Good Job, +15 Points: How the internet makes sense of China’s Social Credit Score system

From an Orwellian-like surveillance system to every comedian’s throwaway joke, how China’s Social Credit Score System (SoCS) policy is condensed into a popular internet meme is interesting. Even if you have not heard about the actual policy, you have probably seen netizens with their ‘scores’ deducted, as they share their hot takes on China and Taiwan. Becoming more and more tongue-in-cheek in dialogues, it is certainly “a shared social phenomenon” (Shifman, 2013, p.365). In fact, Shifman’s framework can approach them scientifically, specifically dissecting them by content (the ideas and ideologies conveyed), forms (the appearances where these ideas are presented and then perceived) and stance (how users can position themselves and participate in them) (p.367).

As the article aims to analyze the derivative memes, it will be investigated how the SoCS memes can construct a poor 'aesthetic' impression on top of a joke 'judgement' to the speaker, as well as underlining a society of surveillance as personae and actions are introduced in the form of video, games, and more.

What Make Them Tick(le)

Originally intended for Chinese viewers, viral Mandarin social media videos, such as actor John Cena's Mandarin apology video and other eye-catching Chinese TikToks are among the common remix subjects. With both their faces and Mandarin being misunderstood and reinterpreted in another context, this forms another type of aesthetics. To Goriunova (2014), memes’ aesthetics stems from a “multi-layered individuation” (p.62), like a theatre unfolding lasting ideas. As “loaded forms” (p.65) under specific cultural and historical contexts, they reflect collective concerns about the status quo, plus its effect on the author with “conceptual personae” (p.66) at play. The exoticism of a foreign language and race may also contribute to the memes' rise.

Furthermore, China’s sensitiveness in simply mentioning Taiwan or the June 4th Incident is often mocked. China's exaggerated responses in these memes are seriously refuted by Zhou, who questions their accuracy in comparing with the official purposes of SoCS. In her opinion, mockery can be connected to techno-Orientalism which refers to presenting the East, especially China, as a threat, being able to colonize the West with their advanced technology (Roh et al, 2015, pp.11-12). Her analysis was panned on Twitter, as commentators prioritized the memes’ ‘silliness’ over accuracy.

With Berger’s emphasis on word of mouth in viewers’ affection (2014), I would argue that they build up a political collectivity aside from the laughs. As their emotions are aroused, people garner more sharing to communicate their desired identities (p.591), then infer a more engaging experience, cope with and make sense of challenging situations, or be part of a group. As one of the main arenas for the meme, this article will also shed light on the repeated political arguments in the memes on Reddit, where its sub-reddit mechanism flourishes among groups which specialize in creating memes and further remixes.

Particularly, the article intends to sample posts from r/socialcreditmemes, a 2,000-member subreddit consisting of SoCS memes and creative spin-offs like a text-based game. Aside from this, representative posts are also selected from the query “social credit memes” and its major variant “John Xina” on r/memes, Reddit’s largest meme sub-reddit with nearly 25 million members, to see how they are perceived in a more mainstream community.

China's Social Credit Score as context

China’s SoCS scheme debuted in 2014 as an expansion of the existing system for business and was trialled in cities like Suzhou (Bloomberg News, 2019). There, citizens are ranked with a base score and are encouraged to work it up by making ‘right’ choices in daily lives or by doing good deeds. Reversely, not only will they lose their ability to fly and more if the rankings drop to unacceptable levels, but their names and mugshots will also be displayed for public shaming. These, plus restricting local petitions to higher authorities (shangfang) by automatically reducing their ranks, attracted criticism from the West for intruding into individual privacy and freedom.

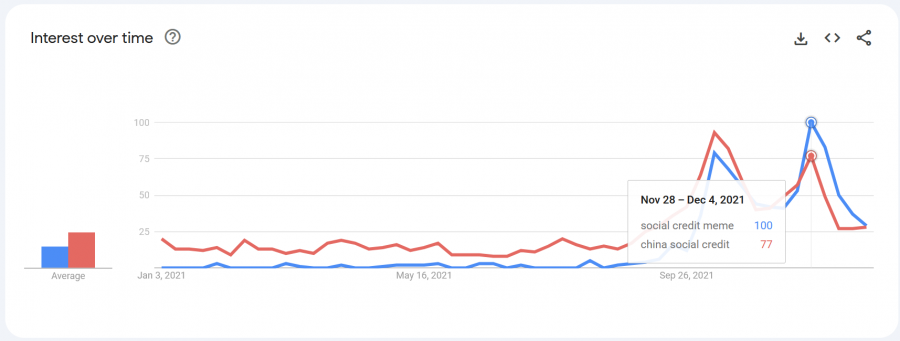

Despite its name, the SoCS memes did not come from the Chinese social credit scores. Instead, its origins are more akin to wumao (50 cents) in the Chinese internet landscape: commentators routinely posting pro-China troll comments for minimal monetary returns. Interestingly, it also links to the Russian context, where the meme started as a mockery of pro-China comments written in broken Russian on local forums. Their salaries for their ‘hard work’ – 15 rubles per comment – are then highlighted in images circulating in 2021, which are sarcastically related to social credits rather than money. In the West, meanwhile, although it was used on Reddit earliest in April of that year, it wasn’t until late 2021 when various video remixes went viral on YouTube, which in turn pushed the query “social credit meme” to its highest per Google Trends.

Figure 1: An infographic showing the search interests for query “social credit meme” reaching its peak in late 2021, with a slightly declined one for “china social credit” for comparison. Data source: Google Trends.

Routing Out the Meme

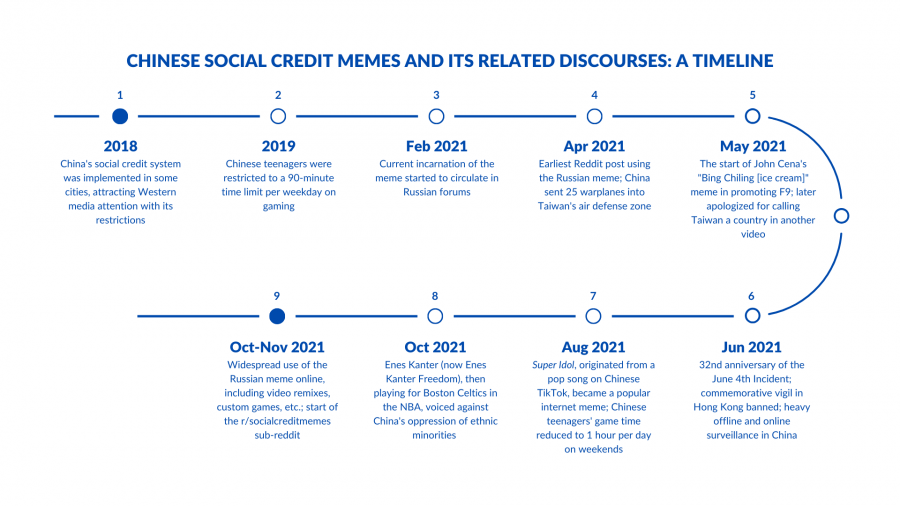

According to Shifman (2013), the spread of memes "is a process of express diffusion, reproduced in various imitation means, and the adaptations they made in sustaining in the sociocultural environment" (p.365). In order to trace back the spread of the SoCS memes, as well their variants and imitations, I utilized the “ability to trace the spread and evolution of memes” (ibid) mentioned in the Shifman article and came up with the following graph. The events listed here can be categorized into three larger themes, such as the original memes’ context, the concurrent ‘Chinese’ memes, and Chinese current affairs, whose significance in evolving the meme would be discussed in detail later.

Figure 2: A timeline showing events and internet phenomena that led to the rise of SoCS memes.

The Original Social Credit Score Memes

To begin with, it is necessary to look at the initial reaction images.

Figure 3: The original +15 social credits meme.

In terms of the content, the images mainly consist of other internet users judging the original poster’s speech under the fictional ‘social credits’. Having a direct opposite, it (dis)encourages one kind of behaviour over the other – not recognizing Taiwan as a country or the June 4th Incident in the case of most SoCS memes. Meanwhile, in terms of stance, they suggest an overarching ‘system’ which together with the poster were constantly tracked . These images, therefore, are akin to fine tickets issued to drivers, satirically keeping users at bay in expressing their opinions to prevent a 'fatal' score deduction.

These images, therefore, are akin to fine tickets issued to drivers, satirically keeping users at bay in expressing their opinions to prevent a 'fatal' score deduction.

With the editability of the images, however, users can also ‘watch’ others’ activities and hand these ‘tickets’ out as they (do not) like.

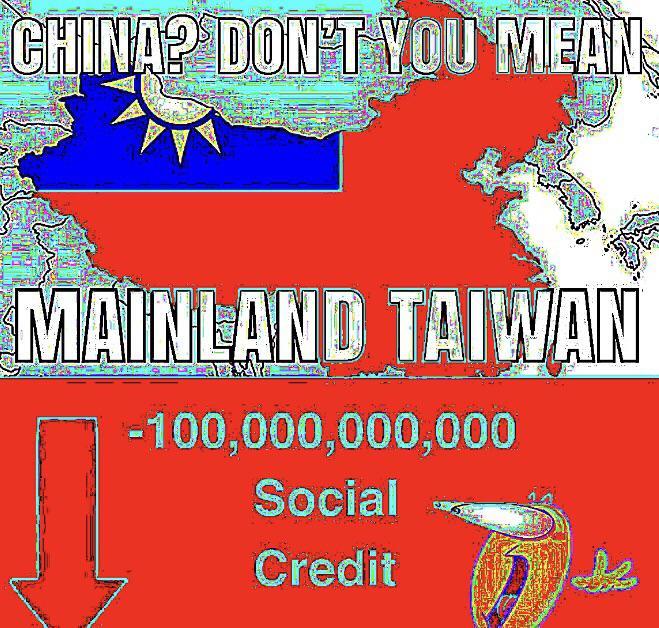

Figure 4a: A similarly-formatted SoCS meme, but themed under Chiang Kai-shek era Taiwan instead.

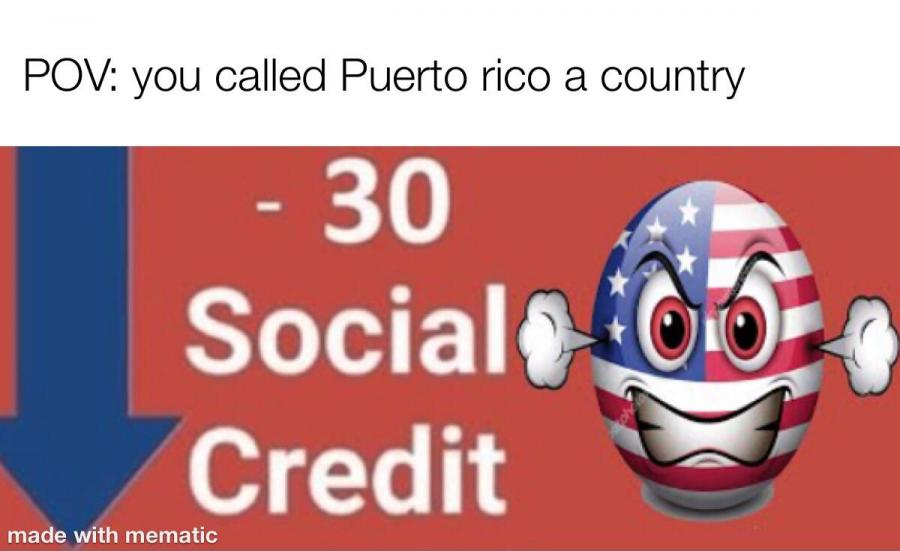

Figure 4b: A similarly-formatted SoCS meme, America-themed.

Much like Shifman’s analysis of the “Leave Briney Alone” meme (2013, p.370), the low-effort form is imitated on top of the original image, now with more apparent links to a country’s culture and history. Here, their composition remains the same, with the +/- [number] social credit and huge symbolizing arrows continuing to be seen. The surveilling ‘credit’ system also stayed, but its ‘leader’ can be the head of a specific state, like seeing Chiang Kai-shek’s face in the Taiwanese variant. Being more nationally specific, nationalism can also be satirized. From the humanified ‘America’ emoji’s angry face, it can be implied that ‘it’ sees the speaker as ‘not American’, as they see Puerto Rico, geographically part of the US but less so identity-wise, as a country.

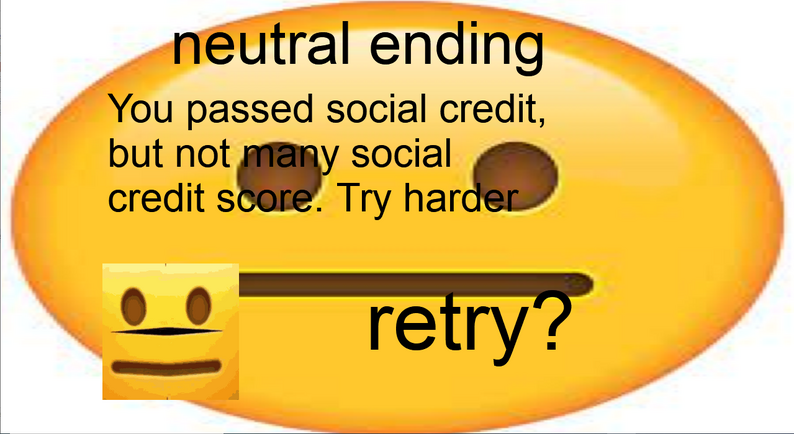

Figure 5: A demo ending screen from a computer game based on the SoCS meme.

In contrast to the surveillance system referenced, the low quality of the memes dents the possible techno-Orientalist vision, which resents authoritarian China and reflects the fear of being closely monitored (Zhou, 2021). In the variations, only the latter meaning persists while the “referential” function (Shifman, 2013, p.367) – their underlying contexts – is easily changeable. Meanwhile, although Asian stereotypes can make technological advancements to be more ‘mythical’ (Roh et al, 2015, pp.14-15), the mishmash of arrows, Chinese and English characters around the ancient Chinese man emoji show the little effort paid in making the meme – a style then imitated in derivative custom games. Presented in badly-recreated images, the SoCS system is less sophisticated and hastily done, but still eerie in principle.

Presented in badly-recreated images, the SoCS system is less sophisticated and hastily done, but still eerie in principle.

Lost in Translation

Moreover, SoCS meme remixes can be a “social response” (Goriunova, 2014, p.58), through changing perceptions of celebrities like John Cena. Claiming Taiwan “the first country” to watch F9, the Chinese social media outrage forced him to apologize to secure the Chinese box office. Blasted in the West, the image of John Xina – combining Cena with Xi Jinping – was created (Carry, 2021). The political critiques are then slightly hampered in being remixed with the Bing Chiling [ice cream in Hanyu Pinyin] meme, another joke based on his Mandarin and exaggerated motions in promoting the film on Chinese Twitter counterpart, Weibo.

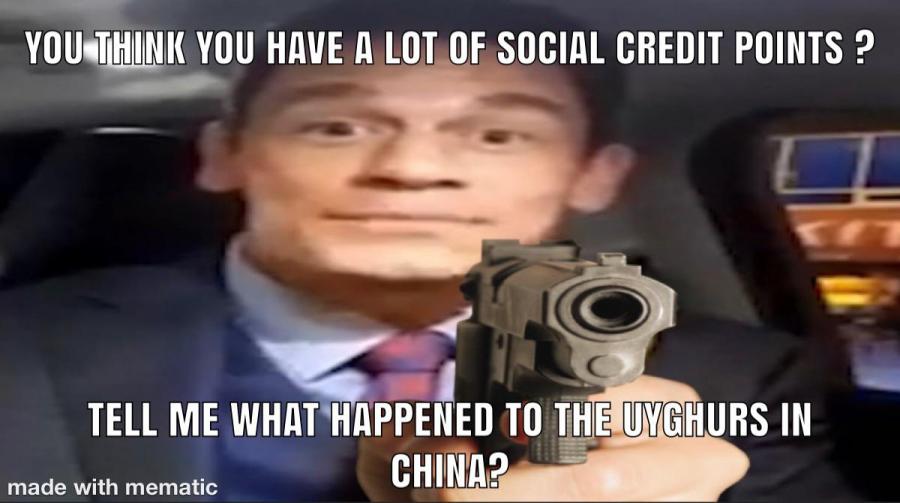

Figure 6: A composited photo of John Cena (from his bing chilling [ice cream] F9 promo video) with a gun, daring the user to risk losing their social credits and speak about the Uyghurs.

Using Cena's light-hearted internet image as the medium, the memes “work from within” (Goriunova, 2014, p.66), building an ‘enforcer’ or ‘loyalist’ image to both the SoCS meme system and Cena, who had been a popular figure on the internet for years. They are also externally intertwined with “larger assemblages of power, normativity, and history” (ibid, p.65). Here, not only are China-Taiwan relations parodied as a recurring topic, but Hollywood’s reliance on the Chinese market is also highlighted, as the original videos are made to promote the blockbuster in the nation, spoken with local audiences in mind. The Xena meme can hence be a collective resonation against such inclination, in making fun of the language used and the faces who are willing to do so.

On the other hand, Chinese viral videos are also the source for SoCS meme remixes, as a part of being subjected to both Chinese- and English-speaking online communities. A more well-known example is Super Idol, stemming from a Putonghua pop song 热爱105°C的你 [Loving you at 105°C] on Chinese TikTok. Debuted in 2019, it was not known before being reuploaded to YouTube 2 years later. Intended to sell bottled water to a Chinese audience (the 105°C in the title stands for the temperature used in distilling water), its lyrics were “incompatible” (Goriunova, 2014, p.59) to most of the internet. However, the accompanying actions from the actor in the video, often characterized as an 'oily' way of flirting on the Chinese internet, opened a space between itself and part of existing meme formats (p.60). As it crossed over with SoCS memes, the intended heartwarming and positive message from the motions is appropriated like a means of aggression, "playing the network" (p.66) of SoCS memes as a violator to the existing ‘system’.

Figure 7: A capture of the singer of Loving you at 105°C, superimposed in front of Tiananmen Square, overlaid with benign terms breaching the ‘rules’ in SoCS memes. His social credit score was, of course, deducted to the point of ‘execution’ at the end.

Though misinterpreting Putonghua in achieving the comedic effect in the memes, the Chinese online figures are at play with a larger network of meanings, instead of being excluded from it. Both the Super Idol and Cena’s Bing Chiling memes originated from Douyin, which is simultaneously rising with TikTok globally. With a lot of the content from the China-only Douyin being cross-posted to TikTok, Western users enjoy a large influx of content broadcast in a different language. As the eye-catching performances in these short videos are becoming “well-established discursive formations” (Goriunova, 2014, p.65) upon daily usage of the platform, they utilise the act and project fictional alter egos onto them, per their understanding of the Chinese society. Hence, we see Super Idol offending the SoCS instead of singing a love song, while Cena is dressed up in a Maoist outfit.

The (n)everchanging politics

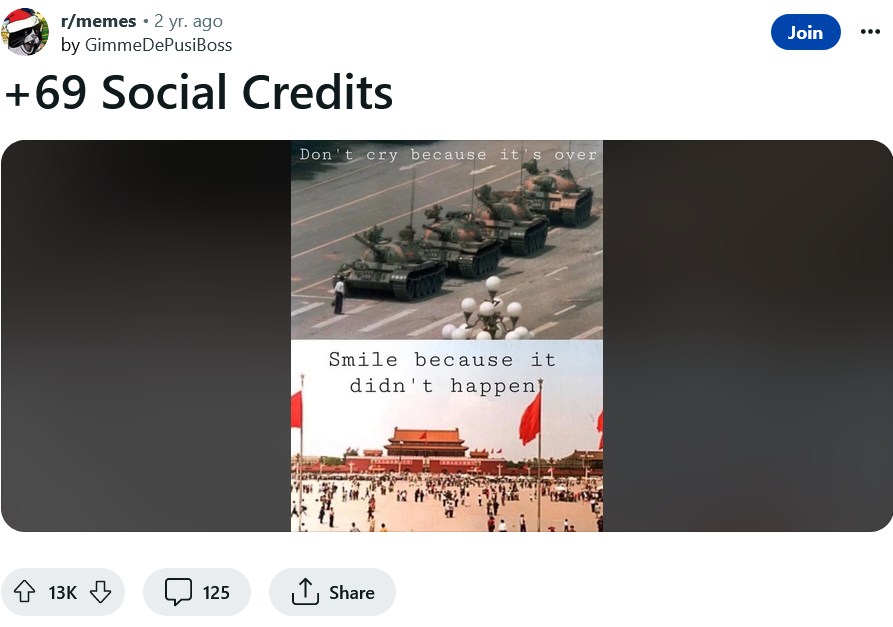

Figure 8a: A meme stressing the June 4th Incident didn’t happen, which gets a rise in SoCS.

Figure 8b: A meme recognizing China as ‘West Taiwan’, which get a drop in SoCS.

A recurring theme in SoCS memes is satirizing of Chinese political censors, by mimicking deniers of Taiwan and the June 4th Incident. Like variants that play on national stereotypes, these convey a sense of belonging closer to official Chinese narratives. Adding their own twists in ‘confirming’ their ‘non-existence’, netizens respond to show that they are “in-the-know” (Berger, 2014, p.590) of the SoCS mechanism, enhancing their sense of belonging (and their fictional ‘scores’) in playing the common denial as the others. Yet, continuing such ‘theory’ can be confusing to some out of the loop, as seen in one that mistakes the actual movement and the censorship with movies in the 1989 meme, contrary to the “useful information” motive Berger suggested (Berger, 2014, p.590).

Compared to continuing discourses like Taiwan, individual events are less likely to be reproduced in SoCS memes, unless overlapped with other fandoms like sports and gaming. The former is best exemplified by then-Boston Celtics player Enes Kanter, a vocal critic against Chinese government’s oppression of Tibetans in October 2021.

Figure 9: A meme showing Xi Jinping’s displeasure in seeing Kanter’s custom shoes with June 4th imagery and called up John Cena as his hitman.

As a hugely popular platform for discussing the NBA games, Kanter’s activism was shared and appreciated by Reddit users and then remixed with preceding John Xina and SoCS memes. This can be seen as grasping of people’s “common ground” (Berger, 2014, p.595) on both the tournament and Kanter’s action, as well as raising an amused feeling with the exaggerated Cena posing in contrast to Kanter’s smugness.

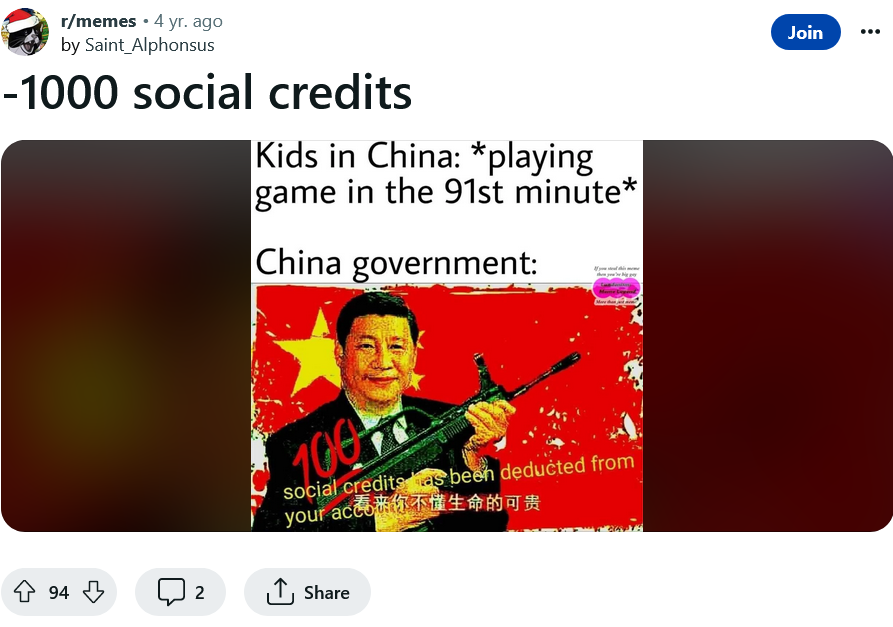

Figure 9a: A 2019 SoCS meme on China’s teenage gaming time limits.

Figure 9b: An SoCS meme on China’s teenage gaming time limits in 2021, citing a GIF of SWAT-like figures breaking into to a streamer’s house with explosions.

Meanwhile, the latter shows how an issue is more visible as the memes become more popular. To curb the online addiction among teenagers, the government restricted their time playing online games to 90 minutes per weekday in 2019. As China’s SoCS had been running by then, there are memes linking the two. Despite posting on a large sub-reddit and a crucial platform for gamers, it’s less resonated than in 2021, stemming from the reduced time limit to 1 hour per day on weekends. In addition to the sensationalist motion and the generic format used, the SoCS meme achieved Berger’s venting and sense-making effects as well (Berger, 2014, p.592). With the ‘score’ a physical ‘consequence’ at any time, this may help vent Western gamers’ potential sense of alienation to the policy and make sense of it – albeit in a less accurate and more eye-catching way.

With the ‘score’ a physical ‘consequence’ at any time, this may help vent Western gamers’ potential sense of alienation to the policy and make sense of it – albeit in a less accurate and more eye-catching way.

Closing Out

The effects of the SoCS memes are a two-fold issue in building a community. On the one hand, they are a means for the West to make sense of the Chinese society, whose concept of a continuous surveillance system on citizens sounds alien to those under a more individualistic and private setting. With the overarching system compressed in replicable images, their underlying fear is summarized, while also being the 'in-the-know' device in finding those who have a similar emotion. This eventually fulfils the identity-signalling function of sharing in Berger (2014, pp.589-90), conveying them as those wary and critical of the situation, even when the medium through which this sense is obtained is not always accurate. As a Reddit commentator on Zhou's Vice article wrote: "Sure we might not fully understand, but we get that it's inherently wrong."

However, on the other hand, Chinese netizens – part of the subjects the memes parodied – are less sold on the idea. Although the memes may make discourses, such as government surveillance, easier to be discussed and construct a "common ground" (Berger, 2014, p.591) from people's interests, this viewpoint is limited to looking at China from the outside. Meanwhile, as the insiders, Chinese netizens may be directly subjected to the exact system and may witness more domestic problems than the recurring talking points in these memes. Or, owing to China's complexity and opaqueness in administration, they are more sceptical to the existence of such a system, perceiving the memes as another Western misunderstanding over China. A common outcome from the two types of opposite 'insiders' is a reduced willingness and depth to discuss their Chinese identity with the 'outsiders', because of the lack of a common social tie that encourages them to go deeper (ibid, p.602). This undermines the universality of memes in mass transmission, and hence the lack of further political participation in mass surveillance and other derivative issues.

As it has been established in this article, the SoCS memes mimick the 'unreasonable' parts of national identity and government, through an easily replicable format and style. In the case of China, faces 'for' and 'against' the nation's tight grip are further created out of real-life figures and are then related to other Western aspects of life. Despite creating a unity of rejecting an all-seeing regime within the Western audience, the inherent discrepancies between them and the 'insider' Chinese citizens create a barrier, both in diffusing the meme further across the globe and starting a less-serious conversation over each other's national identities. Even with a universal tool where everyone can chime in, we still do not understand each other – and these memes are proof.

References

Berger, J. (2014). Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(4), 586–607.

Bond, N. (2022, July 4). John Cena’s relationship with Meme Culture, explored. The Ringer.

Boom, D. V. (2021, May 26). John Cena’s China apology: What you need to know. CNET.

Caldwell, D. [Don]. (2018, September 20). China's Social Credit System / +15 Social Credit. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

Carry, O. [Owen]. (2021, October 8). John Xina. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

Cockerell, I. (2022, July 13). Welcome to TikTok’s sanitized version of Xinjiang. Coda Story.

FRANCE 24 English. (2019, May 1). China ranks 'good' and 'bad' citizens with 'social credit' system [Video]. YouTube..

Freedom, E. K. [@EnesFreedom]. (2021, October 25). XI JINPING and the Chinese Communist Party Someone has to teach you a lesson, I will NEVER apologize for speaking [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter.

Gan, N. (2019, February 7). The complex reality of China’s social credit system: hi-tech dystopian plot or low-key incentive scheme? South China Morning Post.

Goriunova, O. (2014). The force of digital aesthetics. on memes, hacking, and individuation. The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, 24(47), 54–75.

Harvey K. (2021, June 19). John Cena Speaking Chinese and Eating Ice Cream / Bing Chilling. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

JustOrdinaryMan. (2021, October 11). Super Idol 的笑容 [The Smile of A Super Idol]. Know Your Meme. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

Kobie, N. (2019, June 7). The complicated truth about China's Social Credit System. WIRED UK. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

kracc bacc. (2021, October 3). how to increase social credit [Video]. YouTube.

Lewis, R. (2017, September 26). Is Puerto Rico Part of the U.S? Here's What to Know. Time.

Rmon_34. (2022, February 16). Such a classic song [Online forum post]. Reddit.

Roh, D. S., Huang, B., & Niu, G. A. (2015). Technologizing orientalism: An introduction. Techno-Orientalism, 1–20.

Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a conceptual troublemaker. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(3), 362–377.

Shirke, R. (2022, January 31). Why is reddit an important source for gamers? Into Indie Games.

Soo, Z. (2023, January 20). China keeping 1 hour daily limit on kids’ online games. AP NEWS.

urfaselol. (2021, October 22). Enes Kanter doubles down on China and calls Xi to close down the Uyghurs Labor Camps [Online forum post]. Reddit.

Wertime, D. (Trans.). (2015, June 17). How to spot a state-funded Chinese internet troll. Foreign Policy.

wafflehusky. (2021, April 5). The user above me gets 15 social credit [Online forum post]. Reddit.

watchfulsquad010. (2021, November 26). Wich movie is that? What do you mean by “it didn’t happen”? [Comment on the online forum post +69 Social Credits]. Reddit.

weebzeewastaken. (2021, October 9). I made this dumb meme into a real game [Online forum post]. Reddit.

Young-Plague. (2021, October 25). Sure we might not fully understand, but we get that it’s inherently wrong [Comment on the online forum post Thank you VICE very cool]. Reddit.

Zhou, V. (2021, October 25). People don’t understand China’s Social Credit, and these memes are proof. VICE.