Pinky Glove: A feminist analysis of the menstrual status quo and digital menstrual activism

This essay provides a feminist analysis of the subject of menstruation and its socio-cultural implications in German society and media. It will examine a digital menstruation blood discourse from a feminist lens zooming in on a case study of the pinky glove scandal and menstrual activism on digital media. Key theoretical concepts used for the analysis are stereotypes (Ott & Mack, 2014), stigmata (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2020), and new blood-third wave feminism (Bobel, 2010).

The data gathered for this research has been collected between the 5th of November and the 3rd of December 2022, from the social media platforms Instagram and Twitter and online news platforms. Findings reveal that stigmata and stereotypes have led to a negative societal construction of menstruation. A menstrual taboo is to be observed, as well as the fact that menstruation is associated with pejorative attributes such as shame and impurity. A strong backlash against this emerged with menstrual activism. Online activists are challenging the menstrual status quo, advocating to break the taboos and stigma surrounding menstruation and promoting menstrual health and rights utilizing the affordances of digital media.

The stigmatization of menstruation

Menstruation is often not viewed as a neutral phenomenon. Instead, it has been socially and culturally constructed and stigmatized. This analysis focuses on the belief of menstruation as an abomination (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2020). Menstruation is associated with negative stereotypes, for instance, the belief that those who menstruate are ‘unclean’. This goes hand in hand with the fact that menstrual blood is broadly more stigmatized as ‘repulsive’ and ‘unhygienic’ than other bodily fluids such as semen (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2020). Furthermore, menstruation is often considered a private matter that should not be discussed openly. Thus, stigmata are indirectly perpetuated through silence (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2020). The fact that periods are not neutral but a “stigmatized condition” (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2020) can be seen in a survey conducted by the "feminine" hygiene company Thinx that revealed that 58% of female participants feel ashamed when they menstruate (Petter, 2018). On top of that, 42% of questioned participants had experienced period shaming (Petter, 2018). This shows how largely menstruators are affected by negative social conceptions of periods. Non-menstruators (aka boys/men) are also affected by stigmata in the way they understand periods, as research by Plan International underlines: more than 1 in 3 of the boys interviewed think that periods should be kept a secret (Plan International, 2022). This highlights the taboos around periods that are rooted in our society and shape the way we see and treat menstruation.

This analysis will investigate the menstrual status quo and its representation in German media, and look at menstrual activists drawing to academic works by Ott and Mack (2014) and Bobel (2010). Firstly, the essay conducts a case study of the Pinky Glove scandal from 2021 through a feminist lens examining its sociocultural implications. Secondly, the backlashing menstrual activism on social media under the viral #PinkyGate will be investigated. The article aims to answer the question of what the sociocultural implications of socially constructed stigma, stereotypes, and taboos surrounding menstruation in contemporary German society and media are. How does digital menstrual activism combat the stigmatized menstrual status quo?

Feminism and feminist (menstrual) activism

Ott and Mack (2014) define the aim of feminist analysis as the deconstruction of popular media texts to shed light on false binaries and the patriarchal systems that they support. Moreover, feminist analysis untangles stereotypes in society and in media representation and their social, cultural, as well as political implications (Matt & Ott, 2014). The purpose of this feminist analysis is to delve into the topic of a digital menstruation blood discourse with a focus on feminist menstrual activism (#PinkyGate) challenging normative stigmatization and stereotyping of periods as represented in media (Pinky Glove) that mirror and reinforce the negative social construction of periods. This essay understands feminism as a political project that examines various ways in which men and women are socially disempowered and empowered. Additionally, feminism deconstructs sexist oppression that is rooted in everyday experiences and norms (Ott & Mack, 2014).

Stereotypes play a crucial role in the construction of norms since they “help individuals to make sense of an increasingly complex contemporary society” (Ott & Mack, 2014). Ott and Mack (2014) define stereotypes as oversimplified and often negative generalizations about a particular social group, ignoring the diverse and nuanced characteristics that make up the group. They can be misleading and harmful in their reduction of group members to a few limited traits. They are “mental shortcuts” (Ott & Mack, 2014) and “simplistic reductions of character” (Ott & Mack, 2014). Importantly for this analysis, stereotypical representations of social groups become commonly accepted in society and media.

The concept of stigma is defined by Goffman (1963) as any type of mark that causes an individual to be ostracized or discriminated against by others. It sets them apart from others and conveys the message that they are inferior or defective in some way. This analysis will instrumentalize this concept to show how menstruation is a “stigmatized concept” (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2020) within today's German society and media.

New Blood third-wave feminism is a movement that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s through the three-way interconnectedness between the women’s health movement, consumer activism, and environmentalism (Bobel, 2010). New Blood third-wave feminists challenge the menstrual status quo. They criticize the political economy of menstruation by shedding light on the ways in which the Fem-care industry and consumer capitalism reinforce a false and hegemonic view of periods and gendered oppression (Bobel, 2010). Furthermore, they highlight the issue of environmental pollution by the mass production of single-use, non-biodegradable, hygiene products. Thus, New Blood third-wave activists combine feminism, consumer advocacy, and environmentalism to kick off a critical menstrual consciousness and advocate for change in the way menstruation is perceived and handled (Bobel, 2010). This essay will utilize this activism to analyze the online discourse of the Pinky Glove scandal.

The Pinky Glove

On the 12th of April 2021, Eugen Raimkulow and Andre Ritterswürden, the founders of the brand Pinky pitched their product on the German entrepreneur TV show Höhle der Löwen (Höhle der Löwen’ is a German TV show broadcasted on Vox where start-ups present their product to a group of investors seeking a funding deal for their business). The product, the Pinky Glove is a single-use, sealable plastic glove in pink (Figure 1). According to the founders it aims to prevent menstruators to get in contact with their period blood when removing tampons and dispose of them in the opaque and odor-proof glove. The key “benefits” of the product according to the two men; it is “hygienic” and “discreet”. In their pitch, they explain that they came up with the idea since they live in a communal house with women and feel “uncomfortable” by the smell and look of period blood in the bathroom bin. The price for the Pinky Glove is 11.96 EUR for a pack of 48. The investor Ralf Dümmel was convinced of the product's utility for menstruators and invested 30.000 euros for 20% company share (DER SPIEGEL, 2021).

Figure 1 pinky glove

The problems with the Pinky Glove

The product Pinky Glove can be critically analyzed from a New Blood third-wave feminist perspective; the interconnection of feminism, consumer activism, and environmentalism.

Starting with the perspective of the women’s health movement, it can be argued that the product stigmatizes periods and constructs them as abominations by claiming that menstruators need a glove for “hygienic” disposal. This supports the stereotype of period blood being ‘dirty’ or ‘unhygienic’ and should not be touched. Thus, their product and presentation on German TV reflect that periods are not neutral but a “stigmatized condition” (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler, 2020) within society and reinforce already existing forms of period shaming. The same applies to their argument that it is “uncomfortable” for non-menstruators to witness used menstruation products in the trash which (for the founders) explains the need for an opaque and odour-proof glove. The entrepreneur's narrative that periods should be treated as a “discreet” matter reinforces the social construction of periods as a taboo topic. It is also in line with Plan International’s (2022) survey that showed that more than 1 in 3 of the questioned boys think that periods should be kept a secret. This stresses the taboo around menstruation that is anchored in our society and supported by the Höhle der Löwen episode.

Besides the stigmatization of periods as something shameful and unhygienic, the gendered marketing of the product based on stereotypes is also problematic. The name of the brand Pinky and the use of the color pink reinforces rigid gender stereotypes and roles (Ott & Mack, 2014). Stereotypical representations are problematic since they become accepted in the media such as in the case of die Höhle der Löwen. This can lead to the disempowerment of individuals within the stereotyped group. Ott and Mack (2014) state that “stereotypes mimic reality by actually creating it”. Sometimes, people who belong to groups that are socially oppressed may internalize the stereotypes they see in the media and start behaving in ways that align with these stereotypes. In the context of die Höhle der Löwen TV show, Pinky Glove reinforces negative stigmas and stereotypes which is dangerous because menstruators risk emulating them.

On top of that, the simplistic reduction of the social group of menstruators to women is both misleading and discriminatory. Pinky glove is a product targeted towards women which can be seen in the stereotypical use of pink and the pitch of the founders that continuously use exclusionary language such as “women” instead of “menstruators”. Thus, they solely identify menstruation with women even though periods also relate to transgender or non-binary individuals. This is problematic since the use of discriminatory gendered stereotypes adds to the construction of norms that have social, cultural, and political influence especially when they are presented in the media such as pinky (Ott & Mack, 2014). Thus, it can be said that pinky reinforces a hegemonic and gender-exclusive view of periods. This is critical from a new-blood third-wave feminist perspective since they question the necessity of gender in the context of menstruation and advocate for a linguistic turn towards the term ‘menstruator’ for inclusive menstrual activism (Bobel, 2010). Additionally, the risk is again that menstruators and non-menstruators start to believe stereotypical binaries resulting in discrimination and disempowerment of stereotyped groups.

From a consumer activist perspective, Pinky Glove can also be criticized. The FemCare industry should attend to the topic of safety (Bobel, 2010), and especially a TV show on innovative products should focus on finding solutions for existing menstrual problems such as the toxic shock syndrome for instance. Instead, Pinky Glove creates and reinforces a “problem” (portraying period blood as “abnormal” and “unhygienic”) in order to sell a product (a glove so that women do not have to touch the “unhygienic” blood). One can observe that menstruation has been commodified and used for profit reasons since Pinky Gloves are 11.96 EUR for a pack of 48 in comparison to regular single-use gloves that cost around 3 EUR for 100 pieces on average. Thus, it is valid to criticize this form of consumer capitalism from a third-wave feminist perspective.

On top of that, Pinky Glove and die Höhle der Löwen can be criticized from an environmentalist perspective (Bobel, 2010). The single-use, non-biodegradable, plastic product is another wasteful menstruation product that contributes to the pollution of the environment. Especially problematic is the fact, that recycling the Pinky Glove is not possible since period products such as tampons are disposed of in the ‘rest bin’ and plastic waste in the ‘plastic bin’ in Germany.

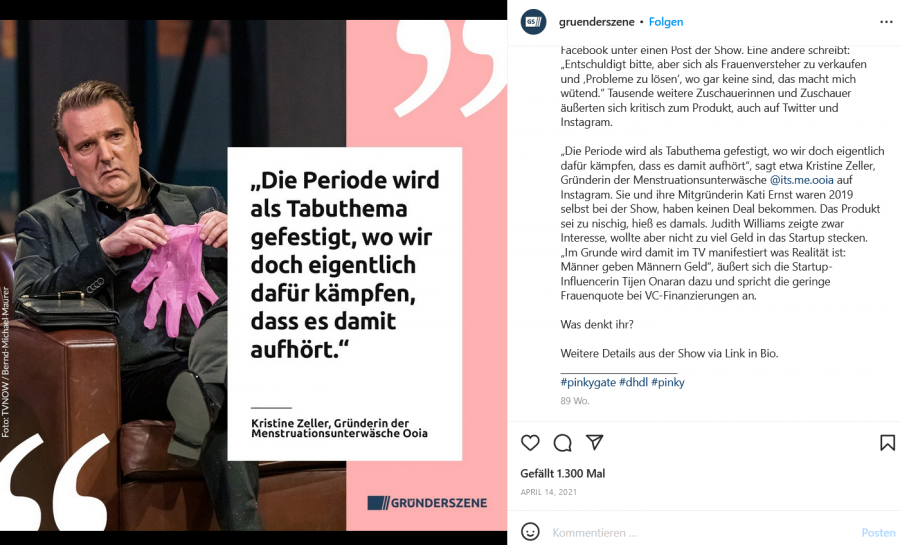

In this context, there is another controversy around die Höhle der Löwen format. In 2019, two female entrepreneurs Kati Ernst and Kristine Zeller presented their startup ‘Ooia’ to the investors. Their brand produces sustainable period panties from menstruators for menstruators. However, the environmentally friendly period product did not get a deal from any investor in contrast to Pinky Glove. This shows how systems of “gendered power imbalances” (Ott & Mack, 2014) are represented in the TV format.

#PinkyGate

Once the Pinky Glove episode has been broadcasted and the product was available on the German market, the brand Pinky and Höhle der Löwen received harsh criticism. #PinkyGate emerged as a backlash towards the product and the negative socio-cultural implications of the Pinky Glove. The contributions to the hashtag range from informational posts explaining the controversy around Pinky over menstrual art to posts trolling the product.

Figure 2 Informational commentary post on the pinky glove scandal Translation: “the period is manifested as a taboo topic, even though we should be fighting for that to stop” - Kristiane Zeller, founder of the menstruation underwear brand Ooia

The comment of the menstruation underwear brand founder Zeller underlines that the product is harmful in the sense that it reinforces stigmata and taboos and thus can have a real social impact on the way menstruators, as well as non-menstruators, see and treat periods. In the case of Pinky Glove, the product supports a negative social construction of the natural phenomenon.

In addition, the fact that the stigmatizing, discriminatory, expensive, and environmentally harmful product by non-menstruators got a deal but a sustainable and innovative product by menstruators did not, was largely criticized under #PinkyGate. As an act of solidarity, many menstrual activists bought period panties from the startup ‘Ooia’ to support the sustainable female business (Reintjes, 2021) and combat unequal gendered power.

Figure 3 Menstrual art on Instagram

The menstrual activism in the form of art in Figure 3 breaks with the convention of period stigmatization, stereotyping, and constructing it as a taboo. The sentence ‘it is normal’ in connection to the bloody fingers shows that period blood is something natural that does not have to be hidden. Likewise, it combats the stereotype that period blood is “unhygienic” and should not be touched by visually demonstrating the opposite. Therefore, the activist instrumentalizes art as a form to normalize menstruation and fight the negative constructions that Pinky Glove and the pitch on the TV show spread.

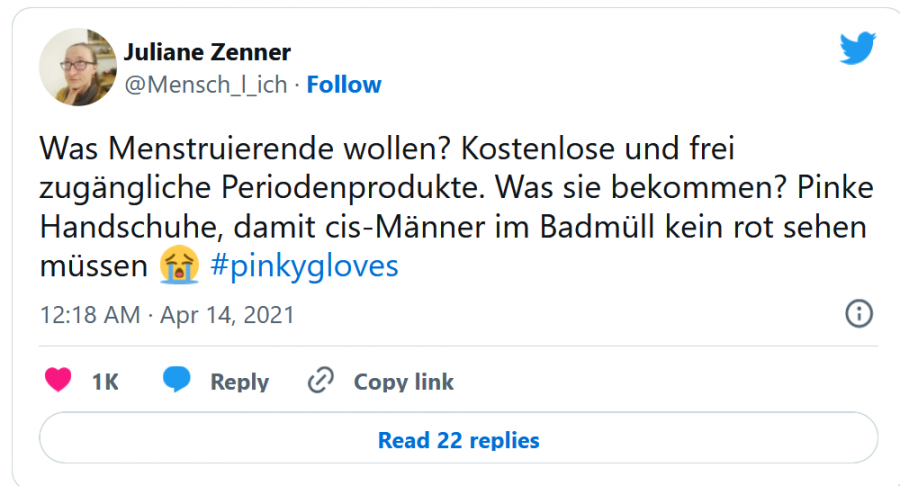

Figure 4 A Twitter post, trolling pinky glove in a socially critical manner Translation: What Menstruators want? Free and accessible period products. What they get? Pink gloves, so cis-males do not have to see red in trash bins.

The tweet shows that Pinky is not targeted toward the needs of menstruators. Instead of seeking solutions to real-life problems such as period poverty or the lack of accessibility of period products, Pinky presents a solution to a problem that does not exist. The post claims that the product and TV pitch suggest that menstruators should treat periods contingent on the male gaze and hide their natural fluids out of shame. Additionally, pinky reflects and enforces period shaming by unaffected individuals. So, the post questions the general necessity of the glove.

As a consequence of the wave of criticism that rolled over die Höhle der Löwen and the pinky founders with the hashtag activism of #pinkygate, Eugen and Andre posted an apology stating that it was not their intention to portray periods as abnormal. Furthermore, Pinky was taken off the market due to a big backlash (Condon, 2022).

So, the menstrual activists utilized the affordances of digital media to criticize a product that was discriminating, stereotyping, stigmatizing, and making menstruation appear as a taboo topic and spread visibility and menstrual awareness. Likewise, they critically questioned the general utility of the glove and adjudicated it as unnecessary.

Menstrual awareness

Finally, this article has examined the Pinky Glove scandal and the socio-cultural implications of constructed stigma, negative stereotypes, and taboos considering menstruation in contemporary German society and media. By making use of the New Blood third-wave feminist perspective it has been discovered that Pinky Glove reflects, constructs, and reinforces negative stigmata, gender-exclusive stereotypes, and taboos of menstruation within German media that menstruators and non-menstruators risk emulating. This can have a dangerous effect since this contributes to the construction of menstrual norms that have social, cultural, and political influence.

Additionally, it was shown that Pinky commodifies menstruation and uses it for profit reasons. Pinky Glove is also a non-sustainable single-use product that contributes to polluting the environment. Lastly, the article demonstrated how digital activism through critique, art, and trolling has combatted the stigmatizing and discriminating product and pitch displayed on TV and challenged the negative menstrual status quo by advocating for menstrual awareness and rights.

References

Bobel, C., Winkler, I. T., Fahs, B., Hasson, K. A., Kissling, E. A., & Roberts, T. (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies (1st ed. 2020). Palgrave Macmillan.

Condon, A. (2022, April 1). Kerry Katona Forced To Delete Pregnancy Prank Following Backlash. Tyla.

DER SPIEGEL. (2021, April 20).Gründer stampfen »Pinky Gloves« ein. DER SPIEGEL, Hamburg, Germany.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Penguin: Harmondsworth.

Johnston-Robledo, I., & Chrisler, J. C. (2020). The Menstrual Mark: Menstruation as Social Stigma. In C. Bobel (Eds.) et. al., The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. (pp. 181–199). Palgrave Macmillan.

Ott, B. L., & Mack, R. L. (2014). Critical Media Studies: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Petter, O. (2018, January 5). More than half of women feel ashamed of their periods, finds survey. The Independent.

Plan International. (2022, May 24). New survey shows ‘deep-rooted’ taboos around periods. Plan International.

Reintjes, D. (2021, April 16). Pinky Gloves Shitstorm: Gründerinnen profitieren von Kontroverse. WirtschaftsWoche.