Trump, lies, and hydroxychloroquine: a case study

On March 19th, 2020, soon-to-be-former U.S. president Donald Trump endorsed the drug hydroxychloroquine for treating COVID-19 during a coronavirus task force press briefing. Although at the time of the briefing the drug had not been proven effective, and indeed some studies found it might be dangerous, the news went viral both online and through legacy media channels (Hamamsy & Bonneau, 2020).

Trump’s announcement had unintentionally hit on a data void - a search term that has few results, or at least results that search engines deem valuable, associated with it. In the absence of reputable or recent results, it is easy to game search engine algorithms like Google’s. In recent years data voids have been exploited by a variety of groups with less-than-good intentions, including conspiracy theorists and extreme alt-right groups.

In light of a global crisis where there is still very little known about treating COVID-19, any novel treatment announced by a world leader would have attracted massive attention. In the case of hydroxychloroquine, it became the center of debate not just among medical professionals, but also in the media and among average citizens. It became an example of what Venturini (2019) has deemed “junk news” - news that is defined not so much by its relation to truth, but rather by its rapid spread and ability to dominate political discourse even when it has been proven inaccurate.

This article therefore examines hydroxychloroquine as a case study of these two key concepts - data voids and junk news - to demonstrate how they can reinforce and perpetuate one another.

Hydroxychloroquine: a quintessential data void

Hydroxychloroquine is not a new drug. Prior to March 19th, it was well established as a treatment for “uncomplicated malaria, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus” (Harrigan et al., p. 2826). However, it was also precisely that - well established. Chloroquine was invented in 1934 to treat malaria, and hydroxychloroquine was developed several years later as an “alternative with fewer side effects.” At the time of the press briefing, very little new or exciting information about the drug had come out in quite some time, and it was certainly not a hot topic of conversation, even within medical circles.

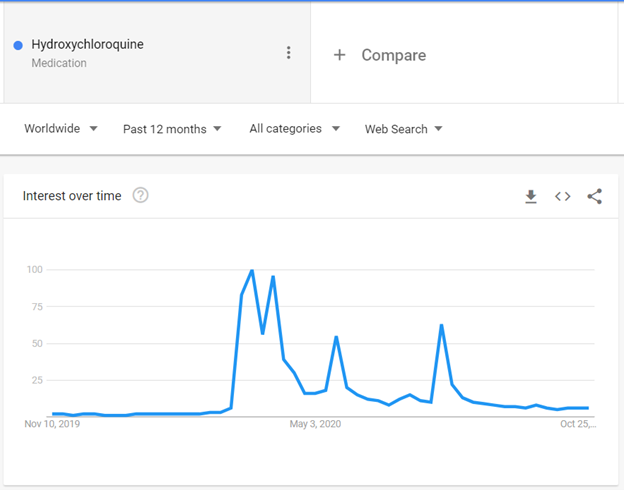

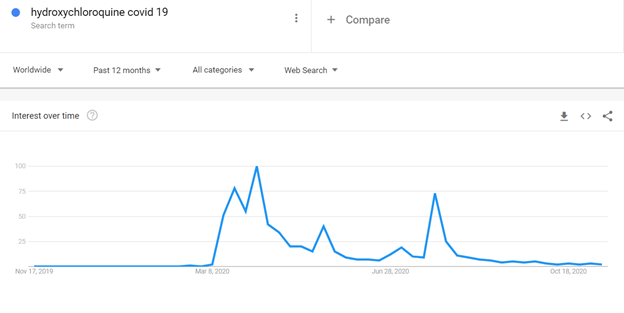

On google trends, we can see that the term ‘hydroxychloroquine’ had a small but consistent number of searches worldwide prior to COVID-19 becoming a full blown pandemic in early March. The search term ‘hydroxychloroquine COVID-19’ had no searches whatsoever before early March, when a few observational studies from China and France were published as pre-prints (i.e., did not undergo peer review)(Sattui et al., 2020). Several of the peaks seen in these graphs can be tied to specific announcements or tweets from Trump, the White House, or, in the case of the final peak, Donald Trump Jr. being temporarily banned from Twitter for sharing a video supporting the drug and making conspiratorial claims.

Search trends for 'hydroxychloroquine'

Search trends for 'hydroxychloroquine COVID-19'

These graphs represent more or less what a data void looks like: a neglected search term that suddenly, and sometimes deliberately, becomes a major point of interest. Golebiewski and boyd explain that “Data voids exist because of an assumption baked into the design of search engines: that for any given query, there exists some relevant content” (2018, p. 16). Search engines like Google will attempt to give some sort of result for almost any search query - only random strings of letters and numbers will stump the algorithm.

Importantly, data voids are incredibly difficult to detect - how do you detect something that’s not there? Further, “Generally speaking, data voids are not a liability until something happens that results in an increase of searches on a term” (Golebiewski & boyd, 2018, p. 2). Even then, an increase in search terms does not necessarily have to have negative implications, for instance in the case of a uniquely named new movie or album. In short, data voids are a ticking time bomb that may never actually go off.

Particularly relevant to the case of hydroxychloroquine is the fact that Google tends to favor new information.

Despite many data voids being (currently) harmless, they can be deliberately exploited. In Maly’s (2019) work on Groypers, the network of radical Christian conservatives deliberately filled the data void around the term “dancing Israelis” with online content about their own anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. They then drew viral attention to the term at a live streamed Q&A with Turning Point USA’s founder Charlie Kirk. By capitalizing on an obscure and rarely-used term, they were able to drive confused viewers to their own web content via Google.

Importantly, during the Q&A a Groyper explicitly instructed Kirk, and by extension all viewers, to “google ‘dancing Israelis.’” This example demonstrates precisely how data voids are a result of our now society-wide dependence on search engines, which are neither neutral nor infallible. We frequently trust Google as a reliable source of information, but it is important to understand that Google’s search algorithm privileges certain kinds of information and tailors that information to individual users. This system has vulnerabilities and, deliberately or not, can become a major concern.

Particularly relevant to the case of hydroxychloroquine is the fact that Google tends to favor new information. Hydroxychloroquine is what Golebiewski and boyd (2018) have termed a “Breaking News” data void. This type of data void occurs when an event, such as a presidential press briefing, suddenly brings attention to a term that has a paucity of search results. In many cases of breaking news data voids, it takes reputable news sources far longer to establish a credible and complete story - indeed it often takes time to get the full details of sudden events - than it does for bloggers and conspiracy theorists to fill the internet with their own interpretations.

This creates a period of time where search engines are prioritizing new information, but none of the new content available is from reliable sources. This is a peak time for conspiracy theories or “fake news” to spread (Golebiewski & boyd, 2018). When searching for hydroxychloroquine, older results may come from more reliable sources, e.g., reputable medical journals or public health information about relevant diseases, but Google’s search results will privilege the most recently updated websites.

In the case of hydroxychloroquine, this gap between a massive upsurge in searches for this term and the emergence of reliable information is exacerbated by the fact that medical science takes time, and the novel coronavirus is exactly that - novel. It is even more difficult for reputable news sources to overcome a data void when clinical trials are still in progress and it is difficult to say for sure whether a treatment is effective or not. Although more information and greater caution about the drug have emerged since March, uncertainty persists.

Viral Spread

Golebiewski and boyd (2018) emphasize that while data voids can somewhat resolve themselves as reliable and more up to date information prevails, “in a breaking news context, the earlier frames can significantly influence public perception.” In an analysis of Twitter activity between February and May 2020, Hamamsy and Bonneau (2020) found that among the hundreds of thousands of tweets about hydroxychloroquine, most of the information shared came from non-scientific sources, and from sources that frequently “spin scientific results.”

Among tweets that shared links, the top ten sources of those links included some reputable news sources, such as the Washington Post, but were predominantly right wing or far-right sources, such as the Gateway Pundit and Breitbart (Hamamsy & Bonneau 2020). As late as September 2020, for example, the Gateway Pundit was still promoting hydroxychloroquine as a safe and effective treatment for COVID-19, at a point when it had been largely deemed ineffective or even potentially dangerous by further medical trials.

In the Google trends graphs above, the final peak in searches for hydroxychloroquine can be tied to a viral video that emerged in late July, of a group of alleged doctors insisting that hydroxychloroquine was safe and effective, and that masks were not effective in preventing the spread of COVID-19. While the video was quickly taken down by major social media platforms, and Donald Trump Jr. was even briefly banned from Twitter for resharing the video, it demonstrates both an adherence to President Trump’s assertions and the persistence of certain information long after it has been proved inaccurate.

United States of Junk

Perhaps under a different president, doctors and researchers would have used the emergency authorization to use hydroxychloroquine to continue quietly testing it. Under the media attention to Trump’s frequently inaccurate statements, and his subsequent doubling-down on hydroxychloroquine as a miracle cure on Twitter, however, the issue continued to pop up in public discourse throughout the summer.

While much of this was driven by Trump himself, Golebiewski and boyd argue that “even headlines intended to negate rumors can help spread them” (p. 21). For every presidential tweet, there was a corresponding media response intended to debunk or at least mitigate the effects of that tweet. While it is easy to call many of the claims about hydroxychloroquine “fake news”, the term does not accurately encapsulate the sort of call-and-response that leads to inaccurate claims dominating news media.

Venturini (2019) instead proposes the term junk news. While “fake news” has become a somewhat empty term often lobbed at one’s political opponents, Venturini argues that the significance of fake news is not its truth or falsehood, but rather that it spreads so rapidly and dominates the conversation, “leaving little space to hear other discussions, reducing the richness of public debate and preventing more important stories from being heard.” This phenomena is exacerbated by the fact that many legacy media now report on social media phenomena - especially when the U.S. president is tweeting (Chadwick et al., 2016).

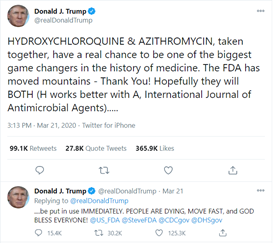

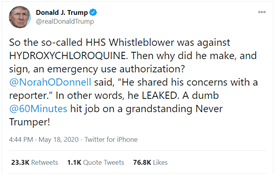

Although the clamor over hydroxychloroquine started in an official press briefing, the party continued on Twitter, with Trump declaring the drug a “game changer” several days later. Trump then continued to insist on the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine throughout the summer, despite evidence to the contrary and criticism from medical researchers (Cortes-Penfield, 2020; Sattui et al., 2020).

Trump tweet from March 21, 2020

Trump tweet from May 18, 2020

Trump tweet from July 7, 2020

Venturini argues that junk news is a product of the attention economy - the idea that even legacy news media, which now primarily operates online, is competing for attention and therefore advertising revenue. Junk news is therefore not necessarily what is newsworthy or valuable to public debate, but rather whatever news grabs the most attention. While the statements of the U.S. president are, arguably, newsworthy, in the case of hydroxychloroquine Trump’s overly confident assertions are often more attention grabbing than a collection of conflicting medical studies that cannot offer a miracle cure.

Importantly, Altheide (2020) found that “Only about a third of voters who have seen his tweets get them directly; nearly three-quarters learn about them from TV and cable news” (p. 518). Legacy media, even when they are attempting to debunk false assertions about hydroxychloroquine, unintentionally bolster its place in public discourse.

Real world consequences

While this article has primarily focused on analyzing the mechanics of data voids and junk news, it is important to understand their “real world” consequences. As a result of the press briefing and subsequent media storm, some places in the U.S. faced shortages of the drug, impacting access for those using it for chronic conditions such as lupus (Sattui et al., 2020).

Further Harrigan et al. (2020) found that “The US administration’s endorsement of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 was associated with an abrupt increase in the rate of prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine” and that this “suggests that Presidential endorsements can influence prescription practices, even in the absence of high-quality evidence or US FDA approval for the given indication” (p. 2826-7).

The confusion resulting from the hydroxychloroquine data void, as well as the intense attention brought to Trump’s assertions via a surfeit of junk news, had a large and serious impact on the American healthcare system. At this point it is difficult to determine how many patients may have been negatively impacted by unproven treatments.

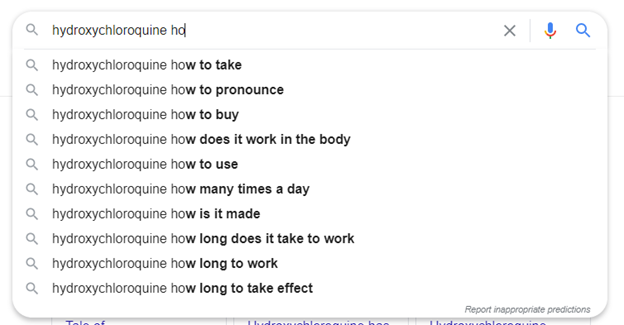

Even more difficult to track, however, is the long term impact of conspiracies and misinformation about hydroxychloroquine. It is known that at least one man has died after attempting to prophylactically take chloroquine by ingesting an aquarium cleaning agent of a similar name (Shepherd, 2020). As of November 2020, a Google search for hydroxychloroquine, done with a VPN to minimize personalization, still offers the following autocompletions:

Google's autocompletions for the search term 'hydroxychloroquine'

While it is of course possible that some of these are quite innocuous or reflect searches from patients who are legitimately prescribed the drug, it does seem to imply that more than a few people are attempting to self-medicate themselves for COVID-19.

A Systemic Problem

Hydroxychloroquine is unique as a data void because even after the initial void in search results was resolved, the knowledge void, i.e., the need for continued testing and clinical trials of the drug among COVID-19 patients, persisted. What could have been solely the concern of doctors and medical researchers became a focus of international media attention and a flash point of misinformation and public debate.

Importantly, the pervasiveness of junk news, and indeed attempts to debunk false claims, perpetuated the attention to the knowledge void long after the data void had been somewhat resolved. While we can blame Trump for continuing to make false medical claims and encouraging conspiracy theorists, we can also look to news media that now feeds on his every tweet to maintain public attention.

Data voids present a major issue and security concern not just because of the algorithmic mechanics of search engines, but because our news, online information seeking, and the proliferation of misinformation are now deeply intertwined. A culture of junk news not only perpetuates attention to data voids, but also makes them more dangerous in the first place by giving more space to potentially false information.

Golebiewski and boyd (2018) argue that because data voids are so unpredictable, mitigating their impact is a matter of search engines (and by extension social media) consistently monitoring and managing them. While this is a sisyphean task, tackling junk news is even more so. Debunking rumors is potentially as irresponsible as ignoring them. The best response to junk news may not have to do with the news at all, but may instead lie in creating greater media literacy and encouraging critical thinking when engaging with online information.

References

Altheide, D.L. (2020) Pandemic in the time of Trump: Digital media logic and deadly politics. Symbolic Interaction, 43(3), pp. 514-540.

Blair, E.A. (2020, September 8). Hydroxychloroquine reduces risk of death from COVID-19 by 30%, latest Italian study shows. The Gateway Pundit.

Cathey, L. (2020, August 8). Timeline: Tracking Trump alongside scientific developments on hydroxychloroquine. ABC news.

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., Smith, A. (2016). Politics in the Age of Hybrid Media: Power, Systems, and Media Logics. In A. Bruns, G. Enli, E. Skogerbo, A.O. Larsson, & C. Christensen (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Routledge.

Cortes-Penfield, N. (2020, April 9). A critical examination of the controversial study behind hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for COVID-19. University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Data Void. Diggit Magazine.

Frenkel, S. & Alba, D. (2020, July 28). Misleading virus video, pushed by the Trumps, spreads online. The New York Times.

Golebiewski, M. & boyd, d. (2018). Data voids: Where missing data can easily be exploited. Data & Society.

Hamamsy, T. & Bonneau, R. (2020). Twitter activity about treatments during the COVID-19 pandemic: case studies of remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, and convalescent plasma. medRxiv (preprint).

Harrigan, J.J., Hubbard, R.A, Thomas, S., Riello, R. J., Bange, E., Mamtani, M. & Mamtani, R. (2020). Association between US administration endorsement of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 and outpatient prescribing. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(9), pp. 2826 - 2828.

Maly, I. (2020, March 24). The coronavirus, the attention economy, and far-right junk news. Diggit Magazine.

Maly, I. (2019, April 11). Charlie Kirk’s Culture War, Groypers, Nickers and Q&A-trolling. Diggit Magazine.

Rowland, C. (2020, April 6). Why does Trump call an 86-year-old unproven drug a game-changer against coronavirus? The Washington Post.

Sattui, S.E., Liew, J.W., Graef, E.R., Coler-Reilly, A., Berenbaum, F., Duarte-Garcia, A., Harrison, C., Konig, M.F., Korsten, P., Putman, M.S., Robinson, P. C., Sirotich, E., Ugarte-Gil, M.F., Webb, K., Young, K.J., Kim, A.H.J., & Sparks, J.A. (2020). Swinging the pendulum: lessons learned from public discourse concerning hydroxychloroquine and COVID-19. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology, 16(7), pp. 659-666.

Shepherd, K. (2020, March 24). A man thought aquarium cleaner with the same name as the anti-viral drug chloroquine would prevent coronavirus. It killed him. The Washington Post.

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. (2020, March 19). Remarks by President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Members of the Coronavirus Task Force in Press Briefing [Press Briefing].

Venturini, T. (2019). From fake to junk news, the data politics of online virality. In D. Bigo, E. Isin, & E. Ruppert (Eds.), Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. Routledge.