Longing for the present: Nostalgia in contemporary faux-vintage photography

Recently, vintage aesthetics have re-emerged among teenagers and young adults who are fascinated by the early lives of their parents and older relatives. In the world of information overload, where little seems to be interesting enough to capture our attention, the past has been recycled into new microtrends inspired by retro aesthetics. However, this new obsession with the old has transformed how we create and perceive nostalgic feelings. These days we experience the acceleration of nostalgia (Cochrane, 2022), taking away the original melancholic longing, and turning it into a trivial urge for authenticity. We do this through fashion by circling trends in clothing from the 80s and 90s, through music, streaming fan favorites from the year 2000, and through the entertainment industry, remaking movies and TV shows from earlier times. The banality of nostalgia is especially prominent in faux-vintage photography, where users online are remembering what appears to be something they haven’t experienced in the first place.

In this paper, I will evaluate the trend of faux-vintage photography, questioning the intentions behind the practices of users indulging in the use of vintage editing tools, filters, and effects. By building a case study on Booth by Bryant, a photobooth trend set off by a famous photographer, which was later the inspiration for a TikTok trend with the same name, I will present the recreation and readaptation of analog photography into the world of digital virality. Furthermore, I will focus on the change of perception when it comes to nostalgia, arguing that it is self-induced by the creator of an image in the digital world, turning it into an emotional and reflective idea that has little to do with general perceptions of destructive longing and grief.

The History of faux-vintage Photography

The use of retro filters is not an entirely new practice but a phenomenon that has been building up since the emergence of the mobile phone equipped with a camera. Because of the availability of this portable device to take pictures instantly, photography became a practice for all and a reason to capture every aspect of our lives (Chopra-Gant, 2016, p.122). Soon enough, photo-editing digital applications popularized amateur photography further, allowing users to alter the visual properties of any picture, giving it a vintage flair. This practice was conceptualized under the term faux-vintage photography, coined by Nathan Jurgenson (2011). One of the biggest producers of such content was Instagram (Chopra-Gant, 2016, p. 125), which back in 2010 was just a start-up networking social media platform that provided a space for sharing images and editing them with retro filters having the signature square format, replicating the shape of a Polaroid picture.

Screenshot of camera menu on Dazz Cam

As digital media progressed, more apps have been introduced, giving the user a chance to choose a vintage camera from the past and take a picture with it or use a template to achieve a film-like aesthetic. Dazz Cam (2021) and Tezza (2018) are at the forefront of contemporary faux-vintage photography, coming up with new and improved filters and effects that can give off an emotional and nostalgic appearance to any image. Most importantly, when exploring the synthesis between the analog and the digital with these apps, we witness the modification of the past. We are simply unwilling to let go of it and are ready to adjust it to the post-digital era.

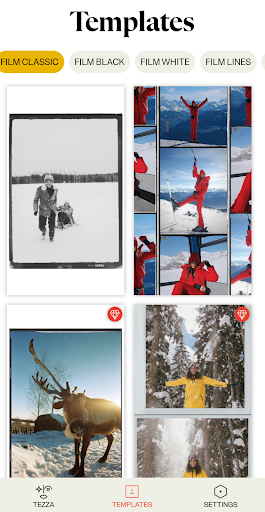

Screenshot of the menu of Tezza App

Method and Theory

As previously mentioned, this paper will focus on the contemporary use of vintage filters specifically exploring the reasons behind it starting with the essay of Nathan Jurgenson (2011) as a guide. In his analysis called The Faux-Vintage Photo (2011), Jurgenson raises the question about the reasons behind the phenomenon of faux-vintage photography. More specifically, he tests if quality and creativity could be interpreted as aspects persuading users to edit their photos with vintage filters. While Jurgenson does not entirely erase this possibility, he dives deeper into the meaning behind retro filters arguing that they are the point of departure for the creation of nostalgia for the present (Jurgenson, 2011). Furthermore, his argument suggests that through vintage photo-editing, users give importance and substantiality to their images by incorporating the feeling of nostalgia (Jurgenson, 2011).

Through vintage photo-editing, users give importance and substantiality to their images by incorporating the feeling of nostalgia (Jurgenson, 2011)

However, in the second part of the analysis, he departs from the original definition of nostalgia. Originally understood as "a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for a return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition" (Webster, n.d.), nostalgia was defined by the scholar Johannes Hofer (1668) as a disease, severe homesickness which could lead to health problems (Nostalgia, n.d.). Differently, Jurgenson (2011) considers nostalgia as a longing not only for a physical place but for the past, a period of time, or an era. Therefore, he argues that the visual properties of retro-edited pictures could invoke memories leading to nostalgia. Moreover, these properties have the power to materialize digital content through the use of editing styles such as grain, exposure, and formatting, similar to how analog cameras deliver real-life images (Jurgenson, 2011). In this way, Jurgenson (2011) argues that vintage effects could also make an image seem more authentic and real. This form of fake authenticity is considered a self-aware simulation in which users willingly edit a photo from the present to match the past. Importantly, Appadurai (1996) refers to this phenomenon as imagined nostalgia or armchair nostalgia defining it as the representation of "things that never were" (Appadurai, 1996, p. 77). Based on this, we can find the connection between contemporary editing approaches that invoke "nostalgia without memory" (Appadurai, 1996, p. 30).

Connecting this to Jurgenson’s (2011) main argument about nostalgia in the present, we witness how photos graphically age our captured moments to show the here and now as a past for which we are already nostalgic (Caoduro, 2014, p.73). Jurgenson (2011) considers what people post as a documentary, in which those who are severely influenced by social media and the possibility to have a digital audience, start to perceive everything as a self-documentative possibility. Thus, a person collapses the present and the past, living simultaneously with the idea of something happening right now which could be documented right after, and if edited with a retro filter, becoming nostalgic.

By perceiving nostalgia as a self-induced practice (Bartholeyns, 2014, p.55) through faux-vintage photography, in this paper, we would be able to analyze the case of Booth by Bryant and the TikTok trend inspired by it, to understand how current obsession with vintage aesthetics in photography has been influenced by digital affordances, detaching netizens from the authentic perception of nostalgia, blurring the lines between old and new, pursuing users to conceptualize their present as an instant past.

BOOTH by Bryant is trending

Bryant Eslava is a famous photographer based in Los Angeles, mostly known for his collaborative photo sessions with influencers, digital content creators, and celebrities. His recent project named BOOTH by Bryant was inspired by an MTV Photobooth book from the early 2000s, where celebrities took pictures in the booth, whenever they were working with MTV. Bryant’s main intention for this creative project was to purchase a photobooth where his friends could have fun and memorable moments, however, this artistic initiative has become a fixture of Instagram and TikTok feeds (Sangster, n.d.).

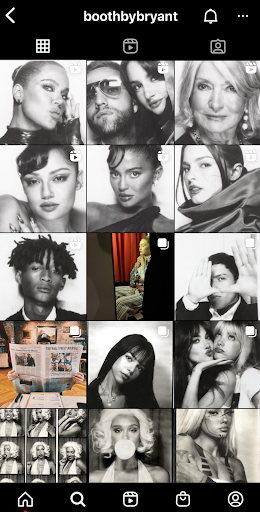

Screenshot of Booth by Bryant's Instagram page

BOOTH by Bryant represents the authentic old-fashioned way of materializing a moment in time. Being influenced by the ongoing craze for nostalgia among young people on social media, Bryant has unintentionally intensified the desire of users to capture intimate, vintage portraits of themselves. Using real analog technology to make art, Bryant has managed to bring back to reality the use of authentic materials of photography as opposed to artificial filters and effects. Yet in a world where anything can be digitally recreated, Bryant’s booth was instantly copied, creating an entire TikTok/Instagram microtrend called the photobooth trend.

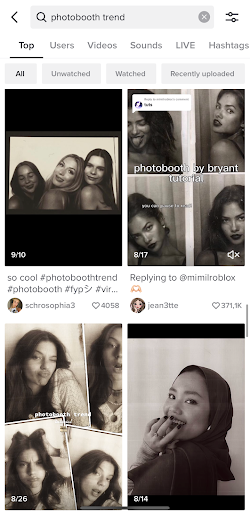

At first, there were a few who figured out what photo-editing application to use in order to achieve this grainy and dark aesthetic. Soon enough users on TikTok made tutorials explaining what is the app that could virtually take you to Bryant’s photobooth. As a result, by typing the photobooth trend on TikTok, we can infinitely scroll through videos that have the signature grainy, black-and-white aesthetic of BOOTH by Bryant.

Screenshot of search page for photobooth trend on Tik Tok

Going back to Jurgenson’s essay (2011), BOOTH by Bryant encapsulates the theory of nostalgia for the present. While Bryant’s original idea is structured around an authentic analog machine and the printing of real-life pictures, the inspired digital trend illustrates the urge for authenticity and uniqueness that retro photographs seem to entail. More importantly, the users jumping on this trend are self-inducing nostalgic conditions by purposely documenting altered photos that happened a moment ago to match with the ones of Bryant. Similarly, influencers and celebrities who have taken a picture in the real booth are also presently nostalgic. By posting their vintage portraits taken in the booth on social media, they are documenting moments that have happened in the recent past, although authentically taken, still representing an older era that they have not been a part of through visual properties. From this, we can understand that their reference to another bygone time is not grounded in negative feelings of loss, but rather in an emotional connection to the aesthetics of the past. Drawing back on the armchair nostalgia of Appadurai (1996), what he considered the practice of creating "experiences of loss that never took place" (Appadurai, 1996, p. 77 ), in this context, has transformed into making images that were never in the past. The use of vintage filters is a tool for the subconscious materialization of a digital image, making it feel like an analog outcome online, giving the viewer a feeling of nostalgia.

Their reference to another bygone time is not grounded in negative feelings of loss, but rather in an emotional connection to the aesthetics of the past

In this way, we can see how this vintage photobooth trend, similar to how Instagram was perceived as a tool for realizing nostalgia (Jurgenson, 2011), can blur the lines between old and new. By exaggerating the visual properties of photographs, making them look vintage, coming from another era, users are embracing the contemporary idea of nostalgia and not the real concept.

What is the future of nostalgia for the vintage?

Interestingly, more than 10 years ago, Nathan Jurgenson (2011) concluded his essay with the prediction that faux-vintage photography will be a passing fad due to the high use of retro filters to achieve authenticity, resulting in the paradox of similarity between users online. While they were quite irrelevant before becoming popular again in 2022, what we have witnessed is the rapid circulation of materials in the digital world which inspires the return of not only vintage but all kinds of passed-period products and ideas. Randall Jarrell (1960) unites all types of mass media as the medium in A Sad Heart at the Supermarket, where he reflects on the swiftly growing consumerism and dependence on the entertainment/advertisement industry as well as the loss of artistic and cultural value. Moreover, he indicates what is very much relevant for present-day society - the medium is the center of our being, showing what is trending and likable, putting virality before quality.

The consequences of the technological turn in society could be explored based on the contemporary understanding of nostalgia in the present, where longing is romanticized and reduced to aesthetic value, different from its original deep psychological meaning. Moreover, back in 1960, Jarrell picked up on the necessity of constant production and consumption which is foundational for the speed at which we create and popularize trends.

This leads to a culture that is periodical (Jarrell, 1960, p. 363), with reducing value, intensifying the soon-disappearing character of trends.

Similarly, Lauren Cochrane (2022) writing for The Face, believes that this constant obsession with nostalgia is accelerating the recycling of trends, driving them into a revival spiral, where netizens are shifting back and forth between different eras at once. Thus, we understand that although Jurgenson thought of faux-photography as something momentary, it is not outrageous to think that all of this could come back somewhere in the future.

While the use of retro filters is not a new phenomenon, but a growing one, thanks to the circulation of trends on TikTok and Instagram, from what we have explored so far, as a concept, it showcases how it is possible to transform aspects of the analogous past into the digital future while maintaining a sense of authenticity. Furthermore, faux-vintage photography realizes young society’s interest in vintage aesthetics and culture, simultaneously raising questions about the meaning of nostalgia in contemporary times.

Based on this, the problematic character of self-induced nostalgia in images mentioned at the beginning becomes apparent since creators of content channel unrealistic longing that is materialized through filtering, representing a unique emotional value that is in contrast with the destructive origin in the meaning of nostalgia because it has no general connection to the past as it is created in the present. While it is uncertain whether faux-vintage photography will remain popular as time progresses, for now, vintage/retro aesthetics are constantly being reimagined in films, music, and fashion.

References

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: cultural dimensions of globalization (Ser. Public worlds, v. 1). University of Minnesota Press

Bartholeyns, G. (2014). The Instant Past: Nostalgia and Digital Retro Photography. In Media and Nostalgia - Yearning for the past, present and future (pp. 51-69). Palgrave Macmillan memory studies.

Caoduro, E. (2014). Photo Filter Apps: Understanding Analogue Nostalgia in the New Media Ecology. Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, 7(2), 68-82.

Chopra-Gant, M. (2016). Pictures or It Didn’t Happen: Photo-nostalgia, iPhoneography and the Representation of Everyday Life. Photography & Culture, 9(2), 121-133. 10.1080/17514517.2016.1203632

Cochrane, L. (2022, February 23). Our obsession with nostalgia is driving a trend revival spiral. The Face.

Jarrell, R. (1960). A Sad Heart at the Supermarket. Mass Culture and Mass Media, 89(2), 359-372.

Jurgenson, N. (2011, May 14). The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) - Cyborgology. The Society Pages.

Nostalgia. (n.d.). Online Etymology Dictionary.

Sangster, E. (n.d.). Everything to know about the ethereal Booth by Bryant photographs à la Jaden Smith and the Kar-Jenners. Harper's Bazaar.

Webster, M. (n.d.). Nostalgia. Merriam-Webster.