Our Parasocial Relationship with Dan and Phil

For well over a decade Dan Howell and Phil Lester, mostly known as Dan and Phil, have entertained Gen Z through their quirky and relatable YouTube videos. The British creators started making content when the platform emerged, growing with it an audience of millions of young viewers. Through a variety of ever-changing formats, they exposed all their favorite interests, hobbies, and personal stories from their late teens up to their early thirties. While either has their personal channels, Dan being seen as the edgier, emotional counterpart to a light-hearted, happy Phil, their constant collaborations fostered a fandom that grew incredibly attached to the duo.

Blurring the lines between distant entertainers and close companions to their fans, a long-lasting relationship has formed between them. This parasocial construct has led to a community of dedicated fans forming over their love for the creators. Through fan pages, Twitter threads, and Tumblr blogs, these fans have built their own Dan and Phil universe, anticipating each video upload and picking each little detail apart. One of the most burning questions by fans has always been the potential romantic relationship shared by the creators, ultimately forcing each of them to come out as gay online. This built-up pressure supported by the parasocial nature of these YouTube channels demands exploration of the unhealthy and obsessive behaviors they have raised Gen Z to engage in.

Parasocial relationships and mass media

Even though the internet has strongly promoted engaging in parasocial relationships, their existence is not entirely new. Horton and Wohl (1956) describe the phenomenon as a one-sided and non-dialectical exchange, being able to engage with the performer but not the same way around. Usually, the performer is behind a microphone or in front of a camera, giving them the power to control most of the input into the relationship that is then spread to the public. By creating a specific “persona” (Horton & Wohl, 1956, p. 216) they appeal to an audience of like-minded people. Finding relatability in what is presented to them, the audience idealizes this character to an extent that may even exceed what can possibly be achieved in real-life, strengthening the bond they feel towards them. On the other hand, the performer plays into this imaginative relationship through various modes of intimacy, such as directly addressing the audience member, whispering as if close to them, or answering fan mail. To this extent parasocial relationships have come to be a normal, yet partially fictitious part of our daily lives that reaches back beyond mass media with book character obsessions (Hitchcock, 2021). When turned unhealthy, however, the parasocial has a history of harmful behaviors, including stalking and harassment in demand of real reciprocation to the unfulfilled bond (Horton & Wohl, 1956). The input needed for a working parasocial practice, while maintaining an authentic enough image, becomes a balancing act that has become progressively harder with new technological affordances and formats on the internet.

The Dan and Phil ”Phandom”

The community built around Dan and Phil’s content grew just as fast as the creators' popularity on the YouTube platform. With a collective of over 10 million subscribers on their main channels from all over the world, many viewers sharing their parasocial friendship with the creators came together to create the “phandom”. As a “ship name” of Dan and Phil (Phan) the term sparked early conspiracies about their supposed romantic relationship, connecting their fans to a collective, yet fictitious, idea of the duo. Dating back to forum entries around 2012 (Urban Dictionary, 2012), these ideas have fuelled the viewership ever since. As a group filled with socially awkward teenagers, Allie Tricaso (2022), a former fan, describes the “phandom” as a homogeneous construct with similar interests in anime and pop culture and an emo phase. Feeling like social outcasts in their real-life circles, the Dan and Phil YouTube videos offered escape and reassurance, with videos reflecting these same emotional struggles.

The pitfalls of intimacy

With an audience so tied to both YouTube friends and their community, many different actors have tried to exploit this parasocial relationship for their gain. Other creators on the platform like Shane Dawson have heavily pushed the relationship rumors, as far as inviting “the psychic twins” onto a now-deleted podcast episode (felluca, 2017) to spread further conspiracies. In publishing these stories, influencers not only drive traffic to their content but reassure the audience that they have a valid reason to believe in the potential relationship between Dan and Phil. Similar to the way one would believe “a friend of a friend” in a high school classroom, this parasocial network not only spreads but engrains theories through this repeated process. While claiming not to try to 'out' anyone (felluca, 2017), an influencer with millions of followers engaging in the rumors so openly justifies fans to do the same.

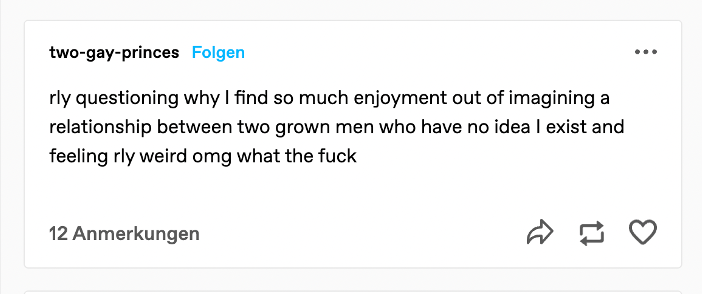

Tumblr comment from 2015 (user information redacted)

A second actor in normalizing the suggestion of a romantic relationship between the two creators is the community itself. Oriented around the personality of their favorite YouTubers, they spark not only a space to connect but new emerging fan content and discussions (Mackie, 2021). Seemingly critical, fans occasionally reveal doubt about their obsession with Dan and Phil, yet the postings in support of rumors tend to drown out these voices. Deceivingly, these online communities do not reflect what is thought to be an equal community of supporters but reveal “parasocial relations within parasocial relations” (Mackie, 2021). As not everyone consuming Dan and Phil’s content actively contributes to the “phandom”, the overarching consensus on topics such as their relationship becomes hierarchical. Posts with the most engagement become the voice of the community. Combined with the thrill of spectacle, this has further normalized the romantic suggestion of the two creators.

The theories surrounding Dan and Phil’s sexuality emerged at a time they were not ready to address these rumors for themselves. With questions asking to come out appearing early on, Dan in particular felt the pressure of his viewers years before he was even able to address them with his closest family. He posted his video “Basically, I’m Gay” (Howell, 2019) a decade after these first comments emerged, showing the intensity of this parasocial construct in connection to his private life and off-screen identity.

Fostering a parasocial environment

While the nature of the parasocial suggests no room for mutual friendship (Horton & Wohl, 1956, p. 218), the environment these relationships are built contributes immensely to its success with an audience. The “personality” shows of the 1950s (Horton & Wohl, 1956, p. 217) developed in combination with more private consumption due to the unpredictability of post-war America and led to a similar “crisis of belonging” in recent years (Mackie, 2021). These shows would be hosted in intimate settings and address their audience directly (Mackie, 2021). Nowadays, with an abundance of economic resources but a decline in social institutions to upkeep real-life community building in the western world, many have turned to the parasocial instead. Having fewer opportunities to connect locally, the internet offers endless content and decentralized niches, making it easy to combat this lack of cultural and social bonding activities. Further, online content can be highly stylized to appeal to the desires of an audience, wanting them to return to it to escape their uncomfortable realities (Hitchcock, 2021). As awkward teenagers, feeling little or no belonging in their everyday school environments, the stories Dan and Phil tell from their bedrooms seem oddly familiar as they share embarrassing tales and demonstrate their successful lives as social outcasts. This vulnerability is welcomed by the audience yet does not need to be reciprocated (Hitchcock, 2021). While the creators share intimate details of their lives on public display, trust is built with the viewers. By showing both aspirational aspects of online fame such as conventions and travel opportunities such as their trip to Japan in 2015, Dan and Phil also reflect the mundanity of life by playing games or baking for Christmas. As an effect, the viewer feels included in this parasocial friendship, being able to experience both big and small milestones in the Youtubers’ lives, which further supports its escapist tendencies (Hitchcock, 2021).

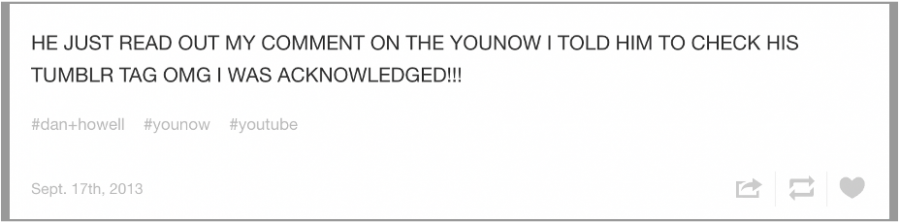

Tumblr comment from 2013

Beyond the fan mail and radio phone calls of the 1950s, the internet offers a plethora of modes of interaction regarding the “phandom”. Question and answer formats, YouTube comment replies, and live streams on platforms such as YouNow have actively shaped the transactional potential of our current parasocial relationships. In the case of Dan and Phil, big tours such as “Interactive Introverts” and formats such as “Viewers pick Dan’s outfit” create virtual and real-life spaces to engage directly with fans, upkeeping the parasocial relationship through this acknowledgment. Through sincere-seeming shoutouts a video creator can make their audience feel more connected to them and thus invest in the “friendship” by engaging with more content, creating revenue for the media personality (Howell, 2022). This, however, is not limited solely to money-making purposes by the creator, but the development of parasocial escapism into “consuming intimacy as a product” (Hitchcock, 2021). Choosing not to directly engage with the creators as a viewer does not limit the vulnerability expressed by the online performers. Being able to remain in anonymous isolation, an audience also has the opportunity to circumvent the social discomfort of potentially humiliating experiences by consuming these parasocial relationships (Hitchcock, 2021). Through their large variety of video formats and content, Dan and Phil have actively fed into many of these parasocial aspects. Offering friendship behind a screen targets the progressing need for sociocultural bonding, yet also faces a dilemma. As the suggested intimacy of the relationship can never be entirely reciprocated, the more intense it gets, the more severe this unfulfillment becomes (Mackie, 2021).

Our friend Dan Howell

Social media platforms as a constantly available feature of the internet have increased a fandom’s access to their creator. Being able to engage in parasocial relationships anywhere at any time has heightened their intensity. Connecting over long-term inside jokes and picking up on recent trends and news makes it possible for creators and audiences alike to conform to this language of friendship (Mackie, 2021) to a new degree. In a video from November 2022, Dan is quoted saying “you can only know what they show you, but sometimes they show you more than they show people in the real world” due to the real-life social disconnect and the fan community build around him. Having both parties, the creator and the audience, directly involved with each other bears dangers as much as it provides comfort. “At its worst, a parasocial relationship can lead to stalking which might make someone rent a secret apartment for filming” (Howell, 2022), is one of the consequences Dan describes when talking about his openness with his audience. Feeling entitled to real-life reciprocation of such an intimate parasocial relationship may lead to obsessive behavior. As an audience made of mainly young and impressionable viewers raised by the internet, its parasocial relationships have proven unhealthy with its yearlong normalization of suggesting a romantic relationship and boundary crossing. In his video, Dan describes balancing this “parasocial diet”, fostering healthy connections between creators and audiences. Having contributed to rumors with clickbait titles such as “We are in a relationship”, he has capitalized off the obsessive tendencies of his most prominent viewers but also sees the risks that have brought with it saying, “just try not to get angry if some prophesized fan fiction doesn’t come to life or get crushingly disappointed if you ever meet me” (Howell, 2022).

An online connection

No matter if intended or not, we form and engage in parasocial relationships at all times. From our favorite news presenter to YouTubers like Dan and Phil, mass media formats have incentivized us to invest in these bonds to escape the uncomfortableness of everyday life and find belonging in these familiar figures. Horton and Wohl (1956) describe parasocial relationships as “observing intimacy at a distance” and as much as we are still removed from the creators we admire, the added modes of communication and interaction on the internet have further blurred the boundaries between the more anonymous viewers and the friends they make on social media. Addressing them as Dan and Phil instead of Howell and Lester throughout this paper certainly also shows my lack of immunity to the impact this parasocial relationship has had on my generation. The intense bond of the “phandom” shows the consequences of these social media advancements on a young audience and serves as a reminder to stay critical when engaging online.

References

Hitchcock, C. (2021, September 9). Take Me Away. Real Life Magazine.

Horton, D. & Wohl, R. (1956, August). Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229.

Howell, D. (2019, June 13). Basically, I’m Gay [Video]. YouTube.

Howell, D. (2022, November 22). We Are In A Relationship [Video]. YouTube.

Mackie, B. (2021, July 1). Why Can’t We Be Friends? Real Life Magazine.

Tumblr post. (2015, March 11). Tumblr.