The political message of Revival's leader Kostadin Kostadinov

Kostadin Kostadinov, known for being the leader of the far-right political party Revival (Vuzrazhdane) in Bulgaria, has taken steps towards acquiring power in the country’s political affairs. In this article, I aim to understand how this far-right leader has managed to stand out in the political crowd, and double his amount of support, winning enough votes to participate in the National Assembly. More specifically, I will evaluate his political identity by following his political message, digital media practices, and algorithmic strategy.

Who is Kostadin Kostadinov?

Revival’s leader dr. Kostadin Kostadinov has been active with his political discourse since 2010, based on the archive of his blog. However, his real quest towards governance did not set until 2014, when together with mindlike individuals he officially organized the Revival Political Party (Spasov, 2021).

According to the independent media source Dnevnik (2021), the official autobiography of Kostadinov has been modified, leaving out blank spaces from the times he was a part of other far-right parties, disliked by Bulgarians (Spasov, 2021). Some of his political values are concentrated on anti-immigration discourse, anti-EU and Nato propaganda, and strong dissatisfaction with the USA. Furthermore, Kostadinov earned his online alias - Kostia Kopeikin, based on the word kopeika (a small Russian coin), hinting at strong preferences towards Russia. Having published books and directed nationalistic movies, Kostadinov has a solid history of being explicitly pro-Bulgarian, using his strong nationalist ideas as the catalyst for his political career. Considering himself as the voice of the people, Kostadinov started to seriously gain popularity during the Covid-19 crisis. Being strictly against green passes and vaccination, Revival’s leader referred to this global epidemic as a 'plandemic', intensifying conspiracies about this topic offline and online. Through promises of the abolishment of vaccination passes and health control, he began to popularise his discourse about the revival of Bulgaria (Spasov, 2021). In the following lines, I will dive into a thorough analysis of the political discourse of Kostadinov.

Methodology

As previously mentioned my article focuses on the representation and political message of Kostadin Kostadinov by questioning his online political message and digital strategies to gather a supportive public. During this qualitative research, I have been following his social media channels primarily focusing on his Facebook, as it is the leading platform in Bulgaria based on user activity (Similarweb,2022). However, I will also analyze his Instagram content, because of the differences in personal presentation due to the digital infrastructure of the website - Instagram is much more image-oriented, which prevents the active posting of political statuses.

In order to develop a thorough analysis of Kostadinov’s political image, I will make use of multiple concepts that evaluate various, crucial aspects of political personas online:

First, I will look at the political messaging of Revival’s leader, considering that message in politics is not about the literal communication of words, but about the moral representation of the individual strategically designed around issues that are relevant to society (Lempert & Silverstein, 2016). Furthermore, Message as a term, coined by Lempert & Silverstein (2016), is concentrated more on the presentation of identity - based on the selection of issues in a politician’s agenda, meaning that one can purposely avoid certain problems and even so attribute them to an opponent, building a persona without an explicit description (Lempert & Silverstein, 2016, p.2). Additionally, political message in contemporary society is multimodal - containing all sorts of material, from clothing to language and gestures (Lempert & Silverstein, 2016, p.26), and therefore reinforced constantly to become emblematic of the figure (Lempert & Silverstein, 2016).

Secondly, through verbal representation, political figures can form their ideal identity and perform it. Thus, political discourse has a broader meaning, situating language as an activity, as a performative act (Blommaert, 2005). Here, the notion of the discursive battle for meaning will be useful to capture the discursive resources and realize temporary fixations of meaning (Maly, 2016, p. 268). Based on this, we will follow how Kostadinov reshapes and repurposes language to oppose the discourse of the left. This will act as a foundation for the concretization of his far-right narrative, opposing the normalized left.

Digital media has changed the political field. Different than mainstream media, online politicians have a platform on which they could control their own message (Maly, 2018). Of course, digital media has certain affordances that frame the possibilities of political figures, however, they also act as a resource for the active redistribution of their content (Maly, 2018). When we speak of social media, we inevitably have to speak of algorithms - therefore, information is prioritized by user activity (Maly, 2018). Digital affordances allow users to not only consume but reproduce information. In this prosumer environment, we must focus on the uptake just as much as the input of the political figure (Maly, 2021). Knowing that Kostadinov considers himself the voice of the people, embracing this populist narrative in his political presence, the notion of algorithmic populism will be useful to underline his populist discourse precisely. By looking at populism as a mediatized chronotopic communicative and discursive relation (Maly, 2018, p. 42) - the author identifies the connection between specific context and communication from various actors within the digital world as equally important to understand populism’s contemporary change. Closely connected, algorithmic activism explains how digital affordances have agency and their algorithms determine what content is being promoted actively (Maly, 2021). Knowing that in the world of information abundance, users are prosumers, it is inevitable political practices are codependent on algorithmic technology. By focusing on the user activity in the example posts of Kostadinov’s discourse, we would be able to look at the algorithmic strategy of Kostadinov and its effect on audience generation and extension.

Message politics & Discursive Battle for Meaning

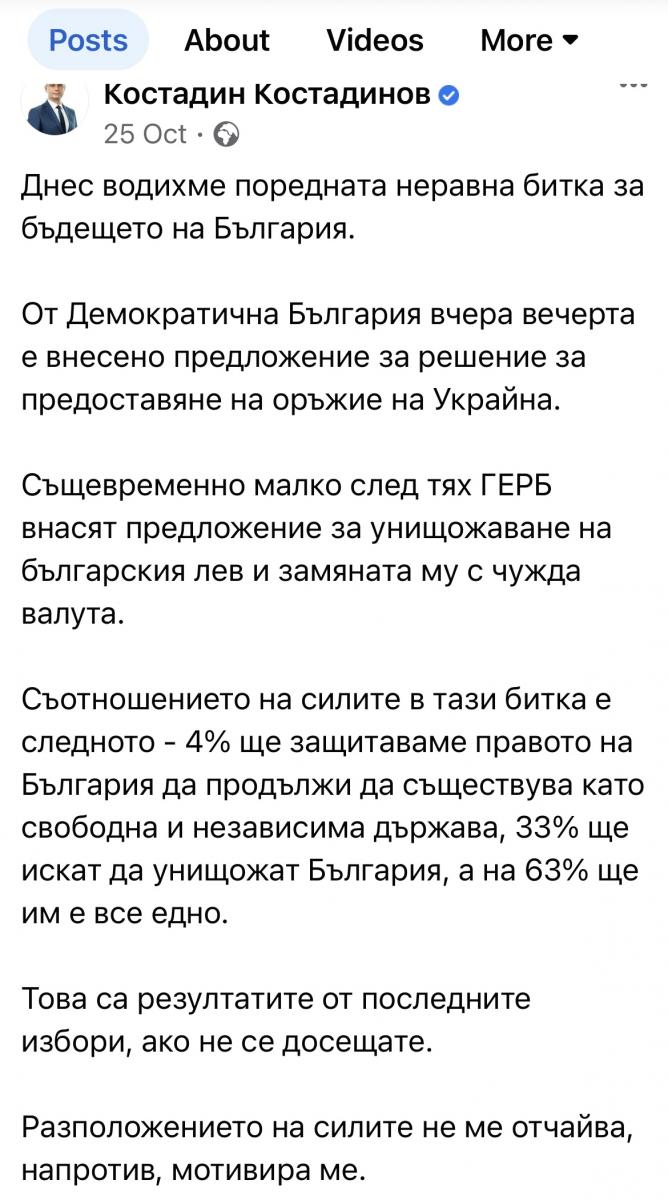

Following the screenshot of Kostadinov’s Facebook page from 25th Oct 2022:

Screenshot from the Facebook page of Kostadin Kostadinov

First, mentioning again the term Message coined by (Lempert & Silverstein, 2016), here the main focus is on the way Kostadinov uses discourse to emphasize the issues brought by the opposing parties. His Facebook status states Today we fought an unequal battle for the future of Bulgaria. Yesterday, the Democratic Bulgaria party issued a proposition for providing weapons to Ukraine. At the same time, the GERB party is proposing to destroy the Bulgarian lev and replace it with another currency (EURO). The ratio in this battle is as follows: 4 percent of us are protecting the right of Bulgaria to exist as a sovereign country, 33% want to destroy it, and the other 63 don’t care at all. These are the results from the last elections if you haven’t noticed already. This ratio doesn’t disturb me, contrary, it motivates me. (my translation)

One central point in the political campaign of Kostadinov is found in his strong disapproval of and battle against organizations such as the European Union and NATO. Moreover, he believes that by working with such organizations, Bulgaria is falling as a sovereign country, serving the interests of "others" for money. This could be understood if we analyze the abovementioned post. Based on his statement, we recognize that the other parties will cause harm to the Bulgarian population by trying to propose plans for helping Ukraine with weapons and changing the national currency to EURO, both of which Kostadinov considers as a betrayal to the national identity of the Bulgarian citizen, who he must protect. In this way, we understand that his message is about being in a battle, fighting against this type of governance that doesn’t serve his people but others.

Furthermore, focusing on the last part of his post, breaking down the meaning behind the ratio, Kostadinov uses data from prior elections to emphasize the core message of his politics - 4% of us are protecting the right of Bulgaria to exist as a sovereign country (Kostadinov, 2022). In this way, he reflects on the minority of people who have voted for his party as the only ones who care enough about their country. Thus, he frames those people as good, supporting the only true message, separating them from the others, who value the faults of the opposing parties by voting for them. Not only does he draw a line between his identity and that of other political candidates, but here we witness his discursive battle for meaning. Considering himself as part of the 4% of honest Bulgarians, he categorizes his party as the only possible aid for Bulgarian society. By doing this, he highlights that differently from the other 63%, he and his followers fight for the independence of Bulgaria. Moreover, he builds on the narrative that any other political force is harmful to the well-being of the country.

Knowing that message in politics is multimodal (Lempert & Silverstein, 2016), let’s touch on the political image of Kostadinov based on this Instagram post.

Screenshot from the Instagram profile of Kostadin Kostadinov

As a starting point, on his Instagram, Kostadinov presents a laid-back personality, based on the absence of formal clothing and the abundance of humorous posts.

As an example, in this picture from 29th May 2022, Kostadinov is captured next to a welcoming sign for the Bulgarian village Torbalazhi. As a caption, he writes The policy of Bulgarian rulers summed up in one word :) (Instagram automatic translation). Torbalazhi, if deconstructed into two words in Bulgarian, (torba & lazhi) is translated as a bag of lies. By using wordplay, Kostadinov maintains an informal social media presence that is humorous but still has a political point. Again, mentioning his discursive battle for meaning, Revival’s leader portrays the others as liars, being harmful to the Bulgarian country by working for foreign interests.

Algorithmic populism & Algorithmic activism

Following the above-mentioned analysis and the representation of Kostadinov as the savior of the Bulgarian state, we turn toward his practice of being the voice of the people. Touching again on algorithmic populism, it is important to observe how his discursive battle realizes his populist identity in the digital world.

Understanding populism as a chronotopic communicative relation highlights that populism is the result of a complex interplay (Maly, 2018, p.44) between input and uptake from social media users. Therefore, first, we must look at how Kostadinov frames himself in a populist narrative within a specific context, generating discourse against the established political elite to protect the freedom of society.

In this post, Kostadinov writes:

Differently from the majority in the present National Assembly, we - the Bulgarians, have only one Homeland!

We are ready to give our all in the name of its future!

It is high time Bulgaria is independent.

It is high time for Revival! (my translation)

Screenshot of Facebook post of Kostadin Kostadinov

Based on the first sentence in his Facebook post, Kostadinov openly differentiates himself and his party’s agenda from other political figures in the National Assembly. Moreover, he labels them as individuals who are serving someone other than their own homeland, again contextualizing Bulgarian politicians as being dependent on third-party organizations like the EU or NATO. Further, Kostadinov unites himself and his followers under the pronoun “we”, focusing on their nationality and union as individuals who love their country. This could be additionally justified, if we consider that he wrote Homeland with the capital letter “H”, highlighting its importance. By framing his discourse in such a way, he maintains his nationalist, voice-of-nation discourse, asserting his populist identity.

Furthermore, focusing on his last remark in the post: It's high time for revival, drawing from the work of Roger Griffin (1996) on palingenetic (ultra)nationalism, we can see how the idea of national rebirth is maintained. As Griffin (1996) coined it, palingenetic (ultra)nationalism is based on the myth of palingenesis or rebirth after decay in politics, when political figures persuade the nation to support their policy by accommodating the idea of social revival. Additionally, through this charismatic representation of populist nationalism, society is strategically given a sense of transformation and transition - this is especially important for people that have been disappointed by previous governance. In a way, the myth of palingenesis is used strategically to shift people's perspective, disassociating from the practice of controlling and focusing on choice and emotion. While Griffin (1996) created this concept based on generic fascism, the contemporary use of this practice could be picked up in far-right policing. Such discourse on social media could be expressed through the remarks of Kostadinov, whose foremost claim is to reinvent political practices in Bulgaria, to revive the country's greatness.

Similarly, in this post with the following text:

“I vow that I WON’T step back even a centimeter in the battle for the national interest of our Homeland. “

Screenshot of Facebook post of Kostadin Kostadinov

Again, we witness the strong nationalist discourse - his oath to fight for his land, the union between him and his followers (our homeland) in the battle against the ‘others’ for their Homeland (again emphasis on the capitalized 'H').

In algorithmic populism, user uptake is just as important as the analysis of the political figure and digital affordances due to their endless interaction. Knowing that digital algorithms are moderators who not only support but transform political practices online, it is necessary to touch on the connection between actors and algorithmic activism. Focusing on the activity in the presented posts above, Kostadinov’s discourse has been picked up by a significant number of users.

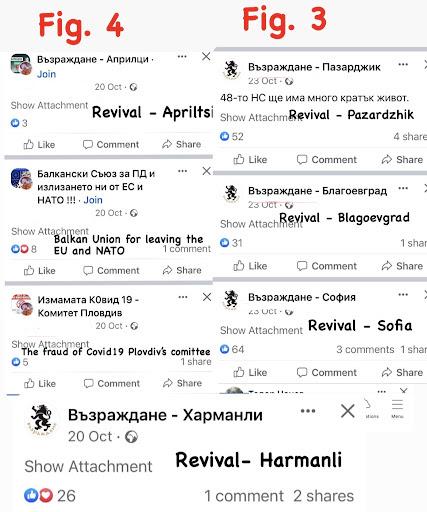

Concentrating on the shares as metrics for popularity, it is obvious that they are relatively high in numbers. Diving even deeper, both posts have been reshared by the pages of local committees of Revival or other groups presenting similar views against the Covid-19 pandemic, EU or NATO.

Screenshots of the resharing of posts

In figure 5, highlighted in red, a single user distributes one post within three groups, formulating a new arena for political discourse and feeding the algorithm with data, allowing others to forward the posts as well. Although the reshared posts have not gotten a lot of attention, the groups in which they have been shared have relatively big audiences. An example of that is the group named The fraud of Covid-19 Plovdiv’s committee which has 4 thousand members and is an open-access group, allowing non-members to look at the content in it.

The same could be awarded to the local town groups in support of Kostadinov’s party - Revival - Sofia having over 11 thousand followers and Revival - Pazardzhik with 2.2 thousand. It is this way of resharing that spreads his populist messaging to people who are committed to the same beliefs, therefore actively triggering the algorithm to help with the dissemination of ideas which then organizes mass media coverage.

As described by a mainstream media source Kapital Insights (2022), Kostadinov uses very well the social media and jumps on the populist anti-establishment bandwagons (Dimitrov, 2022), once again justifying his active use of algorithmic practices intertwined with populist ideas. By being acknowledged by both users and mainstream media actors as populist, his discursive and interactive project is seemingly being picked up by potential voters.

Following an offline metric of popularity, the analysis of Kostadinov’s rise in votes from the last two years builds on the abovementioned point. In 2021, Kostadinov’s party went just above the 4% line, being able to participate in the Assembly with 13 politicians. However, in October 2022, after another round of elections, the party doubled its support, winning little above 10 % of the voters and having 27 seats in the Assembly.

Many different factors have contributed to this success in the political development of Kostadinov, from organizing his political message around the social issues in the country brought by the opposing parties to the spread of populist ideas online through the proper use of digital affordances. While his political future remains unknown, it is undoubtful that he has a growing audience.

Wrapping up

Digital media has altered the way politics are represented online. From building a stronger message and identity to capturing the attention of others through discourse. Kostadin Kostadinov has been in combat with fellow politicians for the trust of Bulgarian society. Furthermore, he has made this battle his central remark for persuasion of voters to support him. By forming his discursive battle around the faults of the status quo, Revival’s leader built a political identity that is grounded on the rebirth of values, strong nationalism, and populism. Furthermore, he has been able to realize his identity actively, pronouncing himself as the voice of the nation that is tired of being dependent, as the people who need to be revived, formulating an audience of like-minded individuals on social media, increasing his popularity through algorithmic strategy, collecting votes that give power.

References

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Dimitrov, M. (2022, June 20). The New Bulgarian Radical Party - how worried should we be about Vuzrazhdane? Kapital Insights.

Griffin, R. (1996). Staging the Nation’s Rebirth: The Politics and Aesthetics of Performance in the Context of Fascist Studies. Fascism and theater: comparative studies on the aesthetics and politics of performance in Europe.

Lempert, M., & Silverstein, M. (2016). Introduction - “Message” Is the Medium. In Creature of Politics (pp. 1-57). Indiana University Press.

Maly, I. (2016). ‘Scientific’ nationalism - N-VA and the discursive battle for the Flemish nation. Nations and Nationalism, 22(2), 266-286.

Maly, I. (2018). Populism as a Mediatized Communicative Relation: The Birth of Algorithmic Populism. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies.

Maly, I. (2018, October 10). Algorithmic populism and algorithmic activism | diggit magazine.

Maly, I. (2021). Ideology and algorithms. Ideology Theory Practice.

Spasov, S. (2021, November 19). "In the name of the nation we are sentenced to death!"- where did Kostadin Kostadinov come from. Dnevnik.bg.

Top Social Networks And Online Communities Websites Ranking in Bulgaria in October 2022. (2022, October). Similarweb.