“He’s a 10 But…” Discussing Relationship Discourse Online

Social Media trends on platforms such as TikTok have widely changed our dating discourse. The most popular narratives promoted by these formats fundamentally transform our view of potential partners.

He’s a 10 but he only wears Flipflops: the Trend

“He’s a 10 but he only wears Flipflops” is one of the statements TikTok creator Eugene Litman presents his interviewee with. The response “-4” comes from a young woman, not further identified. These types of street interviews pose rapid-fire questions with little reaction time for the participants to answer. Uploaded to TikTok they offer a variety of opinions at once with minimal questioning from the audience or the people involved. The “He’s a 10 but…” format is one of the most popular sets of questions these street interviewers ask their participants. The initial statement in this case refers to the looks of a potential partner. This scale usually goes from 1-10, 10 being the most desirable a person could be. The added “but” indicates a potentially fatal flaw, something that would keep the participant from pursuing the “imagined 10”. In many cases, this usually points out a behavioural or physicial characteristic made to disrupt the illusion of a perfect partner. In Eugene Litman’s case, these “but”-statements become very specific, from “he only communicates through Snapchat” to “he claps when the plane lands”. None of these instances are a detriment to a successful relationship, yet they cause a rapid decline in the “rating” given by the young women in these interviews. Trends involving “rating games” have become increasingly popular on platforms such as TikTok. To understand contemporary perceptions of dating this paper aims to explore the superficial characteristics of dating-related discourse online. Specifically, I will put into focus how gamification in digital media leads to the reinforcement of these prejudices.

Methods

Studying trends on social media of the late 2010s such as TikTok requires a deeper look into the potential formats and sentiments that precede the current ones. Using the concept of intertextuality thus becomes crucial in understanding the emergence and significance of “He’s a 10 but...” interviews and the connection they have to previous formats and mindsets in dating culture. As described by Johnstone (2018), intertextuality sees the connection a current piece of media has to media of the past and its potential to shape the future. A “new” social media trend is never entirely new but builds on other, current and past, sources of popularised discourse. Thus, the TikTok trend discussed in this paper did not just appear out of thin air but needs to be regarded within the context of previous history in (online) dating trends.

“He’s a 10 but” actively refers to and constructs the identity of a person, both the conceptualised and idealised “10” but also of the real people involved in the interview. The term “identity” here describes a broad range of features and their relevance to the trend and the dating culture connected to it (Johnstone, 2018b). Identity does not simply exist but is a fluid concept that reflects on social norms in a specific context and is constantly reshaped through them (Blommaert, 2005). In this dating-related context, it may point to a relationship status, sexual orientation or, as the trend suggests, how a person needs to act in order to be most desirable. To determine this character, the TikTok trend indexes specific signs that become detrimental to understanding the stereotypes that are being reinforced. This further promotes ascribing identities to others as a community and requires a common repertoire of understanding the same semiotic features. Looking at the constructed identities gives insight into the prejudices applied to the “10” in the TikTok trend and the significant signs needed to have a common consensus on those identities.

Curating identities online goes hand in hand with conceptualising a new truth in dating culture. The “He’s a 10 but…” trend on TikTok reinforces a specific dating narrative that is supported by virality and the repetition of the trend all over the platform. Internet discourse has offset a de-rationalisation of truth (Swanenberg, 2022b) through its ability to fragment the public sphere. This means that different niches online now have wildly different conceptions of knowledge. Away from a worldview imposed by moral and legislative authorities such as the state or religion, this leads to individualisation of truth tied to identity (Swanenberg, 2022b). Highly emotionalised, “truth” becomes tied to one’s identity and determines group belonging. The trend format creates such a vacuum of knowledge, actively shaping lived realities of modern dating culture.

“He’s a 10 but he only wears Flip Flops”

Eugene Litman’s TikTok is a 12-second clip of him presenting three statements to a young woman in a street interview style. Uploaded on 9th October 2022, it is a somewhat recent video with significant uptake. While at 3.1 million views, it has over 145 thousand likes and a little over 1700 comments. The caption attached to the video reads “Wait until the end 😳 #interview #publicinterview”. In the video itself, Litman is shown with a phone in hand recording himself and his interviewee. It is a fast back and forth, the camera focussing on Litman speaking and then zooming into the young woman giving her response. This builds anticipation, suspense quickly broken off by the short numbers from the interviewee. For the viewer this is easily digestible content that does not take much time to comprehend, yet also restricts critical thinking.

Screenshot of Eugene Litman TikTok

This video is a typical example of the trend. With its flashy titles and weird question props, it grabs the viewers’ attention and offers entertainment value (zoeunlimited, 2022). Not only is this the recipe for success for most TikTok formats, but their repetition by specific creators also further shapes the narratives within the trend. In Litman’s case and many others, it is important to note that he only asks a small demographic of middle-class women in their 20s these questions. Additionally, while the “but”-statements, the character's quirks, are all proposed by the interviewer, the women are always the ones involved in judging the perceived “10”. The image created is therefore limited to a very specific frame. Depending on the audience’s uptake, this directly shapes not only the identity prescribed to the imagined 10/10 partner but just as well that of the women in the interview.

The Rating Game

TikTok trends like this one are not entirely new but derive from previous trends and established dating discourse in mainstream pop culture. In the 2000s, scale-based rating games had already been spread through magazines such as CBS news (2009), publishing an article on “The Rating Game” (Toney, 2009), a book made to find the most suitable partner by assigning numbers to their best and worst qualities. With their emergence into pop culture, the initial spread of this categorisation in dating has shaped discourse ever since. Normalising ascribing numbers to people and calculating compatibility based on these scores preceded the gamification of this format through TikTok. While never directly referring to this specific literature of the 2000s, the content exemplifies a popular narrative that has been subjected to the concept of intertextuality. Applying these to the new trend builds on the previous “rating game” and expands it to a broader audience with added messages (Johnstone, 2018). The formatting based on the TikTok affordances also plays into this dating discourse. Being a short, snappy and easily consumable interview, it draws the viewer in and incentivises them to “rate along”. Through this gamification, the viral uptake of the format has progressively influenced discourse on dating. The updated affordances of the internet have made it possible to directly interact with content and push it algorithmically through hashtags such as #publicinterview. This causes less reflected and more judgemental comments to receive significant attention.

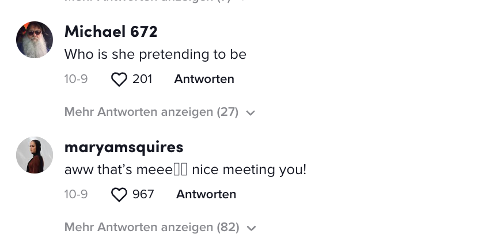

Comments under Eugene Litman's video

On Litman’s TikTok this can be observed in the comment section of his videos. While many praise the woman in the video for her looks, asking for her account name to follow her, an equal amount of commenters take issue with her performed identity. Since identities are not a stable category, the woman in the video actively constructs her own but also the "imagined 10" through her performance (Swanenberg, 2022a). Relying on semiotic features, others can then ascribe an identity (Swanenberg, 2022a). Wanting to socially categorise identity, these signs must be understood by the viewers to decide whether they agree or do not agree with her (Johnstone, 2018). According to Tarrant (2009), men wearing sandals may fall victim to the Californian frat-boy stereotype. Recognising this implicit meaning reveals that the two people in the TikTok interview are familiar with the same language repertoire. The young woman is therefore able to connect a vivid identity to the phrase, making it possible to give it a “-4” rating. Understanding this interaction as one with indexical importance points towards the reinforcement of a specific type of dating culture. Ascribing these features to a potential partner generalises identity, further contributing to the trend's success in building a dating narrative based on superficial stereotypes. While “wearing flip-flops” in many contexts does not reveal much about a person’s characteristics, they become a crucial factor in the “He is a 10 but” format. As the trend promotes discourse over a fictive version of a potential partner, the disconnect to that ideal results in the wide acceptance of categorisations (Blommaert, 2005).

Shaping a new truth in dating

Not only the TikTok interview format but the way the discourse of the trend is communicated has an active influence on how its content is being received. The discourse that results from this formatting directly influences what is perceived as “the right way” of viewing dating, actively constructing a widely accepted “truth” (Johnstone, 2018c). New discursive practices on the internet have reshaped common views on what is considered “knowledge”. As a “de-rationalised” notion, the democratisation of authority online has removed the importance away from religion and legislation and replaced it with the more emotionally charged notion of moralisation (Swanenberg, 2022b). Instead of being tied to one institutionalised source, this has fragmented and individualised knowledge to various niches that can potentially stand in conflict with each other. In dating discourse online this has a direct influence on its dominating narratives. A trend such as TikTok’s ‘He’s a 10 but…” formats knowledge, producing a discourse of truth through specific repertoire (Swanenberg, 2022b). In the example “he only wears flipflops”, the irrational nature of the statement is quickly replaced by prior pop-culture references to the earlier frat-boy stereotype (Tarrant, 2009) and the negative associations it brings with it. Through the repetition of this established and moralised idea, a “bandwagon” is created, attributing truth to it due to its popularity (Swanenberg, 2022b).

The online platform and the way the users create content on it also highly contribute to this perception. Framing women as the instigators of superficial dating discourse, Eugene Litman’s video exemplifies this through stylistic choices such as his very narrow choice of interview participants. For this trend, he interviews middle-class women in their 20s in public settings, making his videos feel spontaneous and appealing to a similar audience, limiting the communicative scope to a homogenous crowd. The use of zooms on the woman speaking put further emphasis on her statements, bringing her into the focus of the video. Labelled as a “must watch”, the video is also framed to be of importance. While these platform affordances both shape and limit the way this truth is produced, discourse and knowledge are never immediately transferred from person to person but are mediated through various communicative modes (Johnstone, 2018c). Besides speech and gestures, the zooming and the excessive focus on the woman being interviewed, the TikTok also uses onscreen text in different colours to differentiate each speaker, making the video become even more accessible. Instead of having to sit down at home and watch the video with the volume up, it can now be watched “on the go” in public, without disturbing others. With little content to digest comes little critical questioning of the frames being applied. While giving short answers to the interviewer, the emphasis on her statements shape her to be the instigator of this superficial discourse, making her susceptible to both very negative and positive audience perception.

Conclusion

Since the success of Eugene Litman’s TikTok, the woman in the interview has started posting her own videos to the platform, capitalising on the attention and demand of the commenters in her support. In one of her videos, she picks up on another dating-related trend, reinforcing the same discourse and validating the identity ascribed to her. With viral uptake and their playful style, these TikTok trends have normalised superficial dating narratives with little to no critique, normalising constant judgement and categorisation of both of the participants involved and the imagined “10”. As truth has lost its definite identity and has become a puzzle made of different discourses (Swanenberg, 2022b), the most dominant dating discourse becomes the most widely accepted. Easily consumable trends such as “He’s a 10 but…” contribute to building dating discourse around an unachievable ideal and actively invite the audience to judge the statements made by the women involved in these interviews.

References:

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A Critical Introduction. Chapter 8: Identity. Cambridge University Press.

CBS News. (2009, June 24). How To Play The “Rating Game” When Dating. Retrieved October 10, 2022

Johnstone, B. (2018). Discourse Analysis (Introducing Linguistics). 6 Prior Texts, Prior Discourses (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Johnstone, B. (2018b). Discourse Analysis (Introducing Linguistics). 5 Participants in Discourse: Relationships, Roles, Identities (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Johnstone, B. (2018c). Discourse Analysis (Introducing Linguistics). In 7 Discourse and Medium (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Litman, E. Wait until the end 😳 #interview #publicinterview. (2022, October 8). [Video]. TikTok.

maryamsquires. (2022, December). [Video]. TikTok. Retrieved December 14, 2022

Swanenberg, J. (2022a). 08 Discourse Analysis 2022 Identity [PowerPoint slides].

Swanenberg, J. (2022b). 09 Discourse analysis 2022 [PowerPoint slides].

Tarrant, S. (2009,). Men and Feminism: Seal Studies. Seal Press (CA).

Toney, R. (2009,). The Rating Game: The Foolproof Formula for Finding Your Perfect Soul Mate. St. Martin's Publishing Group

zoeunlimited. (2022, October 27). she’s a 10 but she has a lot of guy friends [Video]. YouTube.