The Metamorphosis of Patti Smith

Patti Smith has moved from being a celebrity to a public intellectual, but what exactly is the interplay between these two forms and how did she transform?

The Metamorphosis of Patti Smith

Patti Smith is a poetic artist with a dazzling career in music, literature, art, photography and more. She is most famous for her songs and lyrics that have an activist touch like the song ‘People have the Power’, based on the Vietnam War, which could probably be one of the most famous protest songs (Halliday, 2019).

When I first encountered Smith I thought her role did not extend beyond music. That she was a celebrity making activist songs and was famous for being famous (Moran, 2000, 2). But after close-reading her memoir ‘Just Kids’ and studying her life and art, I realized that she owns characteristics of the public intellectual model as well. Her lyrics in ‘People have the Power’, for example, show that she knows how to address the important (historic) events as they unfold in front of her. She understands and captures her Zeitgeist (Heynders, 2016, 2). Her roles, works, and actions as musician, artist, and writer merge into an activist-based practice. Initially, she was a celebrity, but this role is slowly shifting to the role of the public intellectual.

This paper will analyze Smith via the perspective of her role as a celebrity and how she moved towards her role as a public intellectual. How exactly does she perform these roles? And how does the interplay and transformation between her embodiment of the celebrity and being public intellectual work exactly?

Patti Smith: celebrity vs. public intellectual

Although Patti Smith started writing and making art and is thus initially both author and artist, she first became known for her music. Music was the main part of her accelerated popularity and fame to the general public, in conjunction with her lyrics. According to cultural historian Joe Moran, a celebrity is “well-known for his well-knownness … a perniciously artificial figure produced by the influence of mass media” (Moran, 2000, 2). The public and mass media celebrated Smith, she gained celebrity status and with it more fame in the literary world.

Encouraged by Robert Mapplethorpe, her former lover and lifetime friend, Smith decides to recite some poems on a Tuesday open mic. Later, he arranges for her to open a poetry evening at The Poetry Project as well (Smith, 2010, 177). The decision to have her poems enveloped in guitar music makes the evening a great success. Smith receives all kinds of offers. Initially, she is flattered by all this sudden attention but backs out later. She does not accept any offer, it is all too easy for her (Smith, 2010, 182). Smith deviates here from the idea of the "star author" or "literary celebrity" in which it is purely about the person and not about the art (Moran, 2000, 3). Smith considers her art to be the most important.

Actually, Smith was already showing signs of public intellectual quality long before her current fame and professional career as an artist began. The public intellectual is a frame or a model to give meaning to Smith's functioning in the (media)world, through her activities. When her mother sent her to Sunday school, she read her first verses in the form of prayers. However, dissatisfied with the prayers and getting tired of saying the same phrases over and over, she began to make her own (Smith, 2010, 5).

According to literary and cultural scientist Odile Heynders, who studied public intellectuals in her publication ‘Writers as Public Intellectuals’ (2016) a public intellectual is a “big thinker who knows how to achieve and maintain the attention of his readers, combining economy with cultural history and theory with narrative … one who is capturing the Zeitgeist and personifying it in the right way” (Heynders, 2016, 2). The main features of the public intellectual are “sensitivity, anticipation, the thinking through of alternatives, imagination and courage" (Heynders, 2016, 11). “The intellectual has knowledge and prestige” (Heynders, 2016, 7). These classic conditions of the public intellectual are evident in Smith's life, as she reads her phrases with sensitivity, altering them according to her own insights.

After Sunday school she continued to show signs of the classic public intellectual. Her attention gradually shifted to books, she wanted to read everything, to have knowledge and prestige. Books inspired her and brought new ideas, she thought through alternatives, had the will to express herself, to show herself (Smith, 2010, 6). Smith's intellectual heritage has been very rich throughout her life. Her inspiration ranges from Rimbaud and Baudelaire to Diego Rivera, Cartier Bresson, and Joan of Arc.

Patti Smith: a song and artwork

To illustrate Patti Smith in the light of the public intellectual, I will make use two case studies. The first case concerns a self-portrait with a photo and poem. The second case analyzes the lyrics of the activist song 'People have the Power', written by Smith herself. For the analyses I used the literary music analysis by literary historian Sander Bax in his text ‘Bob freed your mind the way Elvis freed your body’ (2016).

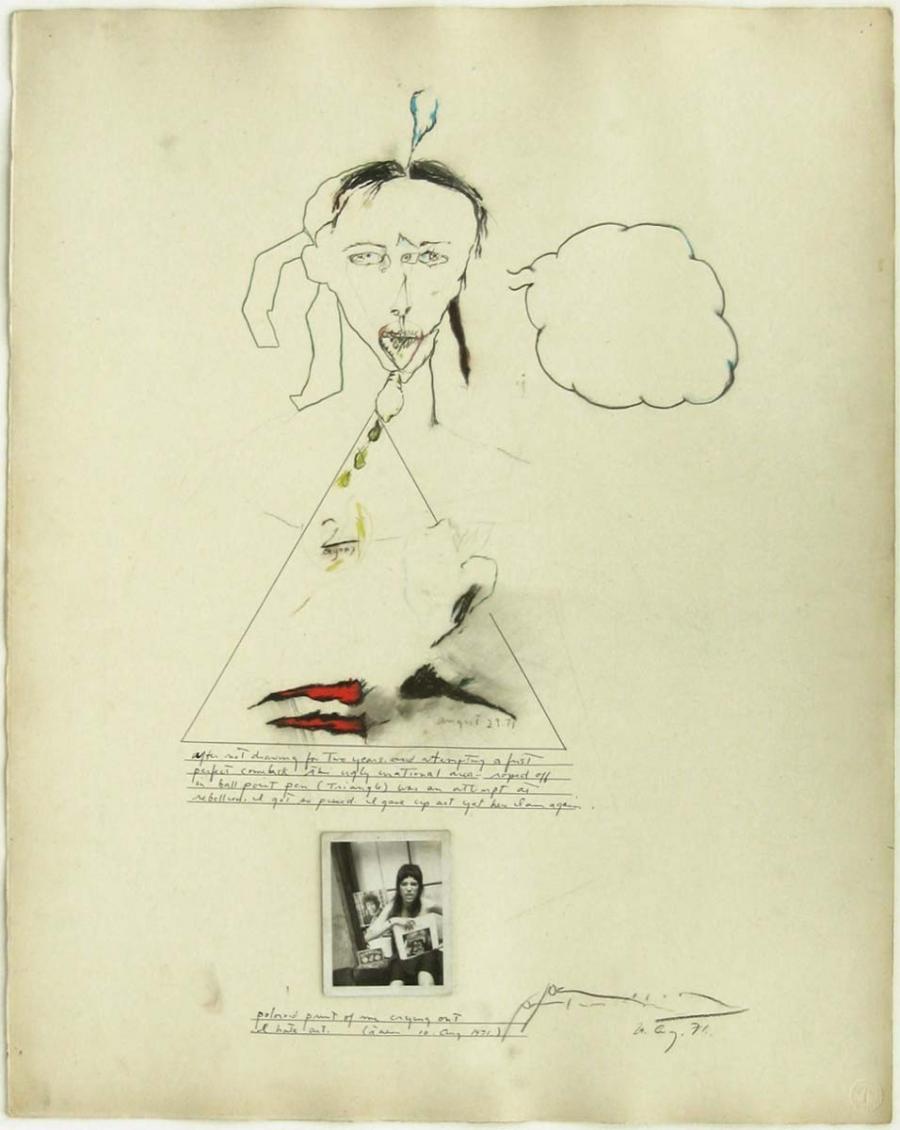

Figure 1: Patti Smith, Self-Portrait (1971), pencil, ballpoint pen, colored pencil, charcoal and gouache with black and white instant print on paper, 73.6 x 58.3 cm., MoMA New York

The written text in the painting is "After not drawing for two years and attempting a just perfect comeback. I’m ugly natural (?) roped off in ball point pen (Triangle) was an attempt at rebellion .... I gave up art yet here I am again" and "Polaroid print of me crying out I hate art … 10 (aug 1971)".

Especially the poem in the painting of Figure 1 reflects parts of the public intellectual character that Smith owns. First of all, I consider this an autobiographical poem as the portrait and the picture beneath it are self-portraits. Secondly, the poem that goes with it is written in the first person as well (Bax, 2016), she writes about herself, like in a diary. She positions herself inside the public intellectual frame as she acts upon the following feature mentioned by Heynders: "The public intellectual intervenes in the public debate and proclaims a controversial and committed and sometimes compromised stance from a side-line position. He has critical knowledge and ideas, stimulates discussion and offers alternative scenarios in regard to topics of political, social and ethical nature, thus addressing non-specialist audiences on matters of general concern" (Heynders, 2016, 3).

Just as Heynders explains here, Smith chooses major themes, like art in this example. In the last sentence, she takes a side-line position and opens the discussion by stating that she hates art, that she gave up art in the first place. Smith points out the ethical and societal discussion about what art is and what art should be. And while it may be unintentional at times and she may just want to challenge or stir things up a bit, she does create commotion, food for thought, and conversation, acting out the role of the public intellectual model. In the poem, no one is personally addressed (Bax, 2016), she addresses everyone who encounters her artworks. Therefore, she is, like a public intellectual, “addressing non-specialist audiences on matters of general concern” as well (Heynders, 2016, 3).

Just like a public intellectual, she takes a political stance here, addressing the people to stand up against and their leaders (the fools)

In the poem, Smith reflects on her current state of mind and the decisions and thoughts she makes and inhabits at this stage in her life. It seems as if she tries to give meaning to herself and to the spirit of the time. She is “capturing the Zeitgeist and personifying it in the right way” (Heynders, 2016, 2). She writes that she has not drawn for two years and has even given up art temporarily. But now, she is very consciously preparing for a comeback.

She describes how, as a rebellious act, she uses the pen as a brush, instead of classic paint, which makes her oppose established art. This is a clear characteristic of the public intellectual frame who is “influencing the public debate with critical statements and provocative ideas expressed in cultural practices providing imaginary scenarios” (Heynders, 2016, 6). And one “who knows how to achieve and maintain the attention of his readers, combining cultural history and theory with narrative” (Heynders, 2016, 2). Like a public intellectual she offers “alternative scenarios” (Heynders, 2016, 3) in regard to societal topics of, in this case, the ethical nature of art. Here, Smith responds to the new role given to the public intellectual in modern society, a role in which Smith not only has (cultural) authority but also values and accepts her audience. The open dialogue that Smith initiates for her audience, with her poem, attests to her desire to have an equal conversation “from speaker to addressee and vice versa” (Heynders, 2016, 12).

When the artist and singer-songwriter Bob Neuwirth asks Smith if she wants to write a song, her role as a public intellectual becomes even more visible. In the days writing this song, she has another performance of the play she has a part in. But the night of the performance turns out to be the night the Kent State Students were murdered. After this evening Smith feels a sense of guilt, she wonders whether the work she does, making art, is the right work. She really wants to be an artist, but she prefers the art she creates to matter more (Smith, 2010, 153).

From this moment Smith's work takes on much more of an activist, political, and therefore public intellectual charge. The song she was writing for Neuwirth became much more activist and turned out to be the first draft of the protest song 'People have the Power'. Just like a public intellectual, she takes a political stance here, addressing the people to stand up against and their leaders (the fools). The sense of guilt she feels while performing and her point of view that it is the art that matters shows her “sensitivity, anticipation, imagination and courage” again, which are all highly important conditions for the model of a public intellectual (Heynders, 2016, 11).

People have the Power (fourth verse):

The power to dream to rule

To wrestle the earth from fools

It’s decreed the people rule

It’s decreed the people rule

I believe everything we dream

Can come to pass through our union

We can turn the world around

We can turn the earth’s revolution

As in the poem accompanying the self-portrait, Smith speaks from the first person in the beginning of the song as well, no one is personally addressed (Bax, 2016), she addresses everyone. Smith is the main speaker and thus the main character of the song (Bax, 2016). She speaks to the people, to all of humanity. It is a monologue addressed to everyone. Later, in the fourth verse pictured above, she speaks from the we-form, which gives a very nice turn because she equates herself with the audience she is addressing. Smith seems to be on the same level as her audience, which harks back to my earlier notion that the public intellectual accepts his or her audience and wants to enter into a dialogue together. She also acts as a kind of spokesperson and formulates, as a true public intellectual, the “interpretations of the identities, interests and needs" (Heynders, 2016, 8) of a social group.

This is visible in the last lines of the fourth verse, which is about a social group tired of war and revolution wanting to chase dreams and as a unity they can actually make these dreams come true like in line six in which Smith sings: ‘can come to pass through our union’. Smith shows with the performance and in the video clip of this song that the idea of the modern public intellectual is not just about a “femme des lettres” and that we must “realise that the persona of the intellectual never is a disembodied one, on the contrary, it is connected to visible individual features and manners” (Heynders, 2016, 15).

If we take a look at what happens exactly in this fourth verse, it starts with having the power, the power to dream and the power to rule. At first glance, this seems to go against the understanding of the public intellectual because the intellectual actually resists power (Heynders, 2016, 10). But Smith is clearly talking about the power of the people, not about the prevailing political power from which she wants to redeem the earth in the second line. She personifies the people she addresses so that she acts as a spokesperson and at the same time forms a unity with them. She is a leader and a follower at the same time. She “addresses an audience while cultivating a position of detachment that increases her awareness of the things going on” (Heynders, 2016, 7).

Smith functions as an “early warning system” taking “stances and expressing them in novel perspectives” (Heynders, 2016, 10). Moreover, this identification and at the same time removal from her public is seen as a characteristic of the modern public intellectual since “public intellectuals today have a different position since they address the public, while at the same time they have become part, and often consciously play to be a part, of the audiences themselves” (Heynders, 2016, 4). Smith, by interacting with her audience in this way, seems to identify as a “collision point, implying that various audiences could project their own ideas upon the intellectual. The public intellectual thus becomes a sort of empty vessel for the public to inhabit with their own ideas” (Heynders, 2016, 5). Smith is not so much concerned with the audience listening to her. The public is free to do whatever they want with her art, or nothing at all.

Patti Smith: the role

The role of Patti Smith is very complex and she certainly does not fully meet the descriptions that belong to the model of the public intellectual and celebrity. She was actually a private author, who no one knew much about. Smith herself always felt that great things were meant for her, that she would one day write a book. But she is also very modest and hardly believes that she is as good as the famous poets she always looked up to. She therefore worked in silence for many years, without even seeking publicity.

It is not about being seen, but about her art being seen

Smith considers herself more author than musician (Independent, 2015). It is not about being seen, but about her art being seen. She is therefore not a standard celebrity, but only a celebrity because others made her that. Not because of her own free will or consent. You see here the common thread with Moran in which he states that a celebrity is produced by context, through the influence of mass media. More or less the same applies to Smith as a public intellectual. She is very much involved in social issues, which is also evident from her writings in ‘Just Kids’.

Smith didn't just develop her public intellectual character herself because she wanted her art to matter, not her person, as a true public intellectual would say and what deviates her from a celebrity. But also partly because of her mother. Her mother was fixated on social issues, which reflected on Smith as well: "I found myself drawn to this story partially due to my mother's fixation on the Lindbergh kidnapping and consistently fear of her children being snatched" (Smith, 2010, 240). But despite this commitment, she does not intend to change humanity and the world, she keeps her own voice without requiring others to take over. Smith is therefore primarily an ethical public intellectual, a more modest public intellectual. She does not want to bother or guide people with her ideas and art, but rather point them out to beautiful things. Her art has no political value but only shows what Smith saw, how she looks, and what she likes, it’s only an invitation to the public. A starting point for the beholder, to do with it whatever they please.

She meets the role of celebrity and public intellectual halfway, which suits her modest character perfectly

Just like the role of the celebrity, the role of the public intellectual is moderately present in Smith's character as well. Certain characteristics are similar, such as her literacy, performances, and ideas, but the core of the public intellectual model that owns a political-economic focus contrasts with the artistic imagination of the world that Smith shows. She needed her celebrity status in order to be able to take over the status of public intellectual as well.

Although Smith occasionally escapes the characteristics of the celebrity and the public intellectual, she still shows that she uses both roles and is actually a floating celebrity/public intellectual, a hybrid. Her actions as a musician, artist, and writer become one in an activist-based practice. She meets the role of celebrity and public intellectual halfway, which suits her modest character perfectly.

References

Bax, S. (2016). Bob freed your mind the way Elvis freed your body. Diggit Magazine. Retrieved from diggitmagazine.com.

Halliday, A. (2019). Patti Smith Sings “People Have the Power” with a Choir of 250 Fellow Singers. Retrieved from Open Culture.

Heynders, O. (2016). Writers as Public Intellectuals. Literature, Celebrity, Democracy. New York. Palgrave Macmillan.

The Telegraph Magazine. (2015). Patti Smith: I am a writer not a musician. Independent. Retrieved from Independent.

Moran, J. (2000). Star Authors. London. Pluto Press.

Smith, P. (2010). Just Kids. Camden. Bloomsbury publishing Plc.