients from anywhere, anytime, on any device, bringing DNA tracking to the fairly domestic level.

However, the promotion of genetic self-surveillance is not new and has a historic predecessor. For instance, weight scales migrated from public spaces to every home. Such a development motivated repeated tracking of oneself and changed the meaning and the importance of the weight measuring procedure (Crawford, et al., 2015). Similarly, commercial DNA tests have brought genetic information from fancy secluded laboratories to their clients’ devices across the globe. The connection between data and self-improvement made in the early 20th century is still topical to this day (Crawford, et al., 2015). The accessibility and simplicity of the offered procedures leave society wondering, whetheryou ‘really’ know yourself if you do not know where you might have come from. The ancestry tests have brought genetic knowledge to the domestic environment, and this can develop further into this type of examination becoming even more accessible and common among the general population (Figure 5).

The companies' databases work best for white people, lacking racial inclusivity

The problem arises when profound self-knowledge is used by applying normative control (Crawford, et al., 2015), i.e. when you give up sensitive information for the companies to compare “your test results with millions of other test takers who have also opted into the feature and gives you a list of people you share DNA with” (AncestryDNA, 2022b). As a result, the user gets the measurements influenced by subjective standards that might be misleading to their personal conditions. The results one gets on their traits present a linear relationship without taking into account users’ agency in adjusting their lifestyle and habits for health and physical improvement.

Additionally, the data estimates might not always be accurate (Crawford, et al., 2015): customers of different ancestry tested repeatedly receive opposite results because of human error and varying over-, or underrepresented databases (O’Rourke, 2017), to cite but few. Despite being promoted as an ultimate source of self-knowledge, the DNA test can still be far from getting it right.

Privacy

Genetic information is extremely valuable for the pharmaceutical industry, for insurance companies, research, and other third parties. That is why ancestry companies aim at collecting ever more data from their customers,like the additional service of building a complete family tree uncovering users’ family histories (MyHeritage, 2022). To lure the information, the DNA firms offer ‘best deals’ to trick customers and motivate them to submit their own and their family tree data to expand services’ databases (Figure 6).

Figure 6: MyHeritage promising the ‘best value’ deal offering users to fill in more personal data.

Getting self-knowledge with the help of ancestry tests is not as much about knowing yourself, but also making yourself known to others (Crawford, et al., 2015). Relying on the services indefinitely securing the information is not completely realistic. When using commercial DNA testing services, one should remember the possible privacy risks that come along.

Users’ information disclosure works on multiple levels. Firstly, the sites offer a ‘social media experience with a genetic twist’ (AncestryDNA, 2022a). The function makes you visible to others, for instance to possible distant relatives you do not know of, as a default option unless you specifically change it in the settings. Users can also provide other personal information, such as their photo, address, phone number, work history, education, nationalities, languages spoken, family members, height and weight, etc (McGowan, 2021). Just as with other social networks, users should be aware of how much of themselves they are ready to disclose with people they don’t know, especially when it comes to sensitive and genetic data.

Secondly, it is not completely transparent how information gets stored, despite the websites' promising security. Data breaches and leakages are still possible. For instance, in 2018, MyHeritage’s security issue leaked the data of 92 million users (Motherboard, 2018). The information ended up being for sale on the dark web.

Thirdly, the services guarantee no disclosure of “individual-level information with any third party without your explicit consent” (23andMe, 2022). The sites do not specify how any non-individual level data, for instance about family trees, gets treated. Despite the companies promising a safe and private experience, the ways terms of service are worded call for loopholes. The companies do not “provide your information or results to employers or health insurance companies” (23andMe, 2022), however, life insurance, disability insurance, long-term care insurance, and pharmaceutical companies are not mentioned (McGowan, 2021). 23andMe has shared genetic information with pharmaceutical companies, and GlaxoSmithKline has exclusive rights to use the data for drug development. MyHeritage claims they have never sold or licensed personal data, but they still use third-party trackers on their website (McGowan, 2021).

Just as with other social networks, users should be aware of how much of themselves they are ready to disclose with the people they don’t know, especially when it comes to sensitive and genetic data

Additionally, the companies disclose the databases as a part of their mission “to advance research related to the study of human genetics, genealogy, anthropology, and health” (AncestryDNA, 2022). The data gets shared often “regardless of your consent status” to “third-party research partners” (23andMe, 2022). The firms do not specify the types of studies the data is used for. When it comes to science, getting a huge pool of DNA samples can open horizons both for good and bad. For instance, one would hope the research is only done on cancer prevention medicine, but as the worst-case scenario, it might be targeting a specific genome in a mass destruction weapon.

Finally, all of the ancestry DNA firms have a history of providing their data to law enforcement organizations in solving crimes. The companies warn their users that they are obliged to comply with law orders in helping certain investigations. Even if you have never used commercial DNA companies, you can still be tracked through one of your relatives who have.

To take or not to take?

Collecting genetic information is a profitable business. DNA tests are promoted by commercial firms as a way to find users' identities and a way to get to know about their unique traits. Such a representation motivates users to get deeper into the yet uncovered aspect of their self-knowledge. However, this appears problematic as your DNA sample gets compared to millions of others in the normalized 'do it for your real self' procedure that goes along with several privacy issues.

Overall, the DNA services reflect a larger pattern of quantification and datafication of every spare part of our lives. The fact that such a procedure is so available to us nowadays, and will only be more accessible in the future, is a historical pattern of developing self-knowledge speeded up by contemporary logistic opportunities and digitalization.

Even if you have never used commercial DNA companies, you can still be tracked through one of your relatives who have

As a general recommendation, it could be said that users should be careful whom they entrust their sensitive data. One should pose a question: is it really my deep desire or is my willingness to find my DNA composition a result of a carefully set up marketing strategy? Customers to these services should evaluate whether sending their samples is worth risking their privacy. However, if they make this choice regardless, they should attentively research and compare terms of use and choose the option best-suited for them, since only 9% of customers read the contract conditions (Wisgard, 2019). One should also consider whether using the social network option afterward is beneficial or whether it attracts unnecessary strangers who can see their personal information.

References

AncestryDNA. (2022a). Ancestry Privacy Center.

AncestryDNA. (2022b). Genealogy: Putting Together a Puzzle of Your Past.

Arsel, Z., Bean, J. (2013). Taste Regimes and Market-Mediated Practice. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5): 899–917, https://doi.org/10.1086/666595

Crawford, K., Lingel, J. & Karppi, T., (2015). Our metrics, ourselves: A hundred years of self-tracking from the weight scale to the wrist wearable device. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4-5): 479-496.

McGowan, E. (2021). Here's what your MyHeritage DNA testing kit reveals about you. Avast.

Meamber, L. A. (2015). Commentary on learning to talk like an (urban) woodsman: An artistic intervention. Consumption Markets & Culture, 18(6): 559—568.

Motherboard. (2018). Hacked: 92 Million Account Details for DNA Testing Service MyHeritage. Vice.

MyHeritage. (2022). Discover your family story.

O'Rourke, T. (2018). How accurate are in-home DNA tests like Ancestry, 23andMe?. WCPO.

Rademacher, M. A. (2019). Constructing Lumbersexuality: Marketing an Emergent Masculine Taste Regime. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 43(1): 25–46.

Weise, E. (2018). Looking for your roots? For Asians, blacks and Latinos, DNA tests don't tell whole story. USA Today.

Wisgard, A. (2019). 23andMe sell your data – should you be worried?. Dnatestingchoice.com.

Zhang, S. (2018). Your DNA Is Not Your Culture. The Atlantic.

Zimdars, M. (2021). The Self-Surveillance Failures of Wearable Communication. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 45(1): 24–44.

23andMe. (2022). How it Works.