#BodyPositive: Disrupting Normativity Online

The hashtag #bodypositive has now been used by more than 4 million people on Instagram, in posts that include selfies and memes both in support of and against the movement. Slater et. al (2017) define a positive body image as “a multi faceted construct that incorporates an overarching love and respect for the body”, while activists say that “the body positive movement uses rhetoric rooted in empowerment to affirm women of size and encourage us to accept ourselves as we are, regardless of our dress size" (Dionne 2017). This paper will use a Foucaultian lens to explore how body positive Instagrammers use selfies and memes and appeals to an increased authenticity to counter normative discourses of the body in western societies.

Over the past several years, much ado has been made over the impact of social media on the body image of young women (Slater et. al., 2017; Feltman & Szymanski, 2017; Burnette et al., 2017). Indeed, “Social networking services are now more popular than conventional media formats among young women, with 90% of 18-29 year old women reported to be active users of social media” (Slater et al., 2017: 87).

Despite a recent report by the American Psychological Association that “American women’s (and men’s) dissatisfaction with the skin they’re in began to decline to the early 2000s,” some research shows that viewing images on social media - even with the knowledge that they are heavily edited - may negatively impact self-esteem and body image, particularly for young women (Schrieber & Hausenblaus 2017). Into this milieu came the #bodypositive movement, a phenomenon that has its roots in offline activism for greater acceptance of all bodies.

#bodypositive: Love Your Self[ie]

A key piece of the body positive movement’s presence on Instagram is selfies. While selfies have been widely criticized as expressions of vanity and narcissism, the body positive movement utilizes them to challenge and subvert body norms in western societies. Indeed, Maddox (2018) argues that they give “selfie-takers...agency and control in their own image production because they are no longer relying on an extra person (or, outside photographer) to take the picture for them...With this elimination, the image in the photograph (the individual) subverts the power structures normally accompanied by photography…” By taking control of their own image, the agency afforded by selfies serves to empower the selfie-taker.

What's more, within the body positive movement, these “subversive” images are an attempt to counter normalized images of bodies both in traditional mass media and on digital platforms. Maddox (ibid) further notes that “The selfie is a way to negotiate between lived experience and mass media. With control in the selfie-taker’s hand, concepts such as racial and sexual stereotypes, as well as unrealistic body images (among many other tropes) become less a part of said individuals cultural footprint.”

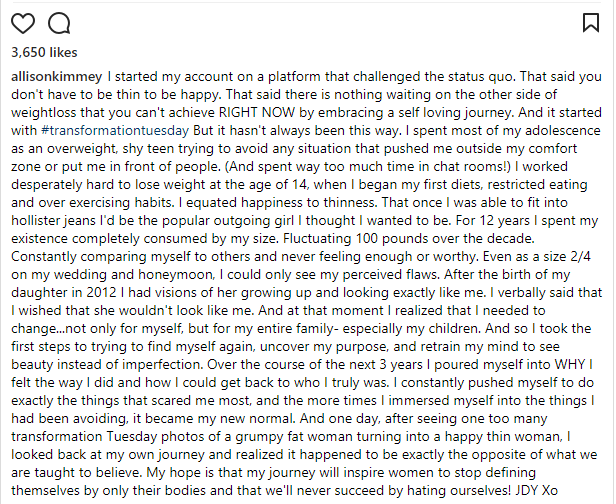

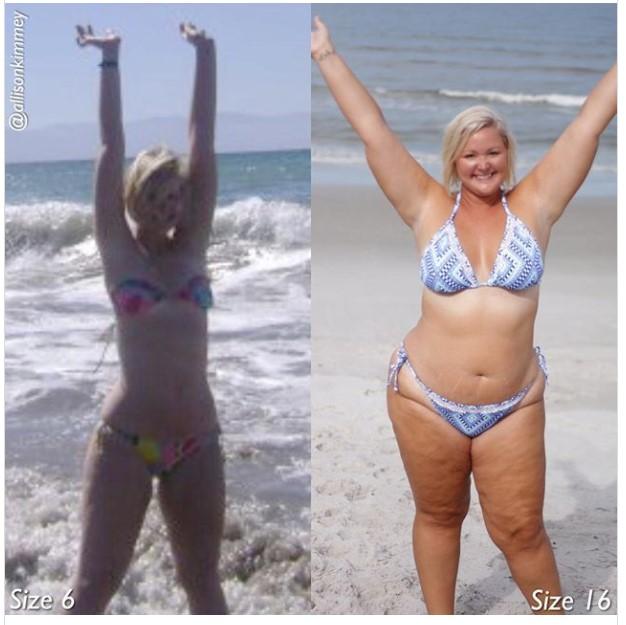

The inversion of the before and after photo subverts a culture of self-monitoring and attempts to replace it with a culture of self-acceptance.

One common trope among body positive Instagrammers is to invert the “before and after” photos associated with dieting advertisements. In these images, the photo on the left is typically the “before”, while the photo on the right is typically the “after.” That is, before and after following a diet or exercise regime, with the images designed to show the efficacy of these programs. Pylypa (1998) writes that “Foucault argues that power produces the types of bodies that society requires. Fitness and dieting create disciplined bodies appropriate to the capitalist enterprise -- productive, controlled, habituated to external regulation and self-restraint.” Moreover, she argues that “Power came to operate by the creation of a desire to achieve the “perfect body” through such disciplinary practices as physical fitness activities and the monitoring of body weight” (27). As such, traditional dieting “before and after” photos can be interpreted as expressions of capitalist and patriarchal power that encourage self-monitoring.

While designed to show that a given diet program “works”, these images also send a variety of other messages - perhaps most importantly that if you look like the “before” image, then you are socially unacceptable, and must take steps to look like the “after” image. In attempting to dismantle societal expectations surrounding bodies, body positive Instagrammers use the before and after format to take the opposite position, framing “unacceptable” bodies as good and encouraging the normalization of these bodies.

Many of these Instagrammers are in recovery from eating disorders, and in contrast to diet ads and other societal pressures, these photos display pride in recovery instead of pride in “achieving” the “perfect body.” The inversion of the before and after photo subverts a culture of self-monitoring and attempts to replace it with a culture of self-acceptance.

Interestingly, many body positive Instagrammers make the important distinction that one of these bodies is not inherently “better” than the other, rather that it is better distinctly for that individual. Above, we see an example from Instagrammer @bodyposipanda, displaying on the left a “before” and on the right an “after” photo, with the “after photo” proudly showing off tummy rolls and bigger thighs. One could interpret the image as glamorizing only the right-hand photo.

Indeed, the second photo is better lit and features the subject smiling widely. However, the first line of the caption is: “Neither of these bodies is better than the other.” She goes on in the second paragraph to elaborate on how the second body is better for her own personal happiness, due to no longer suffering from her eating disorder and obsessive dieting. In further subverting the “before and after” photo trope, she privileges individual contentment over societal expectations.

Appeals to Authenticity

Outside of subverting certain tropes, body positive selfies counter normativity through an appeal to authenticity. Indeed, it is not sufficient to simply be normal, but one must be authentically so (Varis & Blommaert 2015). This is especially true of body positive Instagrammers based in the United States; a highly individualized culture that emphasizes “being yourself” within a certain set of societally determined parameters. When analyzing these posts, it’s important to look at the text captions as well as at the photos themselves.

Here, we have another use of the reversed before and after picture, by a body positive Instagrammer that briefly went viral in 2017. While shorter captions may be more common on Instagram, several body positive Instagrammers we encountered favored long, narrative captions, mostly featuring personal stories and explaining the significance of the photo above. It is a presentation of honesty and vulnerability, countering societal sanctioning of their bodies with a forthright display of authenticity.

Memes for #BodyPositivity

Aside from selfies being an important component of the body positivity movement online, other phenomena, such as memes, also contribute significantly to the movement. In this day and age, memes are made of every single topic, both positive and negative. This includes the body positivity movement. The movement uses/alters memes to fit them into the context of body positivity and to further undermine societal expectations of the way a body should look by mocking these notions.

In essence, they are going against the concept of normativity that society promotes. Furthermore, memes are also used so people could relate to one another. As Shifman explains, “Internet memes are defined here as units of popular culture that are circulated, imitated, and transformed by individual Internet users, creating a shared cultural experience in the process” (Shifman 2013). Thus, memes are used as tools to increase the visibility of body positivity and its acceptance, as they are one of the most effective methods of sharing information online nowadays. However, one shouldn’t overlook that with more visibility comes potentially more negativity, and thus there are also numerous memes made against the movement.

Instagram accounts dedicated to the body positivity movement, such as @bodypositivememes, use various types and styles of memes, from using existing formats of memes to creating new ones. Each of them is aimed at countering normativity in society and societal views. An example of a meme made by using an already existing format can be seen above. Here you can see classical art being used as a meme, with the text referring to what each figure in the portrait is supposedly saying. This meme subverts the societal narrative of ‘being fat means that you can’t be beautiful’, i.e. that you could only be one or the other. This meme implies that one could indeed be both. The number of likes and comments on this post reflects the relevance and influence such accounts and this particular post have.

The above is another example of a meme, using an entirely different format. This meme makes use of a scene from a film, which is then repurposed for the context of body positivity. In the meme, the woman is being asked ‘who her lover is’ and she replies, "myself". This embodies what the body positive movement stands for: self-love and acceptance over societal norms.

Additionally, some studies have found that memes such as this can also lead to an increase in women accepting themselves the way they are. Slater et. al (2017) state that “Compared to women who view neutral images, women who viewed self-compassion quotes on Instagram reported greater body satisfaction, body appreciation, and self-compassion and lower negative mood”. This meme acts as a ‘self-compassion quote’ to which many viewers can relate. Furthermore, this meme tackles societal body norms by appealing to authenticity. By reinforcing ‘self-love’ through this meme, it implements the idea of loving yourself the way you are. Thus, this tackles normativity in society which requires individuals to obsessively self-monitor for things that are 'wrong' with them.

Body Negativity in the Eyes of Society

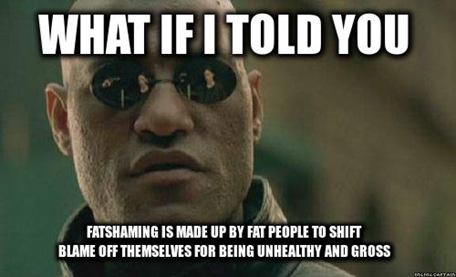

The popularity of the online body positive movement has increased over the years, and naturally there have been negative reactions as well as positive. Negative reactions have been communicated through memes as well. An example of a meme against the movement can be seen above. An old format of a meme is being altered here to communicate the message. This meme uses a scene from the film The Matrix, where this character informs others about the “true” nature of reality.

Thus, by using him, this meme implies that whatever the text says is the ‘truth’; indicating that people who are against fat shaming are just trying to avert blaming themselves for being unhealthy. So, by being unhealthy they are abnormal in the eyes of people who live in a society that promotes healthiness (Foucault, 2003). By referring to them as unhealthy, society categorizes them negatively, which results in these memes being created against body positivity. `

Furthermore, online body positivity also destabilizes the power structure of society, where ‘the goal is to be healthy (read: thin)’. Additionally, Foucault explains that ‘Health is also a moral thing’ in society; being unhealthy means that you are easily threatened by desire, which refers to weakness. In this case, desire can be related to laziness, overeating etc. Thus, if we easily succumb to our desires we are weak and we will not be healthy and ‘if we aren’t healthy, the rest of society will suffer’. This fuels people to position themselves against these movements as they represent abnormality and weakness, which is unacceptable in society.

Body positivity Instagrammers have tackled body norms in society quite successfully, despite the backlash they have received online.

In conclusion, body positivity Instagrammers have tackled body norms in society quite successfully, despite the backlash they have received online. By appealing to authenticity through selfies with genuine captions and unedited photos, body positive Instagrammers have managed to make the movement grow. This becomes evident through the large number of posts under the hashtag #bodypositivity, and the number of followers and likes accounts related to it gain.

Thus, as the movement grows, their goal of acceptance, which counters the traditional goal of society of being ‘slim’ and therefore ‘healthy’ gains more attention, too.

Furthermore, the use of memes has been beneficial to the tremendous growth of this movement as well, as memes are the most successful way to appeal to different audiences. Even though there have been increasing amounts of negativity in the form of memes against the movement, the positivity outweighs the negativity. The negativity also represents the part of the population that is ‘normal’. Nevertheless, through genuineness and authenticity, Instagrammers have helped an offline movement grow online and have magnificently tackled normativity in society both online and offline.

References

Burnette, C. B., Kwitowski, M. A., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2017). “I don’t need people to tell me I’m pretty on social media:” A qualitative study of social media and body image in early adolescent girls. Body Image, 23, 114-125. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.001

Dionne, E. (2017, November 21). The Fragility of Body Positivity: How a Radical Movement Lost Its Way. Retrieved April 23, 2018

Feltman, C. E., & Szymanski, D. M. (2017). Instagram Use and Self-Objectification: The Roles of Internalization, Comparison, Appearance Commentary, and Feminism. Sex Roles, 78(5-6), 311-324. doi:10.1007/s11199-017-0796-1

Foucault,m (2003). Abnormal. Lectures at the College de France 1974- 1975.

Maddox, J. L. (2018). Fear and Selfie-Loathing in America: Identifying the Interstices of Othering, Iconoclasm, and the Selfie. The Journal of Popular Culture, 51(1), 26-49. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12645

Pylypa, J. (1998). Power and Bodily Practice: Applying the Work of Foucault to and Anthropology of the Body. Arizona Anthropologist, 13, 21-36. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

Schrieber, K., & Hausenblaus, H. (2016, August 11). What Does Body Positivity Actually Mean? Retrieved April 23, 2018

Shifman, L (26 March 2013). Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12013

Slater, A., Varsani, N., & Diedrichs, P. C. (2017). #fitspo or #loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram images on women’s body image, self-compassion, and mood. Body Image, 22, 87-96. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.06.004

Varis, P., & Blommaert, J. (2015). Enough is enough: The heuristics of authenticity in superdiversity. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 4-15. Retrieved April 23, 2018