Twitter threads and supervernaculars

In this article I seek to examine supervernaculars through a case study of "Twitter threads." Blommaert (2011) describes his concept of supervernaculars as semiotic codes and systems that function outside of traditional, geographically based speech communities, driven by new technologies. Through a brief history of "Twitter threads" and an analysis of how they have developed in response to both changing platform culture and changes to the platform itself, I aim to explore Blommaert's concept.

A Brief History of Twitter Threads

Twitter has undergone many changes to its interface since it was launched in 2006. Despite the most recent update to allow 280 characters per tweet (formerly 140), one feature that has remained constant is that the site limits the amount you can communicate in a single tweet. However, that never managed to stop anyone from saying as much as they please on the site – conventions quickly developed around allowing users to communicate longer thoughts and expressions to their followers. While the “micro” in Twitter's self-described microblogging platform limited the vehicle through which you could communicate, they failed to put a cap on users’ creativity. With no limit on the number of tweets a certain user could produce, these mini-essays could potentially be hundreds of tweets long (but generally are more in the 5-20 tweet range). These came to be known as “threads.”

With no limit on the number of tweets a certain user could produce, these mini-essays could potentially be hundreds of tweets long.

Today, following several recent updates, users are able to “thread” their tweets by replying to their own tweets in order – thus creating a series of tweets that are connected using the available interface. However, this has not always been the case. Prior to an update in March 2017, a reply tweet would by default include “@username” at the beginning of the tweet, cutting into one's precious 140 characters (Lee, 2017).

Even prior to that, the site’s initial launch did not include a reply function at all (Weller et al., 2014). Thus a convention arose around numbering your tweets, so that followers may determine the proper order in which to read them. Typically one would end each tweet with two numbers with a slash between them, e.g., “1/5”, indicating that you had just read the first of five ordered tweets. However the second number was quickly dropped in cases where the user did not wish to limit themselves to a certain number of tweets – e.g., “1/?” or simply “1/”.

As the convention developed, the ordinal was moved to the beginning of the tweet, indicating to potential readers at the outset that they could skim over the tweet if they were not ready to become invested in a potentially long thread.

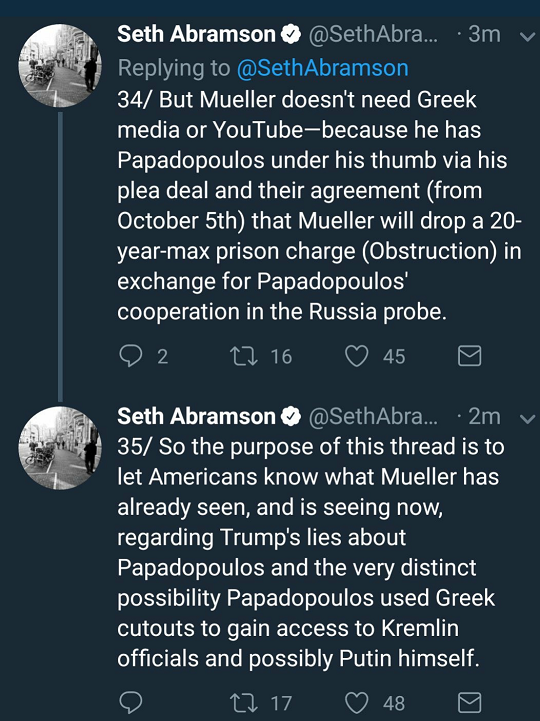

As we can see in the example below (regarding accusations of the current U.S. administration colluding with Russia), these Twitter threads could often be quite long, even over 100 tweets as with this thread in which a twitter user explained in depth her theory regarding the popular television series Friends.

Following the March 2017 update, usernames could be removed from the reply, and further it was later removed altogether and moved into a space above the tweet when viewed independently in your Twitter feed (Lee, 2017). Again users adapted to the interface – or, rather the changes to the interface were Twitter’s response to the ways in which users consistently create work arounds and ways of communicating how they want, often in spite of the interface (Weller et al., 2014; Van Dijck, 2013).

Over the years Twitter has implemented a number of changes to its interface that arose from users' workarounds (Weller et al., 2014). In the first few months following the update, users began to drop the ordinal in threaded tweets, instead replying to their own tweets, in sequence. For example: the second tweet in a series is written in a reply to the first, the third written as a reply to a second, etcetera. Twitter lacks “nested” replies (i.e., each reply is indented below what it is in response to, indicating to the reader what specifically is being commented on and in what order) that are used by many message boards, such that replying to ones’ own tweets creates the same vertical thread as a series of independent tweets would.

Additionally, Twitter has recently experimented with displaying the first few tweets of a thread grouped together in your feed. Typically one has to click through a tweet in order to view replies.

Almost all social media platforms have gone through cycles of platform shift and user protest.

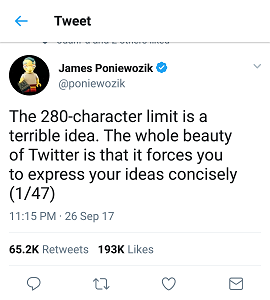

Twitter's most recent update, rolled out in November of 2017, allows users up to 280 characters in their tweets, as opposed to the once-iconic 140 characters. There was initially a great deal of discussion and debate regarding the update, repeating a pattern of adaptation, change, and resistence that Van Dijck (2013) has documented through her analysis of various social media platforms in The Culture of Connectivity.

Almost all social media platforms have gone through these cycles of platform shift and user protest. The implementation of the "timeline" feature on Facebook even prompted many users to permanently leave the platform (Van Dijck, 2013). For Twitter, many users felt (or sometimes hoped) that longer tweets would eliminate Twitter threads.

While social media platforms are sites of constant change, and I have not been able to fully explore the effects of the update as of now, anecdotally I have found that the presence of threads has not decreased. Instead tweets that utilize the full 280 characters have taken on a different tone and role altogether in Twitter's discourse.

Hidden Supervernaculars

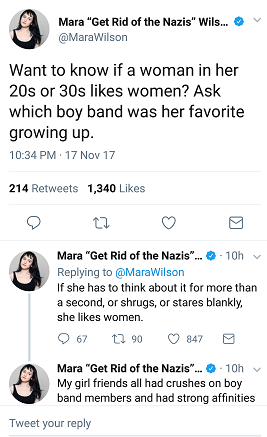

Below I have two examples of post-update Twitter threads, one explicitly marked “thread” and one which is not. For context, both of the “tweeters” here are American actors known for being vocal on social media about social justice issues.

What is interesting about these two tweets, and indeed what sparked the idea for this paper, is that I instantly recognized that the second tweet was the beginning of a thread. While it is a declarative statement, in Twitter parlance it is not a complete thought. If anything it reads like the opening line of a magazine article. The changes and developments in how Twitter users “thread” their thoughts is not merely a response to changes in the platform, but also includes an organic acculturation to communication patterns and conventions specific to Twitter.

Here is where we begin to see a deeper dimension of what Blommaert describes as a dialect of a supervernacular – though Twitter operates overwhelmingly in English, it is a far cry from the imagined “standard” English, and acquires the ‘’accent” unique to the sociocultural communication community that is Twitter. These semiotic conventions go much deeper than the obvious, i.e., marking your tweets with "thread." Here we see a differentiation through relatively "normal" English between two types of communication on Twitter - standalone tweets and threads. The community is slowly losing the need for thread markers not just because of changes to the platform but because certain norms have become rather deeply entrenched.

Especially within the context of social media, what we actually have are not full-fledged languages, but rather pidgins.

Blommaert has described his supervernaculars as “mini languages” or “dialects.” However, I would argue that especially within the context of social media, what we actually have are not full-fledged languages, but rather pidgins. Linguistic and communicative systems cobbled together from the language resources available, functioning and flowering within a confined (and in the case of Twitter, contrived) situation. We cannot divorce the linguistic forms that have developed on Twitter from the codes and algorithms that govern the site. Gershon elaborates:

“The structure of a technology helps to shape the participant structure brought into being through its use, simultaneously enabling and limiting how communication can take place through that medium, how the communication circulates, and who can participate.” (2010, p. 285)

Further, the two languages being blended are organically human (most often some variant on Blommaert’s various world “englishes”) and machine – the algorithms and codes that make the communication technology possible.

Co-construction

As I have shown with the development of threading conventions over time and in response to platform updates and changes, Twitter’s supervernacular/pidgin is rather fluid, not unlike languages used in more ‘’traditional’’ or geographically based language communities. Much how “google” or “tweet” became verbs in American English, Twitter's supervernacular changes in response to societal and technological shifts.

However, this does not mean that these changes, whether in online or offline language communities, happened seamlessly and without challenges. Communication conventions on Twitter are mutually constructed by users in tandem with the constraints of the platform, and are often contested by users. Additionally, the breaking (or bending, or stretching) of established norms can result in policing by community members:

Despite the almost infinite possibilities of Twitter threads, socially speaking, there is a limit to what is an acceptable length for Twitter threads. Here we see the same thread from earlier (the one theorizing about issues in the current U.S. administration), screenshotted and posted in a new tweet, reprimanding the poster of the original thread. The fact that the thread was screenshotted and not replied to is significant in and of itself, but is beyond the current scope of this article. A brief jaunt to the screenshotted Twitter user’s profile page shows that he is a professor widely known for his overly long Twitter threads, which some users praise while other users scold. Thus, not just the conventions surrounding organizing your Twitter threads, but the nature of the thread as a communication form is something that is negotiated and constructed by the online community.

Further Blommaert, in describing supervernaculars says that,

“sociolinguistically they operate in a very different way, not predicated on the traditional connections between languages and speech communities described earlier, and determined (in the strictest sense of the term) by new information and communication technologies.” (2011, p. 5)

I find Blommaert’s “strictly” determinist attitude towards technology a bit too much, as even in offline communication, dialects and linguistic norms are highly contextual. However, by forming these new communication systems on social media, the interlocutor of the technology itself is brought into the negotiation of linguistic conventions and norms. Further Van Dijck emphasizes in The Culture of Connectivity that when we discuss the platform itself, and the algorithms and code that govern it, we are in fact talking about something very corporate in nature. These sites maintain themselves through the sale of the meta data of users and advertising. When we speak about the technology itself as an interlocutor in the development of communication patterns, it is important to acknowledge that these sites have an ideal user in mind who uses the site in a way that is profitable to them (Van Dijck, 2013).

The recent update that allows 280 character tweets is a further example of Twitter users engaging with the technological aspects of the platform, and displaying their awareness of the effects that lines of computer code have on their methods of communication.

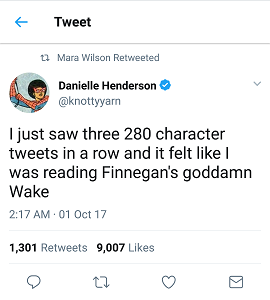

Poniewozik’s ironic tweet returns us to the contested norm of thread length – and refers to the original threading method of numbering ones’ tweets. Interestingly, it also uses the technique of the unmarked Twitter thread above - a leading sentence instead of a "complete" thought. He does not actually continue the joke through another 46 tweets, but certainly prepares the reader for such. In contrast Henderson's tweet is more clearly a complete statement, in part due to beginning the tweet with "I just saw" - it is a brief status update on something that just occurred, not a long and carefully constructed opinion piece.

Supervernaculars and Twitter threads

In discussing the phenomena of Twitter threads and the communicative conventions surrounding them, I have only scratched the surface of supervernaculars on social media. However, they are a useful case study in that they highlight several key features of social media pidgins. They are a product of both the format of the platform itself, and the social conventions and communities that have developed through the use of the platform. Indeed, when studying digitally based language communities, it is vital to understand the platforms and communication tools used not as intermediaries, but as mediators (Van Dijck 2013). Supervernaculars, or rather super-pidgins, are constructions both of their communities of language practice, but also of the algorithms and computer code that make that practice possible.

References

Blommaert, J. (2011). Supervernaculars and their Dialects . Working Papers in Urban Languages and Literacies, 1-14. Retrieved November 20, 2017, from

Gershon, I. (2010). Media Ideologies: An Introduction. Journal of Linguisitic Anthropology, 20 (2). Pp. 283-293

Lee, T. B. (2017, March 30). Why Twitter is in an uproar about the latest change to Twitter. Retrieved November 20, 2017,

Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: a critical history of social media. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weller, K., Bruns, A. Burgess, J. (2014). Twitter and Society. Peter Lang Publishing Inc.