Everything you need to know about otaku

“Otaku (おたく/オタク) is a Japanese term for people with obsessive interests, particularly in anime and manga” (Wikipedia). I believe this is the most simplified meaning of the term that can be found online. "Otaku” is a word that hides more than you might think.

This article first discusses its literal meaning, its Japanese meaning, and its outside-of-Japan meaning. Then I will go on by investigating the workings of international online groups of otaku. The last part deals with relevant content on three social media platforms, namely: Youtube, Instagram, and Facebook.

What is otaku?

Although the Japanese word “otaku” is widely associated with the meanings of “nerd” or “geek”, it literally means “your home”. According to Morikawa Kaichiro (2012), otaku was used to indicate geeks by Nakamori Akio, in an essay titled “A Study of Otaku”. This essay appeared in the 1983 edition of Manga Burikko, an erotic manga magazine.

“When you think about it, these types aren’t just manga fans, and they aren‘t a species whose only habitat is Comic Market. Those creatures who line up outside the theatre the day before the opening of some anime film? […] Or the fans who go early in the morning to secure a spot at an autograph fair for some teenybopper idol? We have lots of names for people like this –crazies, fanatics, introverts— but none of them quite do the trick. In my opinion, we still don’t have an appropriate term that somehow covers both these particular variations and the general phenomenon of this character type. And so, for reasons entirely of my own making, I shall dub them otaku.” (Nakamori, 1983)

The term Nakamori coined is taken from the second-person pronoun that anime fans back then used in conversations among themselves. In the 1980s, anime fans (but not only) begun to mingle at events like Comic Market, striking up conversations with strangers who shared the same tastes. They used the word “otaku” to say “you” when talking among themselves, and Nakamori transformed this distinctive pronoun to a derisive term.

Morikawa Kaichiro (2012) further identifies the culture as distinctly Japanese: a product of the school system and society. Firstly, Japanese schools have clubs (extra-curricular activities), where students' interests are recognized and nurtured, catering to the interests of otaku.

Secondly, the vertical structure of Japanese society identifies the value of individuals by their success. Those unable to succeed socially focus on their interests, often into adulthood. With their lifestyle centered on those interests, they further the creation of the otaku culture.

"Japanese otaku" vs "international otaku"

Manga and anime are maybe the best known Japanese cultural export products, and with their globalization, otaku also became a global phenomenon. This globalization did not produce a homogenous meaning. On the contrary, there is a difference between who is defined (and defines himself) “otaku” in Japan, and who is defined as such outside of Japan.

The dark side of the word’s definition refers to the level of the obsessive interest reaching extreme levels.

On the one hand, in Japan otaku is a person with any kind of obsessive interest (one can be a train otaku, a Disney otaku, a fish otaku and so on). On the other hand, outside of Japan the concept of otaku is not well-known, only within a niche group of people interested in manga and anime. These are Japanese cultural products, and for that reason, these people are likely to come across the Japanese word "otaku" and use it.

Figure 1: Otaku meme

To put it simply, in Japan a stereotypical otaku is a creepy person without a social life. And his or her room would look like the one in Figure 1. This pejorative connotation started with the 1989 "Otaku Murderer" case. Afterwards, people began to associate otaku with dangerous people. This gave a derogatory meaning to the fandom, from which it has not fully recovered.

It also has to do with the specific interests of a person that, in times, can be extremely odd (as in the case of otaku wanting to marry body pillows). As Bennett (2011) writes for CNN's blog, Geek Out!: "The dark side of the word’s definition refers to the level of the obsessive interest reaching extreme levels." Patrick W. Galbraith, writer of "An Otaku Encyclopedia" and researcher of contemporary Japanese culture at the University of Tokyo, says that often otaku are "people who are perceived to let hobbies get in the way of taking on 'adult' roles and responsibilities at work and home."

However, some studies show that the connotations of otaku have been changing over the years, especially among young people. There is a research study in Japan (2013) that shows that the term has become less negative, and an increasing number of people now self-identify as otaku, both in Japan and elsewhere. In fact, among the 137,734 people involved, 42.2% self-identified as otaku, 62% of which were teens. There is also a YouTube video interview from That Japanese Man Yuta (2013) that supports the idea that there is a great number of Japanese youngsters who identify as otaku.

Otaku are a deviant and niched cultural group, because they don’t follow socially imposed and accepted norms. They have a particular set of perspectives about what the world is like and how to deal with it. But as Becker (1973) writes, whether an act is deviant or not depends on how others react to it. That is, deviance is created by society. The same behavior may be an infraction of the rules at one time and not another; it may be an infraction for one group but not for another. Clearly, labeling involves other people. In Becker's words, “social groups create deviance by making the rules whose infraction constitutes deviance” and people apply those rules to particular people, labeling them outsiders.

Otaku's authenticity discourse

Being an otaku is part of the construction of one’s identity. Otaku has authenticity discourses (discursive orientations towards sets of features that are seen as emblematic of particular identities). Many videos on Youtube address the matter of authenticity. To make my point, I will discuss one particular video.

As the title “How to spot a fake otaku” suggests, the creator of the video discusses what differentiates a real otaku from a fake one. (Bear in mind that, here, the meaning of otaku strictly means a person interested in anime and manga.) The video makes 3 points:

- You are a fake otaku when you lack in knowledge (you have not seen enough anime).

- You are a fake otaku when you immediately praise an anime, when in reality you don’t have enough knowledge to make comparisons.

- You are a real otaku when you deny being one (commonly, out of shame).

The first point is linked to the concept discussed by Becker (1973) under the name of “career". As in any group, the more you know, the more you are likely to be accepted by the group you want to be part of, and you will be regarded as an expert. It also has to do with the concept of 'enoughness'. As Blommaert & Varis (2015) explain "one has to ‘have’ enough of the emblematic features in order to be ratified as an authentic member of an identity category". It is about having a small (but enough) number of recognizable items: "Enough" to produce a recognizable identity as an authentic member of the category, as the objects people have reflect an attempt to construct authenticity.

In the third point, we recognize that the author of the video sees himself as a master, determining the boundaries of what it is to be a real otaku.

YouTube, screenshot, comment section

Figure 2: Screenshot of YouTube comment section

As we can deduce from the comment section (Figure 2), the creator of the video is considered a role model. He proudly states being an otaku, and some followers seek to be recognized by him as otaku.

The first example is of someone asking “Am I Otaku?”, followed by a long list of anime the person has watched (a reaction to point number 1 made in the video). Many more write about having spotted fake otaku. Somebody else manages to react to all the points made, saying “you just watched an anime, and you tell everyone that you are an otaku? I watched more than 90 anime […] and I know that in front of good-looking guys you say that you don't know what anime is”. But there are also disagreements, as someone comments: “what I believe makes a true otaku is their passion for anime or manga (doesn’t matter how many you have watched)”.

Online communities

As I mentioned above, with the globalization of anime and manga, otaku also became a global phenomenon. Internet, with its global reach and increasing availability, strongly contributes to globalization. In this case, internet enabled the spread and connection among the cultural group. As pointed out by Blommaert and Varis (2015), "Internet has shaped an unprecedented degree of integration". Increasing integration means that social and cultural phenomena are new in scope, intensity, and degree.

Despite the controversial connotation of otaku, Japanese people make billions off the otaku market

Blommaert and Varis (2015) also write that “aspects of human life belonging to the private sphere are intertwined with consumption behavior”. What we do is we strive towards maximum recognizability, and we get anxious when we fear not being recognized. Recognizability is about getting all the details in line with the normative expectations of a group.

Norms, as pointed out by Becker (1973) apply to subcultural groups the same way they apply to mainstream social groups. Recognizability is tightly connected to consumption because a commodity is loaded with sets of personality features. As a consequence, the purchase of a commodity is a way of buying features of personality (contained in the commodity).

Specifically, acts of consumption are, always and instantly, acts of identity. The paradox is that we want to be (and we see ourselves as) authentic, but truth is, we need a level of conformity in order to be recognizable by others. So while striving to be recognizable, we create particular details in relation to the norms we have to submit to (Blommaert & Varis, 2015).

Consumption plays a huge role in constructing the identity of otaku, as otaku spend lots of money on action figures, manga and posters of their favorite anime. So, despite the controversial connotation of otaku, Japanese people make billions off the otaku market (Bennett, 2011).

Otaku goods can be found online and offline. Offline, Japan’s Akihabara district in Tokyo, is best known: it is a popular district where both natives and tourists shop. The countless anime-themed conventions that take place every year around the word are also highly profitable. As for the online sphere, there are countless otaku merchandise stores, also very easy to find (OtakuHouse being one among many others).

Fandoms and light communities

There are groups that emerge out of the complex life projects. Light communities are groups that are diverse but focused on one thing at the same time (Blommaert & Varis, 2015). During the time in which people converge around a shared focus, a strong sense of group membership is created. This is relevant since we spend much time in such ephemeral forms of groupness. Fandoms illustrate just that: it is an online environment where people who share the same interest can find each other on social media, even if for a brief period of time.

Otaku, in the narrow sense of the word (only lovers of anime and manga), have many infrastructures of identity that help globalize their culture: online websites such as My Anime List and groups on Facebook or Instagram help nurture the interest.

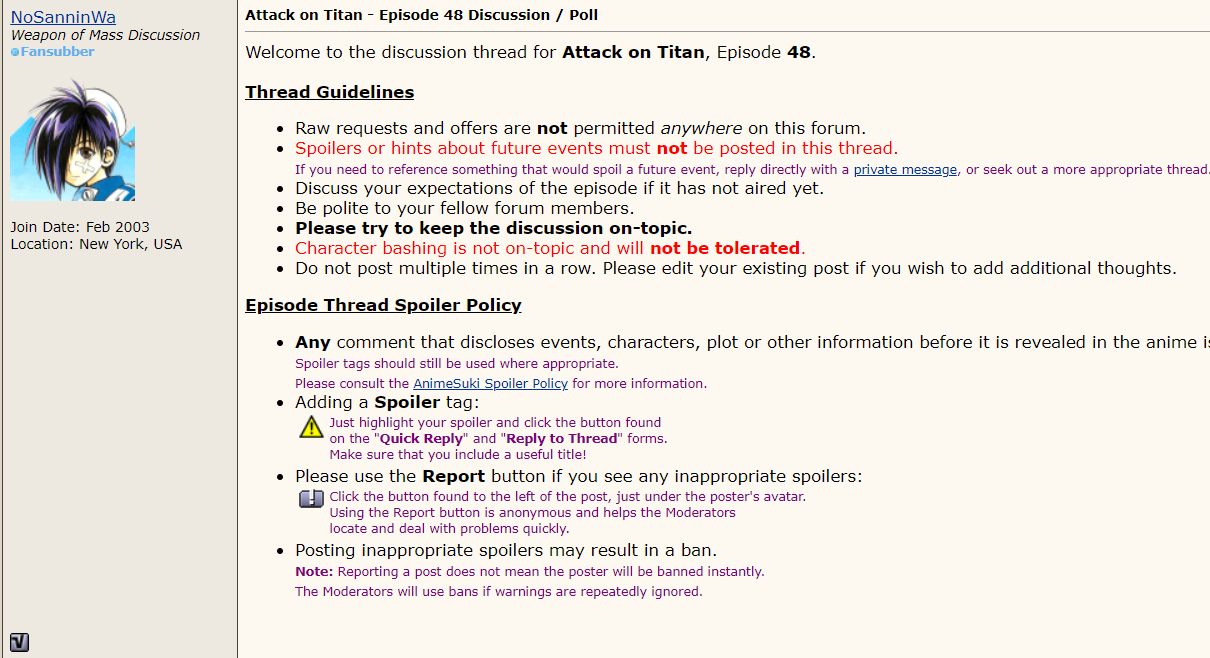

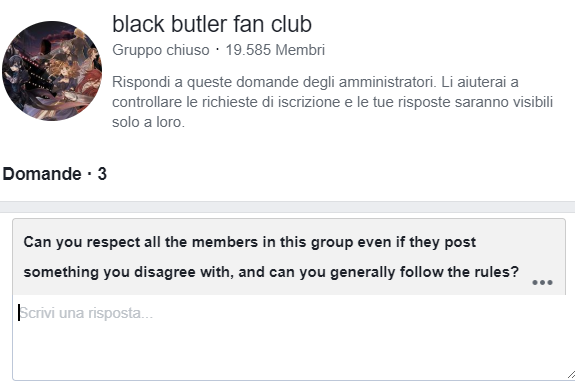

On these websites, people can come together to discuss their favorite anime in a very detailed manner. Discussions can be about one episode of a series at a time, as it happens on AnimeSuki Forum or Naruto Italian Forum. There is also a hierarchy of users: the administrators usually set some rules for the proper use of the platform (Figures 3 and 4) The most popular ones are: no spoiler, and keep the discussion within the theme selected.

AnimeSuki Forum, screenshot, guidelines

Figure3: Sreenshot of AnimeSuki Forum guidelines

Facebook, screenshot, black butler fan club

Figure 4: Screenshot of black butler fan club on Facebook

On these forums, the accounts are anonymous. Profile pictures often include characters from anime and manga, and in some cases there is no profile picture at all.

Clearly, social media play a crucial role in spreading the otaku culture, and more generally, internet is one of the primary instruments in the globalization process of otaku culture. For example, a search under the name of "otaku" will lead you to more than 100 Facebook pages.

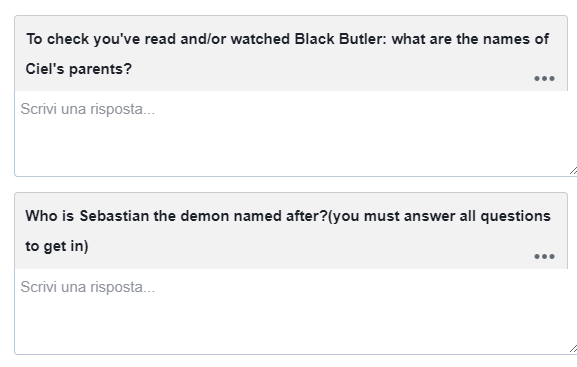

During my research on Facebook, I came across only a few closed groups, one of which is black butler fan club. Before I could become a member, I was asked to answer two questions about the anime Black Butler (Figure 5). After submitting my answers, my request was accepted in a matter of minutes.

Facebook, screenshot, black butler fan club

Facebook, screenshot, black butler fan club

Figure 5: Screenshot of black butler fan club (Facebook)

Anime and manga are now so famous that local versions of fandoms are not an exception. This is why we can say that otaku culture is translocal, layered and polycentric: it has spread outside of the local Japanese context and there are different layers of identification, plus there are many centers (local national otaku groups and global otaku groups) (Maly & Varis, 2015).

Despite this, it is clear that local groups have more difficulty growing, as the small numbers of participants show (e.g. BlackButlerItalia, NarutoItalia in Italy). We can conclude that when English is the main language, a community has more chances of becoming popular, as English is a lingua franca on a global scale, i.e. a language that is adopted as a common language between speakers whose native languages are different (Oxford Dictionaries).

Memes as phatic communication

Popularity also has to do with the content shared, and social media groups primarily prefer memes, followed by fan art, and cosplay pictures (as opposed to episode by episode discussions of anime, which is usually dealt with on forums).

Facebook, screenshot, Tokyo Otaku Mode

Figure 6: Screenshot of Facebook group Tokyo Otaku Mode

The reason for the popularity of memes has to do with some of the characteristics described by Blommaert and Varis (2015). Memes can be understood as phatic communication. They are built on (and build) groups of people, where particular versions of reality are taken for granted.

In fact, memes only make sense within a community with shared (implicit) assumptions. In other words, the understanding of memes relies on presuppositions. Memes also combine fun with facts, making them extremely shareable and likeable. That is an essential feature for a page's growth in popularity, because nowadays we massively rely on quantification when making choices. As a consequence, the more shares one manages to get the better.

Instagram, screenshot, otaku__italia

Figure 7: Screenshot of otaku__italia (Instagram)

The instagram account shown in Figure 7 otaku__italia (a case of translocal otaku culture) is an emblematic example of how social media pages heavily rely on memes to get their likes.

The memes are about different topics, but they all use pictures of animes. Some are about student-life, some about specific animes and some are based on Italian popular culture. They all have different implicit assumptions. For example, one that addresses students reads "when during an exam you whisper to your friend and the teacher catches you". Another one addresses an anime: "when you are Eren Jaeger and your friends tell you it's useless to want to kill every giant".

The latter meme implies you know who Eren Jaeger is in the first place. Somebody who has watched Attack of Titans would know that Eren is the name of the main character. Clearly, for somebody who has never watched Attack of Titans, this meme is not funny. Another one addresses popular Italian culture, as it mentions Don Matteo, which is an Italian television series.

Otaku as a social group

In conclusion, after introducing the controversial definition of otaku, we saw why otaku is a niched culture. It is the result of the globalization of a local culture (Japanese anime). With it, otaku also globalized. Through this globalization, otaku acquired a new meaning (not a freak but a dedicated fan). It was also de-globalized (as in the case of Italian otaku). The result is a niched, layered, and polycentric culture. A so-called light community, or micro population.

In this article, we have addressed the matter of the local and global phenomenon of the group and its behavior online. We have seen that Internet plays a crucial role in spreading knowledge about otaku. Moreover, the niche culture comes with rules, norms and authenticity discourses. To be recognized as a real otaku, you have to accommodate shared norms, such as being knowledgeable and recognizable by buying anime merchandise. We have analyzed the characteristics of otaku social media pages and the relevance of memes within this community.

References

Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: Study in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Bennett C (2011) Otaku: Is it a dirty word?.

Blommaert, J. & Varis, P. (2015). Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies nr. 139.

Hoffman M. (2005) Otaku harassed as sex-crime fears mount.

Maly, I. & Varis, P. (2015). The 21st-century hipster: On micro-populations in times of superdiversity. European Journal of Cultural Studies, p. 1–17. United Kingdom: Sage.

Mynavi News (2013) 自分のことを「オタク」と認識してる人10代は62%、70代は23% [62% of Teens identify as "otaku", as opposed to 23% of those aged 70].

Phillips, W. (2016). This is why we can't have nice things: mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. The origins and evolution of subcultural trolling. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Kaichiro M (2012). おたく/Otaku/Geek.

Katayama L (2009) Love in 2-D.

That Japanese Man Yuta (2015). Are Otaku(Nerds) Uncool? (Japanese Interview) [Youtube].

The Anime Man (2013). How To Spot A Fake Otaku [YouTube].

Web Japan (2005) Geek spending power. Otaku Business Gives Japan's Economy a Lift.

Wikipedia (n.d.), Otaku, retrieved on 2 December 2018.