Schlingensief's Big Brother of Xenophobia: Antagonism in participatory art

The Austrian elections of 2000 marked a significant political shift to the right as the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) under Wolfgang Schüssl formed a coalition with Jörg Haider’s Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ). The FPÖ, a far-right party with publicly known ties to the extreme-right scene used xenophobic speeches and posters for their election campaign. The inauguration of the government on the 4th of February led to national and international outrage since it was the first time after World War II that a far-right party made it into the government of a European country. Opposition against the newly formed government grew quickly and new elections were demanded during weekly demonstrations. Furthermore, Austria experienced a reduction in diplomatic ties from 14 EU member states and both Israel and the USA withdrew their ambassadors (Moldenhauer, 2015). The political situation was highly tense as this new government alliance confronted Austrian citizens with a principal question: what do these elections reveal about our national identity; is Austria a xenophobic country?

This article investigates the antagonism and provocation of Christoph Schlingensief’s multimedia installation "Bitte liebt Österreich". The aim is to answer the research question: how does Schlingensief's participatory art installation "Bitte liebt Österreich" provoke public engagement with xenophobia and far-right politics in Austria? The theoretical ground of participatory art will be outlined through the scholarly work of Claire Bishop (2006) and Walter Benjamin (2006). Following this, the participation of the public in the installation will be investigated. Furthermore, the article sheds light on "Bitte liebt Österreich's" artistic ends and how these are achieved. Finally, the article addresses if the project was real or staged

"Bitte liebt Österreich"

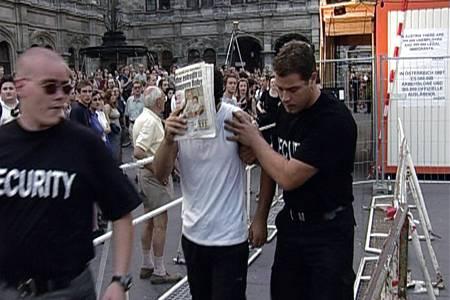

In June 2000, following the formation of the right-wing coalition, German artist and agent provocateur Christoph Schlingensief poured oil on the political fire that was burning in Austria. As part of the yearly cultural festival "Wiener Festwochen" he created a participatory multi-media installation called “Bitte liebt Österreich“ (Please love Austria) in the touristic center of Vienna. Self-described as "cultural terror" (Poet, 2002), the artistic project resorts to drastic measures. In a critical thought-provoking response to the FPÖ’s far-right agenda "Ausländer Raus" (Foreigners Out), the artist devised a six-day long multimedia installation situated on the Herbert-von-Karajan-Platz by the Opera which was centered around the establishment of a simulated mock deportation camp. The deportation container was covered with the FPÖ’s flag, xenophobic election posters and banners of the Kronen Zeitung, the most-read Austrian boulevard newspaper characterized by right-wing populism, emotionalization, and opinion-making. On top of the container, a big banner showcased the Nazi rhetoric slogan “Äusländer Raus”.

Figure 1 The deportation container on day 1

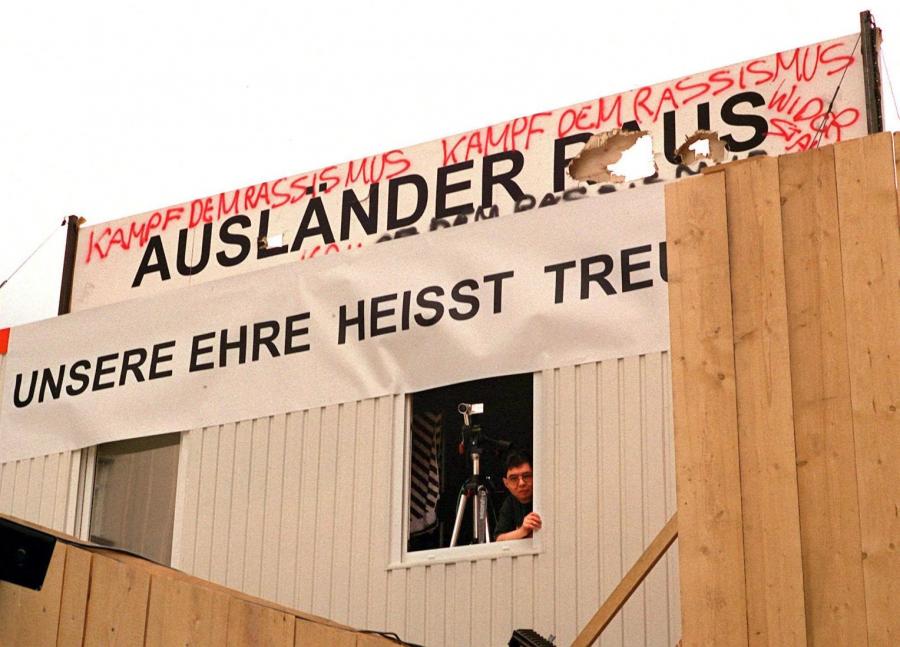

Resembling the reality TV format of Big Brother, 12 asylum seekers voluntarily entered the container to be filmed 24/7 and the recording was live-streamed on the website webfreetv.com. A cruel online voting system on the project's website www.auslaenderraus.at invited the voyeurs to vote out one "foreigner" every day; not only out of the container but also out of the country. Those eliminated would be deported from Austria until one "winner" remained. The winner would be awarded a "prize" of 35.000 Schilling (Austria's currency until 2002) and would be granted the chance to obtain Austrian citizenship if one of the viewers would offer to marry him (Austria's currency until 2002). The winner of the prize money and project was Ranil Shunta, a 29-year-old informatics student from Sri Lanka (Poet, 2002). If he ever married an Austrian citizen remains unknown. The participatory art project is documented by director Paul Poet under the name Ausländer Raus: Schlingensiefs container (2002).

Figure 2 An asylum seeker leaving the container after being voted out

Theoretical framework

The following theories will be used to analyze the participatory art project "Bitte liebt Österreich" and will therefore be elaborated on.

The British scholar Claire Bishop (2006) outlines the nature of participatory art in her text "Viewers as Producers" and draws on the work of Walter Benjamin. According to Bishop (2006), participatory art draws to the social dimensions of art; they are “socially-oriented projects” (Bishop, 2006). The art form is not merely interactive or immersive but hinges upon the active and physical participation of the audience. At the core, participatory art focuses on “collaboration” and “the collective dimension of social experience” (Bishop, 2006). It blurs the boundaries between artist and spectator, “professional and amateur, production and reception” (Bishop, 2006).

There are two distinct lineages in participatory art. Firstly, the "authored tradition" aims to provoke participants in a disruptive and interventionist manner, drawing inspiration from movements like Dada. Second, the "de-authored tradition" embraces collective creativity and emphasizes the construction of artworks through collaborative efforts, influenced by movements such as Constructivism. The origins of participatory art can be traced back to the 1910s and 1920s when avant-garde movements like Futurism and Dadaism pioneered artistic "manifestations" that actively involved the public. Simultaneously, in the Soviet Union, large-scale spectacles such as "The Storming of the Winter Palace" (1920) took place; a grand reenactment of the events surrounding the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (Bishop, 2006).

The Austrian citizens co-created "Bitte Liebt Österreich"

Walter Benjamin wrote "The Author as Producer" in 1934 and was inspired by the Soviet spectacles and the German dramatist Berthold Brecht. Brecht was a pioneer of his time as his form of theater went beyond traditional paradigms by urging the spectator to adopt a stance in relation to the depicted action. In comparison to today's participatory art, the audience's participation in Brechtian theater is still rather passive. But it functioned as a precursor for modern participatory art. Benjamin argued that art should enable the involvement of the audience in the production process, turning “consumers into producers” and “spectators into collaborators” (Benjamin, 1934).

Participation in Schlingensief's Big Brother of Xenophobia

The multimedia installation "Bitte liebt Österreich" transcends the boundaries between “artist and spectator” as well as “production and reception” (Bishop, 2006) by inviting and provoking the public to actively participate in the installation. The nature of the participatory art project invites various contributions to the process, meaning, impact and final outcome of the project.

First, Schlingensief incites the public to take part in the online voting system of the installation: “Vote out your favorite asylum seeker you hate the most” (Poet, 2002). The recorded numbers speak for themselve; within the six days of the project 813.000 people participated in voting out and deporting the asylum seekers they were watching on the live stream (Bitter, 2021). In this way, viewers were not merely interacting with the artwork but were actively participating in it. The participatory nature of the voting system transformed the public’s role from passive “spectators” and “consumers” into active “collaborators” and “producers” (Benjamin, 1934). Their involvement in the installation made a significant impact on the outcome of the project: their engagement decided who would remain in the project and also if the installation would work in the first place. If no one would have voted, the outcome and social impact of "Bitte liebt Österreich" would have been significantly different. Hence, the Austrian citizens co-created the installation.

Second, Schlingensief encourages tourists to take pictures of the banner and distribute them around the world: “Take pictures, show them in your home country, show the future of Europe” (Poet, 2002). He also invites the public to “enter the peepshow” (Poet, 2002) by looking into the container and interacting with the asylum seekers, again transforming the public into “collaborators” and “producers” (Benjamin, 1934).

Schlingensief: “We have created a product that has taken on a life of its own, much like a virus in the body”

Third, the illustration is antagonistic, provocative and confrontational to the bone triggering the participation of the public: the inhumane concept of the deportation container (deport the asylum seeker you hate the most), Schlingensief’s blunt reproduction of the far-right populist rhetoric of the FPÖ in an ‘in your face’ manner, the xenophobic election campaign posters and the huge sign displaying the Nazi slogan "Foreigners Out" right by Vienna’s prestigious opera house. All of these elements force those present to leave their role of spectators and become active collaborators and producers, thereby shaping the public discourse around the project.

The public outrage was immense. Hundreds of people from all sides of the political spectrum gathered at the installation everyday and participated in heated political, social, and ethical discussions. Public hostilities, physical fights, and demonstrations - organized by both the left and the right - were no exception. On top of that, there was an arson attack on the container and death threats were uttered toward Schlingensief. On the fifth day of the installation, left-winged protestors climbed the container and sprayed “resistance” and "fight against racism" on the "Foreigners Out" banner (see Figure 3) and destroyed the FPÖ flags.

Figure 3 Demonstrants spraying resistance graffiti on the Nazi slogan banner

"Bitte liebt Österreich" effectively reveals the true nature of Austria's political landscape

They also violently entered the container to rescue the asylum seekers that were, in their eyes, victims of inhumane treatment. This eventually caused them to be evacuated overnight. The next day, the installation continued as before. This public hysteria is part of the installation and shows its social dimensions. The active participation of the public highlights its ability to co-construct the project. In a documentary about the project Schlingensief explains: “We have created a product that has taken on a life of its own, much like a virus in the body” (Poet, 2002). Another commentator said: “It’s like throwing a stone into the water and watching the waves” (Poet, 2002). As such, even though "Bitte liebt Österreich" hinges upon Schlingensief, its impact and final outcome rely on the active participation of its audience.

The artistic ends of the installation

"Bitte liebt Österreich" is clearly a confronting and provocative response to the government formation with an extreme-right party. Schliengensief argues “It was not an amnesty international project” (Poet, 2002). The installation holds up a confronting mirror to Austria’s society and political landscape in a thought-provoking manner. The provocative and antagonistic nature of the project forces individuals to confront uncomfortable truths, reflect on the political climate in Austria, and participate in public discourse around it. Xenophobia is publicly mirrored by showing the discriminatory campaign materials and the FPÖ flag, and by including the name of the Kronen Zeitung. All of these elements function as a critique of Austria’s political reality and illustrates 21st-century fascism. Schlingensief incites the public with its own reality: “This is the truth, this is the FPÖ, this is the Kronen newspaper, this is Austria” (Poet, 2002). The project has demonstrated that pure quotation and mirroring alone are sufficient for criticism when deployed at the right time and place. By directly representing what is being criticized, "Bitte liebt Österreich" effectively reveals the true nature of Austria's political landscape without requiring additional commentary.

On top of that, the installation’s voting system - through which participants are able to decide over the life of powerless asylum seekers - aggressively draws attention to the “juridical death” of stateless refugees (Center, 2021). Apart from highlighting their vulnerable position, the project also gives a name and a face to those individuals - often generically referred to as "foreigners"- who are dehumanized by the FPÖ and Kronen Zeitung,

Finally, the mock deportation participatory art project aligns with Bishop’s (2006) "authored tradition" rather than the "de-authored" lineage due to its clearly disruptive nature and interventionist aim.

Real or staged?

The agent provocateur Schlingensief actively played with the public confusion of whether those in the container were real asylum seekers who would actually be deported from Austria. He left the Austrian public in the dark about the truth to instrumentalize the confusion, thereby inciting participation and achieving the artistic ends of the art project. In a lecture on "Bitte liebt Österreich" at Utrecht University in 2012, contributing dramaturge Matthias Lilienthal clarified that the people who stayed in the container were not actors but real asylum seekers who were recruited at the migrant residence in Gratz and were paid a fee as compensation. Lilienthal explained that the individuals were "of course not" deported from the country when leaving the container but returned to the migrant residence in Gratz (West, 2023). This shows that the project was a simulation to mock Austria's asylum policies and an attempt tp aggressively draw attention to its cruel realities. Whereas the experiences in the container must have undoubtedly had real-life consequences for the asylum seekers, the voting system of the project did not decide on the future of their stay in Austria.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Schlingensief's participatory art installation ‘Bitte liebt Österreich’ successfully provoked public engagement with xenophobia and far-right politics in Austria through its antagonistic, confrontational, and provocative approach triggering public discussion. Drawing on the theoretical framework of participatory art outlined by Claire Bishop and Walter Benjamin, the installation’s participatory nature blurs the boundaries between artist and spectator, transforming passive spectators into active collaborators and producers of the installation. The public participated by voting out asylum seekers on the website, having heated debates, demonstrating, spraying graffiti of resistance on the container, and even entering the container to “rescue” the asylum seekers. Thus, the project transformed the passive role of spectators and provoked them to confront uncomfortable truths and to actively participate in shaping the outcome and impact of the project.

"Bitte liebt Österreich" shed light on the issue of xenophobia and far-right politics in Austria. By actively involving the audience and confronting them with the uncomfortable realities of 21st-century fascism, the installation succeeded in provoking reflection and action and served as a powerful artistic critique of the prevailing political discourse.

References:

Benjamin, W. (1934). The author as producer. In E. L. Fackenheim (Ed.), Illuminations: Essays and reflections (pp. 220-238). Harcourt, Brace & World.

Bishop, C. (2006). Viewers as Producers. In Participation (Vol. 1, pp. 43-63). Whitechapel Ventures Ltd.

Bitter, A. (2021, April 27). Ausländer raus! Schlingensiefs container. Filmgalerie 451. https://www.filmgalerie451.de/de/filme/auslaender-raus-schlingensiefs-co...

Center, H. A. (2021, December 7). Outside the Pale of the Law: Rightlessness on Reality TV in Christoph Schlingensief’s Bitte Liebt Österreich. Medium. https://medium.com/amor-mundi/outside-the-pale-of-the-law-rightlessness-...

Moldenhauer, B. (2015, December 28). Christoph Schlingensief: Der asylbewerber-container in Wien. DER SPIEGEL. https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/christoph-schlingensief-der-asylbewerb...

Poet, P. (Director). (2002). Ausländer raus - Schlingensiefs Container [Film].Film Fonds Wien.

West, F. (2023, June 27). Matthias Lilienthal - Ausländer Raus: Bitte liebt österreich, or Christoph Schlingensief’s big brother.. - lecture - 08/03/201. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/80473909