I downloaded six period tracking apps and things got weird

With the rise of smartphones and rapid expansion of mobile networks, there has been a parallel explosion of apps designed to track various aspects of health and fitness. Most new smartphones come with some sort of “health” app already installed, and phenomena such as the quantified self movement - which advocates all encompassing ‘lifelogging’ - have become prevalent. Among these apps are period tracking apps - apps designed to track and analyze your menstrual cycle. These range from simple calendar apps to ones that allow dozens of options for tracking moods, pain, and fertility.

Period Tracking Apps in Context

Self-tracking apps are sites of intense norm production around bodily care and body ideals (Lupton 2017, Lupton & Pedersen 2016). As menstruation is particularly laden with gender norms and cultural taboos, these apps are a significant location for studying digital mediation’s role in creating or contributing to body norms. These technologies are both literal, i.e. devices such as the Fitbit, and technologies of the self in the Foucauldian sense - ways of monitoring the body for social acceptability and correctness.

Lupton (2017) has noted that while there has been a significant amount of market or statistical research on the use of these apps, there is a gap in terms of sociocultural research. This paper thus seeks to be an exploratory review of menstrual tracking apps, and an examination of how the concept of chronotopes can be applied to this relatively new area of study. We will first cover some necessary description of these apps, followed by a discussion of chronotopes in the context of apps and intended users. I will then attempt to deconstruct some of the priorities and norms built into the design of these apps, followed by a contextualization of period tracking apps in the larger context of digital life, data, and privacy.

Branded and Generic Apps

A search for “period tracking app” in the Google Play store returns approximately 250 results. I selected the five most popular/relevant as per Google Play’s search algorithm - My Calendar, My Tracker, P Tracker, Clue and Flo. In my initial survey of period tracking apps, there appears to be two categories: “generic” and “branded” apps. Additionally I included the Eve app in my analysis, as its parent company Glow has attracted some media attention lately and is frequently mentioned in articles about period tracking apps. Because of this, Eve also seemed essential to include in my analysis of “branded” versus “generic” apps.

Branded apps, namely Clue, Flo, and Eve, have attached websites, often with blogs or other informational pages not strictly related to the app itself. Each has some aspect that is emphasized in advertising or in the app description to make it “stand out.” Clue emphasizes the “science” behind the app, and is known for eschewing the pink and pastels common to other apps. Flo more so emphasizes that it can track even irregular periods using AI, and does have a slightly heavier emphasis on tracking ovulation. Eve markets itself as a period tracker that also incorporates tracking and a community around “love, sex and relationships.” Eve’s branding was developed as a “little sister” app to the the company’s original fertility app Glow. The Glow company has also expanded in the opposite direction with the pregnancy tracker “Glow Nurture” and the “Glow Baby” app for tracking infant’s growth and development (it is literally called a “baby tracker” which has all sorts of implications far beyond the scope of this report.)

A branded app can put forth a strong image or agenda - its construction can be targeted at a far more specific end user.

Generic apps are precisely that - generic. My initial survey included the three most popular (as ranked by Google Play) generic apps, namely My Calendar, My Tracker, and P Tracker. Many of them incorporate a flower in their app icon, and while very pink, are ultimately designed to be somewhat “discrete” in terms of what appears on your phone’s home screen. They have no attached websites, and some seem to be produced by “app factories,” companies that turn out a large number of basic health tracking apps. They lack some of the “community” aspects of the branded apps, and some of the ability to customize the app. Interestingly, a few of them seem to “borrow” graphics from each other. My Tracker and My Calendar both feature the same “pets”: small graphics of animals that can be changed out. This mostly seems to be a ploy to get you to watch ads in pursuit of new “pets.” Tapping the pet simply brings you to their data input page.

While both “branded” and “generic” apps are rich in data, there is somewhat of a divergence in what kind of data they provide. A branded app can put forth a strong image or agenda - its construction can be targeted at a far more specific end user. Meanwhile generic apps are designed to appeal to as wide an audience as possible, with the lowest effort on the part of the app designers. Generic apps are more likely to make their money with targeted ads, while some of the branded apps have made promises of data privacy and instead use “premium” models as a source of revenue. Nonetheless, the uniformity among both the branded and generic apps becomes a data point in itself. While of course there are certain constraints to what kind of code you can write or what features are necessary to simply make a functional app, a great deal of data can be derived from what features are considered necessary across a variety of apps. Thus from this point of comparison I began my exploration of how app features construct a chronotope of interaction in period tracking apps.

Chronotopes, Intended Users, and Norm Construction

It is often tempting to see technology as somehow more neutral, or less subject to the whims of social construct, than other aspects of existence. However, van Dijck’s (2013) analysis of social media reminds us that behind any code or algorithm is a human writing it, who brings with them their own sociocultural context. Indeed, beyond this inherent context, apps and social media sites are often designed to function a specific way, with an intended user in mind. While one could argue that sites such as Facebook envision a diversity of intended users, the fact remains that on Facebook you “like” a post, and on Twitter you “favorite” one. By the very nature of their interface each site corrals users, even those not congruent with the anticipated user, into certain patterns of use.

Apps then are attempts to simultaneously anticipate and define a chronotope of interaction. Chronotopes, as used by Blommaert (2015) “refer to the intrinsic blending of space and time in any event in the real world.” It is a way of critically approaching semiotic context. In the realm of apps, the interaction between user and app (and, by extension, programmer) is given parameters within which it must operate via the affordances of the technology. The aspect of technology as mediator is significant here. The relative stability of an app interface introduces a surface level staticness that cannot be relied upon in face to face interaction. Therefore one could argue that through tech mediation there is significantly less space for co-construction in interactions. The relatively static interface of the app then becomes a space for determining modes of interaction on the part of app creators and designers.

This is not to say that technology can completely determine a chronotope. There are always elements of co-construction, whether it be using the affordances of the app in unexpected ways or the fact that apps are, to a certain extent, consumer products. There is no shortage of period tracking apps in the app store, and to a certain extent they must cater to users' expectations in order to be viable. The use of affordances in nonstandard ways is somewhat better documented in social media - consider the example of the Twitter thread. Though Twitter is known for its character limit, and the brevity of communication it was intended to create, users frequently create long “threads” of posts that circumnavigate these limitations. Thus within the chronotope of self tracking apps, we could see similar negotiations of the chronotope.

In the case of period tracking apps, both the function and the appearance of the interface can articulate a very specific kind of intended user.

Self tracking apps, when compared to social media such as Twitter, can afford to significantly narrow down their intended user. For self tracking apps, an intended user is often one that interacts with the app at least daily, believes self tracking to be helpful, and does not question giving up a variety of personal (read: profitable) information. In the case of period tracking apps, both the function and the appearance of the interface can articulate a very specific kind of intended user. In terms of appearance of the app, this normativity starts even from the app’s icon. Pictured below are the icons of the six apps I analyzed for this report. The most striking aspect is the color - almost all of them are some shade of pink. Clue, which deliberately avoids pink branding, is still a bright red. In many western cultures pink is very heavily gendered and strongly communicates femininity. Combine this with the flower imagery of three of the apps and from the start it is apparent that the intended user of these apps is not only female but also culturally, traditionally, feminine.

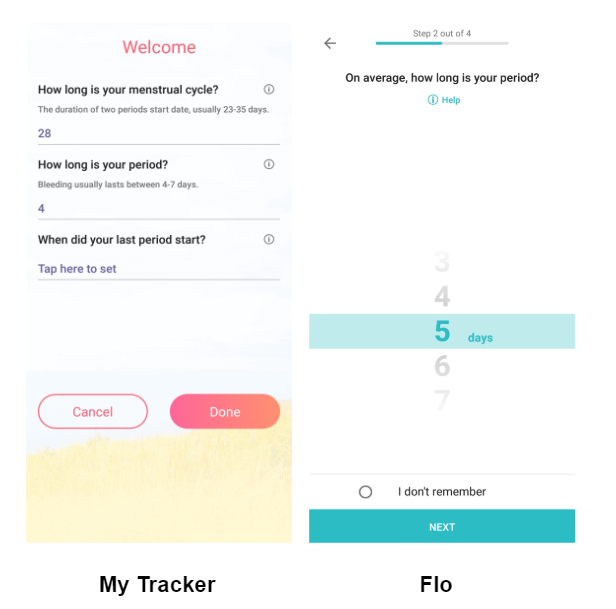

This construction of the intended user continues through the functionality of the app. Each app, upon starting the app for the first time, prompts the user through a set of “onboarding” questions before moving to the normal view of the app. Each of the apps surveyed includes a question on average length of both the period and cycle. However, in every single app this interface starts from a default and then allows you to select from a predetermined range, rather than prompting you to enter a number from your keyboard. This assumes several things about the user: one, that periods are regular (note that one of the examples below is from Flo, which claims to predict even irregular periods), and two, that there is a range, however large (or small) that can be applied to all users. The fact that a default exists at all creates a notion of average or “normal.”

Indeed, however lacking medical research on women’s reproductive health may be, several millennia of experience point to the fact that a significant number of people fall into these average ranges. However, when it comes to apps, many of which are created without the input of researchers or doctors (or women, for that matter), these built in assumptions are in no way neutral or arbitrary. In any sort of self-tracking app, there is self-monitoring both in the Foucauldian and in a very literal sense. Menstruation, in many if not all cultures, is a particular point of intense norm construction, whether these be norms about femininity, health, hygiene, etc. Period tracking apps, by being focused on not just the body but in particular female bodies, thus brings in strong cultural norms around health, and with health comes a strong moral component. When these apps set a default, or provide a range from which you must choose, we are handed a rather tidy guide to what is considered healthy and normal.

Deconstructing App Priorities

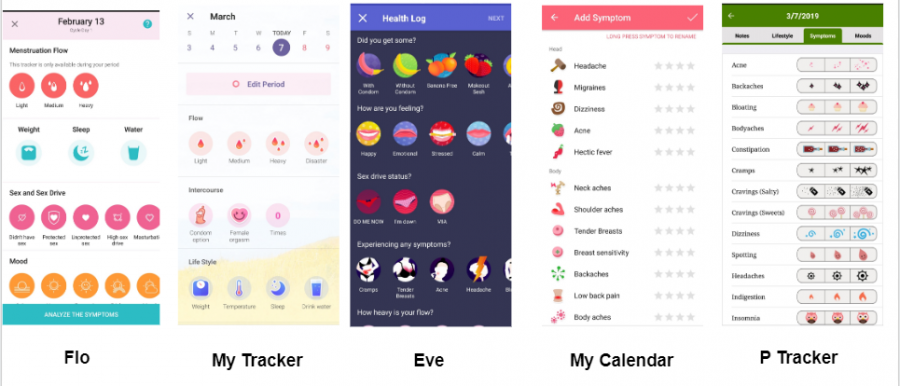

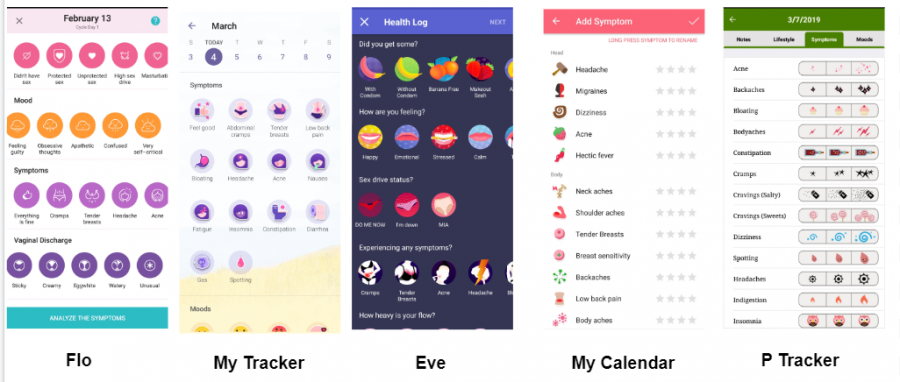

In deconstructing the chronotopes created by these different apps, we can examine not just what norms they reproduce from the larger society, but what are the priorities of this particular app. The example of the “symptoms” or data entry page of these different apps is particularly illuminating:

In comparing the above data entry pages, let’s first take a look at My Calendar and P Tracker. P Tracker organizes symptoms in alphabetical order, while My Calendar organizes symptoms first by “head” then “body” and goes on to “cervix”, “fluid”, “abdomen” and “mental.” In the case of My Calendar, it first appears that symptoms may be organized from top to bottom of the body, but eventually shows very little sign of organization at all. For both of these the most likely explanation for this organization seems to be ease on the part of the app designer.

However, things get a little more interesting when considering the three apps on the left. Both Flo and My Tracker prioritize menstrual flow, but both only show this option when you are expected to be menstruating. The next two options are sex and “lifestyle” trackers. The prioritization of lifestyle trackers suggests that these need to be easily accessible for daily use and are therefore part of the app’s design to elicit as much data as possible - the trackers that will be used most frequently are put front and center.

Beyond what conversations the chronotope of app design allows, we can also look to what conversations are actively encouraged or discouraged.

When considering sex trackers, it is important to note that Eve places this first thing on its data entry page, even above menstrual flow (the option to track that is always present, but does not even make it on to the first full screen). Of course this goes with Eve’s emphasis on “sex, love, and relationships” but also suggests a preoccupation with fertility - or trying to avoid it. As discussed in Lupton’s work, those who are active in the quantified self movement prioritize a sense of self-discovery, of gathering data for data’s sake. The prioritization of sex trackers seems to suggest a context in which tracking for management of fertility precedes any other pursuit of self-knowledge. Beyond what conversations the chronotope of app design allows, we can also look to what conversations are actively encouraged or discouraged.

Even in apps that are aimed at women not trying to become pregnant, these apps often include ovulation predictions - whether in listing your "risk" of becoming pregnant as “high” or in a more neutral tone or positive tone. While Flo markets itself as an ovulation AND period tracker with the expectation that some users are attempting to become pregnant, Eve and Clue do not market themselves as such. However if you look to Eve’s place in the Glow “family” of apps, it does seem to imply that at some point a woman will move on from the Cosmo-esque world of fun and dating to that of stable relationships and motherhood. It seems that many of these apps assume that if not now, at some point users will wish to become pregnant.

It therefore raises the question of how much of this is simply speaking to a consumer want - i.e., there truly is a market for fertility apps - and how much comes from societal norms regarding the progression of women’s lives. Indeed it is probably a feedback loop of sorts. Notably the Glow app has recently begun a cooperation with fertility clinics in the U.S. to promote egg freezing, which opens a whole new avenue of investigation into the commodification of fertility. If anything fertility and motherhood are even more heavily laden with norms than menstruation is, and in conjunction with the fact that many societies are seeing lower birth rates and people delaying having children, how fertility is addressed through these various apps will no doubt have an interesting relationship to changing societal norms.

Medicalization

In the same vein of deconstructing what kinds of conversations a given app allows, the use of the term “symptom” in and of itself is incredibly significant. In western cultures menstruation has been highly medicalized: PMS (premenstrual syndrome) is perhaps the only widely used term in English for the discomfort immediately preceding menstruation. Indeed, I struggled to write the preceding sentence without using the word “symptom.” Medical terminology has become deeply embedded in the way menstruation is discussed, even casually.

Significantly, all of the apps surveyed except one explicitly use the word “symptoms” in their tracking options - referring, presumably, to symptoms of PMS. Ironically it is Clue, the app most focused on the “science” of cycle tracking, that manages to most avoid medicalizing language. One app, Flo, prompts you to “analyze the symptoms” no matter which tracking options you select. For instance, you are given the option to log whether or not you exercised that day. It seems a bit of a stretch to construe doing yoga as a symptom of anything in particular, but nonetheless tracking your day to day life, by its association with menstruation, becomes pathologized.

However, the pathologization of premenstrual experience is still somewhat contested. For instance, PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder), a classification of extreme PMS particularly in terms of mood and mental health symptoms, was recently added to the DSM - 5, and has been highly debated (Browne 2015). Moreover it begs the question of how can we call something that approximately half the population experiences a “syndrome”? Cramping and mood swings are considered normal, perhaps even healthy in that it indicates the menstrual cycle is continuing on as it should. Bringing existing theory on the history of norm creation in medicine as it relates to the pathologization of women’s bodies would no doubt bring valuable insight to how societal norms are replicated and reinforced via these apps, and should be pursued in future research.

Period Tracking Apps’ Place in the Digital Landscape

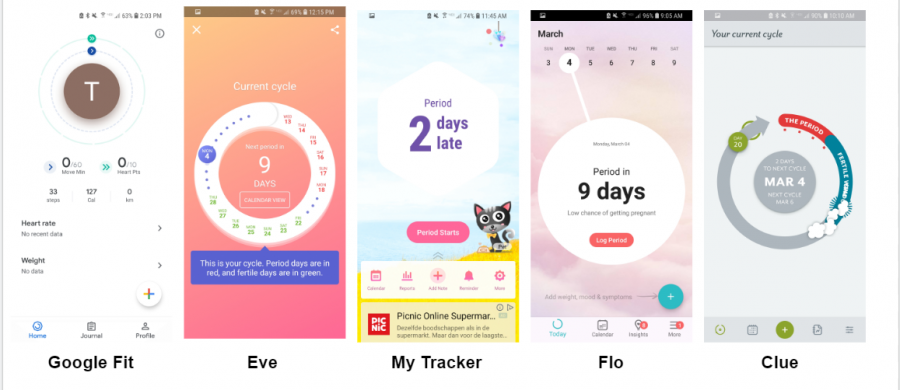

When considering issues of self monitoring in a digital age, it is helpful to contextualize period tracking apps among health tracking apps more generally. Pictured below is the opening page of several of these period tracking apps, compared to the Google Fit homepage on the left. While period apps certainly use circle imagery in light of the cyclical nature of what is being tracked, they also bear a remarkable resemblance to the Google Fit interface. There is a large center button that can be tapped to lead to data input pages, as well as a menu bar across the bottom. This suggests that more can be done to theorize how app interaction is designed in regards to apps that rely on regular data collection.

Self-tracking apps are their own special kind of Foucauldian nightmare

Additionally, self-tracking apps are their own special kind of Foucauldian nightmare. To put it briefly, they are literal self monitoring tools laden with the idea that one can always take better care of oneself. Implicit in this notion is that failing to care for the self is a moral failure. Deborah Lupton’s work on the quantified self movement is perhaps especially helpful here. She makes the salient point that tracking our health - recording exercise, counting calories, and of course period calendars, is nothing new. However in the environment of apps and datafication we are promised that algorithms will tell us something about our bodies that we are incapable of discovering on our own. So at the same time that we are told that failing to care for ourselves properly is a moral failure, self tracking apps offer us a way out of this failure, but at the price of giving ourselves up to greater data collection and commodification of that data.

When looking specifically at period and fertility apps, this data collection becomes more blatantly invasive, and the commodification that much more transparent, as compared to your average exercise app. Period tracking apps collect perhaps some of the most intimate data about our bodies, data that has never before been immediately available to advertisers. While some apps have promised not to sell data directly to third parties, there are just as many running targeted ads. In particular it is widely accepted in marketing that pregnancy and parenthood are a key point in which brand loyalties can be changed and new products introduced. Therefore data gathered from an app that may know you’re pregnant before you do is incredibly valuable.

Returning to the concept of chronotopes, many of these apps’ chronotopes are designed not only to facilitate data gathering but actively encourage it. Each of these apps, unless you go to great lengths to change both the app and your phone’s settings, sends you frequent notifications to add new data. Any time you do choose to add data, the array of tracking options prompts you to log things you might not consider if keeping a pen and paper calendar. Flo even prompts you during its onboarding process to complete a 40-question long health profile. Thus in considering the issues of privacy and data gathering, it is important to consider how these apps are designed not only to elicit the maximum amount of data but also to normalize this disclosure.

Half of a chronotope?

When looking at the design of apps, we can begin to describe the intended chronotope of interaction. Many of the period tracking apps seen here are constructed using societal norms around fertility, medicalization, and gender. While I have spent much of this report detailing how app affordances can determine interaction, we do not know how effective any of this chronotope construction actually is. As noted by Lupton (2016), when it comes to self tracking apps more generally, ethnographic research is scarce. In any interaction with technology there will no doubt be people who rebel against or reappropriate aspects of the design for different uses. Indeed, there is significant research on how social media affordances are constantly taken and reshaped to suit interactional needs. While period tracking apps reproduce a distinct register of societal norms, more research is needed to determine if this register is at all relevant for their users.

References

Blommaert, J. (2015). Chronotopes, scales and complexity in the study of language in society. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies.

Browne, T. K. (2015). Is Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Really a Disorder? Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 12(2), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-014-9567-7

Burke, S. (2018, May 11). Your Menstrual App Is Probably Selling Data About Your Body.

Dijck, J. V. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kresge, N., Khrennikov, I., & Ramli, D. (2019, January 24). Period-Tracking Apps Are Monetizing Women’s Extremely Personal Data. Retrieved March 18, 2019,